Guidelines for Field Triage of Injured Patients Recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Guidelines for Field Triage of Injured Patients (Regional Modifications Are Permissible)

Arizona Guidelines for Field Triage of Injured Patients (Regional modifications are permissible) FIELD TRIAGE DECISION SCHEME Measure vital signs and level of consciousness Glasgow Coma Scale ≤13 Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) <90 mmHg Step One Respiratory rate <10 or >29 breaths per minute (<20 in infant aged < 1 year1), or need for ventilator support YES NO Transport to a Trauma Center2. Steps 1 and 2 attempt to identify the most seriously injured Assess anatomy of injury. patients. These patients should be transported preferentially to the highest level of care within the trauma system. • All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and extremities proximal to elbow or knee • Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g., flail chest) • Two or more proximal long-bone fractures • Crushed, de-gloved, mangled, or pulseless extremity Step Two3 • Amputation proximal to wrist or ankle • Pelvic fractures • Open or depressed skull fracture • Paralysis YES NO Transport to a Trauma Center2. Steps 1 and 2 attempt to identify the most seriously injured Assess mechanism of injury patients. These patients should be transported preferentially to the highest level of care within the and evidence of high-energy trauma system. impact. • Falls o Adults: >20 feet (one story is equal to 10 feet) 4 o Children : >10 feet or two or three times the height of the child • High-risk auto crash 5 Intrusion , including roof: >12 inches occupant site; >18 inches any site Step Three3 o o Ejection (partial or complete) from automobile o Death in same passenger compartment o Vehicle telemetry data consistent with high risk of injury 6 • Auto vs. -

Edition 2 Trauma Basics

Welcome to the Trauma Alert Education Newsletter brought to you by Beacon Trauma Services. Edition 2 Trauma Basics Trauma resuscitation is the initial stabilization and early life saving interventions provided to the trauma patient. It doesn’t mean that CPR was performed. When assessing the trauma patient it is important to recognize clues that indicate what is wrong now and what could go wrong later. Investigating the mechanism of injury is one of the most important clues to evaluate. This can be done by listening carefully to the MIST report from EMS and utilizing the 60 second time out for EMS to give report Source: https://tinyurl.com/ycjssbr3 What is wrong with me? EMS MIST 43 year old male M= unrestrained driver, while texting drove off road at 40 mph into a tree, with impact to driver’s door, 20 minute extrication time I= Deformity to left femur, pain to left chest, skin pink and warm S= B/P- 110/72, HR- 128 normal sinus, RR- 28, Spo2- 94% GCS=14 (Eyes= 4 Verbal= 4 Motor= 6) T= rigid cervical collar, IV Normal Saline at controlled rate, splint left femur What are your concerns? (think about the mechanism and the EMS report), what would you prepare prior to the patient arriving? Ten minutes after arrival in the emergency department the patient starts to have shortness of breath with stridorous sound. He is now diaphoretic and pale. B/P- 80/40, HR- 140, RR- 36 labored. Absent breath sounds on the left. What is the patients’ underlying problem?- Answer later in the newsletter Excellence in Trauma Nursing Award Awarded in May for National Trauma Month This year the nominations were very close so we chose one overall winner and two honorable mentions. -

Scheduling Operating Rooms: Achievements, Challenges and Pitfalls Samudra M, Van Riet C, Demeulemeester E, Cardoen B, Vansteenkiste N, Rademakers F

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lirias Scheduling operating rooms: achievements, challenges and pitfalls Samudra M, Van Riet C, Demeulemeester E, Cardoen B, Vansteenkiste N, Rademakers F. KBI_1608 Scheduling operating rooms: Achievements, challenges and pitfalls Michael Samudra · Carla Van Riet · Erik Demeulemeester · Brecht Cardoen · Nancy Vansteenkiste · Frank E. Rademakers Abstract In hospitals, the operating room (OR) Keywords Health care management · Surgery is a particularly expensive facility and thus effi- scheduling · Operating room planning · Review cient scheduling is imperative. This can be greatly supported by using advanced methods that are discussed in the academic literature. In order to 1 Introduction help researchers and practitioners to select new relevant articles, we classify the recent OR plan- Health care has a heavy financial burden for gov- ning and scheduling literature into tables using ernments within the European Union as well as patient type, used performance measures, deci- in the rest of the world. Additionally, while grow- sions made, OR supporting units, uncertainty, re- ing economies and newly emerging technologies search methodology and testing phase. Addition- could lead us to believe that supporting our re- ally, we identify promising practices and trends spective national health care systems might get and recognize common pitfalls when research- less expensive over time, data show that this is not ing OR scheduling. Our findings indicate, among the case. others, that it is often unclear whether an arti- For example, within the USA, the National cle mainly targets researchers and thus contributes Health Expenditure as a share of the Gross Do- advanced methods or targets practitioners and mestic Product (GDP) was 17.4% in 2013 [54]. -

Needs Assessment for New Trauma Center Development in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 2014

WHITE PAPER ON NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR NEW TRAUMA CENTER DEVELOPMENT IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA 2014 Purpose Currently new trauma center development in Pennsylvania—with limited exception—is driven by competitive financial and hospital/healthcare system imperatives. The Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation strongly recommends that going forward, new trauma center applications be based on a needs assessment process so as to optimize distribution of trauma centers in the trauma system and thereby provide optimal trauma care for the citizens of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. A guide for such a needs assessment is provided in this paper. Introduction Trauma systems have developed based on the sole precept that optimal recovery from traumatic injury is best achieved through the organization of prehospital and hospital preparedness and capability into a codified continuum of care. A codified continuum of care that is designated/accredited on a regular basis by qualified organizations such as the Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation (PTSF). It is undisputed that trauma centers in states such as Pennsylvania have significantly improved the public health for citizens of the Commonwealth. Trauma is the fifth leading cause of death in Pennsylvania. A Pa. Department of Health study demonstrated a 30% reduced chance of death for severely injured patients treated in an accredited trauma center. In 2012, 95.6% of the 40,479 trauma qualifying patients treated at a trauma center survived. Currently, there are a total of 32 trauma centers in PA as noted below. 1 Figure 1 Source: http://www.rural.palegislature.us/demographics_rural_urban_counties.html As is readily appreciated, the majority of trauma centers are in the most populated counties (Philadelphia and Allegheny) with large areas of the state seemingly having little or no ready access to organized trauma care. -

Mass/Multiple Casualty Triage

9.1 MASS/MULTIPLE CASUALTY TRIAGE PURPOSE · The goal of the mass/multiple Casualty Triage protocol is to prepare for a unified, coordinated, and immediate EMS mutual aid response by prehospital and hospital agencies to effectively expedite the emergency management of the victims of any type of Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). · Successful management of any MCI depends upon the effective cooperation, organization, and planning among health care professionals, hospital administrators and out-of-hospital EMS agencies, state and local government representatives, and individuals and/or organizations associated with disaster-related support agencies. · Adoption of Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC). DEFINITIONS Multiple Casualty Situations · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries do not exceed the ability of the provider to render care. Patients with life-threatening injuries are treated first. Mass Casualty Incidents · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries exceed the capability of the provider, and patients sustaining major injuries who have the greatest chance of survival with the least expenditure of time, equipment, supplies, and personnel are managed first. H a z GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS m Initial assessment to include the following: a t · Location of incident. & · Type of incident. M · Any hazards. C · Approximate number of victims. I · Type of assistance required. 9 . 1 COMMUNICATION · Within the scope of a Mass Casualty Incident, the EMS provider may, within the limits of their scope of practice, perform necessary ALS procedures, that under normal circumstances would require a direct physician’s order. · These procedures shall be the minimum necessary to prevent the loss of life or the critical deterioration of a patient’s condition. -

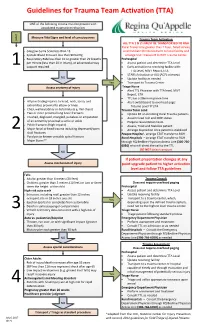

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

The Trauma Center Providing Lifesaving Care for Critically Injured Patients

A community newsletter from Antelope Valley Hospital July/August 2017 The Trauma Center Providing Lifesaving Care for Critically Injured Patients Rapid Response Mental Health Services Team Ready to Expansion on Horizon Provide Early Intervention 24/7 In this issue Growing Excellence 2 CEO Message 3 Mental Health Services Right in Your Expansion on Horizon Own Backyard 4 Rapid Response Team Ready to Provide Early Intervention 24/7 5 Hyperbaric Oxygen erapy he previous issue of HealthConnect featured an article describing the Aids in Wound Healing upcoming reopening of our outpatient surgery center through a part - nership between AV Hospital and a local surgery center. In this issue AVH Trauma Center Provides T 6 we’re announcing the expansion of our mental health services. Combined, Lifesaving Care for Critically these two initiatives signify a renewal as well as a change for both our hospital Injured Patients and the overall healthcare in our community. 9 Amazing Person e renewal, of course, is our continued commitment to ensuring that local From Tragedy Comes Sense families don’t need to travel outside the Antelope Valley to receive exceptional of Community for AVH care. at has never been truer than it is today. AV Hospital is a state-of-the-art Employee and Family medical center offering services, technologies and staffing far beyond what would normally be found in a traditional local community hospital. is includes our Hospital Highlights 10 incredible trauma center, which is also featured in this issue. What’s more is Annual Summer Blood Drive that our 450-member medical staff includes primary care physicians, internists 12 and specialists who have been trained at some of the best medical schools and programs in the world. -

History of EMS and Trauma

Ronald M. Stewart, MD Austin Trauma and Critical Care Conference June 3, 2016 No Disclosures Thank You to: . Robert Winchell, MD . Peter Fischer, MD . Susan Steinemann, MD . Dave Ciesla, MD Current status Brief history of Trauma Centers and Systems Trauma center care as a business-History The problems with “proliferation” Does trauma center level & volume matter? Current COT approach Summary “One may long, as I do, for a gentler flame, a respite, a pause for musing. But perhaps there is no other peace for the artist than what he finds in the heat of combat…Instead, let us seek the respite where it is-in the very thick of battle. For in my opinion…, it is there.” Albert Camus Robert K. Greenleaf; Larry C. Spears. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness 25th Anniversary Edition 415 ACS Verified Trauma Centers . Roughly and equal number of other TC Intense controversy in many regions . Number and type of trauma center Relevant . Cost . Stability of system . Outcomes and volume? 1913 The American College of Surgeons 1916 Earnest Codman: “A Study of Hospital Efficiency” 1917 ACS: The Hospital Standardization Program becomes the Joint Commission in 1952 1965 SSA—Medicare/Medicaid conditions of participation 6 National Academy of Sciences: Accidental Death and Disability: The neglected disease of modern society: . EMS . Emergency medicine . Trauma Surgeons . Trauma centers and systems Public Hospitals – de facto trauma centers 7 Structure Processes Outcomes (Structure, process, outcome, access, safety, costs and patient experience) 8 Set relevant high standards Build and insure the right infrastructure, leadership and processes aimed at improving quality and reducing mortality. -

Read Onlinepdf 18.98 MB

ResidentOfficial Publication of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association December 2018/January 2019 VOL 45 / ISSUE 6 Exertional Rhabdomyolysis EmBassador Travel Team Seeking the Best and Brightest EM Physicians Enjoy the flexibility to live where you want and practice where you are needed. EmBassador TRAVEL TEAM PHYSICIANS RECEIVE: Paid travel and Practice variety accommodations Concierge support Travel convenience package Regional engagements, Paid medical staff dues, equitable scheduling and licenses, certifications and no mandatory long-term applications employment commitment Exceptional Fast track to future compensation package leadership opportunities For More Information: Mansoor Khan, MD National Director, EmBassador Program 917.656.6958 | [email protected] ENVISION PHYSICIAN SERVICES OFFERS ... programs that align physicians to become leaders MANSOOR KHAN, MD, MHA, FAAEM EMERGENCY MEDICINE Why EM Residents choose Envision Physician Services ■ Professional Development and Career Advancement ■ Employment Flexibility: Full-Time, Part-Time, moonlighting and travel team. Employed and Independent Contractor options ■ Practice Variety: Coast-to-coast opportunities at well-recognized hospitals and health systems ■ Unparalleled practice support ■ Earn While You Learn Program: Provides senior residents with $2,500/month while you complete your residency For more information, contact: 877.226.6059 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL STAFF Categories EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Tommy Eales, DO Indiana University COVER STORY DEPUTY -

Program and Exhibition Guide

PROGRAM AND EXHIBITION GUIDE s January 17-21, 2015 s Phoenix Convention Center s Phoenix, Arizona, USA Download the Congress App The Root of Better Care Please visit Masimo Booth #1007 Root® is an intuitive patient monitoring and connectivity platform designed to transform patient care from the operating theater to the general ward through a powerful combination of the following high-impact innovations: > Radical-7® Instant interpretation of Masimo’s breakthrough rainbow® and SET® measurements via Root’s intuitive navigation and high-visibility, touchscreen display > MOC-9™ Flexible measurement expansion through Masimo Open Connect™ (MOC-9)—with SedLine® brain function monitoring, Phasein™ capnography, and the ability to expand with additional third-party measurements > Iris™ Built-in connectivity gateway for standalone devices such as IV pumps, ventilators, hospital beds, and other patient monitors See for yourself how Root is destined to transform patient care at www.masimo.com/root 877.4.MASIMO | www.masimo.com Root is CE Marked. © 2014 Masimo. All rights reserved. For professional use. See instructions for use for full prescribing information, including indications, contraindications, warnings, precautions and adverse events. 8655A_Ad_Root_Sedline_SCCM_2015_8.5x11.indd 1 11/12/14 4:45 PM s February 20-24, 2016 s Orange County Convention Center s Orlando, Florida, USA Inspiration at Work Connect with colleagues, experience leading-edge innovations in critical care medicine, and stretch your imagination at the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s (SCCM) 45th Critical Care Congress. Inspiration is the driving force behind a successful Congress and the spark that ignites the imagination. Participants will be certain to leave Orlando refreshed and inspired after this unparalleled event. -

Live Delivery of Neurosurgical Operating Theater Experience in Virtual Reality

Live delivery of neurosurgical operating theater experience in virtual reality Marja Salmimaa (SID Senior Member) Abstract — A system for assisting in microneurosurgical training and for delivering interactive mixed Jyrki Kimmel (SID Senior Member) reality surgical experience live was developed and experimented in hospital premises. An interactive Tero Jokela experience from the neurosurgical operating theater was presented together with associated medical Peter Eskolin content on virtual reality eyewear of remote users. Details of the stereoscopic 360-degree capture, surgery imaging equipment, signal delivery, and display systems are presented, and the presence Toni Järvenpää (SID Member) Petri Piippo experience and the visual quality questionnaire results are discussed. The users reported positive scores Kiti Müller on the questionnaire on topics related to the user experience achieved in the trial. Jarno Satopää Keywords — Virtual reality, 360-degree camera, stereoscopic VR, neurosurgery. DOI # 10.1002/jsid.636 1 Introduction cases delivering a sufficient quality, VR experience is important yet challenging. In general, perceptual dimensions Virtual reality (VR) imaging systems have been developed in affecting the quality of experience can be categorized into the last few years with great professional and consumer primary dimensions such as picture quality, depth quality, interest.1 These capture devices have either two or a few and visual comfort, and into additional ones, which include, more camera modules, providing only a monoscopic view, or for example, naturalness and sense of presence.5 for instance eight or more cameras to image the surrounding VR systems as such introduce various features potentially environment in stereoscopic, three-dimensional (3-D) affecting the visual experience and the perceived quality of fashion.