An Overview of Microscopic and Macroscopic Traffic Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fibre Reinforced Plastic Concepts for Structural Chassis Parts

Transport Research Arena 2014, Paris Fibre Reinforced Plastic Concepts for Structural Chassis Parts Oliver Deisser*, Prof. Dr. Horst E. Friedrich, Gundolf Kopp German Aerospace Center / Institute of Vehicle Concepts Pfaffenwaldring 38-40, 70569 Stuttgart Abstract Fibre reinforced plastics (FRP) have a high potential for reducing masses of automotive parts, but are seldom used for structural parts in the chassis. If the whole chassis concept is adapted to the new material, then a high weight saving potential can be gained and new body concepts can result. DLR Institute of Vehicle Concepts designed and dimensioned a highly stressed structural part in FRP. A topology optimisation of a defined working space with the estimated loads was performed. The results were analysed and fibre reinforced part concepts derived, detailed and evaluated. Especially by the use of the new FRP material system in the chassis area, a weight saving of more than 30% compared to the steel reference was realised. With the help of those concepts it is shown, that there is also a great weight saving potential in the field of chassis design, if the design fits with the material properties. The existing concepts still have to be detailed further, simulated and validated to gain the full lightweight potential. Keywords: Fibre Reinforced Plastics; Chassis Design; Lightweight Design Concepts; Finite Element Simulation; FEM. Résumé Plastiques renforcés de fibres (PRF) ont un fort potentiel de réduction des masses de pièces automobiles, mais sont rarement utilisés pour des pièces de structure du châssis. Si le concept de châssis est adapté au nouveau matériel, un potentiel élevé d'épargne de poids peut être acquis et de nouveaux concepts de construction peuvent en résulter. -

Autonomous Vehicle Engineering Guide Top Breakthroughs & Resources in Autonomous and Connected Vehicles AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE ENGINEERING GUIDE

EBOOK Autonomous Vehicle Engineering Guide Top Breakthroughs & Resources in Autonomous and Connected Vehicles AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE ENGINEERING GUIDE 5 Contents SENSORS 7 3 For Lidar, MEMs the Word 5 New Performance Metrics for Lidar 7 Detecting Pedestrians SOFTWARE AND AI/MACHINE LEARNING 12 9 Software Building Blocks for AV Systems 12 New Mobility’s Mega Mappers 15 Can Autonomous Vehicles Make the Right ‘Decision?’ 19 CONNECTED VEHICLE ELECTRONICS 17 Expanding the Role of FPGAs 19 Electronic Architectures Get Smart ABOUT ON THE COVER Autonomous Vehicle Engineering covers the In the article Software Building Blocks constantly-evolving field of autonomous and for AV Systems, Sebastian Klaas explores connected vehicles from end to end — covering how Elektrobit's unique software frame- key technologies and applications including work is designed to smooth develop- sensor fusion, artificial intelligence, smart cities, ment of automated driving functions. and much more. This Autonomous Vehicle Automated valet parking is an example Engineering Ebook is a compilation of some of of a practical application of the software the magazine's top feature articles from thought framework. Read more on page 9. leaders, and is your guide to designing the next (Image: Elektrobit) generation of vehicles. 2 AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE ENGINEERING SAE EBOOK SENSORS For Lidar, MEMS the Word by Charles Chung, Ph.D. Tiny gimballed mirrors on chips are being developed that could improve the form factor and cost of automotive lidar. As automakers and their technology partners develop lidar sensors to enable SAE Level 4-5 autonomous driving, some systems designers believe MEMS micromirrors have the potential to reduce overall size and cost—two major hurdles to widespread lidar adoption. -

The Electric Vehicle Evolution

THE ELECTRIC VEHICLE EVOLUTION Electric vehicles are a growing market for new car purchases with more and more people making the switch from the gas station to an electrical outlet to fuel their vehicles. Electric vehicles use electricity as their primary fuel or use electricity along with a conventional engine to improve efficiency (plug-in hybrid vehicles). Drivers are purchasing the vehicles for all kinds of reasons. Many decide to buy when they hear about the savings. Drivers see around $700 in savings a year in gasoline expenses when they drive an average of 12,000 miles. They also can realize substantial tax credits that encourage low-emission and emissions-free driving. Additional benefits include environmental improvements because of reduced vehicle emissions, energy independence by way of using locally-generated electricity and high quality driving performance. With the influx of electric vehicles comes a need for charging infrastructure. Throughout the country, businesses, governments and utilities have been installing electric vehicle charging stations. According to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center, there are over tens of thousands of vehicle charging outlets across the country. This trend toward electric vehicles is expected to continue, especially with the billions of dollars that auto manufacturers are investing in these new vehicles. The list of manufacturer support is long with almost every large automobile manufacturer currently developing or selling an electric vehicle. But how and why did this all get started? Let’s step back and take a look at the history of electric transportation. 1 THE ELECTRIC VEHICLE EVOLUTION EARLY SUCCESS Electric vehicles actually have their origin in the 1800s. -

Assignment of New Vehicle Identification Number Application

APPLICATION AND ASSIGNMENT OF NEW VEHICLE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER SECRETARY OF STATE BUREAU OF MOTOR VEHICLES $33.00 FEE REQUIRED DIVISION OF TITLE SERVICES Make Checks payable to: SECRETARY OF STATE OWNERS LEGAL NAME DATE OF BIRTH CURRENT STREET ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP APPLICATION DATE HOME PHONE WORK PHONE YEAR MAKE MODEL BODY TYPE MISSING VEHICLE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER – IF KNOWN EXACT CURRENT LOCATION OF VEHICLE –STREET ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP NET WEIGHT - IF TRAILER CC - IF MOTORCYCLE ENGINE NUMBER – IF MOTORCYCLE Subject to inspection by a Bureau of Motor Vehicle detective, the undersigned makes this application for a new vehicle identification number, to be assigned permanently to the vehicle listed above. The applicant also agrees to submit an application for a title certificate (MVT-2) to bear the new number, if this vehicle is 1995 or newer and subject to Maine title law. I certify that I am the owner of the vehicle described above and that said Vehicle requires a Vehicle Identification Number because (CHECK ONE REASON BELOW): ❑ Number was destroyed or obliterated ❑ Homemade vehicle ❑ Other (Explain) _________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ OWNER’S SIGNATURE IMPORTANT – PLEASE ALSO READ AND COMPLETE THE BACK OF THIS FORM FOR BMV USE ONLY SPECIAL MOTOR VEHICLE CERTIFICATION FOR BMV USE ONLY This permanent Vehicle Identification Number has been properly affixed to the vehicle described above M E INSPECTOR’S NAME (PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY) INSPECTOR’S SIGNATURE DATE NUMBER AFFIXED ODOMETER READING COMMENTS 101 Hospital Street, #29 State House Station, Augusta, ME 04333-0029 Tel. (207) 624-9000 ext. 52138 Fax: (207) 624-9239 TTY Users call Maine Relay 711 MVT-6 Rev. -

History of Intelligent Transportation Systems Publication Number

HISTORY OF INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS WWW.ITS.DOT.GOV/INDEX.HTM PUBLICATION NUMBER WWW.ITS.DOT.GOV/INDEX.HTM PUBLICATION NUMBER: FHWA-JPO-16-329 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS JOINT PROGRAM OFFICE B U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS JOINT PROGRAM OFFICE Produced by Booz Allen Hamilton U.S. Department of Transportation Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The U.S. Government is not endorsing any manufacturers, products, or services cited herein and any trade name that may appear in the work has been included only because it is essential to the contents of the work. C U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS JOINT PROGRAM OFFICE Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-JPO-16-329 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date History of Intelligent Transportation Systems May 2016 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Ashley Auer, Shelley Feese, and Stephen Lockwood 9. Performing Organization Name And Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Booz Allen Hamilton 8283 Greensboro Drive 11. Contract or Grant No. McLean, VA 22102 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office 1200 New Jersey Ave SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 15. -

The Autonomous Vehicle Revolution Fostering Innovation with Smart Regulation

THE AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE REVOLUTION FOSTERING INNOVATION WITH SMART REGULATION MARCH 2017 The Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress, founded in 1965, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan 501(c)(3) organization. The Center’s mission is to utilize the lessons of history to address the challenges of today; serve as a strategic honest broker for discussions with leaders from government, the private sector, and the policy community; and to educate the next generation of leaders through the Presidential and International Fellows Program. THE AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE REVOLUTION: FOSTERING INNOVATION WITH SMART REGULATION March 2017 Copyright © 2017 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRESIDENCY & CONGRESS All rights reserved. No portion of this report may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Published in the United States of America. Selected Cover Image Credits: Silver Blue, Flickr; Jennifer Morrow, Flickr; Wikimedia Commons 601 Thirteenth Street, NW – Suite 1050N Washington, D.C. 20005 Phone: 202-872-9800 Fax: 202-872-9811 www.thePresidency.org Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved THE AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE REVOLUTION: FOSTERING INNOVATION WITH SMART REGULATION PROJECT DIRECTORS: MAXMILLIAN ANGERHOLZER III DAN MAHAFFEE LEAD RESEARCHER: MADELINE VALE PROJECT ADVISORS: JAMES KITFIELD HURST RENNER WASHINGTON, D.C. MARCH 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 REPORT FINDINGS ............................................................................................................. -

Autonomous Vehicle Technology: a Guide for Policymakers

Autonomous Vehicle Technology A Guide for Policymakers James M. Anderson, Nidhi Kalra, Karlyn D. Stanley, Paul Sorensen, Constantine Samaras, Oluwatobi A. Oluwatola C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr443-2 This revised edition incorporates minor editorial changes. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-8398-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Advertisement from 1957 for “America’s Independent Electric Light and Power Companies” (art by H. Miller). Text with original: “ELECTRICITY MAY BE THE DRIVER. One day your car may speed along an electric super-highway, its speed and steering automatically controlled by electronic devices embedded in the road. Highways will be made safe—by electricity! No traffic jams…no collisions…no driver fatigue.” Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. -

2Nd-Generation SJ-MOSFET for Automotive Applications

2nd-Generation SJ-MOSFET for Automotive Applications “Super J MOS S2A Series” TABIRA, Keisuke * NIIMURA, Yasushi * MINAZAWA, Hiroshi * ABSTRACT There has been increasing demand for smaller power conversion equipment and better fuel efficiency in eco- friendly vehicles such as hybrid electric vehicles. Accordingly, power MOSFET products are being required to be compact, low loss and low noise. Fuji Electric has developed and launched the “Super J MOS S1A Series,” a product for automotive applications that adopt a superjunction structure characterized by their low on-state resistance and low switching loss. More recently, Fuji Electric has developed the 2nd-Generation SJ-MOSFET for automotive applica- tions “Super J MOS S1A Series,” which reduces conduction loss while improving the trade-off between switching loss and jumping voltage during turn-off switching. The use of this product contributes to size reduction and enhanced ef- ficiency of the power conversion equipment for automotive applications. 1. Introduction turn-off switching. Recently, in the automotive market, eco-friendly 2. Design Concept vehicles represented by hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (P-HEVs) and Figure 1 shows a breakdown of the loss generated electric vehicles (EVs) have been attracting atten- in a power MOSFET in a power factor correction (PFC) issue: Power Semiconductors Contributing in Energy Management issue: Power Semiconductors Contributing in Energy tion as environmental regulations become increasingly circuit of a charger for automotive applications. The stringent and users’ environmental awareness rises. generated loss of a power MOSFET can be roughly Efficient use of the electric power of the batteries classified into conduction loss Pon and switching loss mounted on these types of vehicles directly leads to an consisting of turn-on loss Pton and turn-off loss Ptoff. -

Electric Vehicles As Distributed Energy Resources

ELECTRIC VEHICLES AS DISTRIBUTED ENERGY RESOURCES BY GARRETT FITZGERALD, CHRIS NELDER, AND JAMES NEWCOMB O Y M UN ARBON K T C C A I O N R I W N E A M STIT U T R R O O AUTHORS & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AUTHORS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Garrett Fitzgerald, Chris Nelder, and James Newcomb The authors thank the following individuals and e-Lab * Authors listed alphabetically. All authors are from member organizations for offering their insights and Rocky Mountain Institute unless otherwise noted. perspectives on this work, which does not necessarily reflect their views. ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTORS Jim Lazar, Regulatory Assistance Project Rich Sedano, Regulatory Assistance Project Riley Allen, Regulatory Assistance Project Sarah Keay-Bright, Regulatory Assistance Project Jim Avery, San Diego Gas & Electric CONTACTS Greg Haddow, San Diego Gas & Electric Chris Nelder ([email protected]) San Diego Gas & Electric Load Analysis Group James Newcomb ([email protected]) Noel Crisostomo, California Public Utilities Commission Jonathan Walker, Rocky Mountain Institute SUGGESTED CITATION Chris Nelder, James Newcomb, and Garrett Fitzgerald, The authors also thank the following additional Electric Vehicles as Distributed Energy Resources individuals and organizations for offering their insights (Rocky Mountain Institute, 2016), and perspectives on this work: http://www.rmi.org/pdf_evs_as_DERs. Joel R. Pointon, JRP Charge Joyce McLaren, National Renewable Energy Laboratory DISCLAIMER e-Lab is a joint collaboration, convened by RMI, with participationfrom stakeholders across the electricity Editorial Director: Cindie Baker industry. e-Lab is not a consensus organization, and Editor: David Labrador the views expressed in this document are not intended Art Director: Romy Purshouse to represent those of any individual e-Lab member or Images courtesy of iStock unless otherwise noted. -

Design of an Integrated Circuit for Electrical Vehicle with Multiple Outputs

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 118 No. 20 2018, 4887-4901 ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.ijpam.eu Special Issue ijpam.eu DESIGN OF AN INTEGRATED CIRCUIT FOR ELECTRICAL VEHICLE WITH MULTIPLE OUTPUTS Ms.K. PRIYADHARSINI ,M.E., 1 Ms. A. LITTLE JUDY, M.E.,2 Mr. K. MOHAN, 3 4 M.E., Ms. R. DIVYA, M.E., 1Assistant Professor, Sri Krishna College of Engineering and technology Email id: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract: The vehicles spreading unit (OLPU) to improve the power system are used on the electric density through the circuit vehicles on the battery vehicles in integration. The proposed system has hybrid electric vehicles. The battery advantages in the reduction of inverters on the converters motor on principal components of the power the core technologies .the attempt to stage as well as high power density improve battery on the low voltage through a shared heat sink and level DC-DC to converter. The AC TO mounting space. In addition the DC conversion are modified by the shared circuit reduces the cost by isolated transformer. The DC-DC converter are maintained by the eliminating the automotive high- isolated technology. The grid battery power cable technology are maintained by HVBs as an input source and supply power that is necessary for the power flow to the electronic devices and low between the OBC and the LDC in the voltage battery (LVB) in the vehicle. conventional system. Moreover, the This system proposes an OBC-LDC OLPU brings the structures and integrated power advantages of the OBC and LDC in conventional (x EVs) . -

2008 Advanced Vehicle Technology Analysis and Evaluation Activities

annual progress report 2008V EHICLE T ECHNOLOGIES P ROGRAM ADVANCED VEHICLE TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION ACTIVITIES AND HEAVY VEHICLE SYSTEMS OPTIMIZATION PROGRAM A Strong Energy Portfolio for a Strong America Energy efficiency and clean, renewable energy will mean a stronger economy, a cleaner environment, and greater energy independence for America. Working with a wide array of state, community, industry, and university partners, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy invests in a diverse portfolio of energy technologies. For more information contact: EERE Information Center 1-877-EERE-INF (1-877-337-3463) www.eere.energy.gov U.S. Department of Energy Vehicle Technologies Program 1000 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20585-0121 FY 2008 Annual Progress Report for Advanced Vehicle Technology Analysis and Evaluation Activities and Heavy Vehicle Systems Optimization Program Submitted to: U.S. Department of Energy Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Vehicle Technologies Program Advanced Vehicle Technology Analysis and Evaluation Lee Slezak, Technology Manager FY 2008 Annual Report AVTAE Activities & HVSO Program ii AVTAE Activities & HVSO Program FY 2008 Annual Report CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................1 II. MODELING AND SIMULATION....................................................................................................9 A. PSAT Model Validation ...............................................................................................................9 -

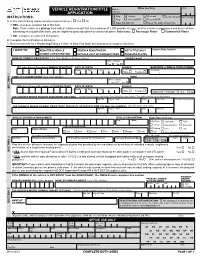

Vehicle Registration/Title Application – MV-82.1

Office Use Only Class VEHICLE REGISTRATION/TITLE Batch APPLICATION File No. o Orig o Activity o Renewal o INSTRUCTIONS: Lease Buyout Three of Name o Dup o Activity W/RR o Renew W/RR A. Is this vehicle being registered only for personal use? o Yes o No o Sales Tax with Title o Sales Tax Only without Title If YES - Complete sections 1-4 of this form. Note: If this vehicle is a pick-up truck with an unladen weight that is a maximum of 6,000 pounds, is never used for commercial purposes and does not have advertising on any part of the truck, you are eligible for passenger plates or commercial plates. Select one: o Passenger Plates o Commercial Plates If NO - Complete sections 1-5 of this form. B. Complete the Certification in Section 6. C. Refer to form MV-82.1 Registering/Titling a Vehicle in New York State for information to complete this form. I WANT TO: REGISTER A VEHICLE RENEW A REGISTRATION GET A TITLE ONLY Current Plate Number CHANGE A REGISTRATION REPLACE LOST OR DAMAGED ITEMS TRANSFER PLATES NAME OF PRIMARY REGISTRANT (Last, First, Middle or Business Name) FORMER NAME (If name was changed you must present proof) Name Change Yes o No o NYS driver license ID number of PRIMARY REGISTRANT DATE OF BIRTH GENDER TELEPHONE or MOBILE PHONE NUMBER Month Day Year Area Code o o Male Female ( ) NAME OF CO-REGISTRANT (Last, First, Middle) EMAIL Name Change Yes o No o NYS driver license ID number of CO-REGISTRANT DATE OF BIRTH GENDER SECTION 1 Month Day Year Male o Female o ADDRESS CHANGE? o YES o NO THE ADDRESS WHERE PRIMARY REGISTRANT GETS MAIL (Include Street Number and Name, Rural Delivery or box number.