Unit 20 Socialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

SEWER SYNDICALISM: WORKER SELF- MANAGEMENT in PUBLIC SERVICES Eric M

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NVJ\14-2\NVJ208.txt unknown Seq: 1 30-APR-14 10:47 SEWER SYNDICALISM: WORKER SELF- MANAGEMENT IN PUBLIC SERVICES Eric M. Fink* Staat ist ein Verh¨altnis, ist eine Beziehung zwischen den Menschen, ist eine Art, wie die Menschen sich zu einander verhalten; und man zerst¨ort ihn, indem man andere Beziehungen eingeht, indem man sich anders zu einander verh¨alt.1 I. INTRODUCTION In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, municipal govern- ments in various US cities assumed responsibility for utilities and other ser- vices that previously had been privately operated. In the late twentieth century, prompted by fiscal crisis and encouraged by neo-liberal ideology, governments embraced the concept of “privatization,” shifting management and control over public services2 to private entities. Despite disagreements over the merits of privatization, both proponents and opponents accept the premise of a fundamental distinction between the “public” and “private” sectors, and between “state” and “market” institutions. A more skeptical view questions the analytical soundness and practical signifi- cance of these dichotomies. In this view, “privatization” is best understood as a rhetorical strategy, part of a broader neo-liberal ideology that relies on putative antinomies of “public” v. “private” and “state” v. “market” to obscure and rein- force social and economic power relations. While “privatization” may be an ideological definition of the situation, for public service workers the difference between employment in the “public” and “private” sectors can be real in its consequences3 for job security, compensa- * Associate Professor of Law, Elon University School of Law, Greensboro, North Carolina. -

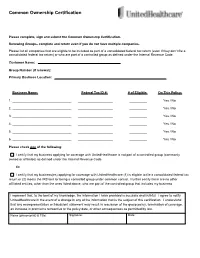

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Notes 335 Bibliography 387 Index 413

CONTENTS PREFACE IX ONE: THE AMBIGUOUS LEGACY 3 The Crisis of Classical Marxism 6 The Crisis in Italy 20 Italian Revolutionary Syndicalism 22 TWO: THE FIRST REVOLUTIONARY SOCIALIST HERESY 32 The Evolution of Syndicalism 32 Syndicalism and the Nature of Man 34 Syndicalism and Social Psychology 37 Syndicalism and the Social and Political Function of Myth 43 Elitism 50 Syndicalism and Industrial Development 58 THREE: THE FIRST NATIONAL SOCIALISM 64 Revolutionary Syndicalism: Marxism and the Problems of National Interests 64 Syndicalism and Proletarian Nationalism 71 Revolutionary Syndicalism, War, and Moral Philosophy 73 Syndicalism, Nationalism, and Economic Development 83 National Syndicalism and Lenin's Bolshevism 91 FOUR: THE PROGRAM OF FASCISM 96 The Fascism of San Sepolcro 101 Syndicalism, Nationalism, and Fascism 103 FascismandIdeology 112 Fascism and Bolshevism 121 FIVE: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF FASCISM 127 Alfredo Rocco, Nationalism, and the Economic Policy of Fascism 133 Economic Policy from 1922 until the Great Depression 140 Fascist Economic Policy after the Great Depression 153 The Political Economy of Fascism and the Revolutionary Socialist Tradition 162 SIX: THE LABOR POLICY OF FASCISM 172 The Origins of Fascist Syndicalism 172 The Rise of Fascist Syndicalism 183 The Evolution of Fascist Syndicalism 190 The Functions of Fascist Syndicalism 196 The Labor Policy of Fascism and Revolutionary Marxism 206 SEVEN: THE ORCHESTRATION OF CONSENSUS 214 Syndicalism, Fascism, and the Psychology of the Masses 215 The Rationale of Orchestrated -

The Case of Bernstein and Engels

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Probabilism and determinism in political economy: the case of Bernstein and Engels Wells, Julian The Open University 3 February 1998 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/55325/ MPRA Paper No. 55325, posted 22 Jan 2020 09:07 UTC Probabilism and determinism in political economy The case of Bernstein and Engels Julian Wells The Open University I: Introduction Eduard Bernstein’s proposals for revising marxist theory Rather, it is to examine the intellectual sources of his burst like a thunderclap on the late 19th century workers’ error, and in particular to examine Bernstein’s views on movement, and in particular on the German social the determinism which he maintained was a central feature democracy. Here was the militant who had suffered 20 of the historical materialist method. This is important, years of exile, whose editorship of the party newspaper had because—as I claimed in passing in a previous IWGVT made it such a powerful weapon, the acquaintance of Marx paper (Wells 1997) but did not substantiate—there is a and the friend and literary executor of Engels, saying in pervasive atmosphere of determinism in the thought of terms that their scientific method was so fatally flawed that many marxists, which is, however, unjustified by anything it should be fundamentally recast. to be found in the works of Marx and Engels. Not only that, but Marx’s forecasts about the The paper will first review Bernstein’s critique of Marx development of capitalism, made on the basis of this and Engels, and suggest that his misunderstanding is not method, were not only untenable but had already been simply attributable to any personal scholarly exposed by events. -

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit To cite this version: Fabien Tarrit. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership. Buletinul Stiintific Academia de Studii Economice di Bucuresti, Editura A.S.E, 2008, 9 (1), pp.347-355. hal-02021060 HAL Id: hal-02021060 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02021060 Submitted on 15 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership TARRIT Fabien Lecturer in Economics OMI-LAME Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne France Abstract: This article intends to demonstrate that the concept of self-ownership does not necessarily imply a justification of inequalities of condition and a vindication of capitalism, which is traditionally the case. We present the reasons of such an association, and then we specify that the concept of self-ownership as a tool in political philosophy can be used for condemning the capitalist exploitation. Keywords: Self-ownership, libertarianism, capitalism, exploitation JEL : A13, B49, B51 2 The issue of individual freedom as a stake went through the philosophical debate since the Greek antiquity. We deal with that issue through the concept of self-ownership. -

Libertarian Socialism

Libertarian Socialism Politics in Black and Red Editors: Alex Prichard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta, and David Berry The history of anarchist-Marxist relations is usually told as a history of faction- alism and division. These essays, based on original research and written espe- cially for this collection, reveal some of the enduring sores in the revolutionary socialist movement in order to explore the important, too often neglected left- libertarian currents that have thrived in revolutionary socialist movements. By turns, the collection interrogates the theoretical boundaries between Marxism and anarchism and the process of their formation, the overlaps and creative ten- sions that shaped left-libertarian theory and practice, and the stumbling blocks to movement cooperation. Bringing together specialists working from a range of political perspectives, the book charts a history of radical twentieth-century socialism, and opens new vistas for research in the twenty-first. Contributors examine the political and social thought of a number of leading socialists— Marx, Morris, Sorel, Gramsci, Guérin, C.L.R. James, Hardt and Negri—and key movements including the Situationist International, Socialisme ou Barbarie and Council Communism. Analysis of activism in the UK, Australasia, and the U.S. serves as the prism to discuss syndicalism, carnival anarchism, and the anarchistic currents in the U.S. civil rights movement. Contributors include Paul Blackledge, Lewis H. Mates, Renzo Llorente, Carl SUBJECT CATEGORY Levy, Christian Høgsbjerg, Andrew Cornell, Benoît Challand, Jean-Christophe Politics-Anarchism/Politics-Socialism Angaut, Toby Boraman, and David Bates. PRICE ABOUT THE EDITORS $26.95 Alex Prichard is senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of Exeter. -

Eduard Bernstein Speaks to the Fabians: a Turning-Point in Social Democratic Thought?

DOCUMENTS H. Kendall Rogers EDUARD BERNSTEIN SPEAKS TO THE FABIANS: A TURNING-POINT IN SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC THOUGHT? Of Eduard Bernstein's many writings surely few were as significant in the early development of revisionism as his speech to the London Fabian Society on January 29, 1897. In an October 1898 letter to August Bebel, Bernstein described the gradual metamorphosis that had led to his heterodox views. Until October 1896 he had sought to "stretch" Marxist theory to conform to social-democratic practice; finally he realized this was impossible. Bezeichnender od. auch begreiflicher Weise, wurde mir das Unmogliche dieses Vorhabens erst vollig klar, als ich vor anderthalb Jahren, im Verein der Fabier einen Vortrag darilber hielt, "Was Marx wirklich lehrte". Ich habe das Manuskript des Vortrages noch, es ist ein abschreckendes Beispiel wohlmeinenden "Rettungsversuchs". Ich wollte Marx retten, wollte zeigen, daB alles so gekommen was er gesagt, und, daB alles, was nicht so gekom- men, auch von ihm gesagt wurde. Aber als das Kunststiick fertig war, als ich den Vortrag vorlas, da zuckte es mir durch den Kopf: Du thust Marx Unrecht, das ist nicht Marx, was Du vorfuhrst. Und ein paar harmlose Fragen, die mir ein scharfsinniger Fabianer Hubert Bland nach dem Vor- trag stellte und die ich noch in der alten Manier beantwortete, gaben mir den Rest. Im Sullen sagte ich mir: so geht das nicht weiter.1 For some historians Bernstein's Fabian lecture was the point where he turned decisively against Marxism. For those who date Bernstein's repudiation of Marx from Engels's death, the address at least marked the point where Bernstein realized how thoroughly he had already broken with Marxist orthodoxy.2 And for all students of pre-war social-democratic 1 Bernstein to Bebel, October 20, 1898, in: Victor Adler, Briefwechsel mit August Bebel und Karl Kautsky, ed. -

Common Ownership Community “COC”

So, are you a good neighbor? Do you know your association’s Board of Directors? Do you … ? Are you aware of when and where your association • Pay your assessments on time? meets? Have you reviewed your association’s • Abide by the rules, regulations and bylaws? bylaws? • Attend Board of Directors meetings? • Vote in elections and on critical matters? How to be a Consider getting involved. Get engaged and be aware! For additional information on Common GOOD NEIGHBOR in a Ownership Communities, please contact the • Browse your Association’s newsletter and email following: blasts, so that you have an idea of what’s going on and, so that you’ll be able to participate Office of Community Relations Common if there’s something you strongly agree or Ownership Communities disagree with. Phone: 301-952-4729 http://www.princegeorgescountymd.gov/921/ • Attend Association meetings. This will help Common-Ownership-Communities you find out what’s going on in your community and will help you become informed. You’ll FHA Resource Center have a greater influence over what happens https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/ in your building or neighborhood and it’s an sfh/fharesourcectr opportunity to meet your neighbors. Office of the Attorney General Consumer At the end of the day, there is a difference between Protection Division living in a community and being a part of that Phone: 877-261-8807 particular community. While being part of an http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/ Common Association can be a bit of extra work, it’s worth CPD%20Documents/Tips-Publications/ putting some effort into being a good member. -

Variants of Corporatist Governance: Differences in the Korean and Japanese Approaches in Dealing with Labor

Variants of Corporatist Governance: Differences in the Korean and Japanese Approaches in Dealing with Labor By Taekyoon Kim Many scholars have highlighted Japan and South Korea (hereafter, Korea) as distinctive models of the “developmental state”, which can share common features in terms of the condensed economic development.1 The close strategic relationship between the bureaucratic government and big businesses has been often cited as one of the many similarities in which the two countries pursued rapid economic growth.2 Another trend in comparing the modern economies of Korea and Japan highlights the state’s embedded autonomy in directing industrial transformation.3 Overall, scholarly interest in the comparison of the two Asian countries’ modernization has been, hitherto, limited to economic and political development, rather than focusing on social relations underlying the political economy of post-war development. Indeed, a comparative analysis of the similarities and differences in the his- torical patterns of the emergence of “systems of interest intermediation” in dealing with labor in Japan and Korea is a relatively unexploited topic.4 There have only been a few attempts made at comparing the national bargaining arrangements among major interest groups and governments. Although some pioneering Japanese works introduce a corporatist account for its post-war labor relations5 and a historical analysis of negotiation characteristics of social contracts6, they all simply classify the Japanese case as an anomaly with the emphasis on the state’s deliberate management of weak labor forces. Like- wise, the existing literature related to Korea’s labor politics and civil society tends to emphasize the uniqueness embedded in its social and industrial relations – the confrontation between “the strong state and the contentious society.”7 Thus, the dearth of comparative perspective in this area results in Taekyoon Kim received his D.Phil at the University of Oxford.