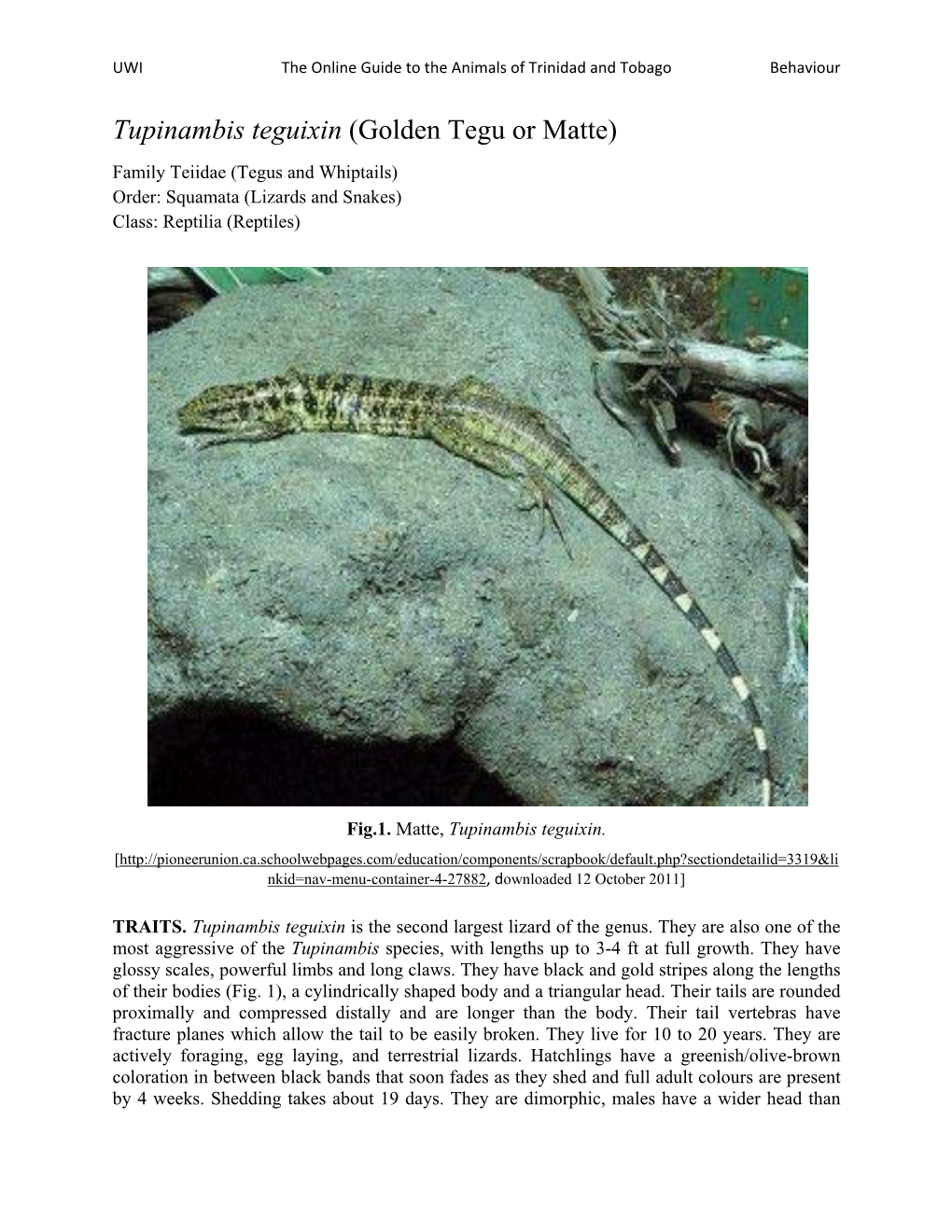

Tupinambis Teguixin (Golden Tegu Or Matte)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile-Like Physiology in Early Jurassic Stem-Mammals

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title: Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals Authors: Elis Newham1*, Pamela G. Gill2,3*, Philippa Brewer3, Michael J. Benton2, Vincent Fernandez4,5, Neil J. Gostling6, David Haberthür7, Jukka Jernvall8, Tuomas Kankanpää9, Aki 5 Kallonen10, Charles Navarro2, Alexandra Pacureanu5, Berit Zeller-Plumhoff11, Kelly Richards12, Kate Robson-Brown13, Philipp Schneider14, Heikki Suhonen10, Paul Tafforeau5, Katherine Williams14, & Ian J. Corfe8*. Affiliations: 10 1School of Physiology, Pharmacology & Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 2School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 3Earth Science Department, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 4Core Research Laboratories, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 5European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. 15 6School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 7Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 8Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 9Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 10Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 20 11Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Zentrum für Material-und Küstenforschung GmbH Germany. 12Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford, OX1 3PW, UK. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 13Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 14Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Overwintering in Tegu Lizards

Overwintering in Tegu Lizards DENIS V. ANDRADE,1 COLIN SANDERS,1, 2 WILLIAM K. MILSOM,2 AND AUGUSTO S. ABE1 1 Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, SP, Brasil 2 Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada Abstract. The tegu, Tupinambis merianae, is a large South American teiid lizard, which is active only during part of the year (hot summer months), spending the cold winter months sheltered in burrows in the ground. This pattern of activity is accompanied by seasonal changes in preferred body temperature, metabolism, and cardiorespiratory function. In the summer months these changes are quite large, but during dormancy, the circadian changes in body temperature observed during the active season are abandoned and the tegus stay in the burrow and al- low body temperature to conform to the ambient thermal profile of the shelter. Metabolism is significantly depressed during dormancy and relatively insensitive to alterations in body temperature. As metabolism is lowered, ventilation, gas exchange, and heart rate are adjusted to match the level of metabolic demand, with concomitant changes in blood gases, blood oxygen transport capacity, and acid-base equilibrium. Seasonality and the Tegu Life Cycle As with any other ectothermic organism, the tegu lizard, Tupinambis merianae, depends on external heat sources to regulate body temperature. Although this type of thermoregulatory strategy conserves energy by avoiding the use of me- tabolism for heat production (Pough, 1983), it requires that the animal inhabit a suitable thermal environment to sustain activity. When the environment does not provide the range of temperatures that enables the animal to be active year round, many species of ectothermic vertebrates become seasonally inactive (Gregory, 1982). -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 26(2):121–122 • AUG 2019 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Mating. Chasing Bullsnakes ( Pituophisof catenifer Argentine sayi) in Wisconsin: Black-and-white On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared HistoryTegus of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis(Salvator) and Humans on Grenada: merianae ) A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 inRESEARCH Miami-Dade ARTICLES County, Florida, USA . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (AnolisJenna equestris M.) in FloridaCole, Cassidy Klovanish, and Frank J. Mazzotti .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 . More Than Mammals ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Fitzgerald, LA, JM Chani, and OE Donadio

Fitzgerald, L.A., J.M. Chani, and O.E. Donadio. 1991. Tupinambis lizards in Argentina: Implementing management of a traditionally exploited resource. Pages 303-316 in Robinson, J. and K. Redford, eds. “Neotropical Wildlife: Use and Conservation”. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA. Current Address: Texas A&M University College of Agriculture & Life Sciences Dept. of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences 210 Nagle Hall College Station, Texas 77843-2258 21 Tupinambis Lizards in Argentina: Implementing Management of a ~aditionally Exploited Resource LEE A. FITZGERALD, Jos~ MARIA CHANI, AND OSCAR E. DONADio 1\vo speciesof tegu lizards of the generaTupinambis, 1: teguixin, and 1: rufes- cens (fig. 21.1), are heavily exploited for their skins in Argentina. Each year, more than 1,250,000 skins are exportedfrom Argentina to the United States, Canada,Mexico, Hong Kong, Japan, and severalEuropean countries. Some skins are reexportedor madeinto exotic leatheraccessories, but the majority of the tegus are destinedto becomecowboy boots in Texas(Hemley 1984a).Sur- prisingly, the trade has continued at this level for at least 10 years (Hemley 1984a:Norman 1987). An internal Argentine market also exists foltegu skins, but it hasnot beenquantified. The large trade in Tupinambishas causedconcern among some government and nongovernmentorganizations because the biology of the lizards is essen- tially undescribed,and the effectson the tegu populationsand associatedbiotic communitiesof removing more than one million individuals annually are un- known. Although population declineshave not beendocumented, it seemspru- dent to study Tupinambisbiology and formulate long-term managementand conservationplans if the ecological, economic, and cultural valuesof the re- sourceare to be guaranteed. The Tupinambistrade is important to the Argentine economy.The export valueof the resourceis worth millions of dollars annually,and for rural peoples in northern Argentina with low wagesor intermittent employment,tegu hunt- ing is a significant sourceof income. -

Varanus Indicus Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Varanus indicus Varanus indicus System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Reptilia Squamata Varanidae Common name erebachi (Marovo), Pazifikwaran (German), regu (Roviana), kalabeck monitor (English), varan des indes (French), Indian monitor (English), Pacific monitor (English), Indian monitor lizard (English), mangrove monitor (English), sosi (Touo), ambon lizard (English), flower lizard (English), stillahavsvaran (Swedish), varano de manglar (Spanish), George's island monitor (English), varan des mangroves (French) Synonym Monitor chlorostigma Monitor douarrha Monitor kalabeck Tupinambis indicus Varanus guttatus Varanus tsukamotoi Monitor doreanus Monitor indicus Varanus chlorostigma Varanus indicus indicus Varanus leucostigma Varanus indicus kalabecki Varanus indicus spinulosis Similar species Varanus doreanus, Varanus indicus spinulosus Summary Varanus indicus (mangrove monitor) is a terrestrial-arboreal monitor lizard that has been introduced to several locations for its meat, skin or as a biological control agent. It has created a nuisance on many islands preying on domesticated chickens and scavenging the eggs of endangered sea turtles. Bufo marinus (cane toad) was introduced to control mangrove monitor populations in several locations, but this has led to devastating consequences. In many places both of these species are now serious pests, with little potential for successful control. view this species on IUCN Red List Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species profile Varanus indicus. Pag. 1 Available from: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1065 [Accessed 27 September 2021] FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Varanus indicus Species Description Varanus indicus (mangrove monitor) is darkly coloured with small yellow spots. It has a long, narrow head attached to a long neck. It has four strong legs, each with five sharp claws. -

Genetic Structure of Tupinambis Teguixin (Squamata: Teiidae), with Emphasis on Venezuelan Populations

Genetic structure of Tupinambis teguixin (Squamata: Teiidae), with emphasis on Venezuelan populations Ariana Gols-Ripoll*, Emilio A. Herrera & Jazzmín Arrivillaga Departamento de Estudios Ambientales, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Apdo. 89.000, Caracas 1080-A, Venezuela; [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received 26-I-2015. Corrected 25-VI-2015. Accepted 23-VII-2015. Abstract: Tupinambis teguixin, the common tegu, is the only species of the genus found in Venezuela. It is distributed in different bioregions in the Neotropics, some of them separated by geographic barriers that may restrict gene flow among populations. Thus, to assess this possibility, we tested the Paleogeographic hypothesis and the Riverine hypothesis for the divergence among populations. To this end, we evaluated the degree of genetic structuring in six populations of T. teguixin from Venezuela, plus one from Brazil and one from Ecuador. We used two molecular datasets, one with the populations from Venezuela (Venezuela dataset, 1 023 bp) and one including the other two (South America dataset, 665 bp), with 93 and 102 concatenated sequences from cytochrome b and ND4, and 38/37 haplotypes. We used three measures of genetic diversity: nucleotide diver- sity, haplotype diversity and number of polymorphic sites. Gene flow was estimated with the statistic ΦST and paired FST values. We also constructed a haplotype network. We found genetic structuring with (1) ΦST = 0.83; (2) high paired FST estimates (0.54 - 0.94); (3) haplotype networks with a well-defined geographic pattern; and (4) a single shared haplotype. The genetic structure does not seem to stem from geographic distance (r = 0.282, p = 0.209), but rather the product of an historic biogeographic event with the Mérida Andes and the Orinoco River (71.2 % of the molecular variance) as barriers. -

Spatial Ecology and Diet of the Argentine Black and White Tegu (Salvator Merianae) in Central Florida

SPATIAL ECOLOGY AND DIET OF THE ARGENTINE BLACK AND WHITE TEGU (SALVATOR MERIANAE) IN CENTRAL FLORIDA By MARIE-THERESE OFFNER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Marie-Therese Offner To my parents, for putting me in touch with nature ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude for the people who made it possible for me to fulfil my dreams, from the beginning of my work with tegus to the culmination of my thesis submission. My committee members each spent their time and talents shaping me to become a better biologist. Dr. Todd Campbell put me on the path. Dr. Steve Johnson accepted me under his tutelage and his continuous support ensured I was able to reach my goals. Dr. Mathieu Basille’s patience and persistence in teaching me how to code in R was invaluable and Dr. Christina Romagosa always knew how to keep up spirits. Much of my work would not have happened without my colleagues and friends past and present at Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Hillsborough County Conservation and Environmental Lands Management and RVR Horse Rescue (where I began removing tegus in 2012) including Sarah Funck, Jenny Eckles, Liz Barraco, Jake Edwards, Angeline Scotten, Bernie Kaiser, Ross Dickerson, and everyone else who works to defend Florida from the threat of invasives while conserving Florida’s unique wildlife. Their enthusiasm, dedication and passion is contagious. I may not have survived without my volunteers and interns Kayla Williams, Haley Hanson, Christin Meilink, Nick Espinosa, Jesse Goodyear and others who worked alongside me collecting data in the field, nor my family and friends who supported me through the years, especially my husband Gabriel Rogasner. -

The Diet of Adult Tupinambis Tegu/Xin (Sauria: Teiidae)

HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL , Vol. 4, pp. 15- 19 (1994) THE DIET OF ADULT TUPINAMBIS TE GU/XIN (SAURIA: TEIIDAE) IN THE EASTERN CHACO OF ARGENTINA CLAUDIA MERCOLLI AND ALBERTO YANOSKY El Bagual Ecological Reserve, J. J. Silva 814, 3600 - Formosa, Argentina Analysis of the number, weight and volume of food items in the digestive tracts of70 teiid lizards, Tupinambis teguixin, were obtained during spring-summer from areas neighbouring El Bagual EcologicalReserve in northeastern Argentina. The food items revealed the species to be a widely-rang'.ng opportunistic omnivorous forager. Tupinambis consumed a large . proportion of fruits, invertebrate and vertebrates. The species forages in both terrestrial and aquatic habitats, but no evidence was obtained for arboreal feeding habits. A sample of 27 to 49 digestive tracts is sufficient to reveal 80-90% of the prey types in the diet. INTRODUCTION Bagual Ecological Reserve (26° 59' 53 " S, 58° 56' 39" W) in northeasternArgentina. The area is characterized Tupinambis teguixin, the black tegu lizard, is a mem by flooded savannas and forests, subject to cyclic fires ber of the abundant fauna of South America and flooding(Neiff , 1986). The soils , originating from characterized by large adult size, relatively small volcanic ash of northwesternArgentina, are planosoles, hatchling size, sexual dimorphism as adults, large gley-humid and alluvial with poor drainage, and influ clutch size and reproduction limited to a brief breeding enced by Bermejo River lowlands (Helman, 1987). season (Yanosky & Mercolli, l 992a). However, no de The El Bagual Ecological Reserve annual mean tem tailed study of this lizard's diet has been published. -

Salvator Merianae) of Fernando De Noronha

C.R. Abrahão, J.C. Russell, J.C.R. Silva, F. Ferreira and R.A. Dias Abrahão, C.R.; J.C. Russell, J.C.R. Silva, F. Ferreira and R.A. Dias. Population assessment of a novel island invasive: tegu (Salvator merianae) of Fernando de Noronha Population assessment of a novel island invasive: tegu (Salvator merianae) of Fernando de Noronha C.R. Abrahão1,2, J.C. Russell3, J.C.R. Silva4, F. Ferreira2 and R.A. Dias2 1National Center of Conservation of Reptiles and Amphibians, Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Brazilian Ministry of Environment, Brazil. <[email protected]>. 2Laboratory of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Department of Preventive Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of São Paulo, Brazil. 3School of Biological Sciences and Department of Statistics, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand. 4Department of Veterinary Medicine, Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, Brazil. ABSTRACT Fernando de Noronha is an oceanic archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, 345 km offshore from the Brazilian coast. It comprises 21 islands and islets, of which the main island (FN) is 17 km2 with a rapidly growing tourism industry in the last decades. Despite being a protected area and bearing Ramsar and UNESCO World Heritage site status, it is threatened by multiple terrestrial invasive species since its colonisation in the early 16th century. Invasive species and the increasing tourism contributes to a list of at least 15 endangered or critically endangered species according to IUCN criteria. The black and white tegu (Salvator merianae) is the largest lizard in South America, occurring in most of the Brazilian territory and reaching up to 8 kg and 1.6 m from head to tail. -

Glasgow University Bolivia Expedition Report 2012

Glasgow University Bolivia Expedition Report 2012 A Joint Glasgow University & Bolivian Expedition to the Beni Savannahs of Bolivia Giant Anteater at sunset (photo by Jo Kingsbury) 1 | Page Contents 1. Introduction: Pages 3-10 2. Expedition Financial Summary 2012 Pages 11-12 3. New Large Mammal Records & Updated Species List Pages 13-20 4. Main Mammal Report Pages 21-69 5. Macaw Report: Pages 70-83 6. Savannah Passerine Report: Pages 84-97 7. Herpetology Report: Pages 98-107 8. Raptor Report: Pages 108-115 2 | Page 1. Introduction Figure 1.1: A view over the open grasslands of the Llanos de Moxos in the Beni Savannah Region of Northern Bolivia. Forest Islands on Alturas (high regions) are visible on the horizon. Written by Jo Kingsbury 3 | Page Bolivia Figure 1.2: Map of Bolivia in South AmeriCa Spanning an area of 1,098,581km², landlocked Bolivia is located at the heart of South America where it is bordered, to the north, by Brazil and Peru and, to the south, by Chile, Argentina and Paraguay (See Figure 1.2). Despite its modest size and lack of coastal and marine ecosystems, the country exhibits staggering geographical and climatic diversity. Habitats extend from the extreme and chilly heights of the Andean altiplano where vast salt flats, snow capped peaks and unique dry valleys dominate the landscape, to the low laying humid tropical rain forests and scorched savannah grasslands typical of the southern Amazon Basin. Bolivia’s biodiversity is equally rich and has earned it a well merited title as one of earths “mega-diverse” countries (Ibisch 2005).