The Phylogeny and Ontogeny of Autonomic Control of the Heart and Cardiorespiratory Interactions in Vertebrates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile-Like Physiology in Early Jurassic Stem-Mammals

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title: Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals Authors: Elis Newham1*, Pamela G. Gill2,3*, Philippa Brewer3, Michael J. Benton2, Vincent Fernandez4,5, Neil J. Gostling6, David Haberthür7, Jukka Jernvall8, Tuomas Kankanpää9, Aki 5 Kallonen10, Charles Navarro2, Alexandra Pacureanu5, Berit Zeller-Plumhoff11, Kelly Richards12, Kate Robson-Brown13, Philipp Schneider14, Heikki Suhonen10, Paul Tafforeau5, Katherine Williams14, & Ian J. Corfe8*. Affiliations: 10 1School of Physiology, Pharmacology & Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 2School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 3Earth Science Department, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 4Core Research Laboratories, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 5European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. 15 6School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 7Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 8Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 9Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 10Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 20 11Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Zentrum für Material-und Küstenforschung GmbH Germany. 12Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford, OX1 3PW, UK. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 13Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 14Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. -

Gallotia Caesaris, Lacertidae) from Different Habitats Author(S): M

Sexual Size and Shape Dimorphism Variation in Caesar's Lizard (Gallotia caesaris, Lacertidae) from Different Habitats Author(s): M. Molina-Borja, M. A. Rodríguez-Domínguez, C. González-Ortega, and M. L. Bohórquez-Alonso Source: Journal of Herpetology, 44(1):1-12. 2010. Published By: The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles DOI: 10.1670/08-266.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/08-266.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 1–12, 2010 Copyright 2010 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Sexual Size and Shape Dimorphism Variation in Caesar’s Lizard (Gallotia caesaris, Lacertidae) from Different Habitats 1,2 3 3 M. MOLINA-BORJA, M. A. RODRI´GUEZ-DOMI´NGUEZ, C. GONZA´ LEZ-ORTEGA, AND 1 M. L. BOHO´ RQUEZ-ALONSO 1Laboratorio Etologı´a, Departamento Biologı´a Animal, Facultad Biologı´a, Universidad La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain 3Centro Reproduccio´n e Investigacio´n del lagarto gigante de El Hierro, Frontera, El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain ABSTRACT.—We compared sexual dimorphism of body and head traits from adult lizards of populations of Gallotia caesaris living in ecologically different habitats of El Hierro and La Gomera. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Parasite Local Maladaptation in the Canarian Lizard Gallotia Galloti (Reptilia: Lacertidae) Parasitized by Haemogregarian Blood Parasite

Parasite local maladaptation in the Canarian lizard Gallotia galloti (Reptilia: Lacertidae) parasitized by haemogregarian blood parasite A. OPPLIGER,* R. VERNET &M.BAEZà *Zoological Museum, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 ZuÈ rich, Switzerland Laboratoire d'Ecologie, Ecole Normale SupeÂrieure, 46 rue d'Ulm, 75230 Paris, Cedex 05 France àDepartment of Zoology, University of La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain Keywords: Abstract cross-infection; Biologists commonly assume that parasites are locally adapted since they have host±parasite coevolution; shorter generation times and higher fecundity than their hosts, and therefore lizard; evolve faster in the arms race against the host's defences. As a result, parasites local adaptation. should be better able to infect hosts within their local population than hosts from other allopatric populations. However, recent mathematical modelling has demonstrated that when hosts have higher migration rates than parasites, hosts may diversify their genes faster than parasites and thus parasites may become locally maladapted. This new model was tested on the Canarian endemic lizard and its blood parasite (haemogregarine genus). In this host± parasite system, hosts migrate more than parasites since lizard offspring typically disperse from their natal site soon after hatching and without any contact with their parents who are potential carriers of the intermediate vector of the blood parasite (a mite). Results of cross-infection among three lizard populations showed that parasites were better at infecting individuals from allopatric populations than individuals from their sympatric population. This suggests that, in this host±parasite system, the parasites are locally maladapted to their host. ef®cient in infecting hosts from their native population, Introduction i.e. -

Gallotia Galloti Palmae, Fam

CITE THIS ARTCILE AS “IN PRESS” Basic and Applied Herpetology 00 (0000) 000-000 Chemical discrimination of pesticide-treated grapes by lizards (Gallotia galloti palmae, Fam. Lacertidae) Nieves Rosa Yanes-Marichal1, Angel Fermín Francisco-Sánchez1, Miguel Molina-Borja2* 1 Laboratorio de Agrobiología, Cabildo Insular de La Palma. 2 Grupo Etología y Ecología del Comportamiento, Departamento de Biología Animal, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands. * Correspondence: Phone: +34 922318341, Fax: +34 922318311, Email: [email protected] Received: 14 November 2016; returned for review: 1 December 2016; accepted 3 January 2017 Lizards from the Canary Islands may act as pests of several cultivated plants. As a case in point, vineyard farmers often complain about the lizards’ impact on grapes. Though no specific pesticide is used for lizards, several pesticides are used in vineyards to control for insects, fungi, etc. We therefore tested whether lizards (Gallotia galloti palmae) could detect and discriminate pesticide- treated from untreated grapes. To answer this question, we performed experiments with adults of both sexes obtained from three localities in La Palma Island. Two of them were a vineyard and a banana plantation that had been treated with pesticides and the other one was in a natural (untreated) site. In the laboratory, lizards were offered simultaneously one untreated (water sprayed) and one treated (with Folithion 50 LE, diluted to 0.1%) grape placed on small plates. The behaviour of the lizards towards the fruits was filmed and subsequently quantified by means of their tongue-flick, licks or bite rates to each of the grapes. -

Overwintering in Tegu Lizards

Overwintering in Tegu Lizards DENIS V. ANDRADE,1 COLIN SANDERS,1, 2 WILLIAM K. MILSOM,2 AND AUGUSTO S. ABE1 1 Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, SP, Brasil 2 Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada Abstract. The tegu, Tupinambis merianae, is a large South American teiid lizard, which is active only during part of the year (hot summer months), spending the cold winter months sheltered in burrows in the ground. This pattern of activity is accompanied by seasonal changes in preferred body temperature, metabolism, and cardiorespiratory function. In the summer months these changes are quite large, but during dormancy, the circadian changes in body temperature observed during the active season are abandoned and the tegus stay in the burrow and al- low body temperature to conform to the ambient thermal profile of the shelter. Metabolism is significantly depressed during dormancy and relatively insensitive to alterations in body temperature. As metabolism is lowered, ventilation, gas exchange, and heart rate are adjusted to match the level of metabolic demand, with concomitant changes in blood gases, blood oxygen transport capacity, and acid-base equilibrium. Seasonality and the Tegu Life Cycle As with any other ectothermic organism, the tegu lizard, Tupinambis merianae, depends on external heat sources to regulate body temperature. Although this type of thermoregulatory strategy conserves energy by avoiding the use of me- tabolism for heat production (Pough, 1983), it requires that the animal inhabit a suitable thermal environment to sustain activity. When the environment does not provide the range of temperatures that enables the animal to be active year round, many species of ectothermic vertebrates become seasonally inactive (Gregory, 1982). -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 26(2):121–122 • AUG 2019 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Mating. Chasing Bullsnakes ( Pituophisof catenifer Argentine sayi) in Wisconsin: Black-and-white On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared HistoryTegus of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis(Salvator) and Humans on Grenada: merianae ) A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 inRESEARCH Miami-Dade ARTICLES County, Florida, USA . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (AnolisJenna equestris M.) in FloridaCole, Cassidy Klovanish, and Frank J. Mazzotti .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 . More Than Mammals ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

The New Mode of Thought of Vertebrates' Evolution

etics & E en vo g lu t lo i y o h n a P r f y Journal of Phylogenetics & Kupriyanova and Ryskov, J Phylogen Evolution Biol 2014, 2:2 o B l i a o n l r o DOI: 10.4172/2329-9002.1000129 u g o y J Evolutionary Biology ISSN: 2329-9002 Short Communication Open Access The New Mode of Thought of Vertebrates’ Evolution Kupriyanova NS* and Ryskov AP The Institute of Gene Biology RAS, 34/5, Vavilov Str. Moscow, Russia Abstract Molecular phylogeny of the reptiles does not accept the basal split of squamates into Iguania and Scleroglossa that is in conflict with morphological evidence. The classical phylogeny of living reptiles places turtles at the base of the tree. Analyses of mitochondrial DNA and nuclear genes join crocodilians with turtles and places squamates at the base of the tree. Alignment of the reptiles’ ITS2s with the ITS2 of chordates has shown a high extent of their similarity in ancient conservative regions with Cephalochordate Branchiostoma floridae, and a less extent of similarity with two Tunicata, Saussurea tunicate, and Rinodina tunicate. We have performed also an alignment of ITS2 segments between the two break points coming into play in 5.8S rRNA maturation of Branchiostoma floridaein pairs with orthologs from different vertebrates where it was possible. A similarity for most taxons fluctuates between about 50 and 70%. This molecular analysis coupled with analysis of phylogenetic trees constructed on a basis of manual alignment, allows us to hypothesize that primitive chordates being the nearest relatives of simplest vertebrates represent the real base of the vertebrate phylogenetic tree. -

Amphibians and Reptiles of the Mediterranean Basin

Chapter 9 Amphibians and Reptiles of the Mediterranean Basin Kerim Çiçek and Oğzukan Cumhuriyet Kerim Çiçek and Oğzukan Cumhuriyet Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70357 Abstract The Mediterranean basin is one of the most geologically, biologically, and culturally complex region and the only case of a large sea surrounded by three continents. The chapter is focused on a diversity of Mediterranean amphibians and reptiles, discussing major threats to the species and its conservation status. There are 117 amphibians, of which 80 (68%) are endemic and 398 reptiles, of which 216 (54%) are endemic distributed throughout the Basin. While the species diversity increases in the north and west for amphibians, the reptile diversity increases from north to south and from west to east direction. Amphibians are almost twice as threatened (29%) as reptiles (14%). Habitat loss and degradation, pollution, invasive/alien species, unsustainable use, and persecution are major threats to the species. The important conservation actions should be directed to sustainable management measures and legal protection of endangered species and their habitats, all for the future of Mediterranean biodiversity. Keywords: amphibians, conservation, Mediterranean basin, reptiles, threatened species 1. Introduction The Mediterranean basin is one of the most geologically, biologically, and culturally complex region and the only case of a large sea surrounded by Europe, Asia and Africa. The Basin was shaped by the collision of the northward-moving African-Arabian continental plate with the Eurasian continental plate which occurred on a wide range of scales and time in the course of the past 250 mya [1]. -

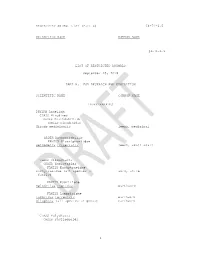

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Fitzgerald, LA, JM Chani, and OE Donadio

Fitzgerald, L.A., J.M. Chani, and O.E. Donadio. 1991. Tupinambis lizards in Argentina: Implementing management of a traditionally exploited resource. Pages 303-316 in Robinson, J. and K. Redford, eds. “Neotropical Wildlife: Use and Conservation”. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA. Current Address: Texas A&M University College of Agriculture & Life Sciences Dept. of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences 210 Nagle Hall College Station, Texas 77843-2258 21 Tupinambis Lizards in Argentina: Implementing Management of a ~aditionally Exploited Resource LEE A. FITZGERALD, Jos~ MARIA CHANI, AND OSCAR E. DONADio 1\vo speciesof tegu lizards of the generaTupinambis, 1: teguixin, and 1: rufes- cens (fig. 21.1), are heavily exploited for their skins in Argentina. Each year, more than 1,250,000 skins are exportedfrom Argentina to the United States, Canada,Mexico, Hong Kong, Japan, and severalEuropean countries. Some skins are reexportedor madeinto exotic leatheraccessories, but the majority of the tegus are destinedto becomecowboy boots in Texas(Hemley 1984a).Sur- prisingly, the trade has continued at this level for at least 10 years (Hemley 1984a:Norman 1987). An internal Argentine market also exists foltegu skins, but it hasnot beenquantified. The large trade in Tupinambishas causedconcern among some government and nongovernmentorganizations because the biology of the lizards is essen- tially undescribed,and the effectson the tegu populationsand associatedbiotic communitiesof removing more than one million individuals annually are un- known. Although population declineshave not beendocumented, it seemspru- dent to study Tupinambisbiology and formulate long-term managementand conservationplans if the ecological, economic, and cultural valuesof the re- sourceare to be guaranteed. The Tupinambistrade is important to the Argentine economy.The export valueof the resourceis worth millions of dollars annually,and for rural peoples in northern Argentina with low wagesor intermittent employment,tegu hunt- ing is a significant sourceof income.