Overwintering in Tegu Lizards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMNP Mountains Manual 2017

Mountain Adventures Manual utahmasternaturalist.org June 2017 UMN/Manual/2017-03pr Welcome to Utah Master Naturalist! Utah Master Naturalist was developed to help you initiate or continue your own personal journey to increase your understanding of, and appreciation for, Utah’s amazing natural world. We will explore and learn aBout the major ecosystems of Utah, the plant and animal communities that depend upon those systems, and our role in shaping our past, in determining our future, and as stewards of the land. Utah Master Naturalist is a certification program developed By Utah State University Extension with the partnership of more than 25 other organizations in Utah. The mission of Utah Master Naturalist is to develop well-informed volunteers and professionals who provide education, outreach, and service promoting stewardship of natural resources within their communities. Our goal, then, is to assist you in assisting others to develop a greater appreciation and respect for Utah’s Beautiful natural world. “When we see the land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” - Aldo Leopold Participating in a Utah Master Naturalist course provides each of us opportunities to learn not only from the instructors and guest speaKers, But also from each other. We each arrive at a Utah Master Naturalist course with our own rich collection of knowledge and experiences, and we have a unique opportunity to share that Knowledge with each other. This helps us learn and grow not just as individuals, but together as a group with the understanding that there is always more to learn, and more to share. -

Reptile-Like Physiology in Early Jurassic Stem-Mammals

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title: Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals Authors: Elis Newham1*, Pamela G. Gill2,3*, Philippa Brewer3, Michael J. Benton2, Vincent Fernandez4,5, Neil J. Gostling6, David Haberthür7, Jukka Jernvall8, Tuomas Kankanpää9, Aki 5 Kallonen10, Charles Navarro2, Alexandra Pacureanu5, Berit Zeller-Plumhoff11, Kelly Richards12, Kate Robson-Brown13, Philipp Schneider14, Heikki Suhonen10, Paul Tafforeau5, Katherine Williams14, & Ian J. Corfe8*. Affiliations: 10 1School of Physiology, Pharmacology & Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 2School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 3Earth Science Department, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 4Core Research Laboratories, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 5European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. 15 6School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 7Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 8Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 9Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 10Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 20 11Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Zentrum für Material-und Küstenforschung GmbH Germany. 12Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford, OX1 3PW, UK. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 13Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 14Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. -

Reproductionreview

REPRODUCTIONREVIEW Focus on Implantation Embryonic diapause and its regulation Flavia L Lopes, Joe¨lle A Desmarais and Bruce D Murphy Centre de Recherche en Reproduction Animale, Faculte´ de Me´decine Ve´te´rinaire, Universite´ de Montre´al, 3200 rue Sicotte, St-Hyacinthe, Quebec, Canada J2S7C6 Correspondence should be addressed to B D Murphy; Email: [email protected] Abstract Embryonic diapause, a condition of temporary suspension of development of the mammalian embryo, occurs due to suppres- sion of cell proliferation at the blastocyst stage. It is an evolutionary strategy to ensure the survival of neonates. Obligate dia- pause occurs in every gestation of some species, while facultative diapause ensues in others, associated with metabolic stress, usually lactation. The onset, maintenance and escape from diapause are regulated by cascades of environmental, hypophyseal, ovarian and uterine mechanisms that vary among species and between the obligate and facultative condition. In the best- known models, the rodents, the uterine environment maintains the embryo in diapause, while estrogens, in combination with growth factors, reinitiate development. Mitotic arrest in the mammalian embryo occurs at the G0 or G1 phase of the cell cycle, and may be due to expression of a specific cell cycle inhibitor. Regulation of proliferation in non- mammalian models of diapause provide clues to orthologous genes whose expression may regulate the reprise of proliferation in the mammalian context. Reproduction (2004) 128 669–678 Introduction recently been discussed in depth (Dey et al. 2004). In this presentation we address the characteristics of the embryo Embryonic diapause, also known as discontinuous devel- in diapause and focus on the mechanisms of regulation of opment or, in mammals, delayed implantation, is among this phenomenon, including the environmental and meta- the evolutionary strategies that ensure successful repro- bolic stimuli that induce and terminate this condition, the duction. -

Introduction to Pregnancy in Waiting: Embryonic Diapause in Mammals Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Embryonic Diapause

Proceedings of III International Symposium on Embryonic Diapause DOI: 10.1530/biosciprocs.10.001 Introduction to Pregnancy in Waiting: Embryonic Diapause in Mammals Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Embryonic Diapause BD Murphy1, K Jewgenow2, MB Renfree3, SE Ulbrich4 1Centre de recherche en reproduction et fertilité, Université de Montréal, Canada 2Leibniz-Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Berlin, Germany 3School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Australia 4Institute of Agricultural Sciences, ETH Zurich, Switzerland The capacity of the mammalian embryo to arrest development during early gestation is a topic that has fascinated biologists for over 150 years. The first known observation of this phenomenon was in a ruminant, the roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in 1854, later confirmed in a number of studies in the last century [1]. The phenomenon, now known as embryonic diapause, was then found to be present in a wide range of species and across multiple taxa. Since that time, its biological mystery has attracted studies by scientists from around the globe. The First International Symposium on the topic of embryonic diapause in mammals was held in 1963 at Rice University, Houston, Texas. It resulted in a proceedings volume entitled “Delayed Implantation”, edited by A.C. Enders [2]. The symposium was distinguished by the novel recognition of that era that a wide range of species had been identified with embryonic diapause, including rodents, marsupials and carnivores. The emerging technology of the time, particularly structural approaches, permitted new understanding of the events of diapause and embryo reactivation. The newest methods provided key data on the temporal window of implantation in rodents, introduced new physiological approaches, and illustrated some of the first transmission electron microscope investigations of the blastocyst. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Embryonic Diapause in Mammals and Dormancy in Embryonic Stem Cells with the European Roe Deer As Experimental Model

CSIRO PUBLISHING Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2021, 33, 76–81 https://doi.org/10.1071/RD20256 Embryonic diapause in mammals and dormancy in embryonic stem cells with the European roe deer as experimental model Vera A. van der WeijdenA,*, Anna B. Ru¨eggA,*, Sandra M. Bernal-UlloaA and Susanne E. UlbrichA,B AETH Zurich, Animal Physiology, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Universitaetstrasse 2, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland. BCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. In species displaying embryonic diapause, the developmental pace of the embryo is either temporarily and reversibly halted or largely reduced. Only limited knowledge on its regulation and the inhibition of cell proliferation extending pluripotency is available. In contrast with embryos from other diapausing species that reversibly halt during diapause, embryos of the roe deer Capreolus capreolus slowly proliferate over a period of 4–5 months to reach a diameter of approximately 4 mm before elongation. The diapausing roe deer embryos present an interesting model species for research on preimplantation developmental progression. Based on our and other research, we summarise the available knowledge and indicate that the use of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) would help to increase our understanding of embryonic diapause. We report on known molecular mechanisms regulating embryonic diapause, as well as cellular dormancy of pluripotent cells. Further, we address the promising application of ESCs to study embryonic diapause, and highlight the current knowledge on the cellular microenvironment regulating embryonic diapause and cellular dormancy. Keywords: dormancy, embryonic diapause, embryonic stem cells, European roe deer Capreolus capreolus. Published online 8 January 2021 Embryonic diapause conditions. The roe deer is the only known ungulate exhibiting The time between fertilisation and embryo implantation varies embryonic diapause. -

DORMANCY, CHILL ACCUMULATION, REST-BREAKING and FREEZE DAMAGE – What Are the Risks?

DORMANCY, CHILL ACCUMULATION, REST-BREAKING AND FREEZE DAMAGE – what are the risks? Kitren Glozer Department of Plant Sciences University of California Davis January 5, 2010 Once the chill requirement has been met, continued cold temperatures maintain the buds in a resting state, but the buds are ‘ready’ to begin growing because internal metabolic inhibitors are no longer present to withhold growth. Those inhibitors have decreased over time as the chill requirement has been satisfied. Bud growth will resume once temperatures become favorable and as the buds become less dormant, more metabolically active, cold-hardiness diminishes. Hardiness is lost very rapidly once buds begin growth. At full bloom, no cold-hardiness exists and killing temperatures do not have to be as low as when some or all cold-hardiness was present. Often there can be a warming period in January or early February that tends to increase flower bud respiration, reduce the depth of the dormant state, reducing winter hardiness. Thus, even without swollen buds or open flowers, temperatures can be low enough to reach the ‘critical temperature’ that will kill buds, and temperatures don’t have to be as cold or cold for as long as when buds are fully dormant for freeze damage to occur. Critical temperatures for the various tree fruits have been established in other areas, such as Michigan and Washington, however, California’s growing conditions are different enough that we can’t depend on the critical temperatures established elsewhere, and we do not have equivalents for California that are exact or published. Damage to the Tree Canopy The tree’s canopy (not just buds, flowers and fruits) may also be damaged by freezes, particularly during the transition into dormancy or out of dormancy when tissues are more active and less cold-hardy. -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 26(2):121–122 • AUG 2019 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Mating. Chasing Bullsnakes ( Pituophisof catenifer Argentine sayi) in Wisconsin: Black-and-white On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared HistoryTegus of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis(Salvator) and Humans on Grenada: merianae ) A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 inRESEARCH Miami-Dade ARTICLES County, Florida, USA . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (AnolisJenna equestris M.) in FloridaCole, Cassidy Klovanish, and Frank J. Mazzotti .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 . More Than Mammals ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Bud Dormancy in Apple Trees After Thermal Fluctuations

Bud dormancy in apple trees after thermal fluctuations Rafael Anzanello(1), Flávio Bello Fialho(2), Henrique Pessoa dos Santos(2), Homero Bergamaschi(3) and Gilmar Arduino Bettio Marodin(3) (1)Fundação Estadual de Pesquisa Agropecuária, RSC‑470, Km 170,8, Caixa Postal 44, CEP 95330‑000 Veranópolis, RS, Brazil. E‑mail: rafael‑[email protected] (2)Embrapa Uva e Vinho, Rua Livramento, no 515, Caixa Postal 130, CEP 95700‑000 Bento Gonçalves, RS, Brazil. E‑mail: [email protected], [email protected] (3)Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Avenida Bento Gonçalves, no 7.712, CEP 91540‑000 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. E‑mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract – The objective of this work was to evaluate the effect of heat waves on the evolution of bud dormancy, in apple trees with contrasting chilling requirements. Twigs of 'Castel Gala' and 'Royal Gala' were collected in orchards in Papanduva, state of Santa Catarina, Brazil, and were exposed to constant (3°C) or alternating (3 and 15°C for 12/12 hours) temperature, combined with zero, one or two days a week at 25°C. Two additional treatments were evaluated: constant temperature (3°C), with a heat wave of seven days at 25°C, in the beginning or in the middle of the experimental period. Periodically, part of the twigs was transferred to 25°C for daily budburst evaluation of apical and lateral buds. Endodormancy (dormancy induced by cold) was overcome with less than 330 chilling hours (CH) of constant cold in 'Castel Gala' and less than 618 CH in 'Royal Gala'. -

Understanding Molecular Mechanisms of Seed Dormancy for Improved Germination in Traditional Leafy Vegetables: an Overview

agronomy Review Understanding Molecular Mechanisms of Seed Dormancy for Improved Germination in Traditional Leafy Vegetables: An Overview Fernand S. Sohindji, Dêêdi E. O. Sogbohossou , Herbaud P. F. Zohoungbogbo, Carlos A. Houdegbe and Enoch G. Achigan-Dako * Laboratory of Genetics, Horticulture and Seed Science, Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, University of Abomey-Calavi, 01 BP 526 Tri Postal, Cotonou, Benin; [email protected] (F.S.S.); [email protected] (D.E.O.S.); [email protected] (H.P.F.Z.); [email protected] (C.A.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +229-95-39-32-83 Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 24 December 2019; Published: 1 January 2020 Abstract: Loss of seed viability, poor and delayed germination, and inaccessibility to high-quality seeds are key bottlenecks limiting all-year-round production of African traditional leafy vegetables (TLVs). Poor quality seeds are the result of several factors including harvest time, storage, and conservation conditions, and seed dormancy. While other factors can be easily controlled, breaking seed dormancy requires thorough knowledge of the seed intrinsic nature and physiology. Here, we synthesized the scattered knowledge on seed dormancy constraints in TLVs, highlighted seed dormancy regulation factors, and developed a conceptual approach for molecular genetic analysis of seed dormancy in TLVs. Several hormones, proteins, changes in chromatin structures, ribosomes, and quantitative trait loci (QTL) are involved in seed dormancy regulation. However, the bulk of knowledge was based on cereals and Arabidopsis and there is little awareness about seed dormancy facts and mechanisms in TLVs. To successfully decipher seed dormancy in TLVs, we used Gynandropsis gynandra to illustrate possible research avenues and highlighted the potential of this species as a model plant for seed dormancy analysis. -

Mammalogy Lecture 17 – Thermoregulation/Water Balance I

Mammalogy Lecture 17 – Thermoregulation/Water Balance I. Introduction. Obviously, mammals are endotherms; they regulate body temperature via metabolic processes by burning energy. For all endotherms, there is a Thermal Neutral Zone When TA is low, energy is expended to keep warm. When TA is high, energy is expended to keep cool But for every endothermic species, there is a thermal neutral zone, the range of ambient temperatures across which there’s no higher cost of homeothermy. TLC - highest temperature at which an endotherm expends energy to stay warm TUC - lowest temperature at which an endotherm expends energy to stay cool Obviously, when ambient temperatures are either below TLC or above TUC, there is a metabolic cost to homeothermy (maintaining a constant body temperature). II. Adaptations for Cold – Temperatures in Zone A A. Large Size - B. High Basal Metabolic Rate - Cold adapted species have a higher than expected basal metabolic rate. For example, Red foxes, Vulpes vulpes, have a BMR that’s nearly twice as high as similar sized canids in warmer regions. C. Insulation - Pelage - forms a barrier of warm air next to the surface of the animal. Blubber - subcutaneous fat is commonly used as an insulating mechanism in marine mammals. D. Regional Heterothermy Extremities may be allowed to cool, sometimes to very low temperatures. This is accomplished by vasoconstriction. Urocitellus paryii - toe pads may be 2 o - 5 o C Ondatra zibethicus – extremities are allowed to cool to water temperature E. Systemic Heterothermy – Adaptive Hypothermia Characterized by: - Decreased heart rate - Vasoconstriction - severe reduction of blood flow to the extremities - Decreased breathing rate - Suppression of shivering - Decreased oxygen consumption (decreased metabolic rate) - Decreased body temperature There is usually great energy savings associated with hypothermia. -

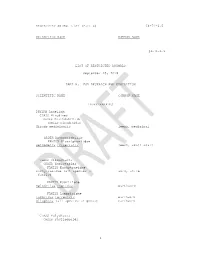

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes