3.3.1 Antimalarial Activity of Chemical Probes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neena Valecha1, Deepali Savargaonkar1, Bina Srivastava1, B

Valecha et al. Malar J (2016) 15:42 DOI 10.1186/s12936-016-1084-1 Malaria Journal RESEARCH Open Access Comparison of the safety and efficacy of fixed‑dose combination of arterolane maleate and piperaquine phosphate with chloroquine in acute, uncomplicated Plasmodium vivax malaria: a phase III, multicentric, open‑label study Neena Valecha1, Deepali Savargaonkar1, Bina Srivastava1, B. H. Krishnamoorthy Rao2, Santanu K. Tripathi3, Nithya Gogtay4, Sanjay Kumar Kochar5, Nalli Babu Vijaya Kumar6, Girish Chandra Rajadhyaksha7, Jitendra D. Lakhani8, Bhagirath B. Solanki9, Rajinder K. Jalali10, Sudershan Arora10, Arjun Roy10, Nilanjan Saha10, Sunil S. Iyer10, Pradeep Sharma10 and Anupkumar R. Anvikar1* Abstract Background: Chloroquine has been the treatment of choice for acute vivax malaria for more than 60 years. Malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax has recently shown resistance to chloroquine in some places. This study compared the efficacy and safety of fixed dose combination (FDC) of arterolane maleate and piperaquine phosphate (PQP) with chloroquine in the treatment of uncomplicated vivax malaria. Methods: Patients aged 13–65 years with confirmed mono-infection of P. vivax along with fever or fever in the previ- ous 48 h were included. The 317 eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive FDC of arterolane maleate and PQP (n 159) or chloroquine (n 158) for 3 days. Primaquine was given as an anti-relapse measure on day 3 and continued= for 14 consecutive days.= Primary efficacy analysis included assessment of the proportion of aparasitaemic and afebrile patients at 72 h. Safety endpoints were analysis of adverse events, vital signs, laboratory data, and abnor- malities on electrocardiograph. Patients participated in the study for at least 42 days. -

Review Article Efforts Made to Eliminate Drug-Resistant Malaria and Its Challenges

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2021, Article ID 5539544, 12 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5539544 Review Article Efforts Made to Eliminate Drug-Resistant Malaria and Its Challenges Wote Amelo 1,2,3 and Eyasu Makonnen 1,2 1Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2Center for Innovative Drug Development and Therapeutic Trials for Africa (CDT-Africa), Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 3Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, School of Pharmacy, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia Correspondence should be addressed to Wote Amelo; [email protected] Received 21 January 2021; Accepted 9 August 2021; Published 30 August 2021 Academic Editor: Jane Hanrahan Copyright © 2021 Wote Amelo and Eyasu Makonnen. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Since 2000, a good deal of progress has been made in malaria control. However, there is still an unacceptably high burden of the disease and numerous challenges limiting advancement towards its elimination and ultimate eradication. Among the challenges is the antimalarial drug resistance, which has been documented for almost all antimalarial drugs in current use. As a result, the malaria research community is working on the modification of existing treatments as well as the discovery and development of new drugs to counter the resistance challenges. To this effect, many products are in the pipeline and expected to be marketed soon. In addition to drug and vaccine development, mass drug administration (MDA) is under scientific scrutiny as an important strategy for effective utilization of the developed products. -

Artemisinin Resistance: Current Status and Scenarios for Containment

REVIEWS Artemisinin resistance: current status and scenarios for containment Arjen M. Dondorp*‡, Shunmay Yeung*§, Lisa White*‡, Chea Nguon§, Nicholas P.J. Day*‡, Duong Socheat§|| and Lorenz von Seidlein*¶ Abstract | Artemisinin combination therapies are the first-line treatments for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in most malaria-endemic countries. Recently, partial artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum malaria has emerged on the Cambodia–Thailand border. Exposure of the parasite population to artemisinin monotherapies in subtherapeutic doses for over 30 years, and the availability of substandard artemisinins, have probably been the main driving force in the selection of the resistant phenotype in the region. A multifaceted containment programme has recently been launched, including early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, decreasing drug pressure, optimising vector control, targeting the mobile population, strengthening management and surveillance systems, and operational research. Mathematical modelling can be a useful tool to evaluate possible strategies for containment. Parenteral In nearly all countries in which malaria is endemic, antimalarial properties (artemisinin) was identified, and Administered by injection. artemisinin combination therapies (ACT) are now the several more potent derivatives were synthesized, includ- recommended first-line therapy for uncomplicated ing artesunate, artemether and dihydroartemisinin11 Plasmodium falciparum malaria, a policy endorsed by (FIG. 1). Artemisinin derivatives have an excellent safety the WHO1. This change in policy followed a period profile in the treatment of malaria, a rapid onset of action of increasing failure rates with chloroquine and later and are active against the broadest range of stages in the sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine treatment, which arose life cycle of Plasmodium spp. compared with other anti- from the development of resistant P. -

Update Tot 30-04-2020 1. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine for The

Update tot 30-04-2020 1. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine for the Prevention or Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Africa: Caution for Inappropriate Off-Label Use in Healthcare Settings. Abena PM, Decloedt EH, Bottieau E, Suleman F, Adejumo P, Sam-Agudu NA, et al. Am j trop med hyg. 2020. 2. Evaluation of Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy Using Ultra-Widefield Fundus Autofluorescence: Peripheral Findings in the Retinopathy. Ahn SJ, Joung J, Lee BR. American journal of ophthalmology. 2020;209:35-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2019.09.008. Epub 2019 Sep 14. 3. COVID-19 research has overall low methodological quality thus far: case in point for chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine. Alexander PE, Debono VB, Mammen MJ, Iorio A, Aryal K, Deng D, et al. J clin epidemiol. 2020. 4. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine in the Era of SARS - CoV2: Caution on Their Cardiac Toxicity. Bauman JL, Tisdale JE. Pharmacotherapy. 2020. 5. Repositioned chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as antiviral prophylaxis for COVID-19: A protocol for rapid systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Chang R, Sun W-Z. medRxiv. 2020:2020.04.18.20071167. 6. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Colson P, Rolain J-M, Lagier J-C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105932-. 7. Dose selection of chloroquine phosphate for treatment of COVID-19 based on a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model. Cui C, Zhang M, Yao X, Tu S, Hou Z, Jie En VS, et al. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2020. 8. Hydroxychloroquine; Why It Might Be Successful and Why It Might Not Be Successful in the Treatment of Covid-19 Pneumonia? Could It Be A Prophylactic Drug? Deniz O. -

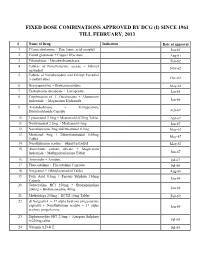

Fixed Dose Combinations Approved by Dcg (I) Since 1961 Till February, 2013

FIXED DOSE COMBINATIONS APPROVED BY DCG (I) SINCE 1961 TILL FEBRUARY, 2013 # Name of Drug Indication Date of approval 1. Cyanocobalamine + Zinc tannic acid complex Jan-61 2. Cobalt glutamate + Copper Glycinate Aug-61 3. Fibrinolysin + Desoxyribonuclease Feb-62 4. Tablets of Norethisterone acetate + Ethinyl Nov-62 oestradiol 5. Tablets of Norethynodrel and Ethinyl Estradiol 3-methyl ether Dec-62 6. Broxyquinoline + Brobenzoxalidine May-63 7. Testosterone decanoate + Isocaproate Jan-64 8. Combination of L Oxethazaine + Aluminium hydroxide + Magnesium Hydroxide Jun-66 9. Amylobarbitone + Trifluperazine Dihydrochloride Capsule Feb-67 10. Lynestronol 2.5mg + Mestranol 0.075mg Tablet Apr-67 11. Northynodrel 2.5mg + Mestranol 0.1mg Jun-67 12. Norethisterone 2mg and Mestranol 0.1mg May-67 13. Mestranol 4mg + Ethinyloestradial 0.05mg May-67 Tablet 14. Norethisterane acetate + ethinyl estradiol May-67 15. Aluminium sodium silicate + Magnesium hydroxide + Methypolysiloxane Tablet Jun-67 16. Ammoidin + Amidine Jul-67 17. Fluocortolene + Flucortolene Caproate Jul-68 18. Norgestrel + Ethinyloestradiol Tablet Aug-68 19. Folic Acid 0.5mg + Ferrous Sulphate 150mg Jan-69 Capsule 20. Tetracycline HCl 250mg + Broxyquinoline 200mg + Brobenzoxadine 40mg Jan-69 21. Methyldopa 250mg + HCTZ 15mg Tablet Feb-69 22. dl Norgestrel + 17 alpha hydroxy progesterone caproate + Norethisterone acetate + 17 alpha Jan-69 acetoxy progesterone 23. Diphenoxylate HCl 2.5mg + Atropine Sulphate 0.025mg tablet Jul-69 24. Vitamin A,D & E Jul-69 25. Lutin 0.1gm + Vit 0.1gm + Vit K1 2.5mg + Dicalcium Phosphate 0.1gm + Carlozochrome Jul-69 Salicylate 1mg tablet 26. Vit K 1 5mg + Calcium Lactolionate 100 m g+ Carlozocrome Salicylate 2.5mg + Phenol 0.5% Jul-69 + Lignocaine Hcl 1% injection 27. -

Evolution of Plasmodium Falciparum Drug Resistance: Implications for the Development and Containment of Artemisinin Resistance

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 65, 465-475, 2012 Invited Review Evolution of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance: implications for the development and containment of artemisinin resistance Toshihiro Mita1,2* and Kazuyuki Tanabe3,4 1Department of Molecular and Cellular Parasitology, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo 113-8421; 2Department of International Affairs and Tropical Medicine, Tokyo Women's Medical University, Tokyo 162-8666; and 3Laboratory of Malariology and 4Department of Molecular Protozoology, Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Osaka 565-0871, Japan (Received March 15, 2012) CONTENTS: 1. Introduction 5. Artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) and 2. Life cycle of P. falciparum resistance to artemisinins 3. Mechanisms of P. falciparum resistance to conven- 5–1. Artemisinin derivatives tional antimalarial drugs 5–2. ACTs 3–1. Chloroquine 5–3. Resistance and reduced susceptibility to arte- 3–2. Pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine misinins 4. Geographical spread of resistance to conventional 6. The Thailand-Cambodia border and the contain- antimalarial drugs ment of artemisinin resistance 4–1. Chloroquine 6–1. Thailand-Cambodia border: epicenter of drug 4–2. Pyrimethamine resistance 4–3. Sulfadoxine 6–2. Resistance and the Greater Mekong 6–3. Implications for the containment of artemisi- nin resistance 7. Concluding remarks SUMMARY: Malaria is a protozoan disease transmitted by the bite of the Anopheles mosquito. Among five species that can infect humans, Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for the most severe human malaria. Resistance of P. falciparum to chloroquine and pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine, conventionally used antimalarial drugs, is already widely distributed in many endemic areas. As a result, artemisinin- based combination therapies have been rapidly and widely adopted as first-line antimalarial treatments since the mid-2000s. -

Malaria Medicines Landscape

2015 Malaria Medicines Landscape MARCH 2015 UNITAID Secretariat World Health Organization Avenue Appia 20 CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland T +41 22 791 55 03 F +41 22 791 48 90 [email protected] www.unitaid.org UNITAID is hosted and administered by the World Health Organization © 2015 World Health Organization (Acting as the host organization for the Secretariat of UNITAID) The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind either expressed or implied. The responsibility and use of the material lie with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. This report was prepared by Katerina Galluzzo and Alexandra Cameron with support from UNITAID. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the author to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. -

WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria

GTMcover-production.pdf 11.1.2006 7:10:05 GUIDELINES FOR THE TREATMENT O F M A L A R I A GUIDELINES FOR THE TREATMENT OF MALARIA Guidelines for the treatment of malaria Guidelines for the treatment of malaria WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Guidelines for the treatment of malaria/World Health Organization. Running title: WHO guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 1. Malaria – drug therapy. 2. Malaria – diagnosis. 3. Antimalarials – administration and dosage. 4. Drug therapy, Combination. 5. Guidelines. I. Title. II. Title: WHO guidelines for the treatment of malaria. ISBN 92 4 154694 8 (NLM classification: WC 770) ISBN 978 92 4 154694 2 WHO/HTM/MAL/2006.1108 © World Health Organization, 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20, avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel. +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

New Trends in Anti-Malarial Agents

Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2002, 9, 1435-1456 1435 New Trends in Anti-Malarial Agents 1,2 3 2 Michel Frédérich* , Jean-Michel Dogné* , Luc Angenot1 and Patrick De Mol 1 Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, Natural and Synthetic Drugs Research Center, University of Liège, CHU Sart- Tilman B36, 4000 Liège, Belgium 2 Laboratory of Medical Microbiology, University of Liège, CHU Sart-Tilman B23, 4000 Liège, Belgium 3 Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Natural and Synthetic Drugs Research Center, University of Liège, CHU Sart-Tilman B36, 4000 Liège, Belgium Abstract: Malaria is the major parasitic infection in many tropical and subtropical regions, leading to more than one million deaths (principally young African children) out of 400 million cases each year (WHO world health report 2000). More than half of the world’s population live in areas where they remain at risk of malaria infection. During last years, the situation has worsened in many ways, mainly due to malarial parasites becoming increasingly resistant to several antimalarial drugs. Furthermore, the control of malaria is becoming more complicated by the parallel spread of resistance of the mosquito vector to currently available insecticides. Discovering new drugs in this field is therefore a health priority. Several new molecules are under investigation. This review describes the classical treatments of malaria and the latest discoveries in antimalarial agents, especially artemisinin and its recent derivatives as well as the novel peroxidic compounds. 1. INTRODUCTION virulence and drug resistance. P. falciparum may cause the conditions known as cerebral malaria, which is often fatal. Malaria is the major parasitic infection in many tropical and subtropical regions, leading to more than one million deaths The life cycle of the malaria parasite is complex [Fig. -

Medical Review(S) Review of Request for Priority Review

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 22-268 MEDICAL REVIEW(S) REVIEW OF REQUEST FOR PRIORITY REVIEW To: Edward Cox, MD, MPH Director, Office of Antimicrobial Products Through: Renata Albrecht, M.D Director, DSPTP, OAP From: Joette M. Meyer, Pharm.D. Acting Medical Team Leader, DSPTP, OAP NDA: 22-268 Submission Date: 6/27/08 Date Review Completed 7/25/08 Product: Coartem (artemether/lumefantrine) Sponsor: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation East Hanover, NJ Proposed Indication: Treatment of malaria in patients of 5kg body weight and above with acute, uncomplicated infections due to Plasmodium falciparum or mixed infections including P. falciparum Proposed Dosing Regimen: A standard 3-day treatment schedule with a total of 6 doses is recommended and dosed based on bodyweight: 5 kg to < 15 kg: One tablet as an initial dose, 1 tablet again after 8 hours and then 1 tablet twice daily (morning and evening) for the following two days 15 kg to < 25 kg bodyweight: Two tablets as an initial dose, 2 tablets again after 8 hours and then 2 tablets twice daily (morning and evening) for the following two days 25 kg to < 35 kg bodyweight: Three tablets as an initial dose, 3 tablets again after 8 hours and then 3 tablets twice daily (morning and evening) for the following two days 35 kg bodyweight and above: Four tablets as a single initial dose, 4 tablets again after 8 hours and then 4 tablets twice daily (morning and evening) for the following two days Abbreviations A artemether ACT artemisinin-based combination therapy AL artemether-lumefantrine -

PHARMACOLOGY of NEWER ANTIMALARIAL DRUGS: REVIEW ARTICLE Bhuvaneshwari1, Souri S

REVIEW ARTICLE PHARMACOLOGY OF NEWER ANTIMALARIAL DRUGS: REVIEW ARTICLE Bhuvaneshwari1, Souri S. Kondaveti2 HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Bhuvaneshwari, Souri S. Kondaveti. ‖Pharmacology of Newer Antimalarial Drugs: Review Article‖. Journal of Evidence based Medicine and Healthcare; Volume 2, Issue 4, January 26, 2015; Page: 431-439. ABSTRACT: Malaria is currently is a major health problem, which has been attributed to wide spread resistance of the anopheles mosquito to the economical insecticides and increasing prevalence of drug resistance to plasmodium falciparum. Newer drugs are needed as there is a continual threat of emergence of resistance to both artemisins and the partner medicines. Newer artemisinin compounds like Artemisone, Artemisnic acid, Sodium artelinate, Arteflene, Synthetic peroxides like arterolane which is a synthetic trioxolane cognener of artemisins, OZ439 a second generation synthetic peroxide are under studies. Newer artemisinin combinations include Arterolane(150mg) + Piperaquine (750mg), DHA (120mg) + Piperaquine(960mg) (1:8), Artesunate + Pyronardine (1:3), Artesunate + Chlorproguanil + Dapsone, Artemisinin (125mg) + Napthoquine (50mg) single dose and Artesunate + Ferroquine.Newer drugs under development including Transmission blocking compounds like Bulaquine, Etaquine, Tafenoquine, which are primaquine congeners, Spiroindalone, Trioxaquine DU 1302, Epoxamicin, Quinolone 3 Di aryl ether. Newer drugs targeting blood & liver stages which include Ferroquine, Albitiazolium – (SAR – 97276). Older drugs with new use in malaria like beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, protease inhibitors, Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors, methotrexate, Sevuparin sodium, auranofin, are under preclinical studies which also target blood and liver stages. Antibiotics like Fosmidomycin and Azithromycin in combination with Artesunate, Chloroquine, Clindamycin are also undergoing trials for treatment of malaria. Vaccines - RTS, S– the most effective malarial vaccine tested to date. -

Revised37 Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria – 2Nd Edition, Rev

Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, 2nd edition – Rev. 1 The following sections, from 8.4 to 8.6 have been revised to reflect the change of treatment of severe falciparum malaria in children 8.4 Specific antimalarial treatment It is essential that effective, parenteral (or rectal) antimalarial treatment in full doses is given promptly in severe malaria. Two classes of medicines are available for the parenteral treatment of severe malaria: the cinchona alkaloids (quinine and quinidine) and the artemisinin derivatives (artesunate, artemether and artemotil). Parenteral chloroquine is no longer recommended for the treatment of severe malaria, because of widespread resistance. Intramuscular sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine is also not recommended. 8.4.1 Artemisinin derivatives Various artemisinin derivatives have been used in the treatment of severe malaria, including artemether, artemisinin, artemotil and artesunate. Randomized trials comparing artesunate and quinine from South-East Asia show clear evidence of benefit with artesunate. In a multi-centre trial, which enrolled 1461 patients (including 202 children < 15 years old), mortality was reduced by 34.7% in the artesunate group when compared to the quinine group. The results of this and smaller trials are consistent and suggest that artesunate is the treatment of choice for adults with severe malaria. Until recently there was insufficient evidence to make a similar recommendation in children, from high transmission settings, so the guidelines for this important patient group did not recommend artesunate above treatment with either artemether or quinine. This has now changed with the publication of the AQUAMAT trial*, a multi-centre study conducted in African children hospitalized with severe malaria.