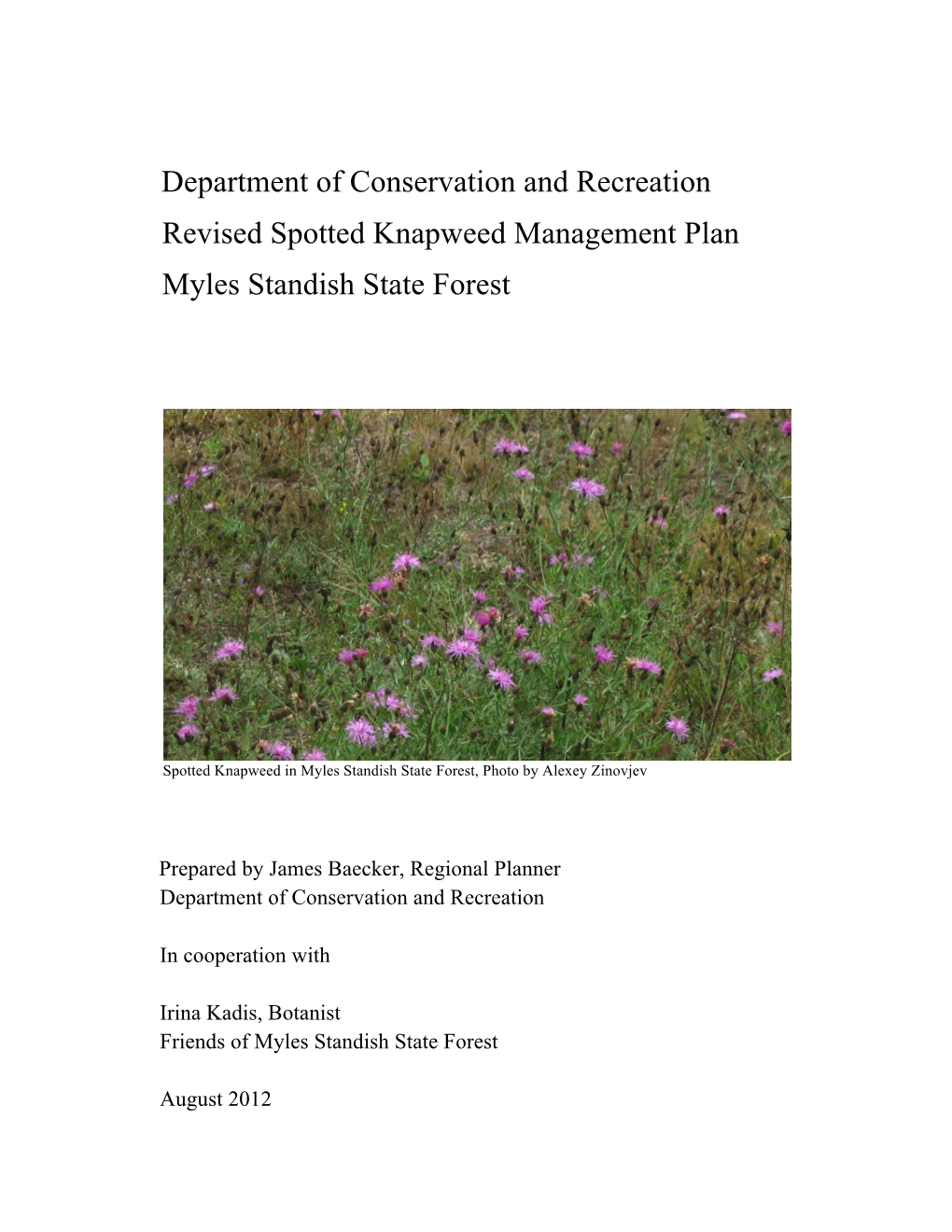

Department of Conservation and Recreation Revised Spotted Knapweed Management Plan Myles Standish State Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taksonomska I Korološka Analiza Roda Centaurea L. U Herbariju Ive I Marije Horvat (ZAHO)

Taksonomska i korološka analiza roda Centaurea L. u Herbariju Ive i Marije Horvat (ZAHO) Uremović, Sanja Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:945197 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-10 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU Prirodoslovno – matematiĉki fakultet BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK Sanja Uremović Taksonomska i korološka analiza roda Centaurea L. u Herbariju Ive i Marije Horvat (ZAHO) Diplomski rad Zagreb, 2011. SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU Prirodoslovno – matematiĉki fakultet BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK Sanja Uremović Taksonomska i korološka analiza roda Centaurea L. u Herbariju Ive i Marije Horvat (ZAHO) Diplomski rad Zagreb, 2011. Ovaj diplomski rad izrađen je na Botaničkom zavodu Prirodoslovno – matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu pod voditeljstvom prof.dr.sc. Božene Mitić, radi stjecanja zvanja profesor biologije i kemije. Zahvala Tijekom izrade ovog diplomskog rada pruţena mi je velika pomoć, struĉni savjeti te razumijevanje od strane mentorice prof. dr. sc. Boţene Mitić, kojoj se najljepše zahvaljujem. TakoĊer, doc. dr. sc. Igoru Boršiću i doc. dr. sc. Sandru Bogdanoviću veliko hvala na bezrezervnoj pomoći, na brojnim struĉnim savjetima, strpljenju i potpori tijekom izrade ovog rada. Hvala Margeriti, Mariji, Ţeljki, Tamari i Nives na savjetima, nesebiĉnom razumijevanju i podršci, ne samo tijekom izrade ovog diplomskog rada, nego i tijekom studiranja. Konaĉno, za moju obitelj ne postoji dovoljno veliko hvala za svu podršku, strpljenje, razumijevanje i sve što su uĉinili za mene, no ipak, mama, tata, seka, Vjeko – hvala vam što ste uvijek uz mene. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Przyroda Sudetów 9

Tom 9 2006 EUROREGION NEISSE - NISA - NYSA Projekt jest dofinansowany przez Unię Europejską ze środków Europejskiego Funduszu Rozwoju Regionalnego w ramach Programu Inicjatywy Wspólnotowej INTERREG IIIA Wolny Kraj Związkowy Saksonia – Rzeczpospolita Polska (Województwo Dolnośląskie), w Euroregionie Nysa oraz budżet państwa. oraz Wojewódzki Fundusz Ochrony Œrodowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej we Wroc³awiu 1 MUZEUM PRZYRODNICZE w JELENIEJ GÓRZE ZACHODNIOSUDECKIE TOWARZYSTWO PRZYRODNICZE PRZYRODA SUDETÓW ROCZNIK Tom 9, 2006 JELENIA GÓRA 2006 2 PRZYRODA SUDETÓW t. 9(2006): 3-6 Jacek Urbaniak Redaktor wydawnictwa ANDRZEJ PACZOS Redaktor naczelny BOŻENA GRAMSZ Stanowisko Nitella syncarpa Zespó³ redakcyjny BO¯ENA GRAMSZ (zoologia) CZES£AW NARKIEWICZ (botanika) (THUILL .) CHEVALL . 1827 (Charophyta) ANDRZEJ PACZOS (przyroda nieożywiona) Recenzenci TOMASZ BLAIK (Opole), ADAM BORATYŃSKI (Kórnik), w masywie Gromnika MAREK BUNALSKI (Poznań), ANDRZEJ CHLEBICKI (Kraków), ANDRZEJ HUTOROWICZ (Olsztyn), LUDWIK LIPIŃSKI (Gorzów Wlkp.) ADAM MALKIEWICZ (Wrocław), PIOTR MIGOŃ (Wrocław), ROMUALD MIKUSEK (Kudowa Zdrój), JULITA MINASIEWICZ (Gdańsk), TADEUSZ MIZERA (Poznań), KRYSTYNA PENDER (Wrocław), Wstęp ŁUKASZ PRZYBYŁOWICZ (Kraków), PIOTR REDA (Zielona Góra), TADEUSZ STAWARCZYK (Wrocław), EWA SZCZĘŚNIAK (Wrocław), W polskiej florze ANDRZEJ TRACZYK (Wrocław), WANDA M. WEINER (Kraków), ramienic (Charophyta) JAN ŻARNOWIEC (Bielsko-Biała) występuje pięć z sze- ściu rodzajów z tej T³umaczenie streszczeñ (na j. niemiecki) ALFRED BORKOWSKI wysoko uorganizowa- (na j. czeski) JIØÍ DVOØÁK nej gromady glonów, a mianowicie: Chara, Dtp „AD REM”, tel. 075 75 222 15, www.adrem.jgora.pl Nitella, Nitellopsis, Tolypella i Lychno- Opracowanie thamnus. Najbardziej kartograficzne „PLAN”, tel. 075 75 260 77 (str. 72, 146, 148) rozpowszechnionym, nie tylko w Polsce, ale Druk ANEX, Wrocław i w całej Europie, jest rodzaj Chara, którego Nak³ad 1200 egz. -

Sargetia Series Scientia Naturae

www.mcdr.ro / www.cimec.ro A C T A M U S E I D E V E N S I S S A R G E T I A SERIES SCIENTIA NATURAE XXI DEVA - 2008 www.mcdr.ro / www.cimec.ro EDITORIAL BOARD SILVIA BURNAZ MARCELA BALAZS DANIELA MARCU Computer Editing: SILVIA BURNAZ, DORINA DAN Advisory board/ Referenţi ştiinţifici: Prof. univ. dr. Dan Grigorescu – The University of Bucharest Prof. univ. dr. Vlad Codrea – The University Babeş-Bolyai Cluj-Napoca Prof. univ. dr. Lászlo Rákosy – The University Babeş-Bolyai Cluj-Napoca Conf. univ. dr. Marcel Oncu – The University Babeş-Bolyai Cluj-Napoca SARGETIA SARGETIA ACTA MUSEI DEVENSIS ACTA MUSEI DEVENSIS SERIES SCIENTIA NATURAE SERIES SCIENTIA NATURAE L’adresse Address: Le Musée de la Civilisation Dacique et The Museum of Dacian and Roman Romaine Civilization La Section des Sciences Naturelles The Natural Sciences Section Rue 1 Decembrie 39 DEVA 39, 1 Decembrie Street – DEVA ROUMANIE ROMANIA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Published by the Museum of Dacian and Roman Civilisation Deva All rights reserved Authors bear sole responsibility for the contents of their contributions Printed by qual media Producţie şi Simţire Publicitară & Mediamira Publishing House ISSN 1224-7464 www.mcdr.ro / www.cimec.ro S U M M A R Y – S O M M A I R E Pag. ŞTEFAN VASILE - A new microvertebrate site from the Upper 5 Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) deposits of the Haţeg Basin DIANA PURA - Early Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) 17 fossiliferous deposits from the Ohaba-Ponor area, SW Romania-preliminary study VLAD A. -

Overview of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects, Pharmacokinetic Properties

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2018) 39: 787–801 © 2018 CPS and SIMM All rights reserved 1671-4083/18 www.nature.com/aps Review Article Overview of the anti-inflammatory effects, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacies of arctigenin and arctiin from Arctium lappa L Qiong GAO, Mengbi YANG, Zhong ZUO* School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China Abstract Arctigenin (AR) and its glycoside, arctiin, are two major active ingredients of Arctium lappa L (A lappa), a popular medicinal herb and health supplement frequently used in Asia. In the past several decades, bioactive components from A lappa have attracted the attention of researchers due to their promising therapeutic effects. In the current article, we aimed to provide an overview of the pharmacology of AR and arctiin, focusing on their anti-inflammatory effects, pharmacokinetics properties and clinical efficacies. Compared to acrtiin, AR was reported as the most potent bioactive component of A lappa in the majority of studies. AR exhibits potent anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) via modulation of several cytokines. Due to its potent anti-inflammatory effects, AR may serve as a potential therapeutic compound against both acute inflammation and various chronic diseases. However, pharmacokinetic studies demonstrated the extensive glucuronidation and hydrolysis of AR in liver, intestine and plasma, which might hinder its in vivo and clinical efficacy after oral administration. Based on the reviewed pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characteristics of AR, further pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of AR via alternative administration routes are suggested to promote its ability to serve as a therapeutic agent as well as an ideal bioactive marker for A lappa. -

Differentiation Between Diploid and Tetraploid Centaurea Phrygia: Mating Barriers, Morphology and Geographic Distribution

Preslia 84: 1–32, 2012 1 Differentiation between diploid and tetraploid Centaurea phrygia: mating barriers, morphology and geographic distribution Diploidní a tetraploidní Centaurea phrygia – reprodukční bariéry, morfologie a rozšíření Petr K o u t e c k ý1, Jan Š t ě p á n e k2,3 & Tereza B a ď u r o v á1 1University of South Bohemia, Faculty of Science, Department of Botany, Branišovská 31, České Budějovice, CZ-370 05, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]; 2Herbarium of the Charles University in Prague, Benátská 2, Praha, CZ-120 00; 3Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Zámek 1, Průhonice, CZ-252 43, e-mail: [email protected] Koutecký P., Štěpánek J. & Baďurová T. (2012): Differentiation between diploid and tetraploid Centaurea phrygia: mating barriers, morphology, and geographic distribution. – Preslia 84: 1–32. Karyological variation, reproductive isolation, morphological differentiation and geographic distri- bution of the cytotypes of Centaurea phrygia were investigated in Central Europe. Occurrence of two dominant cytotypes, diploid (2n = 22) and tetraploid (2n = 44), was confirmed and additionally triploid, pentaploid and hexaploid ploidy levels identified using flow cytometry. Allozyme variation as well as morphological and genome size data suggest an autopolyploid origin of the tetraploids. Crossing experiments and flow cytometric screening of mixed populations revealed strong repro- ductive isolation of the cytotypes. Multivariate morphometric analysis revealed significant differen- tiation -

Tome 15, 2008

CUPRINS ALARU VICTOR, TROFIM ALINA, MELNICIUC CRISTINA, DONU NATALIA – Structura taxonomic i ecologic a comunitilor de alge edafice din agrofitocenozele raioanelor de nord ale Republicii Moldova ................................... 3 ALARU VICTOR, TROFIM ALINA, ALARU VASILE – Diversitatea taxonomic i rolul algoflorei în procesele de epurare biologic a apelor din râul Cogâlnic (R. Moldova)....................................................................................................................... 7 ALARU VICTOR, TROFIM ALINA, ALARU VASILE – Utilizarea speciilor de alge Chaetomorpha gracilis i Ch. aerea în procesul de epurare a apelor reziduale ........... 13 MARDARI (POPA) LOREDANA – Contribuii la studiul comunitilor de licheni saxicoli din Munii Bistriei (Carpaii Orientali) ....................................................................... 19 CIOCÂRLAN VASILE – Lathyrus linifolius (Reichard) Bässler în flora României ............... 25 CIOCÂRLAN VASILE – Îndreptarea unor erori existente în exsiccatele româneti .............. 27 CIOCÂRLAN VASILE – Specii eronat introduse în flora României ...................................... 29 SÎRBU CULI, OPREA ADRIAN – Plante adventive în Munii Stânioara (Carpaii Orientali – România) .................................................................................................... 33 OPREA ADRIAN, SÎRBU CULI – Plante rare în Munii Stânioara (Carpaii Orientali) ...... 47 MARDARI CONSTANTIN – Aspecte ale diversitii floristice în bazinul hidrografic al Negrei Brotenilor (Carpaii Orientali) -

Cytogenetic Research Regarding Species with Ornamental Value Identified in the North-East Area of Romania

CYTOGENETIC RESEARCH REGARDING SPECIES WITH ORNAMENTAL VALUE Cercetări Agronomice în Moldova Vol. XLIII , No. 4 (144) / 2010 CYTOGENETIC RESEARCH REGARDING SPECIES WITH ORNAMENTAL VALUE IDENTIFIED IN THE NORTH-EAST AREA OF ROMANIA Lucia DRAGHIA*, Aliona MORARIU, Liliana CHELARIU University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Iaşi Received June 15, 2010 ABSTRACT - In the paper are presented existence of diploid and tetraploid data regarding the number of somatic populations, separated by geography and chromosome determine at three species of ecology. Population of Dianthus armeria, plants with ornamental value from identified in Iai area (Bîrnova forest), is a spontaneous flora of Romania (Allium mixt population with x=15, formed by ursinum L., Centaurea phrygia L., Dianthus tetraploid individuals 4n=60, but in which armeria L.) and cultivated in the could be found also a minor diploid experimental field to evaluate the adapt cytotype with chromosome number 2n=30. capacity, aiming to use them in crops. For chromosome study was used a root tip Key words: Allium ursinum; Centaurea meristem obtained from plantlets aged 3-7 Phrygia; Dianthus armeria; Chromosome days. Chromosome was stained by Feulghen number. method, and the samples were examined at optic microscope Motic, relevant images REZUMAT - Cercetări citogenetice la being assumed by a video camera and specii cu valoare ornamentală, processed with its soft. The obtained results identificate în zona de nord-est a were compared with the ones already României. În lucrare sunt prezentate date cu existed in the literature, at populations from privire la numărul cromozomilor somatici, other ecologic and geographic areas. So at determinat la trei specii de plante cu valoare Allium ursinum, from Dobrovăţ forest (Iaşi ornamentală, provenite din flora spontană a area) all the analysed individuals had a României (Allium ursinum L., Centaurea chromosome number 2n=2x=14, specie phrygia L., Dianthus armeria L.) şi being characterized by a great karyological cultivate în câmpul experimental pentru stability. -

Compositae Newsletter 2, 1975) Have at Last Been Published As Heywood, V.H., Harborne, J.B

ft Ml ' fft'-A Lb!V CCMPCSIT4E # NEWSLETTER Number Six June 1978 Charles Jeffrey, Editor, Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, U.K. Financial support of the NEWSLETTER is generously provided by Otto Koeltz Antiquariat, P.O. Box I36O, 624 Koenigstein-Taunus, B.R.D. EDITORIAL The proceedings of the Reading Symposium (Compositae Newsletter 2, 1975) have at last been published as Heywood, V.H., Harborne, J.B. & Turner, B.L. (eds.), The Biology and Chemistry of the Compositae , Academic Press, London, New York and San Francisco , 1978, price £55 (#107.50)* In conjunction with the papers by Carlquist, S., Tribal Interrelationships and Phylogeny of the Asteraceae (Aliso 8: 446-492, 1976), Cronquist, A., The " Compositae Revisited (Brittonia 29: 137-153, 1977) and Wagenits, G. t Systematics and Phylogeny of the Compositae (PI. Syst. Evol. 125: 29-46, 1976), it gives the first overall review of the family since Bentham's time. On the evidence provided, the infrafamilial classification proposed by Wagenitz is most strongly supported, to which that proposed by Carlquist is very similar, except for his placing of the Eupatorieae in the Cichorioideae instead of the Asteroideae . In the previous Newsletter, a list of workers on Compositae and their research projects was published. New and revised entries to this list are welcomed by the editor; please provide your name, institution, institutional address, new or current research projects, recent publications, intended expeditions and study visits, and any requests for material or information. Articles, book reviews, notices of meetings, and any news from individuals or institutions that may be useful to synantherologists anywhere are also invited. -

Dissertation / Doctoral Thesis

DISSERTATION / DOCTORAL THESIS Titel der Dissertation /Title of the Doctoral Thesis „ Forecasting Plant Invasions in Europe: Effects of Species Traits, Horticultural Use and Climate Change. “ verfasst von / submitted by Günther Klonner, BSc MSc angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Wien, 2017 / Vienna 2017 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 794 685 437 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt / Biologie field of study as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Stefan Dullinger “Whatever makes the past, the distant, or the future, predominate over the present, advances us in the dignity of thinking beings.” Samuel Johnson (1791) “In the 1950s, the planet still had isolated islands, in both geographical and cultural terms - lands of unique mysteries, societies, and resources. By the end of the 20th century, expanding numbers of people, powerful technology, and economic demands had linked Earth’s formerly isolated, relatively non-industrialized places with highly developed ones into an expansive and complex network of ideas, materials, and wealth.” Lutz Warren and Kieffer (2010) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT As for many others, the last few years have been an up and down, however, I made it through thanks to my family, friends and colleagues without whom this wouldn’t have been possible. To the love of my life, my wife Christine Schönberger: because you are my support, advice and courage. Because we share the same dreams. Many Thanks! My brother and one of my best friends, Dietmar, who provided me through emotional support in many situations and shares my love to mountains and sports: Thank you! I am also grateful to my other family members, especially my parents Ingeborg and Martin, who were always keen to know what I was doing and how I was proceeding. -

Evolution of the Centaurea Acrolophus Subgroup

Evolution of the Centaurea Acrolophus subgroup [Evolució del subgrup Acrolophus del gènere Centaurea] Andreas Hilpold ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. En la utilización o cita de partes de la tesis es obligado indicar el nombre de la persona autora. -

Latin for Gardeners: Over 3,000 Plant Names Explained and Explored

L ATIN for GARDENERS ACANTHUS bear’s breeches Lorraine Harrison is the author of several books, including Inspiring Sussex Gardeners, The Shaker Book of the Garden, How to Read Gardens, and A Potted History of Vegetables: A Kitchen Cornucopia. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 © 2012 Quid Publishing Conceived, designed and produced by Quid Publishing Level 4, Sheridan House 114 Western Road Hove BN3 1DD England Designed by Lindsey Johns All rights reserved. Published 2012. Printed in China 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00919-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00922-3 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Lorraine. Latin for gardeners : over 3,000 plant names explained and explored / Lorraine Harrison. pages ; cm ISBN 978-0-226-00919-3 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN (invalid) 978-0-226-00922-3 (e-book) 1. Latin language—Etymology—Names—Dictionaries. 2. Latin language—Technical Latin—Dictionaries. 3. Plants—Nomenclature—Dictionaries—Latin. 4. Plants—History. I. Title. PA2387.H37 2012 580.1’4—dc23 2012020837 ∞ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). L ATIN for GARDENERS Over 3,000 Plant Names Explained and Explored LORRAINE HARRISON The University of Chicago Press Contents Preface 6 How to Use This Book 8 A Short History of Botanical Latin 9 Jasminum, Botanical Latin for Beginners 10 jasmine (p. 116) An Introduction to the A–Z Listings 13 THE A-Z LISTINGS OF LatIN PlaNT NAMES A from a- to azureus 14 B from babylonicus to byzantinus 37 C from cacaliifolius to cytisoides 45 D from dactyliferus to dyerianum 69 E from e- to eyriesii 79 F from fabaceus to futilis 85 G from gaditanus to gymnocarpus 94 H from haastii to hystrix 102 I from ibericus to ixocarpus 109 J from jacobaeus to juvenilis 115 K from kamtschaticus to kurdicus 117 L from labiatus to lysimachioides 118 Tropaeolum majus, M from macedonicus to myrtifolius 129 nasturtium (p.