Evolution of the Centaurea Acrolophus Subgroup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

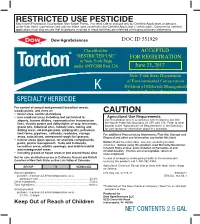

Caution Restricted Use Pesticide

RESTRICTED USE PESTICIDE May Injure (Phytotoxic) Susceptible, Non-Target Plants. For retail sale to and use only by Certified Applicators or persons under their direct supervision and only for those uses covered by the Certified Applicator's certification. Commercial certified applicators must also ensure that all persons involved in these activities are informed of the precautionary statements. DOC ID 551929 June 23, 2017 For control of annual and perennial broadleaf weeds, woody plants, and vines on CAUTION • forest sites, conifer plantations • non-cropland areas including, but not limited to, Agricultural Use Requirements airports, barrow ditches, communication transmission Use this product only in accordance with its labeling and with lines, electric power and utility rights-of-way, fencerows, the Worker Protection Standard, 40 CFR part 170. Refer to label gravel pits, industrial sites, military sites, mining and booklet under "Agricultural Use Requirements" in the Directions drilling areas, oil and gas pads, parking lots, petroleum for Use section for information about this standard. tank farms, pipelines, railroads, roadsides, storage For additional Precautionary Statements, First Aid, Storage and areas, substations, unimproved rough turf grasses, Disposal and other use information see inside this label. • natural areas (open space), for example campgrounds, parks, prairie management, trails and trailheads, Notice: Read the entire label. Use only according to label recreation areas, wildlife openings, and wildlife habitat directions. Before using this product, read Warranty Disclaimer, Inherent Risks of Use, and Limitation of Remedies at end and management areas of label booklet. If terms are unacceptable, return at • including grazed or hayed areas in and around these sites once unopened. -

THESE Hanène ZATER

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UNIVERSITE FRÈRES MENTOURI CONSTANTINE FACULTE DES SCIENCES EXACTES DEPARTEMENT DE CHIMIE N° d’ordre :168/DS/2017 Série :25/CH/2017 . THESE Présentée en vue de l’obtention du diplôme de Doctorat en Sciences Spécialité : Chimie Organique Option : Phytochimie Par Hanène ZATER Constituants chimiques, propriétés cytotoxiques, antifongiques et antibactériennes de l’extrait chloroforme de Centaurea diluta Ait. subsp. algeriensis (Coss. & Dur.) Maire Devant le jury : Pr. BENAYACHE Samir Université Frères Mentouri, Constantine Président Pr. BENAYACHE Fadila Université Frères Mentouri, Constantine Directrice de thèse, Rapporteur Pr. AMEDDAH Souad Université Frères Mentouri, Constantine Examinateur Pr. LEGSEIR Belgacem Université Badji Mokhtar, Annaba Examinateur Pr. BOUDJERDA Université Mohamed Seddik Examinateur Azzeddine Benyahia, Jijel Pr. KHELILI Smail Université Mohamed Seddik Benyahia, Examinateur Jijel 15/07/ 2017 ۞بِ ْس ِم هَّللاِ ال هر ْح َم ِن ال هر ِحي ِم ۞ ۞ ُس ْب َحانَ َك ََل ِع ْل َم لَنَا إِ هَل َما َعله ْمتَنَا ۖ إِنه َك أَ ْن َت ا ْل َعلِي ُم ا ْل َح ِكي ُم ۞ ﴿ ص َد َق آهلل العل ٌي آلعظ ْيم﴾ Dédicaces ♥A L’âme de ma grande -mère & mon grand-père &Ami Djamel… ♥A mes chers parents Akila & Abderrazek … ♥A mes chères sœurs : Amel, Ibtissem, Schehra, Lamia, Faiza Mouna ♥ A mon frère Ahmed Souheil. ♥A mes neveux. ♥A mes oncles & tantes… ♥ A tous mes amis & collègues !!! ♥ A tous ceux qui ont contribué un jour à mon éducation !!! Je dédie ce modeste travail. Hanène Remerciements En préambule, je souhaite rendre grâce au bon Dieu « ALLAH », le Clément et Miséricordieux de m’avoir donné la force, le courage et la patience de mener à bien ce modeste travail. -

Taksonomska I Korološka Analiza Roda Centaurea L. U Herbariju Ive I Marije Horvat (ZAHO)

Taksonomska i korološka analiza roda Centaurea L. u Herbariju Ive i Marije Horvat (ZAHO) Uremović, Sanja Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:945197 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-10 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU Prirodoslovno – matematiĉki fakultet BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK Sanja Uremović Taksonomska i korološka analiza roda Centaurea L. u Herbariju Ive i Marije Horvat (ZAHO) Diplomski rad Zagreb, 2011. SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU Prirodoslovno – matematiĉki fakultet BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK Sanja Uremović Taksonomska i korološka analiza roda Centaurea L. u Herbariju Ive i Marije Horvat (ZAHO) Diplomski rad Zagreb, 2011. Ovaj diplomski rad izrađen je na Botaničkom zavodu Prirodoslovno – matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu pod voditeljstvom prof.dr.sc. Božene Mitić, radi stjecanja zvanja profesor biologije i kemije. Zahvala Tijekom izrade ovog diplomskog rada pruţena mi je velika pomoć, struĉni savjeti te razumijevanje od strane mentorice prof. dr. sc. Boţene Mitić, kojoj se najljepše zahvaljujem. TakoĊer, doc. dr. sc. Igoru Boršiću i doc. dr. sc. Sandru Bogdanoviću veliko hvala na bezrezervnoj pomoći, na brojnim struĉnim savjetima, strpljenju i potpori tijekom izrade ovog rada. Hvala Margeriti, Mariji, Ţeljki, Tamari i Nives na savjetima, nesebiĉnom razumijevanju i podršci, ne samo tijekom izrade ovog diplomskog rada, nego i tijekom studiranja. Konaĉno, za moju obitelj ne postoji dovoljno veliko hvala za svu podršku, strpljenje, razumijevanje i sve što su uĉinili za mene, no ipak, mama, tata, seka, Vjeko – hvala vam što ste uvijek uz mene. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Weed Risk Assessment: Centaurea Calcitrapa

Weed Risk Assessment: Centaurea calcitrapa 1. Plant Details Taxonomy: Centaurea calcitrapa L. Family Asteraceae. Common names: star thistle, purple star thistle, red star thistle. Origins: Native to Europe (Hungary, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Russian Federation, Ukraine, Albania, Greece, Italy, Romania, Yugoslavia, France, Portugal, Spain), Macaronesia (Canary Islands, Madeira Islands), temperate Asia (Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey) and North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia) (GRIN database). Naturalised Distribution: Naturalised in New Zealand, South Africa, Central America, South America, the United States of America (eg. naturalised in 14 states, mostly in northwest including California, Idaho, Washington, Wyoming, New Mexico, Oregon, Arizona) (USDA plants database), and Australia (GRIN database). Description: C. calcitrapa is an erect, bushy and spiny biannual herb that is sometimes behaves as an annual or short-lived perennial. It grows to 1 m tall. Young stems and leaves have fine, cobweb-like hairs that fall off over time. Older stems are much-branched, straggly, woody, sparsely hairy, without wings or spines and whitish to pale green. Lower leaves are deeply divided while upper leaves are generally narrow and undivided. Rosette leaves are deeply divided and older rosettes have a circle of spines in the centre. This is the initial, infertile, flower head. Numerous flowers are produced on the true flowering stem and vary from lavender to a deep purple colour. Bracts end in a sharp, rigid white to yellow spines. Seed is straw coloured and blotched with dark brown spots. The pappus is reduced or absent. Bristles are absent. Seeds are 3-4mm long, smooth and ovoid. The root is a fleshy taproot (Parsons and Cuthbertson, 2001) (Moser, L. -

Asteraceae) from Different Italian Islands

Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat., Mem., Serie B, 121 (2014) pagg. 93-100, tab. 1; doi: 10.2424/ASTSN.M.2014.07 LUCIA VIEGI (*), ROBERTA VANGEliSTI (**), ROBERTO CECOTTI (***), ALDO TAVA (***) ESSENTIAL OIL COMPOSITION OF SOME CENTAUREA SP. (ASTERACEAE) FROM DIFFERENT ITALIAN ISLANDS Abstract - Essential oil composition of some Centaurea sp. (Asteraceae) subsp. umbrosa (Fiori) Greuter, C. panormitana Lojac. subsp. todaroi from different italian islands. The volatile constituents of leaves and (Lacaita) Greuter, C. panormitana Lojac. subsp. seguenzae (Lacaita) flower heads of several Centaurea species from different islands of Greuter da diverse località della Sicilia. La resa in olio essenziale è Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Sea were investigated for the first time. C. risultata essere compresa tra 0.02 e 0.13% per le foglie e tra 0.01 e veneris (Sommier) Bég. from Palmaria Island (Ligurian Sea), C. gym- 0.09% per le infiorescenze, calcolata sul peso fresco. Gli estratti sono nocarpa Moris & De Not. from Capraia Island, C. aetaliae (Somm.) stati quindi analizzati mediante GC/FID e GC/MS e più di 100 com- Bég. and C. ilvensis (Sommier) Arrigoni from Elba Island (Northern posti appartenenti a diverse classi chimiche sono stati identificati e Tyrrhenian Sea); C. aeolica Lojac. subsp. aeolica from Lipari, Aeolian quantificati. I sesquiterpeni rappresentano la classe più abbondante Islands, C. busambarensis Guss., C. panormitana Lojac. subsp. ucriae di composti (valutati rispettivamente 22.35-61.67% e 35.16-57.51% (Lacaita) Greuter, C. panormitana Lojac. subsp. umbrosa (Fiori) Greu- dei volatili totali in foglie ed infiorescenze), tra cui il germacrene D ter, C. panormitana Lojac. subsp. -

Thistle Identification Referee 2017

Thistle Identification Referee 2017 Welcome to the Thistle Identification Referee. The purpose of the referee is to review morphological characters that are useful for identification of thistle and knapweed fruits, as well as review useful resources for making decisions on identification and classification of species as noxious weed seeds. Using the Identification Guide for Some Common and Noxious Thistle and Knapweed Fruits (Meyer 2017) and other references of your choosing, please answer the questions below (most are multiple choice). Use the last page of this document as your answer sheet for the questions. Please send your answer sheet to Deborah Meyer via email ([email protected]) by May 26, 2017. Be sure to fill in your name, lab name, and email address on the answer sheet to receive CE credit. 1. In the Asteraceae, the pappus represents this floral structure: a. Modified stigma b. Modified corolla c. Modified calyx d. Modified perianth 2. Which of the following species has an epappose fruit? a. Centaurea calcitrapa b. Cirsium vulgare c. Onopordum acaulon d. Cynara cardunculus 3. Which of the following genera has a pappus comprised of plumose bristles? a. Centaurea b. Carduus c. Silybum d. Cirsium 4. Which of the following species has the largest fruits? a. Cirsium arvense b. Cirsium japonicum c. Cirsium undulatum d. Cirsium vulgare 5. Which of the following species has a pappus that hides the style base? a. Volutaria muricata b. Mantisalca salmantica c. Centaurea solstitialis d. Crupina vulgaris 6. Which of the following species is classified as a noxious weed seed somewhere in the United States? a. -

Carthamus Tinctorius) and Wild Relatives of the Genus Carthamus Marion Mayerhofer1, Reinhold Mayerhofer1, Deborah Topinka2, Jed Christianson1, Allen G Good1*

Mayerhofer et al. BMC Plant Biology 2011, 11:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2229/11/47 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Introgression potential between safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) and wild relatives of the genus Carthamus Marion Mayerhofer1, Reinhold Mayerhofer1, Deborah Topinka2, Jed Christianson1, Allen G Good1* Abstract Background: Safflower, Carthamus tinctorius, is a thistle that is grown commercially for the production of oil and birdseed and recently, as a host for the production of transgenic pharmaceutical proteins. C. tinctorius can cross with a number of its wild relatives, creating the possibility of gene flow from safflower to weedy species. In this study we looked at the introgression potential between different members of the genus Carthamus, measured the fitness of the parents versus the F1 hybrids, followed the segregation of a specific transgene in the progeny and tried to identify traits important for adaptation to different environments. Results: Safflower hybridized and produced viable offspring with members of the section Carthamus and species with chromosome numbers of n = 10 and n = 22, but not with n = 32. The T-DNA construct of a transgenic C. tinctorius line was passed on to the F1 progeny in a Mendelian fashion, except in one specific cross, where it was deleted at a frequency of approximately 21%. Analyzing fitness and key morphological traits like colored seeds, shattering seed heads and the presence of a pappus, we found no evidence of hybrid vigour or increased weediness in the F1 hybrids of commercial safflower and its wild relatives. Conclusion: Our results suggest that hybridization between commercial safflower and its wild relatives, while feasible in most cases we studied, does not generate progeny with higher propensity for weediness. -

Centaurea Sect

Tesis Doctoral ESTUDIO TAXONÓMICO DE CENTAUREA SECT. SERIDIA (JUSS.) DC. (ASTERACEAE) EN LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA E ISLAS BALEARES Memoria presentada por Dña. Vanessa Rodríguez Invernón para optar al grado de Doctor en Ciencias Biológicas por la Universidad de Córdoba Director de Tesis: Prof. Juan Antonio Devesa 15 de octubre de 2013 TITULO: Estudio taxonómico de Centaurea Sect. Seridia (Juss.) DC. en la Península Ibérica e Islas Baleares AUTOR: Vanessa Rodríguez Invernón © Edita: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba. 2013 Campus de Rabanales Ctra. Nacional IV, Km. 396 A 14071 Córdoba www.uco.es/publicaciones [email protected] rírulo DE LA TESIS: Estudio Taxonómico de centaurea sect. seridia (Juss.) DG. en la Península lbérica e Islas Baleares DOCTORANDO/A: VANESSA RODRíGUEZ INVERNÓN INFORME RAZONADO DEL/DE LOS DIRECTOR/ES DE LA TESIS (se hará mención a la evolución y desarrollo de la tesis, así como a trabajos y publicaciones derivados de la misma). El objeto de esta Tesis Doctoral ha sido el estudio taxonómico del género Centaurea, cuya diversidad y complejidad en el territorio es alta, por lo que se ha restringido a la sección Seridia (Juss.) DC. y, atin así, el estudio ha requerido 4 años de dedicación para su finalización. La iniciativa se inscribe en el Proyecto Flora iberica, financiado en la actualidad por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad. El estudio ha entrañado la realización de numerosas prospecciones en el campo, necesarias para poder abordar aspectos importantes, tales como los estudios cariológicos, palinológicos y moleculares, todos encaminados a apoyar la slntesis taxonómica, que ha requerido además de un exhaustivo estudio de material conservado en herbarios nacionales e internacionales. -

Conservation Assessment of the Endemic Plants of the Tuscan Archipelago, Italy

Conservation assessment of the endemic plants of the Tuscan Archipelago, Italy B RUNO F OGGI,DANIELE V ICIANI,RICCARDO M. BALDINI A NGELINO C ARTA and T OMMASO G UIDI Abstract The Mediterranean islands support a rich di- Circa 25,000 species are native to the region, with a high versity of flora, with a high percentage of endemic species. percentage of endemism (50–59%: Greuter, 1991; Médail We used the IUCN categories and criteria to assess the & Quèzel, 1997), and the archipelagos of the Mediterranean conservation status of 16 endemic plant taxa (species and are thus a natural laboratory for evolutionary studies subspecies) of the Tuscan Archipelago, based on data (Thompson, 1999). collected during field surveys over 4 years. Our data were A taxon is considered endemic when its distribution sufficient to use criteria B, C and D in our assessment. We is circumscribed to a well-defined geographical district used criterion B in the assessment of all 16 taxa, criterion C (Anderson, 1994; Cuttelod et al., 2008). Endemic taxa may for four taxa, criterion D for 11 taxa and criteria B, C and be defined as rare and potentially threatened (Ellstrand & D for three taxa, Centaurea gymnocarpa, Limonium doriae Elam, 1993; Fjeldså, 1994; Linder, 1995; Ceballos et al., 1998; and Silene capraria. According to our results L. doriae, Myers et al., 2000;Işik, 2011), and therefore they may be Romulea insularis and S. capraria are categorized as considered conservation priorities (Schnittler & Ludwig, Critically Endangered and therefore require immediate 1996; Gruttke et al., 1999). Populations of many species conservation measures; eight taxa are categorized as have declined (Butchart et al., 2010; SCBD, 2010) and Endangered, two as Vulnerable and three as Near extinction rates exceed background extinction rates by two Threatened. -

Nuclear and Plastid DNA Phylogeny of the Tribe Cardueae (Compositae

1 Nuclear and plastid DNA phylogeny of the tribe Cardueae 2 (Compositae) with Hyb-Seq data: A new subtribal classification and a 3 temporal framework for the origin of the tribe and the subtribes 4 5 Sonia Herrando-Morairaa,*, Juan Antonio Callejab, Mercè Galbany-Casalsb, Núria Garcia-Jacasa, Jian- 6 Quan Liuc, Javier López-Alvaradob, Jordi López-Pujola, Jennifer R. Mandeld, Noemí Montes-Morenoa, 7 Cristina Roquetb,e, Llorenç Sáezb, Alexander Sennikovf, Alfonso Susannaa, Roser Vilatersanaa 8 9 a Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 10 b Systematics and Evolution of Vascular Plants (UAB) – Associated Unit to CSIC, Departament de 11 Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Facultat de Biociències, Universitat Autònoma de 12 Barcelona, ES-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 13 c Key Laboratory for Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, 14 Chengdu, China 15 d Department of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152, USA 16 e Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Univ. Savoie Mont Blanc, CNRS, LECA (Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine), FR- 17 38000 Grenoble, France 18 f Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, 19 Finland; and Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 20 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia 21 22 *Corresponding author at: Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s. n., ES- 23 08038 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Herrando-Moraira). 24 25 Abstract 26 Classification of the tribe Cardueae in natural subtribes has always been a challenge due to the lack of 27 support of some critical branches in previous phylogenies based on traditional Sanger markers. -

A Common Threat to IUCN Red-Listed Vascular Plants in Europe

Tourism and recreation: a common threat to IUCN red-listed vascular plants in Europe Author Ballantyne, Mark, Pickering, Catherine Marina Published 2013 Journal Title Biodiversity and Conservation DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0569-2 Copyright Statement © 2013 Springer. This is an electronic version of an article published in Biodiversity and Conservation, December 2013, Volume 22, Issue 13-14, pp 3027-3044. Biodiversity and Conservation is available online at: http://link.springer.com/ with the open URL of your article. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/55792 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Manuscript 1 Tourism and recreation: a common threat to IUCN red-listed vascular 1 2 3 4 2 plants in Europe 5 6 7 8 3 *Mark Ballantyne and Catherine Marina Pickering 9 10 11 12 4 Environmental Futures Centre, School of Environment, Griffith University, Gold Coast, 13 14 5 Queensland 4222, Australia 15 16 17 18 6 *Corresponding author email: [email protected], telephone: +61(0)405783604 19 20 21 7 22 23 8 24 25 9 26 27 28 10 29 30 11 31 32 12 33 34 13 35 36 37 14 38 39 15 40 41 16 42 43 17 44 45 46 18 47 48 19 49 50 20 51 52 21 53 54 55 22 56 57 23 58 59 24 60 61 62 63 64 65 25 Abstract 1 2 3 4 26 Tourism and recreation are large industries employing millions of people and contribute over 5 6 27 US$2.01 trillion to the global economy.