Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Programs – Total Canada (English)

Top Programs – Total Canada (English) February 22, 2021 - February 28, 2021 Based on confirmed program schedules and final audience data including 7-day playback, Demographic: All Persons 2+ Total 2+ Rank Program Broadcast Outlet Weekday Start End # Aired AMA(000) 1 THE GOOD DOCTOR CTV Total M...... 22:00 23:00 1 2173 2 9-1-1: LONE STAR CTV Total M...... 21:01 22:00 1 2148 3 9-1-1 Global Total M...... 20:00 21:00 1 2058 4 THE GOLDEN GLOBES CTV Total ......S 20:00 23:04 1 1784 5 YOUNG SHELDON CTV Total ...T... 20:00 20:31 1 1752 6 THE ROOKIE CTV Total ......S 19:00 20:00 1 1579 7 CTV EVENING NEWS CTV Total MTWTF.. 17:59 19:00 5 1569 8 THE EQUALIZER Global Total ......S 20:00 21:00 1 1532 9 NHL HOCKEY-LEAFS Sportsnet National+ ..W.... 19:12 21:37 1 1358 10 THIS IS US CTV Total .T..... 21:00 22:00 1 1336 11 CALL ME KAT CTV Total ...T... 21:00 21:30 1 1313 12 B POSITIVE CTV Total ...T... 20:31 21:00 1 1255 13 CTV EVENING NEWS WEEKEND CTV Total .....SS 18:00 19:00 2 1193 14 SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE Global Total .....S. 23:29 01:02 1 1178 15 THE CONNERS CTV Total ..W.... 21:00 21:30 1 1177 16 BULL Global Total M...... 22:00 23:00 1 1166 17 LAW & ORDER: SVU CTV Total ...T... 22:00 23:00 1 1118 18 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Global Total ......S 22:00 23:00 1 1076 18 CTV NATIONAL NEWS CTV Total MTWTFSS 23:00 23:30 7 1076 20 NCIS: LOS ANGELES Global Total ......S 21:00 22:00 1 1063 21 CLARICE Global Total ...T.. -

THE UNITED STATES and SOUTH AFRICA in the NIXON YEARS by Eric J. Morgan This Thesis Examines Relat

ABSTRACT THE SIN OF OMISSION: THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA IN THE NIXON YEARS by Eric J. Morgan This thesis examines relations between the United States and South Africa during Richard Nixon’s first presidential administration. While South Africa was not crucial to Nixon’s foreign policy, the racially-divided nation offered the United States a stabile economic partner and ally against communism on the otherwise chaotic post-colonial African continent. Nixon strengthened relations with the white minority government by quietly lifting sanctions, increasing economic and cultural ties, and improving communications between Washington and Pretoria. However, while Nixon’s policy was shortsighted and hypocritical, the Afrikaner government remained suspicious, believing that the Nixon administration continued to interfere in South Africa’s domestic affairs despite its new policy relaxations. The Nixon administration concluded that change in South Africa could only be achieved through the Afrikaner government, and therefore ignored black South Africans. Nixon’s indifference strengthened apartheid and hindered liberation efforts, helping to delay black South African freedom for nearly two decades beyond his presidency. THE SIN OF OMMISSION: THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA IN THE NIXON YEARS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Eric J. Morgan Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor __________________________________ (Dr. Jeffrey P. Kimball) Reader ___________________________________ (Dr. Allan M. Winkler) Reader ___________________________________ (Dr. Osaak Olumwullah) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . iii Prologue The Wonderful Tar Baby Story . 1 Chapter One The Unmovable Monolith . 3 Chapter Two Foresight and Folly . -

TV Listings Aug21-28

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 21, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Stand Up to Cancer (N) NCIS: New Orleans ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ Grace Paid Prog. ThisMinute 5 5Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ 1st Look In Touch Hollywood 6 6Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Chicago Fire FC at Orlando City SC. Weekend News WGN News GN Sports Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Lawrence Welk’s TV Great Performances ’ This Land Is Your Land (My Music) Bee Gees: One Night Only ’ Agatha and Murders 11 Father Brown ’ Shakespeare Death in Paradise ’ Professor T Unforgotten Rick Steves: The Alps ’ 12 12 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Skin Care 24 24 High School Football Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 WNBA Basketball: Lynx at Sky Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ News Flannery Game of Talents ’ Bensinger TMZ (N) ’ PiYo Wor. -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

Ipi Congress Report 2

SALZBURG IPI CONGRESS REPORT 2www.freemedia.at003 IPI WORLD CONGRESS & 52nd GENERAL ASSEMBLY IPI Congress Report CONTENTS Programme ................................................ 1 Editorial........................................................ 4 Opening Ceremony .............................. 6 Pluralism, Democracy and the Clash of Civilisations ................14 INTERNATIONAL Analysing the World Summit PRESS INSTITUTE on the Information Society............ 24 Chairman SARS and the Media ........................ 30 Jorge E. Fascetto Chairman of the Board, Diario el Día La Plata, Argentina IPI Free Media Pioneer 2003 ...... 38 Director Congress Snapshots ........................ 40 Johann P. Fritz Media in War Zones Congress Coordinator and and Regions of Conflict .................. 42 Editor, IPI Congress Report Michael Kudlak The International News Safety Institute........................ 52 Assistant Congress Coordinator Christiane Klint Media Self-Regulation: A Press Freedom Issue .................. 56 Congress Transcripts Rita Klint The Transatlantic Rift ........................ 64 International Press Institute (IPI) The Oslo Accords Spiegelgasse 2/29, A-1010 Vienna, Austria – 10 Years On........................................ 74 Tel: +43-1-512 90 11, Fax: +43-1-512 90 14 E-mail: [email protected], http://www.freemedia.at Farewell Remarks................................ 77 Cover Photograph: Tourismus Salzburg GmbH • Layout: Nik Bauer Printing kindly sponsored by Heidelberger Druckmaschinen Osteuropa Vertriebs-GmbH Paper kindly -

The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America 1

More The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America ROBERT M. COLLINS 1 2000 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2000 Published by Oxford All rights reserved. No by Robert M. University Press, Inc. part of this publication Collins 198 Madison Avenue, may be reproduced, New York, New York stored in a retrieval 10016. system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, Oxford is a registered mechanical, trademark of Oxford photocopying, recording, University Press. or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging–in–Publication Data Collins, Robert M. More : the politics of economic growth in postwar America / Robert M. Collins. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–19–504646–3 1. Wealth—United States—History—20th century. 2. United States—Economic policy. 3. United States—Economic conditions—1945–. 4. Liberalism—United States— History—20th Century. 5. National characteristics, American. I. Title. HC110.W4C65 2000 338.973—dc21 99–022524 Design by Adam B. Bohannon 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For My Parents Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Prologue: The Ambiguity of New Deal Economics 1 1 > The Emergence of Economic Growthmanship 17 2 > The Ascendancy of Growth Liberalism 40 3 > Growth Liberalism Comes a Cropper, 1968 68 4 > Richard Nixon’s Whig Growthmanship 98 5 > The Retreat from Growth in the 1970s 132 6 > The Reagan Revolution and Antistatist Growthmanship 166 7 > Slow Drilling in Hard Boards 214 Conclusion 233 Notes 241 Index 285 Preface bit of personal serendipity nearly three decades ago inspired this A book. -

The Search for the "Manchurian Candidate" the Cia and Mind Control

THE SEARCH FOR THE "MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE" THE CIA AND MIND CONTROL John Marks Allen Lane Allen Lane Penguin Books Ltd 17 Grosvenor Gardens London SW1 OBD First published in the U.S.A. by Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., and simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd, 1979 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 1979 Copyright <£> John Marks, 1979 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner ISBN 07139 12790 jj Printed in Great Britain by f Thomson Litho Ltd, East Kilbride, Scotland J For Barbara and Daniel AUTHOR'S NOTE This book has grown out of the 16,000 pages of documents that the CIA released to me under the Freedom of Information Act. Without these documents, the best investigative reporting in the world could not have produced a book, and the secrets of CIA mind-control work would have remained buried forever, as the men who knew them had always intended. From the documentary base, I was able to expand my knowledge through interviews and readings in the behavioral sciences. Neverthe- less, the final result is not the whole story of the CIA's attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent. I have done the best I can to make the book as accurate as possible, but I have been hampered by the refusal of most of the principal characters to be interviewed and by the CIA's destruction in 1973 of many of the key docu- ments. -

J. Edgar Hoover: the Man and the Secrets. Curt Gentry. Plume: New York, 1991

J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets. Curt Gentry. Plume: New York, 1991. P. 45 “Although Hoover’s memo did not explicitly state what should be kept in this file, ... they might also, and often did, include personal information, sometimes derogatory in nature ...” P. 51 “their contents [Hoover’s O/C files] included blackmail material on the patriarch of an American political dynasty, his sons, their wives, and other women; allegations of two homosexual arrests which Hoover leaked to help defeat a witty, urbane Democratic presidential candidate; the surveillance reports on one of America’s best-known first ladies and her alleged lovers, both male and female, white and black; the child-molestation documentation the director used to control and manipulate on of his Red-baiting proteges...” P. 214 “Even before [Frank] Murphy had been sworn in, Hoover had opened a file on his new boss. It was not without derogatory information. Like Hoover, Murphy was a lifelong bachelor . the former Michigan governor was a ‘notorious womanizer’.” P. 262 “Hoover believed that the morality of America was his business . ghost-written articles warning the public about the dangers of motels and drive-in ‘passion-pits’.” P. 302 “That the first lady [Eleanor Roosevelt] refused Secret Service protection convinced Hoover that she had something to hide. That she also maintained a secret apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village, where she was often visited by her friends but never by the president, served to reinforce the FBI director’s suspicions. What she was hiding, Hoover convinced himself, was a hyperactive sex life. -

OPC, Coalition Sign Pact to Boost Freelancer Safety

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • February 2015 OPC, Coalition Sign Pact to Boost Freelancer Safety By Emma Daly and the freelancers who Diane Foley, mother of the late are assuming an ever- freelance reporter James Foley, was greater burden in cover- guest of honor at a panel discussion ing dangerous stories, to launch “A Call for Global Safety the panelists see these Principles and Practices,” the first principles as a first step industry code of conduct to include toward greater responsi- media companies and freelancers bility and accountability in an attempt to reduce the risks to by both reporters on the those covering hazardous stories. ground and their editors. The guidelines were presented to an “I am deeply proud Rhon G. Flatts audience of journalists and students of the OPC and the OPC David Rohde of Reuters, left, and Marcus Mabry during two panel discussions held at Foundation’s part in this speak to students and media about a the Columbia University School of long overdue effort,” new industry code of conduct. Journalism’s Stabile Student Center Mabry said. Shehda Abu Afash in Gaza. on Feb. 12 and introduced by Dean Sennott flagged the horrific mur- By the launch on Thursday al- Steve Coll. der of Jim Foley as a crucial moment most 30 news and journalism orga- The first panel – David Rohde in focusing all our minds on the need nizations had signed on to the prin- of Reuters, OPC President Marcus to improve safety standards, despite ciples, including the OPC and OPC Mabry, Vaughan Smith of the Front- efforts over the past couple of de- Foundation, AFP, the AP, the BBC, line Freelance Register, John Dan- cades to introduce hostile environ- Global Post Guardian News and Me- iszewiski from the AP and Charlie ment and medical training, as well dia, PBS FRONTLINE and Thom- Sennott of the Ground Truth Project as protective equipment and more af- son Reuters. -

Introduction Rick Perlstein

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Rick Perlstein I In the fall of 1967 Richard Nixon, reintroducing himself to the public for his second run for the presidency of the United States, published two magazine articles simultaneously. The first ran in the distinguished quarterly Foreign Affairs, the re- view of the Council of Foreign Relations. “Asia after Viet Nam” was sweeping, scholarly, and high-minded, couched in the chessboard abstrac- tions of strategic studies. The intended audience, in whose language it spoke, was the nation’s elite, and liberal-leaning, opinion-makers. It argued for the diplomatic “long view” toward the nation, China, that he had spoken of only in terms of red- baiting demagoguery in the past: “we simply can- not afford to leave China forever outside the fam- ily of nations,” he wrote. This was the height of foreign policy sophistication, the kind of thing one heard in Ivy League faculty lounges and Brookings Institution seminars. For Nixon, the conclusion was the product of years of quiet travel, study, and reflection that his long stretch in the political wil- derness, since losing the California governor’s race in 1962, had liberated him to carry out. It bore no relation to the kind of rip-roaring, elite- baiting things he usually said about Communists For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. -

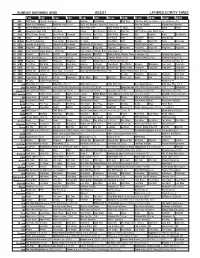

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

The Frederick, MD, News‐Post and the Bruce Ivins Story Teaching Note

CSJ‐ 09‐ 0015.3 PO Privacy and the Public Interest: the Frederick, MD, News‐Post and the Bruce Ivins Story Teaching Note Case Summary Journalists frequently enter the private world of individuals, their friends, family and colleagues in order to tell a story. Often, these subjects of the news participate willingly, and are keen to share their thoughts and feelings with a wider audience. But that is not always the case. Some people are uncomfortable in the media spotlight, especially if they are “private” figures unaccustomed to such a glare, or linked to scandal and reluctant to participate in what they see as a “trial by media.” Consequently, they may shun involvement. In such cases, media outlets must make judgment calls that take into account a range of interests, including their need to tell credible, interesting stories that compete with rival news organizations; the subject’s rights and wishes to retain privacy; and the public’s right to know. This case study focuses on the Frederick News‐Post, a local Maryland newspaper, and its struggle to balance such issues in its coverage of a local scientist suspected of mailing several deadly anthrax‐filled letters after the September 11, 2001, terror attacks. Microbiologist Bruce Ivins, an anthrax expert, was the latest in a string of FBI suspects and faced arrest when he committed suicide in July 2008. Like other media, the News‐Post learned about the Ivins investigation only after his death, and regarded the FBI’s claims with skepticism given its previous wrongful accusations, and an embarrassing press history of rushing to judgment in cases where suspects were later vindicated.