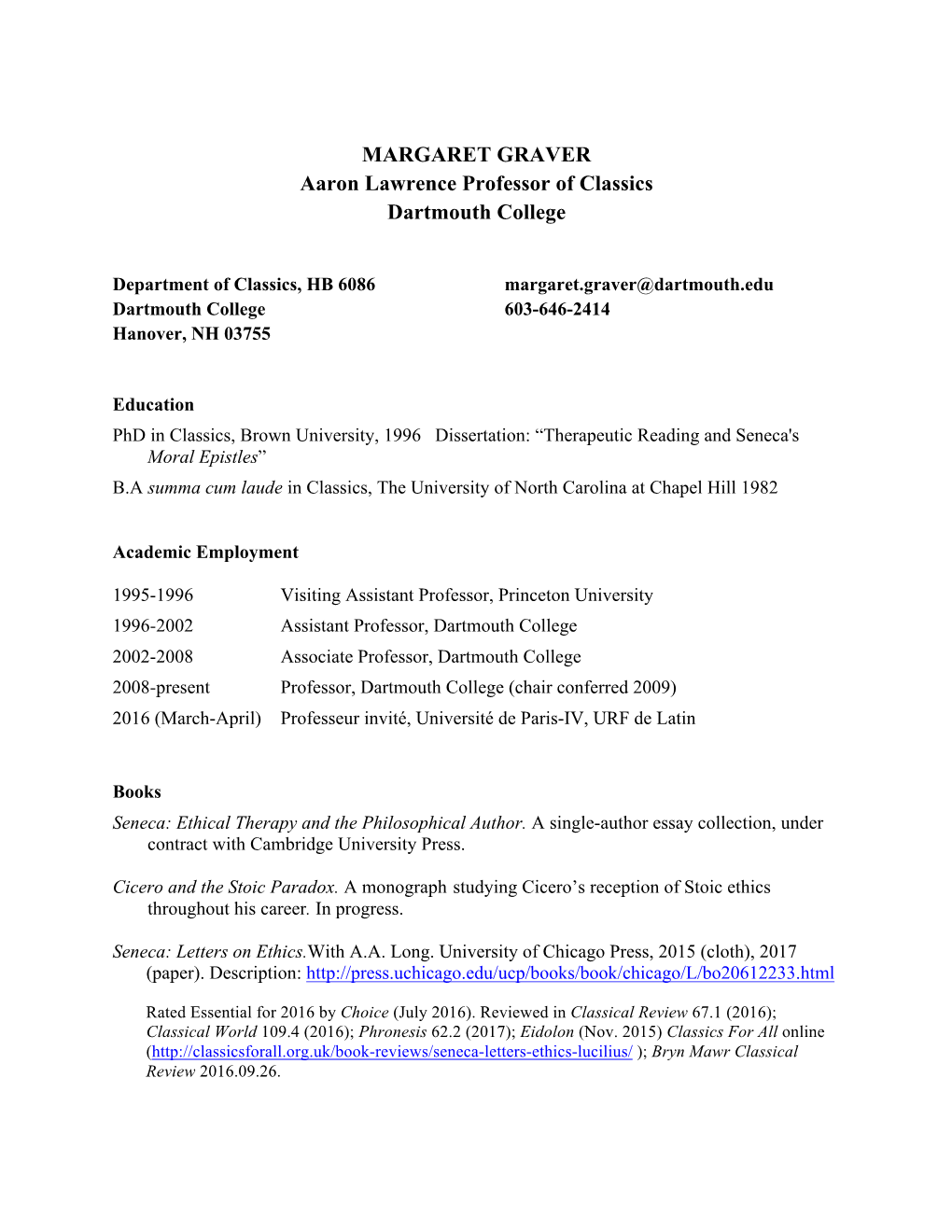

MARGARET GRAVER Aaron Lawrence Professor of Classics Dartmouth College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cicero on the Gods and Roman Religious Practices

Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica 23(2): 303–313 Cicero on the gods and Roman religious practices Arina BRAGOVA1 Abstract. The article analyses Cicero’s attitude to gods, religion, divination, and superstition. Cicero follows tradition in acknowledging the existence of the gods, considering them immortal, blissful, animate, and anthropomorphic. He is ambivalent about the interaction between the gods and people. Cicero considers religion important for the Roman people because this was the popular belief — it was not his own viewpoint. Cicero thinks that people obtain divination from the gods. According to Cicero, there are two types of divination: artificial (auspices, haruspices, divination by lightning, stars, and other signs of nature) and natural (predictions in a dream, in a state of ecstasy, before death). In relation to divination, we see how multi- dimensional Cicero’s beliefs were: as a philosopher, he can accept or deny divination; as a Roman politician, he regards divination as an important instrument of the Roman religious rituals. Cicero opposes superstition to religion in his theological works, but in his secular works, he uses superstition and religion as synonyms. Rezumat. În articolul de față este analizată atitudinea lui Cicero față de zei, religie, divinație și superstiție. Cicero urmează tradiția recunoscând existența zeilor și considerându-i nemuritori, cu suflet și antropomorfi. El este ambivalent în ceea ce privește interacțiunea divinitate-oameni. Cicero consideră că religia este importantă pentru romani ca o consecință a unei tradiții populare — nu era propriul său punct de vedre. Divinația, în viziunea lui, se putea obține de la zei. După Cicero, există două tipuri de divinație: artificială (auspicii, haruspicii, divinație prin fulger, stele, alte semne ale naturii) și naturală (preziceri într-un vis, într-o stare de extaz, înainte de moarte). -

Taking Sides and the Prehistory of Impartiality

1. PREHISTORIES OF IMPARTIALITY TAKING SIDES AND THE PREHISTORY OF IMPARTIALITY Anita Traninger 1. Introduction: Taking Sides In his article “Taking Sides in Philosophy”, Gilbert Ryle inveighs against the ‘party-labels’ commonly awarded in philosophy. He impugns in partic- ular the conventional requirement to declare to what school one belongs because ‘[t]here is no place for “isms” in philosophy’.1 In concluding, how- ever, he is prepared to make ‘a few concessions’: Although, as I think, the motive of allegiance to a school or a leader is a non- philosophic and often an anti-philosophic motive, it may have some good results. Partisanship does generate zeal, combativeness, and team-spirit. [. .] Pedagogically, there is some utility in the superstition that philosophers are divided into Whigs and Tories. For we can work on the match-winning propensities of the young, and trick them into philosophizing by encourag- ing them to try to “dish” the Rationalists, or “scupper” the Hedonists.2 Even though Ryle chooses to reduce the value of taking sides to a propae- deutic set-up as a helpmeet for the young to come up with striking argu- ments, what he describes is precisely the modus operandi of dialectics, which had since antiquity been the methodological basis of philosophy. Dialectics conceived of thinking as a dialogue, and an agonistic one at that: it consisted in propounding a thesis and attacking it through questions. Problems were conceived of as being a choice between two positions, whence the name the procedure received in Roman times: in utramque partem disserere, arguing both sides of a question or arguing pro and con- tra. -

Readingsample

Studies on Ancient Moral and Political Philosophy 1 What is Up to Us? Studies on Agency and Responsibility in Ancient Philosophy von Edited by Pierre Destrée, Ricardo Salles 1. Academia Verlag St. Augustin bei Bonn 2014 Verlag C.H. Beck im Internet: www.beck.de ISBN 978 3 89665 634 6 Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei beck-shop.de DIE FACHBUCHHANDLUNG Pierre Destrée, Ricardo Salles and Marco Zingano 1 Introduction Pierre Destrée, Ricardo Salles and Marco Zingano The present volume brings together twenty contributions whose aim is to study the problem of moral responsibility as it arises in Antiquity in connection with the concept of what depends on us, or is up to us, through the expression eph’ hêmin and its Latin synonyms in nostra potestate and in nobis. The notion of what is up to us begins its philosophical lifetime with Aristotle. However, as the chapters by Monte Johnson and Pierre Destrée point out, it is already present in earlier authors such as Democritus and Plato, who clearly raise some of the issues that were linked to this notion in the later tradition. In Aristotle, the expression eph’ hêmin is frequently used in the plural to denote the things that are up to us in the sense that they are in our power to do or not to do. It plays a central role in his action theory insofar as the scope of deliberate choice is specifi- cally the set of these things (we deliberate about how to bring about things that it is up to us to achieve). -

Decoding the Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231

Decoding The Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231 What had motivated Gregory IX's interest in the University of Paris? The Statutes of Gregory IX 1 for the University of Paris 1231 2 define the new rights and privileges of the teachers and students and help stopping the exodus of the teachers and students from the University, particularly for Oxford. It serves to ratify with immediacy as per a perceived denial 3 of justice, which had been sanctioned by Queen Blanche in 1229 and resulted in the teachers’ 2-year suspension of their teaching for the courses in retaliation. 4 Well-versed in the political situation of Europe 5, Pope Gregory IX’s 6 worries seem well-founded an exodus of teachers and students from The University of Paris does happen before the enactment of The Statutes. The teacher-student exodus in Europe has always been a widespread phenomenon.7 Gregory XI’s bestow on students’ right and privileges may well be his being a past student of The University of Paris, but his strong stance in anti-hereticism might point to his intended control over the teachers and students 8 carries much water. While no ulterior motive could justly be implied to Gregory IX, as a nephew of the 1 Based on the translation from Dana C. Munro, trans., University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints , (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1897), Vol. II: No. 3, pp. 7-11 2 Hereafter called The Statutes. 3 The trouble originated in a quarrel in an inn in Paris which developed into a fight between the students and the citizens of Paris. -

Erasmus + Agreement

Annex to Erasmus+ Inter-Institutional Agreement Institutional Factsheet 1. Institutional Information 1.1. Institutional details Name of the institution Université Paris Diderot – Paris 7 Erasmus Code F PARIS007 EUC Nr. 28258 Institution website http://www.univ-paris-diderot.fr Online course catalogue / 1.2. Main contacts Contact person Jan DOUAT* Responsibility Central management of the Erasmus+ program Contact person for Erasmus+ partners Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 59 53 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 Email: [email protected] Contact person Floriane THOREZ* Responsibility Contact person for incoming students / Internships Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 05 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] Contact person Valérie BEAUDOIN* Responsibility Contact person for outgoing students Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 34 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] The email address will remain identical even in the case of a turnover Annex to Erasmus + Inter-Institutional Agreement | Institutional Factsheet Page 1 / 4 2. Detailed requirements and additional information 2.1. Recommended language skills Following agreement with our institution, the sending institution is responsible for providing support to its nominated candidates so that they can have the recommended language skills at the start of the study or teaching period: COURSES ARE TAUGHT IN FRENCH Type of mobility Subject area Language(s) of instruction Recommended language of instruction -

Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna

1 Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna Department of Philosophy, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3090 [email protected] Place of Birth: Athens, Greece Nationality: Greek (EU) & USA Languages: Ancient Greek, Latin, French (fluent), English (fluent), Modern Greek (fluent), Italian (competent), German (reading) AREA OF SPECIALIZATION Ancient Philosophy AREAS OF COMPETENCE Siècle des Lumières (French Enlightment), Early Modern Philosophy, topics in Epistemology, Moral Psychology, and Ethics. EDUCATION 1988 PhD (Thèse de doctorat), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1984-86 Doctoral Research, fully enrolled graduate student at the University of Cambridge, King’s College 1984 Diplôme d’Études Approfondies (DEA, equivalent to the MA), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1983 Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy summa cum laude (Πτυχεῖον summa cum laude), Philosophy, University of Athens ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2006–present University of California at Santa Barbara, Full Professor 2000–2006 University of California at Santa Barbara, Associate Professor 1997–2000 University of California at Santa Barbara, Assistant Professor 1997 (Winter) University of California at Santa Barbara, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2010 (Spring) University of Crete, Holder of the Michelis Chair in Aesthetics at the Department of Philosophy and Social Studies 1994–1996 Pomona College, Visiting Assistant Professor 1992–1993 University of Glasgow, Scotland, Research Fellow 1991–1992 California State University at San Bernardino, Lecturer -

Dr. Jeffrey Dirk Wilson CV

Photo credit: Robert M. West Jeffrey Dirk Wilson “For natures such as mine, a journey is invaluable: it enlivens, corrects, teaches, and cultivates.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson: CV—May 20, 2021 With tomatoes on my right, cucumbers on my left, and apples behind me. “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an useful plant to its culture.” Thomas Jefferson 2 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson: CV—May 20, 2021 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson 103c Aquinas Hall School of Philosophy The Catholic University of America 410.452.8465 [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ Areas of Specialization: Areas of Competence: Ancient Greek Philosophy Art and Language Classical Metaphysics Epistemology Political Philosophy Ethics Human Nature Academic Experience: Collegiate Associate Professor (formerly Clinical Associate Professor), The School of Philosophy of the Catholic University of America; courses taught: “The Classical Mind,” “The Modern Mind,” “Metaphysics,” “Philosophy of Art” “Philosophy of Knowledge,” “Philosophy of Human Nature,” “Philosophy of Natural Right and Natural Law,” “Political Philosophy,” “Philosophy of Language” “Senior Seminar: The Metaphysics of Beauty”: 2015-present. Non-Residential Fellow, Instituto de Filosofía Edith Stein: 2021-present. Clinical Assistant Professor, The School of Philosophy of The Catholic University of America: 2009-2015. Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor, St. Mary’s Seminary and University, School of Theology; course taught: “Metaphysics”: winter-spring 2013. Lecturer (full-time), Mount St. Mary’s University, Emmitsburg, Maryland; courses taught: “From Cosmos to Citizen,” “From Self to Society,” “Moral Philosophy”: 2007-2009. Lecturer, The School of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.; courses taught: “The Classical Mind,” “The Modern Mind”: 2005-2006, fall 2006.” Member of the Library Committee for the School of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.: 2005-2006. -

WUDR Biology

www.cicerobook.com Biology 2021 TOP-500 Double RankPro 2021 represents universities in groups according to the average value of their ranks in the TOP 500 of university rankings published in a 2020 World University Country Number of universities Rank by countries 1-10 California Institute of Technology Caltech USA 1-10 Harvard University USA Australia 16 1-10 Imperial College London United Kingdom Austria 2 1-10 Massachusetts Institute of Technology USA Belgium 7 1-10 Stanford University USA Brazil 1 1-10 University College London United Kingdom Canada 12 1-10 University of California, Berkeley USA China 14 1-10 University of Cambridge United Kingdom Czech Republic 1 1-10 University of Oxford United Kingdom Denmark 4 1-10 Yale University USA Estonia 1 11-20 Columbia University USA Finland 4 11-20 Cornell University USA France 9 11-20 ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich Switzerland Germany 26 11-20 Johns Hopkins University USA Greece 1 11-20 Princeton University USA Hong Kong 3 11-20 University of California, Los Angeles USA Ireland 4 11-20 University of California, San Diego USA Israel 4 11-20 University of Pennsylvania USA Italy 11 11-20 University of Toronto Canada Japan 6 11-20 University of Washington USA Netherlands 9 21-30 Duke University USA New Zealand 2 21-30 Karolinska Institutet Sweden Norway 3 21-30 Kyoto University Japan Portugal 2 21-30 Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich Germany Rep.Korea 5 21-30 National University of Singapore Singapore Saudi Arabia 2 21-30 New York University USA Singapore 2 21-30 -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

The Self-Sufficiency of the Good Man Against the Need for Friendship

THE SELF-SUFFICIENCY OF THE GOOD MAN AGAINST THE NEED FOR FRIENDSHIP. A DISCUSSION CONCERNING THE IMPORTANCE OF FRIENDSHIP FOR THE GOOD MAN IN CICERO. CORY SLOAN SUBMITTED WITH A VIEW TO OBTAIN THE DEGREE OF M.LITT. NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND, MAYNOOTH DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY, FACULTY OR ARTS, CELTIC STUDIES, AND PHILOSOPHY AUGUST 2012 HEAD OF DEPARTMENT DR. MICHAEL DUNNE SUPERVISED BY DR. AMOS EDELHEIT 1 Summary Cicero wrote in Book Three of On Duties, that the Stoic sage being absolutely good and and perfect was the only one that could be truly happy. For his happiness was based in his virtue and as he had perfect virtue, he had perfect and lasting happiness. Yet the Peripatetics saw that happiness was not a self-sufficient idea and was instead an amalgamation of external goods. Virtue for them was a factor that contributed to happiness, for the Stoics it was essential for happiness. It would appear on inital observation that the life of the Stoic sage was a solitary one, aloof from the rest of humanity. Yet the Stoics maintained that this was the best and happiest form of life, a life lived in accordance with Nature. However, the Peripatetics maintained that nature loves nothing solitary and man is not a solitary animal. In order for him to fullfill his natural end and achieve eudaimonia he would natually be drawn towards the company of others. Cicero highlights the tension between Stoic idealism and Peripatetic pragmatism in his discussion on happiness. When he essentially he askes in Book Five of the Tusculan Disputations. -

Pyrrhonism and Cartesianism – Episode: External World and Aliens

Philosophy department, CEU Budapest, Hungary Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... Pyrrhonism and 2 List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 3 IntroductionCartesianism: ................................................................................................................................ external 4 1.Methodological and practical skepticism: theory and a way of life ........................................ 6 2.Hypothetical doubt,world practical concerns and and the existence aliens of the external world .................. 13 2.1. An explanation for Pyrrhonists not questioning the existence of the external world .... 18 In partial2.2. An analysisfulfillment of whether ofPyrrhonists the requirements could expand the scope for of theirthe skepticism to include the external world .................................................................................................... 21 3.Pyrrhonism, Cartesianism and degreesome epistemologically of Masters interesting of Artsquestions ..................... 27 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ by Tamara Rendulic 37 References ............................................................................................................................... -

Stoic Ethics: Sketching Key Ideas

The Stoics | οἱ Στωικοί 7 Stoic Ethics: Sketching Key Ideas Sources. Early Stoics aim to systematise an ethics that roots in Socrates and a Cynic called Krates, who was a teacher of Zeno’s. Later Stoics (Seneca, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius) discuss philosophical therapy, which could be seen as practical ethics. Note that therapeia (θεραπεία) means ‘looking after’ or ‘taking care’. 1. Impulse (ὁρμή, hormê): the soul’s movement towards an object; desires, wants, passions; in rational beings ideally grounded in assent. 2. Oikeiôsis (οἰκείωσις): the first impulse of everything is a sort of appropriation, or familiarisation; a sort of affiliation to something that belongs to the thing in question, hence everything seeks out what is suited to it. A thing’s first act of oikeiôsis is to maintain itself in existence, or to main its constitution (pneumatic coherence). This is like Spinoza’s conatus, according to which all things strive perservere in their being (Ethics IIIP6). Oikeiôsis is continuous: minimally, keeping tenor; maximally, appropriate the cosmic constitution. We are cosmopolites (πολίτης τοῦ κόσμου, politês tou kosmou). 3. Kathêkon (καθῆκον): proper function, whatever we do that is consistent with our nature and has a justification/reason; the appropriate. If x is part of our nature, then x-ing is best/rational for us to do. Prescriptive power. See LS53Q: impulsive impressions are evaluative, that x is kathêkon (for me). 4. Indifferents (ἀδιάφορος, adiaphoros): even what conventionally seems very valuable or disvaluable, such as health or poverty, the value of most things is indifferent, even death and life. Indifferents have no intrinsic moral value: they are neither good nor bad.