Using Functional Approach in Translating Arab Spring Topics: Aljazeera and BBC Arabic As Study Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development

Published by the British Broadcorrmn~Corporarion. 35 Marylebone High Sneer, London, W.1, and printed in England by Warerlow & Sons Limited, Dunsruble and London (No. 4894). BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development PUBLISHED TO MARK THE 4oTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BBC AUGUST 1962 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION SOUND RECORDING The Introduction of Magnetic Tape Recordiq Mobile Recording Eqcupment Fine-groove Discs Recording Statistics Reclaiming Used Magnetic Tape LOCAL BROADCASTING. STEREOPHONIC BROADCASTING EXTERNAL BROADCASTING TRANSMITTING STATIONS Early Experimental Transmissions The BBC Empire Service Aerial Development Expansion of the Daventry Station New Transmitters War-time Expansion World-wide Audiences The Need for External Broadcasting after the War Shortage of Short-wave Channels Post-war Aerial Improvements The Development of Short-wave Relay Stations Jamming Wavelmrh Plans and Frwencv Allocations ~ediumrwaveRelav ~tatik- Improvements in ~;ansmittingEquipment Propagation Conditions PROGRAMME AND STUDIO DEVELOPMENTS Pre-war Development War-time Expansion Programme Distribution Post-war Concentration Bush House Sw'tching and Control Room C0ntimn.t~Working Bush House Studios Recording and Reproducing Facilities Stag Economy Sound Transcription Service THE MONITORING SERVICE INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION CO-OPERATION IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH ENGINEERING RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ELECTRICAL INTERFERENCE WAVEBANDS AND FREQUENCIES FOR SOUND BROADCASTING MAPS TRANSMITTING STATIONS AND STUDIOS: STATISTICS VHF SOUND RELAY STATIONS TRANSMITTING STATIONS : LISTS IMPORTANT DATES BBC ENGINEERING DIVISION MONOGRAPHS inside back cover THE BEGINNING OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UP TO 1939) Although nightly experimental transmissions from Chelmsford were carried out by W. T. Ditcham, of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, as early as 1919, perhaps 15 June 1920 may be looked upon as the real beginning of British broadcasting. -

Brave New World Service a Unique Opportunity for the Bbc to Bring the World to the UK

BRAVE NEW WORLD SERVIce A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR THE BBC TO BRING THE WORLD TO THE UK JOHN MCCaRTHY WITH CHARLOTTE JENNER CONTENTS Introduction 2 Value 4 Integration: A Brave New World Service? 8 Conclusion 16 Recommendations 16 INTERVIEWEES Steven Barnett, Professor of Communications, Ishbel Matheson, Director of Media, Save the Children and University of Westminster former East Africa Correspondent, BBC World Service John Baron MP, Member of Foreign Affairs Select Committee Rod McKenzie, Editor, BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat and Charlie Beckett, Director, POLIS BBC 1Xtra News Tom Burke, Director of Global Youth Work, Y Care International Richard Ottaway MP, Chair, Foreign Affairs Select Committee Alistair Burnett, Editor, BBC World Tonight Rita Payne, Chair, Commonwealth Journalists Mary Dejevsky, Columnist and leader writer, The Independent Association and former Asia Editor, BBC World and former newsroom subeditor, BBC World Service Marcia Poole, Director of Communications, International Jim Egan, Head of Strategy and Distribution, BBC Global News Labour Organisation (ILO) and former Head of the Phil Harding, Journalist and media consultant and former World Service training department Director of English Networks and News, BBC World Service Stewart Purvis, Professor of Journalism and former Lindsey Hilsum, International Editor, Channel 4 News Chief Executive, ITN Isabel Hilton, Editor of China Dialogue, journalist and broadcaster Tony Quinn, Head of Planning, JWT Mary Hockaday, Head of BBC Newsroom Nick Roseveare, Chief Executive, BOND Peter -

Implications of the BBC World Service Cuts

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Implications of the BBC World Service Cuts Written evidence Only those submissions written specifically for the Committee and accepted by the Committee as evidence for the inquiry into the Implications of the BBC World Service Cuts are included. 1 List of written evidence 1 Gilberto Ferraz Page 4 2 Corinne Podger 6 3 Rosie Kaynak 7 4 Keith Perron 8 5 Jonathan Stoneman 11 6 Keith Somerville 13 7 Sir John Tusa 19 8 John Rowlett 23 9 Jacqueline Stainburn 24 10 Richard Hamilton 25 11 Elzbieta Rembowska 26 12 Ian Mitchell 27 13 Marc Starr 28 14 Andrew Bolton 29 15 Patrick Xavier 30 16 Ailsa Auchnie 31 17 Catherine Westcott 32 18 Caroline Driscoll 35 19 BECTU 37 20 Rajesh Joshi, Rajesh Priyadarshi 40 and Marianne Landzettel 21 Clem Osei 44 22 Sam Miller 45 23 The Kenya National Kiswahili Association (CHAKITA) 47 24 Mike Fox 50 25 Kofi Annan 51 26 Geraldine Timlin 52 27 Nigel Margerison 53 28 Dennis Sewell 54 29 Voice of the Listener & Viewer 56 30 Kiyo Akasaka 60 31 Neville Harms 61 32 M Plaut 64 33 Graham Mytton 65 34 National Union of Journalists 67 35 National Union of Journalists Parliamentary Group 76 36 Trish Flanagan 78 37 Ben Hartshorn 80 38 Naleen Kumar 81 39 Jorge da Paz Rodrigues 83 40 BBC World Service 84 41 BBC World Service 89 2 42 Marc Glinert 100 43 Andrew Tyrie MP 101 44 BBC World Service 103 3 Written evidence from Gilberto Ferraz (Retired member of the World Service, in which served for 30 years) PROPOSED CLOSING DOWN OF THE BBC PORTUGUESE LANGUAGE SERVICE The announcement of the closure of the Portuguese Language Service to Africa is lamentable and wrong for the following reasons: 1. -

India and Asia-Pacific

The AIBs 2013 The short list Current affairs documentary | radio ABC International - Radio Australia/Radio National Background Briefing: PNG Land Scandal Grey Heron Media Documentary on One - Take No More Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty In the Footsteps of Sandzak Youths Who Fight in Syria Radio Taiwan International My Days at the Mental Ward Voice of Nigeria Health Corner: Managing Autism Voice of Russia FGM - The Horror of Hidden Abuse Creative feature | radio Classic FM Beethoven: The Man Revealed Kazakhstan TV & Radio Corporation Classicomania Nuala Macklin – independent producer Below the Radar Radio Taiwan International Once upon a Taiwan Voice of Nigeria Ripples Voice of Russia Out to Dry: A London Launderette on the Line Investigative documentary | radio BBC Arabic Arab Refugees in Scotland Radio Free Asia Lost but not Forgotten: Justice Sought for Missing Uyghurs Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Victims of 88 (AKA 2009) Tinderbox Production An Unspeakable Act Live journalism | radio Middle East Broadcasting Networks Afia Darfur - Darfurian Refugees BBC 5 Live Victoria Derbyshire Show: Animal Research Lab Radio New Zealand International The Auckland Tornado Voice of Russia The News Show (Death of Margaret Thatcher) International radio personality Classic FM John Suchet Voice of America Paul Westpheling Voice of America Steve Ember Voice of Russia Tim Ecott Children’s factual programme or series | TV ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation Matanglawin (Hawkeye) Sabang Dragons Australian Broadcasting Corporation My Great Big Adventure - -

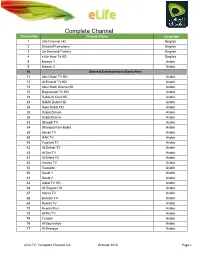

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Written Evidence Submitted by the BBC

Written evidence submitted by the BBC The DCMS Sub-committee on Online Harms and Disinformation Covid-19 Inquiry April 2020 Executive summary 1. The BBC is the leading public service broadcaster in the UK, with a mission to inform, educate and entertain. Our first public purpose is to provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them, and we deliver this across national, local and global news services.1 2. The Editorial Guidelines are the standards that underpin all our journalism, at all times, including during the Covid-19 pandemic. They apply to all our content, wherever and however it is received. Producing and upholding these Editorial Guidelines is an obligation across the BBC and all output made in accordance with these Editorial Guidelines fulfills our public purposes and meets and goes beyond the requirements of our regulator, Ofcom. 3. Coverage of Covid-19 is dominating the UK news across all platforms. And with a plethora of cross platform content, people are most likely to turn to the BBC’s TV, radio and online services for the latest news on the pandemic (82%)2, significantly more than any other source. 4. BBC News has attracted record audiences across platforms with our nations and regions, UK wide and international coverage highlighting the importance of impartial and accurate news at this time. 5. The BBC remains the UK’s primary source for news. In a world of fake news and disinformation online, audiences said they turn to the BBC for a reliable take on events and this reputation for accuracy and trust sends audiences to the BBC during breaking news and to verify facts.3 During the Covid-19 pandemic 83% of people trust coverage on BBC TV4; and audiences from the UK and around the world have come to BBC News in their millions to stay informed and seek trusted advice on how they can protect themselves and those most at risk. -

THE MIDDLE EAST and Countries of The

THE MIDDLE EAST and countries of the FSU A GUIDE TO LISTENING IN ENGLISH GMT +3 TO GMT +4½ MARCH – OCTOBER 2021 including Eastern Mediterranean, Gulf States, North and South Sudan, Iraq (GMT +3), UAE (GMT +4), Iran and South Afghanistan (GMT +4½) Where you see this sign v you will hear a short News Update at 30 minutes past the hour GMT SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 0:00 News News News News News News News 0:00 0:06 Business Matters v The Science Hour World Business Report v Business Matters v Business Matters v Business Matters v Business Matters v 0:06 0:32 Discovery (rpt) 0:32 1:00 The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v 1:00 1:32 The Conversation When Katty Met Carlos The Climate Question The Documentary (Tue) The Compass Assignment World Football 1:32 2:00 News News News News News News News 2:00 2:06 The Fifth Floor v Weekend Weekend Feature v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v 2:06 2:32 Documentary v (B) The Story 2:32 2:50 Witness Over To You Witness Witness Witness Witness 2:50 3:00 News News The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v 3:00 3:06 The Real Story (rpt) v FOOC v 3:06 3:32 The Cultural Frontline The Conversation In The Studio The Documentary (Wed) The Food Chain Heart & Soul 3:32 4:00 The Newsroom v The Newsroom v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v 4:00 4:32 Trending The Documentary (Tue) 4:32 4:50 Ros Atkins On… (rpt) 4:50 5:00 Weekend v Weekend v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday -

Pdf, (Consulted in June 2020)

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XXVI-1 | 2021 The BBC and Public Service Broadcasting in the Twentieth Century BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad? Le Service arabe de la BBC, 1938-1995 : Soft Power ou pratique reithienne à l’étranger ? Houcine Msaddek Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/7056 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.7056 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Electronic reference Houcine Msaddek, “BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad?”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XXVI-1 | 2021, Online since 05 December 2020, connection on 05 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/7056 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ rfcb.7056 This text was automatically generated on 5 January 2021. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad? 1 BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad? Le Service arabe de la BBC, 1938-1995 : Soft Power ou pratique reithienne à l’étranger ? Houcine Msaddek I dedicate this work in memory of my father who was a devoted listener of BBC Arabic in the nineteen-sixties and throughout the seventies. Introduction 1 BBC Arabic is both the largest and oldest of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s non- English language services. Launched in January 1938 in an almost direct response to Mussolini’s increasingly provocative anti-British Arabic language broadcasts aired from Bari, the Arabic Service of the BBC has constantly cultivated the loyalty of millions of listeners in the Middle East and North Africa ever since. -

Issue 23 of Ofcom's Bulletin for Complaints About BBC Online Material

Ofcom Bulletin for complaints about BBC online material Issue number: 23 Date: 8 March 2021 Introduction This Bulletin reports on complaints made to Ofcom about the BBC’s online material. It gives the outcome of Ofcom’s consideration on each complaint received and where relevant, provides Ofcom’s opinion on whether the BBC observed the relevant standards for its online material. Under the BBC’s Charter and Agreement, set by Government and Parliament, the BBC is responsible for the editorial standards of its online material. Ofcom has a responsibility to consider and give an opinion on whether the BBC has observed relevant editorial guidelines in its online material1. This came into effect with the Digital Economy Act on 27 April 2017. Online material means content on the BBC’s website and apps. This includes written text, images, video and sound content. It does not extend to social media, Bitesize, BBC material on third party websites and World Service content, among other things. Ofcom’s published arrangements and procedures for handling complaints about BBC online material can be found on the Ofcom website. These documents contain more information about the types of complaints we will consider and the process we will normally follow when handling complaints. Complaints about BBC online material must follow the ‘BBC First’ approach, where they are made to the BBC in the first instance. If a complainant is not satisfied with the BBC’s final response to a complaint about its online material, they may seek an independent opinion on it from Ofcom. Unlike our role regulating the standards of BBC broadcasting and on demand programme services (such as the BBC iPlayer), Ofcom has no enforcement powers for BBC online material. -

Maintaining the Relevance of International Journalism – BBC's

Maintaining The Relevance Of International Journalism – BBC’s Peter Horrocks POLIS Perugia Speech blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/2011/04/14/maintaining-the-relevance-of-international-journalism-bbcs-peter-horrocks- polis-perugia-speech/ 2011-4-14 This is the text of the speech given by Peter Horrocks, the BBC’s Director of Global News, as the POLIS keynote speech at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia on April 14th. It was chaired by POLIS director Charlie Beckett. [During the recent uprisings in North Africa and across the Middle East we saw] remarkable and brave coverage by the BBC’s teams. And many news organisations have had impressive records in their response to the recent crisis. But striking as the personal bravery has been, it is not that I wished to draw your attention to. I hope you noticed the prominence in much of that material of the BBC’s non-English language teams – in particular the work of the teams from BBC Arabic, as well as BBC Persian. Those two new TV services, just 4 years and 2 years old, are now not just reporting to their own language audiences, but working cheek by jowl with the BBC News English teams. So you saw Assad Sawey in Egypt appearing, injured, alongside Peter Horrocks Lyse Doucet. But not only were Arabic correspondents appearing when they had been involved in trouble, but they appeared regularly on air, giving eye witness accounts of what was happening in Egypt and providing in depth analysis in London studios, as you saw. And more recently in Libya our Arabic service teams were operating as joining newsgathering units with BBC News. -

The BBC World Service in the Middle East: Claims to Impartiality, Or a Politics of Translation?

Tuning In: Diasporic Contact Zones at the BBC World Service Working Paper Series Working Paper No. 25 The BBC World Service in the Middle East: Claims to impartiality, or a politics of translation? Michael Jaber Tuning In: Diasporas at the World Service, The Open University May 2010 Faculty of Social Sciences, The Open University, For further information: Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK Tel: +44 (0)1908 654458 Fax: +44 (0)1908 654488 Web: www.open.ac.uk 1 The BBC World Service in the Middle East: Claims to impartiality, or a politics of translation? Michael Jaber And Gerd Baumann Michael Jaber, School of European Studies, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AS, UK. [email protected] Gerd Baumann, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Amsterdam, NL 1012 DK Amsterdam. [email protected] Abstract: As the World Service’s first foray into foreign-language broadcasting (1938) and its first initiative to branch out into non-English-language television (1994-96; 2008-present), BBC-Arabic has played a central role for the Corporation. Distrust of its claims to impartiality, however, persists. To assess both claims and critiques, we examine its politics of translation under four headings: transporting data from the field to the broadcaster; translating from one language into another; transposing data and message by inflexions of tone; and transmitting the result to selected audiences at selected times. We do so from both an etic (‘outsiders’) analysis of BBC output and an emic (‘insiders’) analysis of what audiences perceive and react to by way of critical receptions and reactions. Keywords GLOBAL MEDIA, MIDDLE EAST, IMPARTIAL TRANSLATION, INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT, COMPARATIVE METHODOLOGIES. -

103506 BBCWS Review

Our aims To be the world’s best-known and most-respected voice in international broadcasting, thereby bringing benefit to Britain To be the world’s first To be a global hub for Projecting Britain’s Promoting the English choice among international high-quality information values of trustworthiness, language, learning and broadcasters for authoritative and communication openness, fair-dealing, creativity, interest in a modern, and impartial news and enterprise and community contemporary Britain information, trusted for its accuracy, editorial Providing a forum for Offering a showcase independence and expertise the exchange of ideas for British talent across cultural, linguistic across the world and national boundaries BBC World Service Annual Review 2002/2003 1 Chairman’s introduction Abeacon of independence In December 2002, BBC World Service celebrated its 70th birthday with a global concert across five continents and a 14-hour broadcast that linked some 50 locations around the globe They were part of a season of special During the Iraq war, the BBC Arabic Service began programmes of considerable range and ambition. a new daily debate programme, Nuqtat Hewar.It They showed that the BBC still has the capacity offered a forum for radio listeners and online users to fulfil a powerful role on the world stage, just to exchange opinions – a unique offer across the as it has from its birth in 1932. Arab world. This has been a momentous year for international The programme has received thousands of emails broadcasting. The war in Iraq has meant that and texts every day, allowing major global leaders, global news services have never been more local politicians and ordinary Arabs to join prominent or important.