Maintaining the Relevance of International Journalism – BBC's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving Professional Identity Through Networked Journalism at Elite News Media

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2019 Working the News: Preserving Professional Identity Through Networked Journalism at Elite News Media Jenny Hauser Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hauser, J. (2019) Working the News: Preserving Professional Identity Through Networked Journalism at Elite News Media, Doctoral Thesis, Technological University Dublin. DOI: 10.21427/12h3-z337 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Working the news: Preserving professional identity through networked journalism at elite news media Jenny Hauser Supervisors: Dr. Harry Browne, Dr. Charlie Cullen, Prof. Michael Foley School of Media, TU Dublin Abstract The concept of journalism as a profession has arguably been fraught and contested throughout its existence. Ideologically, it is founded on a claim to norms and a code of ethics, but in the past, news media also held material control over mass communication through broadcast and print which were largely inaccessible to most citizens. The Internet and social media has created a news environment where professional journalists and their work exist side-by-side with non-journalists. In this space, acts of journalism also can be and are carried out by non-journalists. -

BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development

Published by the British Broadcorrmn~Corporarion. 35 Marylebone High Sneer, London, W.1, and printed in England by Warerlow & Sons Limited, Dunsruble and London (No. 4894). BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development PUBLISHED TO MARK THE 4oTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BBC AUGUST 1962 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION SOUND RECORDING The Introduction of Magnetic Tape Recordiq Mobile Recording Eqcupment Fine-groove Discs Recording Statistics Reclaiming Used Magnetic Tape LOCAL BROADCASTING. STEREOPHONIC BROADCASTING EXTERNAL BROADCASTING TRANSMITTING STATIONS Early Experimental Transmissions The BBC Empire Service Aerial Development Expansion of the Daventry Station New Transmitters War-time Expansion World-wide Audiences The Need for External Broadcasting after the War Shortage of Short-wave Channels Post-war Aerial Improvements The Development of Short-wave Relay Stations Jamming Wavelmrh Plans and Frwencv Allocations ~ediumrwaveRelav ~tatik- Improvements in ~;ansmittingEquipment Propagation Conditions PROGRAMME AND STUDIO DEVELOPMENTS Pre-war Development War-time Expansion Programme Distribution Post-war Concentration Bush House Sw'tching and Control Room C0ntimn.t~Working Bush House Studios Recording and Reproducing Facilities Stag Economy Sound Transcription Service THE MONITORING SERVICE INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION CO-OPERATION IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH ENGINEERING RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ELECTRICAL INTERFERENCE WAVEBANDS AND FREQUENCIES FOR SOUND BROADCASTING MAPS TRANSMITTING STATIONS AND STUDIOS: STATISTICS VHF SOUND RELAY STATIONS TRANSMITTING STATIONS : LISTS IMPORTANT DATES BBC ENGINEERING DIVISION MONOGRAPHS inside back cover THE BEGINNING OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UP TO 1939) Although nightly experimental transmissions from Chelmsford were carried out by W. T. Ditcham, of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, as early as 1919, perhaps 15 June 1920 may be looked upon as the real beginning of British broadcasting. -

Layout 1 (Page 8)

April 27 2004 Ariel International he walls of my small office in a Colombo suburb are present BBC World’s flagship adorned with my press cuttings. One writer says I ought weekly cinema programme Talking T to be forcibly married off to Osama Bin Laden, another I Movies. Each week we report on that I should be the BBC’s first suicide bomber. I have been called the very latest Hollywood films – and increas- a Tamil Tiger, but the Tigers are against me too. (That’s me with ingly on global cinema. We’re an extremely the Tigers, Left) Some of the extreme attacks on my reporting are lean operation and the only full time members demented, but I know people sometimes check up on me at home on the team are myself and our and that my telephone is tapped. I have just covered my second producer/reporter Laura Metzger. election here in four years, for various tv, radio and online outlets. I joined the BBC in 1976 as a news trainee, Predictably, my reporting attracted more column inches. later working as a producer on the Today programme, on Breakfast News, Apart from my assistant Dushi Kangasabapathipillai and the the now defunct Late Show and Correspondent as well as the BBC’s main Sinhalese stringer Elmo Fernando, I have worked pretty much on cinema programmes on BBC One. I’ve reported on frothy events like the my own as correspondent in the Sri Lankan capital since I moved Oscars and examined such things as the insidious publicity machine that here in 2000 from Malaysia. -

Brave New World Service a Unique Opportunity for the Bbc to Bring the World to the UK

BRAVE NEW WORLD SERVIce A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR THE BBC TO BRING THE WORLD TO THE UK JOHN MCCaRTHY WITH CHARLOTTE JENNER CONTENTS Introduction 2 Value 4 Integration: A Brave New World Service? 8 Conclusion 16 Recommendations 16 INTERVIEWEES Steven Barnett, Professor of Communications, Ishbel Matheson, Director of Media, Save the Children and University of Westminster former East Africa Correspondent, BBC World Service John Baron MP, Member of Foreign Affairs Select Committee Rod McKenzie, Editor, BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat and Charlie Beckett, Director, POLIS BBC 1Xtra News Tom Burke, Director of Global Youth Work, Y Care International Richard Ottaway MP, Chair, Foreign Affairs Select Committee Alistair Burnett, Editor, BBC World Tonight Rita Payne, Chair, Commonwealth Journalists Mary Dejevsky, Columnist and leader writer, The Independent Association and former Asia Editor, BBC World and former newsroom subeditor, BBC World Service Marcia Poole, Director of Communications, International Jim Egan, Head of Strategy and Distribution, BBC Global News Labour Organisation (ILO) and former Head of the Phil Harding, Journalist and media consultant and former World Service training department Director of English Networks and News, BBC World Service Stewart Purvis, Professor of Journalism and former Lindsey Hilsum, International Editor, Channel 4 News Chief Executive, ITN Isabel Hilton, Editor of China Dialogue, journalist and broadcaster Tony Quinn, Head of Planning, JWT Mary Hockaday, Head of BBC Newsroom Nick Roseveare, Chief Executive, BOND Peter -

Contact Information for Non-USC Activities

6/16/17 CURRICULUM VITAE JOEL W. HAY, PhD PERSONAL INFORMATION Business/Mail Address Professor of Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy & Professor of Health Policy and Economics University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics University Park Campus, Verna & Peter Dauterive Hall (VPD 214-L) 635 Downey Way Los Angeles, CA 90089-3333 USA Business Telephone Office: (818) 338-5433 Assistant: (213) 821-7940 Fax: (213) 740-3460 (ATTN: Joel Hay) E-Mail [email protected] USC Websites : http://healthpolicy.usc.edu/ListItem.aspx?ID=4 http://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/faculty/profile/?id=374 Graduate Program Website : http://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/programs/pep/ Schaeffer Center Street Address 635 Downey Way Los Angeles, CA 90089-3333 USA (Deliveries, e.g. Fedex, UPS) Main Phone/Front Desk: (213) 821-7940 J Hay Office: (213) 821-8160 Fax: (213) 740-3460 (ATTN: Samantha) http://healthpolicy.usc.edu Contact Information for Non-USC Activities Joel W. Hay, PhD 22101 Dardenne St. Calabasas, CA 91302 818-338-5433 [email protected] Joel W. Hay, Ph.D. -- C.V. -2- 6/16/17 EDUCATION 1974 B.A. (Summa cum laude), Economics, Amherst College 1975 M.A., Economics, Yale University 1976 M.Phil., Economics, Yale University 1980 Ph.D., Economics, Yale University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE March 2009 – Present Full Professor (with tenure), Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy; School of Pharmacy Professor (by courtesy), Department of Economics; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. September 2009-Present Full Professor, Health Economics and Policy Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 1992 – 2009 Associate Professor (with tenure), Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy; School of Pharmacy. -

Women2women International Leadership Program

Women2Women International Leadership Program WATCH: W2W Highlight Video The Women2Women International Leadership Program (W2W) is a program of Empower Peace, a Boston, MA based non-profit whose mission is to provide Izzah, Pakistan - young people around the world with the tools needed to advance mutual respect, understanding and cultural awareness. “ It will certainly make you There is an increasing awareness of the critical role that women and girls play believe that women hold in advancing both peace and development. Research shows that families, up half the sky and you communities, and nations prosper when girls have the opportunity to participate are one of them.” fully in every aspect of society. W2W builds a network of promising young women from around the globe, engages them in the issues that define their lives, and provides them with the tools, relationships and opportunities required to lead. W2W America W2W America is where the leadership journey begins. W2W America is a 10-day summer program that takes place in Boston, MA and is specifically designed for young women between the ages of 15 to 19 years of age. For the past eight years, W2W has provided over 600 emerging international young women leaders from 43 countries with leadership training and social entrepreneurship skills, while strengthening their cultural competencies. In many communities from which W2W delegates are selected, youth are not naturally exposed to other cultures. This lack of diversity often breeds misconceptions about other peoples and societies, both domestically and internationally. Through the training, networking and heightened comprehension of global affairs learned during this program, delegates break down barriers of misunderstanding and replace them with bridges of mutual trust and respect among often-unlikely allies. -

Implications of the BBC World Service Cuts

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Implications of the BBC World Service Cuts Written evidence Only those submissions written specifically for the Committee and accepted by the Committee as evidence for the inquiry into the Implications of the BBC World Service Cuts are included. 1 List of written evidence 1 Gilberto Ferraz Page 4 2 Corinne Podger 6 3 Rosie Kaynak 7 4 Keith Perron 8 5 Jonathan Stoneman 11 6 Keith Somerville 13 7 Sir John Tusa 19 8 John Rowlett 23 9 Jacqueline Stainburn 24 10 Richard Hamilton 25 11 Elzbieta Rembowska 26 12 Ian Mitchell 27 13 Marc Starr 28 14 Andrew Bolton 29 15 Patrick Xavier 30 16 Ailsa Auchnie 31 17 Catherine Westcott 32 18 Caroline Driscoll 35 19 BECTU 37 20 Rajesh Joshi, Rajesh Priyadarshi 40 and Marianne Landzettel 21 Clem Osei 44 22 Sam Miller 45 23 The Kenya National Kiswahili Association (CHAKITA) 47 24 Mike Fox 50 25 Kofi Annan 51 26 Geraldine Timlin 52 27 Nigel Margerison 53 28 Dennis Sewell 54 29 Voice of the Listener & Viewer 56 30 Kiyo Akasaka 60 31 Neville Harms 61 32 M Plaut 64 33 Graham Mytton 65 34 National Union of Journalists 67 35 National Union of Journalists Parliamentary Group 76 36 Trish Flanagan 78 37 Ben Hartshorn 80 38 Naleen Kumar 81 39 Jorge da Paz Rodrigues 83 40 BBC World Service 84 41 BBC World Service 89 2 42 Marc Glinert 100 43 Andrew Tyrie MP 101 44 BBC World Service 103 3 Written evidence from Gilberto Ferraz (Retired member of the World Service, in which served for 30 years) PROPOSED CLOSING DOWN OF THE BBC PORTUGUESE LANGUAGE SERVICE The announcement of the closure of the Portuguese Language Service to Africa is lamentable and wrong for the following reasons: 1. -

The Middle East and Countries of The

THE MIDDLE EAST and countries of the FSU A GUIDE to LISTENING IN ENGLISH GMT +2 TO GMT +4⁄ NOVEMBER 2010 – marcH 2011 including Egypt, Eastern Mediterranean (GMT +2), Sudan, Gulf States, Iraq (GMT +3), Iran (GMT +3∕), UAE (GMT +4) and South Afghanistan (GMT +4∕) Where you see this sign v you will hear a short News Update at 30 minutes past the hour GMT SaturdaY SundaY MondaY TuesdaY WednesdaY ThursdaY FridaY GMT 0:00 News News World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v 0:00 0:06 Global Business v Heart & Soul (P) 0:06 0:32 The Interview One Planet (P) 0:32 0:41 Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup 0:41 0:50 Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 0:50 1:00 News World Briefing News News News News News 1:00 1:06 Friday Documentary v The Forum v Monday Documentary v Global Business v Wednesday Documentary v Assignment v 1:06 1:20 Sports Roundup v 1:20 1:32 Science in Action FOOC Health Check Digital Planet Discovery One Planet 1:32 2:00 News News World Briefing News News News News 2:00 2:06 Outlook v Assignment v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v 2:06 2:20 World Business News v 2:20 2:32 The Strand World of Music Letter From..... The Strand The Strand The Strand The Strand 2:32 2:41 Over to You 2:41 3:00 The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v 3:00 3:32 Politics UK Something Understood Digital Planet Americana HARDtalk/Bottom Line Heart & Soul Crossing Continents/FOOC 3:32 -

India and Asia-Pacific

The AIBs 2013 The short list Current affairs documentary | radio ABC International - Radio Australia/Radio National Background Briefing: PNG Land Scandal Grey Heron Media Documentary on One - Take No More Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty In the Footsteps of Sandzak Youths Who Fight in Syria Radio Taiwan International My Days at the Mental Ward Voice of Nigeria Health Corner: Managing Autism Voice of Russia FGM - The Horror of Hidden Abuse Creative feature | radio Classic FM Beethoven: The Man Revealed Kazakhstan TV & Radio Corporation Classicomania Nuala Macklin – independent producer Below the Radar Radio Taiwan International Once upon a Taiwan Voice of Nigeria Ripples Voice of Russia Out to Dry: A London Launderette on the Line Investigative documentary | radio BBC Arabic Arab Refugees in Scotland Radio Free Asia Lost but not Forgotten: Justice Sought for Missing Uyghurs Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Victims of 88 (AKA 2009) Tinderbox Production An Unspeakable Act Live journalism | radio Middle East Broadcasting Networks Afia Darfur - Darfurian Refugees BBC 5 Live Victoria Derbyshire Show: Animal Research Lab Radio New Zealand International The Auckland Tornado Voice of Russia The News Show (Death of Margaret Thatcher) International radio personality Classic FM John Suchet Voice of America Paul Westpheling Voice of America Steve Ember Voice of Russia Tim Ecott Children’s factual programme or series | TV ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation Matanglawin (Hawkeye) Sabang Dragons Australian Broadcasting Corporation My Great Big Adventure - -

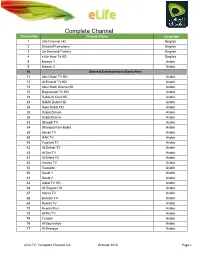

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Written Evidence Submitted by the BBC

Written evidence submitted by the BBC The DCMS Sub-committee on Online Harms and Disinformation Covid-19 Inquiry April 2020 Executive summary 1. The BBC is the leading public service broadcaster in the UK, with a mission to inform, educate and entertain. Our first public purpose is to provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them, and we deliver this across national, local and global news services.1 2. The Editorial Guidelines are the standards that underpin all our journalism, at all times, including during the Covid-19 pandemic. They apply to all our content, wherever and however it is received. Producing and upholding these Editorial Guidelines is an obligation across the BBC and all output made in accordance with these Editorial Guidelines fulfills our public purposes and meets and goes beyond the requirements of our regulator, Ofcom. 3. Coverage of Covid-19 is dominating the UK news across all platforms. And with a plethora of cross platform content, people are most likely to turn to the BBC’s TV, radio and online services for the latest news on the pandemic (82%)2, significantly more than any other source. 4. BBC News has attracted record audiences across platforms with our nations and regions, UK wide and international coverage highlighting the importance of impartial and accurate news at this time. 5. The BBC remains the UK’s primary source for news. In a world of fake news and disinformation online, audiences said they turn to the BBC for a reliable take on events and this reputation for accuracy and trust sends audiences to the BBC during breaking news and to verify facts.3 During the Covid-19 pandemic 83% of people trust coverage on BBC TV4; and audiences from the UK and around the world have come to BBC News in their millions to stay informed and seek trusted advice on how they can protect themselves and those most at risk. -

Syria & the CNN Effect: What Role Does the Media Play in Policy

Syria & the CNN Effect: What Role Does the Media Play in Policy-Making? Lyse Doucet Abstract: Syria’s devastating war unfolds during unprecedented flows of imagery on social media, test- ing in new ways the media’s influence on decision-makers. Three decades ago, the concept of a “CNN Effect” was coined to explain what was seen as the power of real-time television reporting to drive responses to humanitarian crises. This essay explores the role traditional and new media played in U.S. policy-making during Syria’s crisis, including two major poison gas attacks. President Obama stepped back from the targeted air strikes later launched by President Trump after grisly images emerged on social media. But Trump’s limited action did not shift policy. Interviews with Obama’s senior advisors underline that the me- dia do not drive strategy, but they play a significant role. During the Syrian crisis, the media formed part of what officials describe as constant pressure from many actors to respond, which they say led to policy failures. Syria’s conflict is a cautionary tale. The devastating conflict in Syria has again brought LYSE DOUCET is Chief Interna- into sharp focus the complex relationship between tional Correspondent for the bbc the media and interventions in civil wars in response and a Senior Fellow of Massey Col- to grave humanitarian crises. Syria’s destructive lege at the University of Toronto. war, often called the greatest human disaster of the She has been reporting on ma- twenty-first century, unfolds at a time of unparal- jor conflicts around the world for leled flows of imagery and information.