Evidence from Ancient Indian Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

Student Health Insurance Plan Faqs

Student Health Insurance Plan FAQs Table of Contents Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP) Overview 1 Student Health Services (SHS) 3 Considering SHIP 5 SHIP Options: Basic and Plus 7 Waiving SHIP 8 Affordable Care Act (ACA) 9 Graduate Student Information: For Trainee Stipends 10 Recipients and Research Assistants, Research Fellows, Teaching Assistants, and Teaching Fellows Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP) Overview Q: What is the Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP)? A: SHIP is Boston University’s insurance plan for students, offered through Aetna, a large national health insurer. Q: Who is eligible for SHIP? A: Most students who attend Boston University are eligible for SHIP. Q: Am I automatically enrolled in SHIP? A: Full-time, three-quarter time, and international undergraduate and graduate students are automatically enrolled in SHIP Basic coverage. Part-time students in degree- granting programs will need to enroll. Students on campuses other than the Charles River Campus may be automatically enrolled in the Plus option; consult your program administrator for details. Post-Doctoral Fellows are eligible to voluntarily enroll in the plan. Please contact the Post-Doctoral Professional Development and Post-Doctoral Affairs Office at [email protected] to obtain an enrollment application. Q: Can I waive SHIP coverage? A: Depending on your insurance, you may be able to waive SHIP coverage if you have other coverage that meets ACA requirements. See the Affordable Care Act (ACA) section of this FAQs document to learn more about ACA requirements. Page 1 2021/22 Student Health Insurance Plan FAQs The chart below indicates which student types may waive their SHIP coverageand under what circumstances this waiver is permitted. -

SHALLOW BOATS; DEEP ADVENTURES! Since 1984

Since 1984 SHALLOW BOATS; DEEP ADVENTURES! 1 SHOAL DRAFT STABILITY, SIMPLICITY, SPEED AND SAFETY. I’m here to talk about a belief in and a passion for shoal-draft boats, particularly the development of the Round Bottomed Sharpie. I started sailing in centreboard dinghies and that excitement has returned with these boats. As you’ll see these 2 boats have become known as Presto Boats. NEW HAVEN OYSTER- TONGING SHARPIE By definition a Sharpie is a flat-bottomed boat and a New Haven oyster-tonging sharpie looked like this. They were easy to build with their box shape & simple rigs but the boat is an ingenious piece of function and efficiency. The stern is round so the tongs don’t snag on transom corners; the freeboard is low so it’s easy to swing the tongs on board and the long centreboard trunk stops the oysters from shifting SEA OF ABACO 3 under sail. NEW HAVEN SHARPIE RIG The unstayed masts rotate through 360 degrees so the oystermen would sail to windward of the oyster beds and let the sails stream out over the bow while drifting over the beds tonging away. The sails are self-tending and self-vanged so handling is very easy. The boats are fast when loaded so you can get the oysters fresh to market. Oyster bars in big cities were the Starbucks of the late 1800s. You’d pop in for a ½ dozen as a pick-me-up. 4 On the right is an Outward Bound 30 to our design. With our contemporary Sharpies we’ve retained the principles of the traditional rig; it works as well today as it did in the 1800s. -

Coast Guard Cutter Seamanship Manual

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard COAST GUARD CUTTER SEAMANSHIP MANUAL COMDTINST M3120.9 November 2020 Commandant US Coast Guard Stop 7324 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr. Ave SE Washington, DC 20593-7324 Staff Symbol: (CG-751) Phone: (202) 372-2330 COMDTINST M3120.9 04 NOV 2020 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M3120.9 Subj: COAST GUARD CUTTER SEAMANSHIP MANUAL Ref: (a) Risk Management (RM), COMDTINST 3500.3 (series) (b) Rescue and Survival Systems Manual, COMDTINST M10470.10 (series) (c) Cutter Organization Manual, COMDTINST M5400.16 (series) (d) Naval Engineering Manual, COMDTINST M9000.6 (series) (e) Naval Ships' Technical Manual (NSTM), Wire and Fiber Rope and Rigging, Chapter 613 (f) Naval Ships’ Technical Manual (NSTM), Mooring and Towing, Chapter 582 (g) Cutter Anchoring Operations Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.19 (h) Cutter Training and Qualification Manual, COMDTINST M3502.4 (series) (i) Shipboard Side Launch and Recovery Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.25 (series) (j) Shipboard Launch and Recovery: WMSL 418’ Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.7 (series) (k) Naval Ships’ Technical Manual (NSTM), Boats and Small Craft, Chapter 583 (l) Naval Ship’s Technical Manual (NSTM), Cranes, Chapter 589 (m) Cutter Astern Fueling at Sea (AFAS) Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.20 (n) Helicopter Hoisting for Non-Flight Deck Vessels, Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), CGTTP 3-91.26 (o) Flight Manual USCG Series -

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments Monument Mitras are invited under the Adopt a Heritage project for selecting/opting monuments from the below list of Adarsh Monuments under the protection of Archaeological Survey of India. As provided under the Adopta Heritage guidelines, a prospective Monument Mitra needs to opt for monuments under a package. i.e Green monument has to be accompanied with a monument from the Blue or Orange Category. For further details please refer to project guidelines at https://www.adoptaheritage.in/pdf/adopt-a-Heritage-Project-Guidelines.pdf Please put forth your EoI (Expression of Interest) for selected sites, as prescribed in the format available for download on the Adopt a Heritage website: https://adoptaheritage.in/ Sl.No Name of Monument Image Historical Information Category The Veerabhadra temple is in Lepakshi in the Anantapur district of the Indian state of Andhra Virabhadra Temple, Pradesh. Built in the 16th century, the architectural Lepakshi Dist. features of the temple are in the Vijayanagara style 1 Orange Anantpur, Andhra with profusion of carvings and paintings at almost Pradesh every exposed surface of the temple. It is one of the centrally protected monumemts of national importance. 1 | Page Nagarjunakonda is a historical town, now an island located near Nagarjuna Sagar in Guntur district of Nagarjunakonda, 2 the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, near the state Orange Andhra Pradesh border with Telangana. It is 160 km west of another important historic site Amaravati Stupa. Salihundam, a historically important Buddhist Bhuddist Remains, monument and a major tourist attraction is a village 3 Salihundum, Andhra lying on top of the hill on the south bank of the Orange Pradesh Vamsadhara River. -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

U.S. Navy Ships-Of-The-Line

U.S. Navy – Ships-of-the-line A Frigate vs A Ship-of-the-Line: What’s the difference? FRIGATE: A vessel of war which is: 1) “ship” rigged, i.e. – with at least three masts (fore, main, & mizzen) & each mast carries the horizontal yards from which the principle sails are set; 2) this “ship-rigged vessel of war” is a FRIGATE because it has one covered, principle gun deck – USS Constitution is therefore a FRIGATE by class (illus. left) SHIP-OF-THE-LINE: A vessel of war which is: 1) “ship” rigged (see above); 2) this “ship-rigged vessel of war” is a SHIP-OF-THE-LINE because it has two or more covered gun decks – HMS Victory is therefore a SHIP-OF-THE-LINE by class (illus. right) HMS Victory (1765); 100+ guns; 820 officers Constitution preparing to battle Guerriere, & crew; oldest commissioned warship in the M.F. Corne, 1812 – PEM Coll. world, permanently dry docked in England Pg. 1 NMM Coll. An Act, 2 January 1813 – for the construction of the U.S. Navy’s first Ships-of-the-line USS Independence was the first ship-of-the-line launched for the USN from the Boston (Charlestown) Navy Yard on 22 June 1814: While rated for 74-guns, Independence was armed with 87 guns when she was launched. USS Washington was launched at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, 1 October 1814 USS Pennsylvania – largest sailing warship built for the USN USS Pennsylvania – rated for 136 guns on three covered gun decks + guns on her upper (spar) deck – the largest sailing warship ever built. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

The MARINER's MIRROR the JOURNAL of ~Ht ~Ocitt~ for ~Autical ~Tstarch

The MARINER'S MIRROR THE JOURNAL OF ~ht ~ocitt~ for ~autical ~tstarch. Antiquities. Bibliography. Folklore. Organisation. Architecture. Biography. History. Technology. Art. Equipment. Laws and Customs. &c., &c. Vol. III., No. 3· March, 1913. CONTENTS FOR MARCH, 1913. PAGE PAGE I. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY 4· A SHIP OF HANS BURGKMAIR. FISHING VESSELS. BY R. BY H. H. BRINDLEY • • 8I MORTON NANCE • • . 65 5. DocuMENTS, "THE MARINER's 2. NOTES ON NAVAL NOVELISTS. MIRROUR" (concluded.) CON· BY OLAF HARTELIE •• 7I TRIBUTED BY D. B. SMITH. 8S J. SOME PECULIAR SWEDISH 6. PuBLICATIONS RECEIVED . 86 COAST-DEFENCE VESSELS 7• WORDS AND PHRASES . 87 OF THE PERIOD I]62-I8o8 (concluded.) BY REAR 8. NOTES . • 89 ADMIRAL J. HAGG, ROYAL 9· ANSWERS .. 9I SwEDISH NAVY •• 77 IO. QUERIES .. 94 SOME OLD-TIME SHIP PICTURES. III. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY FISHING VESSELS. BY R. MORTON NANCE. WRITING in his Glossaire Nautique, concerning various ancient pictures of ships of unnamed types that had come under his observation, Jal describes one, not illustrated by him, in terms equivalent to these:- "The work of the engraver, Israel van Meicken (end of the 15th century) includes a ship of handsome appearance; of middling tonnage ; decked ; and bearing aft a small castle that has astern two of a species of turret. Her rounded bow has a stem that rises up with a strong curve inboard. Above the hawseholes and to starboard of the stem is placed the bowsprit, at the end 66 SOME OLD·TIME SHIP PICTURES. of which is fixed a staff terminating in an object that we have seen in no other vessel, and that we can liken only to a many rayed monstrance. -

Development of Lightweight Sharpies in NSW 1975 to 1985

Development of Lightweight Sharpies in NSW 1975 to 1985 By Rolf Lunsmann, May 2007 The ten year period from 1975 to 1985 saw rapid and dramatic technological development in the Sharpie class. Known in 1975 as the Australian Lightweight Sharpie and firmly established as one of Australia’s most prominent and popular restricted development classes, the boats changed over that period from being exclusively plywood hulls with soft rigs to largely a fleet of full composite construction hulls with high tension, fully adjustable rigs, very similar to the boats that we see sailing today. The many individual changes and developments that led to the transformation came from the strong, competitive fleets that were sailed in all the States and Territories of Australia. Many significant developments were Crescendo VII (N35) winning the Nationals for NSW for the generated in South Australia where Robin first time in 1966 in the hands of Robert Thompson, Ian Haselgrove, the most prolific boatbuilder in the Peden and Chris Buckingham. (Photo uncredited) class, worked with the local fleet on the progressive development of glass hulled timber decked boats and in Tasmania where many of new rigging control systems emerged, but it was New South Wales that first saw much of the innovation and many of the breakthroughs in hull and spar development. The article attempts to chronicle some of those developments. The predominant thinking among top Sharpie sailors in NSW in the mid 1970s was heavily influenced by the success Mark Peelgrane had achieved in winning three consecutive National Championships between 1971 and 1973. Peelgrane had sailed a plywood boat Eleanor Rigby (N35). -

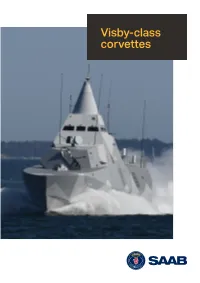

Visby-Class Corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES

Visby-class corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES Visby-class corvettes Virtually invisible in all signature bands, the innovative and powerful Visby-class corvettes from Saab continues to set the world benchmark for littoral fighting ships. Stealth, shallow draught, speed and fighting power makes Visby-class corvette a truly formidable surface combatant in the littoral arena. Visby-class corvette is a flexible surface combatant, designed for a wide range of roles: anti-surface warfare (ASuW), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), mine countermeasures (MCM), patrol and much more. Gone are the days when the mere firepower of a ship was sufficient for its own protection. The concept today is action before – or even without – being detected. All-carbon fibre The all-composite carbon-fibre sandwich hull and superstructure allows the 650-ton Visby- class corvette the same payload capacity as that of a steel ship. At the same the carbon-fibre Visby-class corvette’s all-composite carbon- means that the Visby-class corvette has at least fibre hull and superstructure is not only lighter a 50% reduction in displacement compared with than steel, but also comparable for fire resistance a steel ship. and ballistic properties, and superior to steel for Resulting combat advantages are: higher speed vulnerability to blast and underwater explosions. for the same power as conventional metal ship of In terms of life cycle costs, the carbon-fibre com- the same dimensions, as well as greater manoeu- posite is entirely superior to steel and aluminium vrability and shallower draught – both important for fatigue. And the superior corrosion resistance tactical considerations in littoral waters.