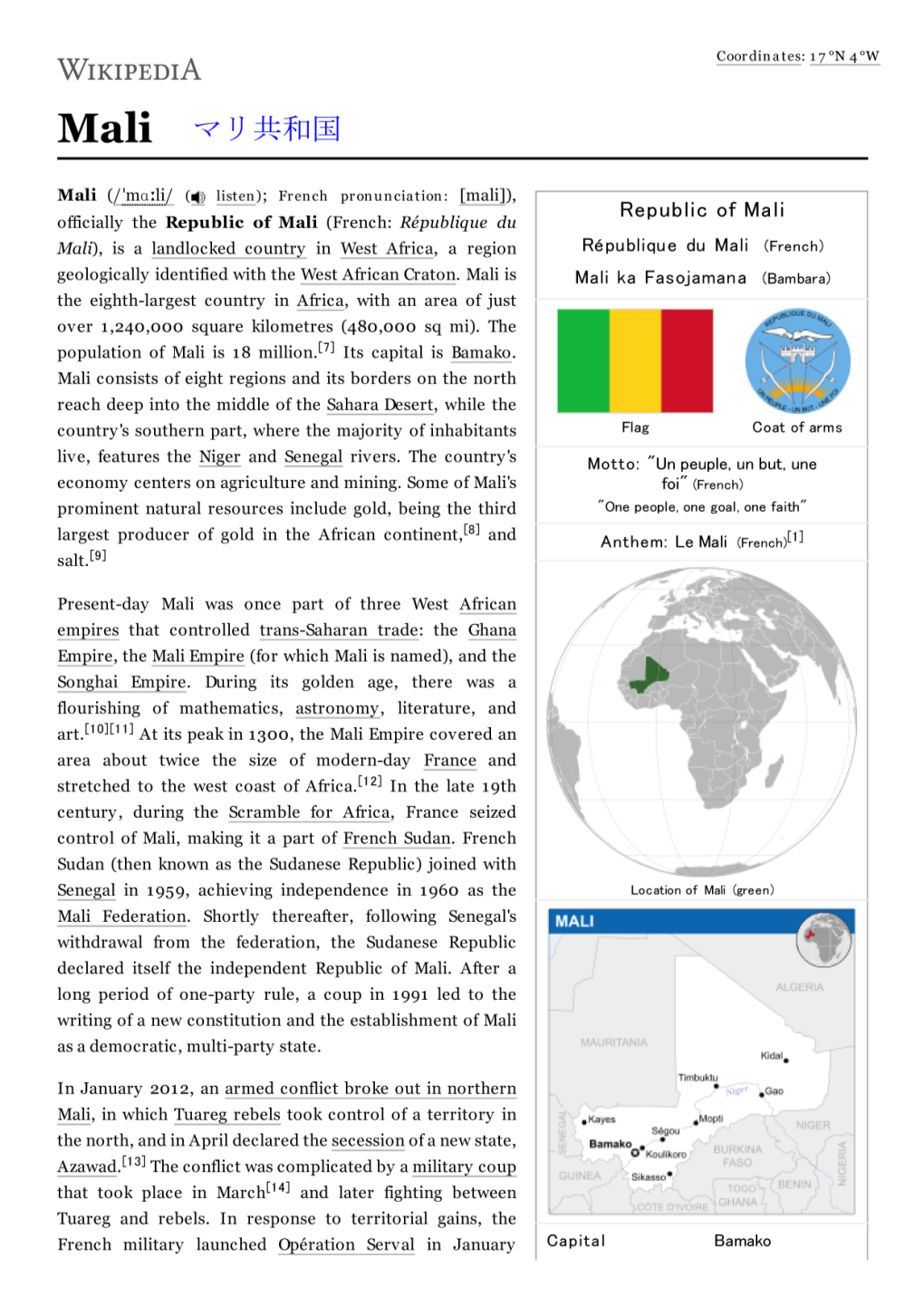

Republic of Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

When the Dust Settles

WHEN THE DUST SETTLES Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel By Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas October 2018 Copyright © 2018 Global Center on Cooperative Security All rights reserved. For permission requests, write to the publisher at: 1101 14th Street NW, Suite 900 Washington, DC 20005 USA DESIGN: Studio You London CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Heleine Fouda, Gildas Barbier, Hassane Djibo, Wafi Ougadeye, and El Hadji Malick Sow SUGGESTED CITATION: Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas, “When the Dust Settles: Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel,” Global Center on Cooperative Security, October 2018. globalcenter.org @GlobalCtr WHEN THE DUST SETTLES Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel By Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas October 2018 ABOUT THE AUTHORS JUNKO NOZAWA JUNKO NOZAWA is a Legal Analyst for the Global Center on Cooperative Security, where she supports programming in criminal justice and rule of law, focusing on human rights and judicial responses to terrorism. In the field of international law, she has contrib- uted to the work of the International Criminal Court, regional human rights courts, and nongovernmental organizations. She holds a JD and LLM from Washington University in St. Louis. MELISSA LEFAS MELISSA LEFAS is Director of Criminal Justice and Rule of Law Programs for the Global Center, where she is responsible for overseeing programming and strategic direction for that portfolio. She has spent the previous several years managing Global Center programs throughout East Africa, the Middle East, North Africa, the Sahel, and South Asia with a primary focus on human rights, capacity development, and due process in handling terrorism and related cases. -

The Lost & Found Children of Abraham in Africa and The

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International The Lost & Found Children of Abraham In Africa and the American Diaspora The Saga of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ & Their Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination by Abu Alfa Umar MUHAMMAD SHAREEF bin Farid 0 Copyright/2004- Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/www,siiasi.org All rights reserved Cover design and all maps and illustrations done by Muhammad Shareef 1 SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/ www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً The Turudbe’ Fulbe’: the Lost Children of Abraham The Persistence of Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. The Origin of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 4. Social Stratification of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 5. The Turudbe’ and the Diffusion of Islam in Western Bilad’’s-Sudan 6. Uthman Dan Fuduye’ and the Persistence of Turudbe’ Historical Consciousness 7. The Asabiya (Solidarity) of the Turudbe’ and the Philosophy of History 8. The Persistence of Turudbe’ Identity Construct in the Diaspora 9. The ‘Lost and Found’ Turudbe’ Fulbe Children of Abraham: The Ordeal of Slavery and the Promise of Redemption 10. Conclusion 11. Appendix 1 The `Ida`u an-Nusuukh of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 12. Appendix 2 The Kitaab an-Nasab of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 13. -

Das Grosse Vereinslexikon Des Weltfussballs

1 RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS ALLE ERSTLIGISTEN WELTWEIT VON 1885 BIS HEUTE AFRIKA & ASIEN BAND 1 DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS DES VEREINSLEXIKON GROSSE DAS BAND 1 AFRIKA & ASIEN RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS BAND 1 AFRIKA UND ASIEN Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Copyright © 2019 Verlag Die Werkstatt GmbH Lotzestraße 22a, D-37083 Göttingen, www.werkstatt-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Gestaltung: René Köber Satz: Die Werkstatt Medien-Produktion GmbH, Göttingen ISBN 978-3-7307-0459-2 René Köber RENÉRené KÖBERKöber Das große Vereins- DasDAS große GROSSE Vereins- LEXIKON VEREINSLEXIKONdesL WEeXlt-IFKuOßbNal lS des Welt-F ußballS DES WELTFUSSBALLSBAND 1 BAND 1 BAND 1 AFRIKAAFRIKA UND und ASIEN ASIEN AFRIKA und ASIEN Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute 15 00015 000 Vereine Vereine aus aus 6 6 000 000 Städten/Ortschaften und und 228 228 Ländern Ländern 15 000 Vereine aus 6 000 Städten/Ortschaften und 228 Ländern 1919 000 000 farbige Vereinslogos Vereinslogos 19 000 farbige Vereinslogos Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Stadien, Erfolge, Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Spielerauswahl Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, -

Book Reviews/Comptes Rendus

Book Reviews/Comptes rendus REBECCA POPENOE, Feeding Desire: Fatness, Beauty, and Sexuality Among a Saharan People. London and New York: Routledge, 2004, xv + 230 p. The glorification of thinness in Western culture, and concomitantly women‟s conflicted relationships with their bodies and food, has been well documented in sociological and anthropological literature. In Feeding Desire, Rebecca Popenoe presents the reader with a refreshingly different perspective, one in which fatness is considered the ideal for women. Yet, what is, in fact, most remarkable about this study is the evident similarities among women of decidedly dissimilar societies. Through fieldwork in a small village in Niger, Popenoe examines the practice of “fattening” among Azawagh Arab women, more commonly known as Moors. While this is a pre-marriage tradition in other cultures, the Azawagh Arabs begin fattening their female children from a very young age and the practice continues throughout their lives. Popenoe argues that fatness is valued not for the “practical” reasons often identified (such as its association with fertility or wealth), but, rather, for purely aesthetic reasons. This observation alone makes the text interesting; especially for those of us embedded in a culture that invokes both biomedical and moral arguments against corpulence. But the text also takes a multidimensional view of this practice, understanding it in the context of other factors, such as marriage and patrilineal arrangements, the centrality of Islam, blood ties and milk kinship, the intricacies of the humoral system, and an especially interesting consideration of gender and space. Moreover, Popenoe demonstrates the importance of the body, both literally and metaphorically, in an environment where few material belongings exist. -

Revue De Presse JEUX DE LA FRANCOPHONIE Avril 2020

Revue de presse JEUX DE LA FRANCOPHONIE Avril 2020 Réalisée par le Comité international des Jeux de la Francophonie (CIJF) SYNTHESE Ce document fait la synthèse de la presse parue sur internet portant sur les Jeux de la Francophonie au cours du mois d’avril 2020. • à partir du site internet des Jeux de la Francophonie ww.jeux.francophonie.org La fréquentation du site du 1er avril au 30 avril 2020 Sessions : 4 025 *Il s'agit du nombre total de sessions sur la période. Une session est la période pendant laquelle un utilisateur est actif sur son site Web, ses applications, etc. Toutes les données d'utilisation (visionnage de l'écran, événements, e-commerce, etc.) sont associées à une session. Utilisateurs: 3 251 *Utilisateurs qui ont initié au moins une session dans la plage de dates sélectionnée Pages vues : 8 865 *Il s'agit du nombre total de pages consultées. Les visites répétées d'un internaute sur une même page sont prises en compte. Au niveau de l’Internet 86 articles de presse ou brèves recensés publiées sur divers sites internet o 69 concernant les IXIes Jeux de la Francophonie o 6 concernant les précédentes éditions des Jeux de la Francophonie o 11 articles sur les lauréats des Jeux de la Francophonie o 1 vidéo 2 SOMMAIRE I. Articles sur les IXes Jeux de la Francophonie ................................................................................. 6 L’édition 2021 du 23 juillet au 1er août à Kinshasa (lematin.ma) ............................................................ 6 L’édition 2021 décalée d’une année (www.francsjeux.com) ................................................................... 7 Appel à candidatures : présélection - Jeux de la Francophonie 2021 (www.musicinafrica.net) ............. -

The Emergence of Hausa As a National Lingua Franca in Niger

Ahmed Draia University – Adrar Université Ahmed Draia Adrar-Algérie Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Letters and Language A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Master’s Degree in Linguistics and Didactics The Emergence of Hausa as a National Lingua Franca in Niger Presented by: Supervised by: Moussa Yacouba Abdoul Aziz Pr. Bachir Bouhania Academic Year: 2015-2016 Abstract The present research investigates the causes behind the emergence of Hausa as a national lingua franca in Niger. Precisely, the research seeks to answer the question as to why Hausa has become a lingua franca in Niger. To answer this question, a sociolinguistic approach of language spread or expansion has been adopted to see whether it applies to the Hausa language. It has been found that the emergence of Hausa as a lingua franca is mainly attributed to geo-historical reasons such as the rise of Hausa states in the fifteenth century, the continuous processes of migration in the seventeenth century which resulted in cultural and linguistic assimilation, territorial expansion brought about by the spread of Islam in the nineteenth century, and the establishment of long-distance trade by the Hausa diaspora. Moreover, the status of Hausa as a lingua franca has recently been maintained by socio- cultural factors represented by the growing use of the language for commercial and cultural purposes as well as its significance in education and media. These findings arguably support the sociolinguistic view regarding the impact of society on language expansion, that the widespread use of language is highly determined by social factors. -

Sociolinguistic Survey Report for the Marka-Dafin

1 SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY REPORT FOR THE MARKA-DAFIN LANGUAGE WRITTEN BY: BYRON AND ANNETTE HARRISON SIL International 2001 2 Contents 0 Introduction and Goals of the Survey 1 General Information 1.1 Language Classification 1.2 Language Location 1.2.1 Description of Location 1.2.2 Map 1.3 Population 1.4 Accessibility and Transport 1.4.1 Roads: Quality and Availability 1.4.2 Public Transport Systems 1.5 Religious Adherence 1.5.1 General Religious History 1.5.2 History of Christian Work in the Area 1.5.3 Language Use Parameters within Church Life 1.5.4 Written Materials in Marka-Dafin 1.5.5 Summary 1.6 Schools/Education 1.6.1 History of Schools in the Area 1.6.2 Types, Sites, and Size 1.6.3 Attendance and Academic Achievement 1.6.4 Existing Literacy Programs 1.6.5 Attitude toward the Vernacular 1.6.6 Summary 1.7 Facilities and Economics 1.7.1 Supply Needs 1.7.2 Medical Needs 1.7.3 Government Facilities in the Area 1.8 Traditional Culture 1.8.1 Historical Notes 1.8.2 Relevant Cultural Aspects 1.8.3 Attitude toward Culture 1.8.4 Summary 1.9 Linguistic Work in the Language Area 1.9.1 Work Accomplished in the Past 1.9.2 Present Work 2 Methodology 2.1 Sampling 2.1.1 Village Sites Chosen for the Jula Sentence Repetition Test 2.1.2 Village Sites for Sociolinguistic Survey 2.2 Lexicostatistic Survey 2.3 Dialect Intelligibility Survey 3 2.4 Questionnaires 2.5 Bilingualism Testing In Jula 3 Dialect Intercomprehension and Lexicostatistical Data 3.1 Perceived Intercomprehension 3.2 Results of the Recorded Text Tests 3.3 Lexicostatistical Analysis 3.4 -

Archives, the Digital Turn and Governance in Africa Fabienne

This article has been published in a revised form in History in Africa, 47. pp. 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1017/hia.2019.26 This version is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. No commercial re-distribution or re-use allowed. Derivative works cannot be distributed. © African Studies Association 2019 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34231 Archives, the Digital Turn and Governance in Africa Fabienne Chamelot PhD candidate University of Portsmouth School of Area Studies, History, Politics and Literature Park Building King Henry I Street Portsmouth PO1 2DZ United Kingdom +44(0)7927412143 [email protected] Dr Vincent Hiribaren Senior Lecturer in Modern African History History Department King’s College London Strand London, WC2R 2LS United Kingdom 1 [email protected] Dr Marie Rodet Senior Lecturer in the History of Africa SOAS University of London School of History, Philosophies and Religion Studies 10 Thornhaugh Street Russell Square London WC1H 0XG United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7898 4606 [email protected] 2 Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Yann Potin, along with the scholars who kindly suggested changes to our introduction at the European Conference of African Studies (2019) and those who agreed to participate in the peer-review process. 3 This manuscript has not been previously published and is not under review for publication elsewhere. 4 Fabienne Chamelot is a PhD student at the University of Portsmouth. Her research explores the making of colonial archives in the 20th century, with French West Africa and the Indochinese Union as its specific focus. -

A Peace of Timbuktu: Democratic Governance, Development And

UNIDIR/98/2 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva A Peace of Timbuktu Democratic Governance, Development and African Peacemaking by Robin-Edward Poulton and Ibrahim ag Youssouf UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.3 ISBN 92-9045-125-4 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research UNIDIR is an autonomous institution within the framework of the United Nations. It was established in 1980 by the General Assembly for the purpose of undertaking independent research on disarmament and related problems, particularly international security issues. The work of the Institute aims at: 1. Providing the international community with more diversified and complete data on problems relating to international security, the armaments race, and disarmament in all fields, particularly in the nuclear field, so as to facilitate progress, through negotiations, towards greater security for all States and towards the economic and social development of all peoples; 2. Promoting informed participation by all States in disarmament efforts; 3. Assisting ongoing negotiations in disarmament and continuing efforts to ensure greater international security at a progressively lower level of armaments, particularly nuclear armaments, by means of objective and factual studies and analyses; 4. -

(Between Warrior and Helplessness in the Valley of Azawaɤ ) Appendix 1: Northern Mali and Niger Tuareg Participation in Violenc

Appendix 1: Northern Mali and Niger Tuareg Participation in violence as perpetrators, victims, bystanders from November 2013 to August 2014 (Between Warrior and Helplessness in the Valley of Azawaɤ ) Northern Mali/Niger Tuareg participation in violence (perpetrators, victims, bystanders) November 2013 – August 2014. Summarized list of sample incidents from Northern Niger and Northern Mali from reporting tracking by US Military Advisory Team, Niger/Mali – Special Operations Command – Africa, USAFRICOM. Entries in Red indicate no Tuareg involvement; Entries in Blue indicate Tuareg involvement as victims and/or perpetrators. 28 November – Niger FAN arrests Beidari Moulid in Niamey for planning terror attacks in Niger. 28 November – MNLA organizes protest against Mali PMs Visit to Kidal; Mali army fires on protestors killing 1, injuring 5. 30 November – AQIM or related forces attack French forces in Menaka with Suicide bomber. 9 December – AQIM and French forces clash in Asler, with 19 casualties. 14 December – AQIM or related forces employ VBIED against UN and Mali forces in Kidal with 3 casualties. 14 December – MUJWA/AQIM assault a Tuareg encampment with 2 casualties in Tarandallet. 13 January – AQIM or related forces kidnap MNLA political leader in Tessalit. 16 January – AQIM kidnap/executes MNLA officer in Abeibera. 17 January – AQIM or related forces plant explosive device near Christian school and church in Gao; UN forces found/deactivated device. 20 January – AQIM or related forces attacks UN forces with IED in Kidal, 5 WIA. 22 January – AQIM clashes with French Army forces in Timbuktu with 11 Jihadist casualties. 24 January – AQIM or related forces fires two rockets at city of Kidal with no casualties. -

1 2011 Curriculum Vitae Susan J. Rasmussen

1 2011 Curriculum Vitae Susan J. Rasmussen, Anthropology Areas of Research Specialization: Religion and Symbolism; Gender; Aging and Life Course; Healing and Personhood; Verbal Art and Performance; Anthropology and Human Rights; Culture Theories, in particular in relation to aesthetics and the senses; Ethnographic Analysis, in particular in relation to memory and personal narrative; African Humanities Telephone (office) (713)743-3987 Mailing Address Susan J. Rasmussen Professor of Anthropology Department of Comparative Cultural Studies and Anthropology McElhinney Hall University of Houston Houston, Texas 77204-5020 USA e-mail [email protected] fax (713)743-3798 Academic Training Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Ph.D. in Anthropology, minor African Studies; May 1986 University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois M.A. in Social Sciences and Cross-Cultural Studies; 1973 Faculte de lettres, Universite de Dijon, Dijon, France Certificate in French language and culture; 1969 Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois B.A. in Anthropology; June, 1971 Teaching and Professional Experience University of Houston, Department of Anthropology, Houston, Texas (August, 1990-present; tenured, 1996, promoted to Full Professor 2000) Professor, Anthropology Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology, NHB Stop 112, Washington, D.C. 20560 (1989-90) Postdoctoral Research Fellow University of Florida, Center for African Studies and Department of Anthropology, Gainesville, Florida (1987-89) Outreach Coordinator and Visiting Professor IUPUI-Columbus,