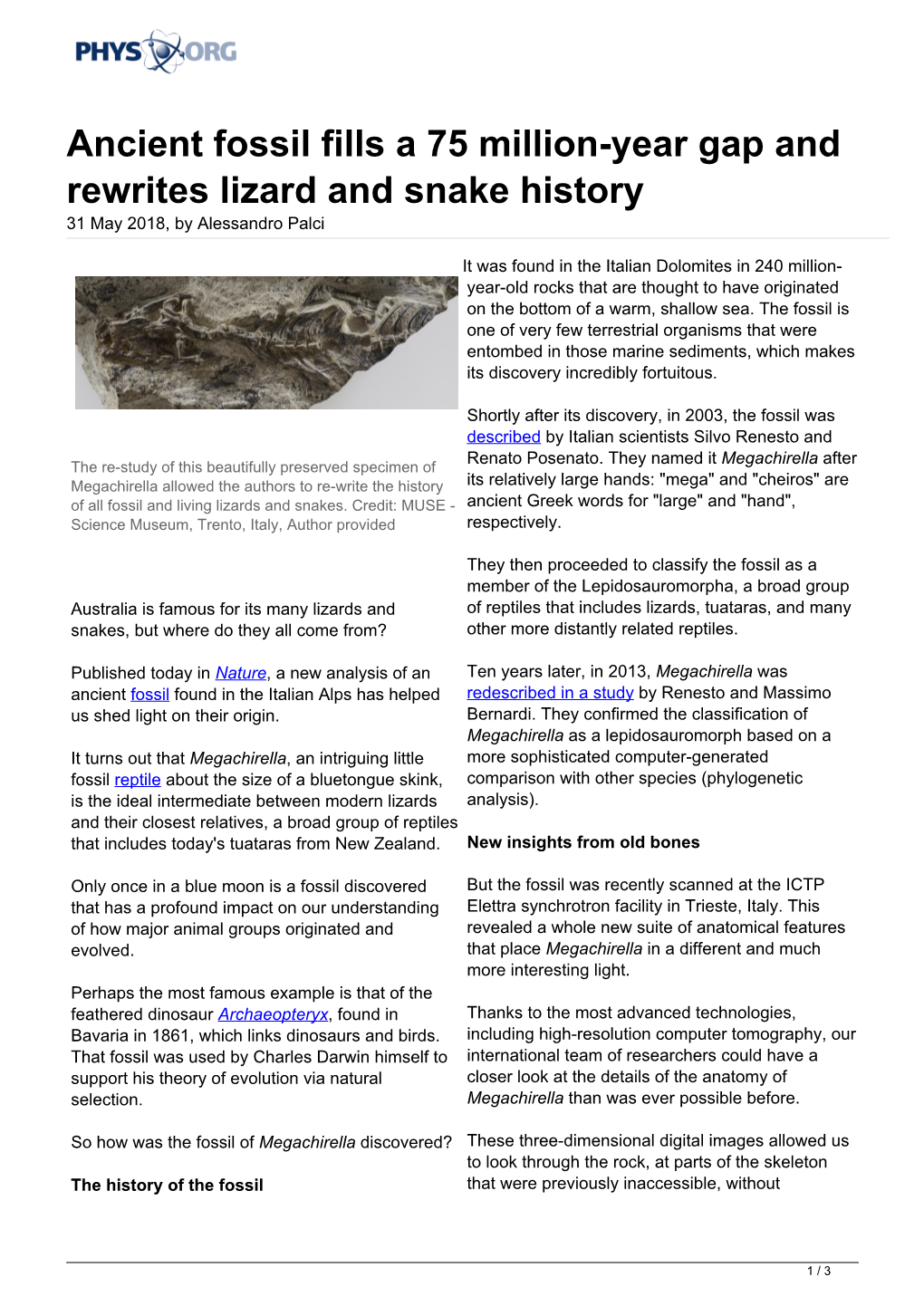

Ancient Fossil Fills a 75 Million-Year Gap and Rewrites Lizard and Snake History 31 May 2018, by Alessandro Palci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiago Rodrigues Simões

Diapsid Phylogeny and the Origin and Early Evolution of Squamates by Tiago Rodrigues Simões A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Tiago Rodrigues Simões, 2018 ABSTRACT Squamate reptiles comprise over 10,000 living species and hundreds of fossil species of lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians, with their origins dating back at least as far back as the Middle Jurassic. Despite this enormous diversity and a long evolutionary history, numerous fundamental questions remain to be answered regarding the early evolution and origin of this major clade of tetrapods. Such long-standing issues include identifying the oldest fossil squamate, when exactly did squamates originate, and why morphological and molecular analyses of squamate evolution have strong disagreements on fundamental aspects of the squamate tree of life. Additionally, despite much debate, there is no existing consensus over the composition of the Lepidosauromorpha (the clade that includes squamates and their sister taxon, the Rhynchocephalia), making the squamate origin problem part of a broader and more complex reptile phylogeny issue. In this thesis, I provide a series of taxonomic, phylogenetic, biogeographic and morpho-functional contributions to shed light on these problems. I describe a new taxon that overwhelms previous hypothesis of iguanian biogeography and evolution in Gondwana (Gueragama sulamericana). I re-describe and assess the functional morphology of some of the oldest known articulated lizards in the world (Eichstaettisaurus schroederi and Ardeosaurus digitatellus), providing clues to the ancestry of geckoes, and the early evolution of their scansorial behaviour. -

February 2020 Issue

THE FROG AND TADPOLE STUDY GROUP NSW Inc. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/FATSNSW/ Email: [email protected] PO Box 296 Rockdale NSW 2216 NEWSLETTER No. 165 FEBRUARY 2020 Frogwatch Helpline 0419 249 728 Website: www.fats.org.au ABN: 34 282 154 794 Photo by Jayden Walsh Crucifix Frog Notaden bennettii You are invited to our FATS meeting. It’s free. Everyone is welcome. Arrive from 6.30 pm for a 7pm start. Friday 7 February 2020 FATS meet at the Education Centre, Bicentennial Pk, Sydney Olympic Park Easy walk from Concord West railway station and straight down Victoria Ave. Take a torch in winter. By car: Enter from Australia Ave at the Bicentennial Park main entrance, turn off to the right and drive through the park. It’s a one way road. Or enter from Bennelong Rd / Parkway. It is a short stretch of two way road. th FATS meeting, Friday 7 February 2020 Park in P10f car park, the last car park before the Bennelong Rd. exit gate. 6.30 pm Lost Green Tree Frogs Litoria caerulea frogs and “friends” seeking forever homes: Priority to new pet frog owners. Please bring your membership card and cash $50 donation. CONTENTS PAGE Sorry, we don’t have EFTPOS. Your NSW NPWS amphibian licence must be sighted on the night. Adopted frogs can never Last meeting 2 be released. Please contact us first if you plan to adopt a frog. Corroboree poem by Giles Watson 3 We will confirm what frogs are ready to rehome. Vale John Diamond 7.00 pm Welcome and announcements Ourimbah FATS field trip, 4 7.45 pm Our main speaker is Jordan Crawford-Ash, from Australian notes from Josie Styles Museum. -

The Making of Calibration Sausage Exemplified by Recalibrating the Transcriptomic Timetree of Jawed Vertebrates

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.19.882829; this version posted January 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. The making of calibration sausage exemplified by recalibrating the transcriptomic timetree of jawed vertebrates 1 David Marjanović 2 Department of Evolutionary Morphology, Science Programme “Evolution and Geoprocesses”, 3 Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz Institute for Evolutionary and Biodiversity Research, Berlin, 4 Germany 5 ORCID: 0000-0001-9720-7726 6 Correspondence: 7 David Marjanović 8 [email protected] 9 Keywords: timetree, calibration, divergence date, Gnathostomata, Vertebrata 10 Abstract 11 Molecular divergence dating has the potential to overcome the incompleteness of the fossil record in 12 inferring when cladogenetic events (splits, divergences) happened, but needs to be calibrated by the 13 fossil record. Ideally but unrealistically, this would require practitioners to be specialists in molecular 14 evolution, in the phylogeny and the fossil record of all sampled taxa, and in the chronostratigraphy of 15 the sites the fossils were found in. Paleontologists have therefore tried to help by publishing 16 compendia of recommended calibrations, and molecular biologists unfamiliar with the fossil record 17 have made heavy use of such works (in addition to using scattered primary sources -

2Phylogenetic Systematics and the Origins of Amphibians and Reptiles

Phylogenetic Systematics and the 2 Origins of Amphibians and Reptiles he extant amphibians and reptiles are a diverse col- lection of animals with evolutionary histories dating 2.1 Principles of Phylogenetics Tback to the Early Carboniferous period. A phylo- and Taxonomy genetic perspective helps us visualize the relationships among these organisms and interpret the evolution of Phylogenies are the basis of the taxonomic structure of rep- their physiological, morphological, and behavioral char- tiles and amphibians. A taxon (plural taxa; from the Greek acteristics. To gain this perspective, it is important to un- tax, “to put in order”) is any unit of organisms given a for- derstand how phylogenies are created and used. Thus, mal name. For example, the common five-lined skink (Ples- we begin with a brief review of phylogenetic systematics tiodon fasciatus) from eastern North America is a taxon, as is and taxonomy and then use this framework to examine its entire genus (Plestiodon), the group containing all skinks the transition from fi shlike aquatic vertebrates to the ear- (Scincidae), and several more inclusive, larger taxonomic liest terrestrial tetrapods (from the Greek tetra, “four,” + groups (Squamata, Reptilia, Tetrapoda, Vertebrata, etc.) to podos, “foot”) and the origins of modern amphibian and which it belongs. A monophyletic taxon, or clade, is made reptile groups. up of a common ancestor and all of its descendant taxa. Taxonomy is the science of categorizing, or classify- Phylogenies can be depicted in a variety of styles (Figure ing, Earth’s living organisms. A phylogeny is a hypothesis 2.1). A node is the point at which a common ancestor gives of the evolutionary relationships of these categories of rise to two sister lineages, or branches. -

Fossil Lizards and Worm Lizards (Reptilia, Squamata) from the Neogene and Quaternary of Europe: an Overview

Swiss Journal of Palaeontology (2019) 138:177–211 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13358-018-0172-y (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) REGULAR RESEARCH ARTICLE Fossil lizards and worm lizards (Reptilia, Squamata) from the Neogene and Quaternary of Europe: an overview 1 1,2 Andrea Villa • Massimo Delfino Received: 16 August 2018 / Accepted: 19 October 2018 / Published online: 29 October 2018 Ó Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT) 2018 Abstract Lizards were and still are an important component of the European herpetofauna. The modern European lizard fauna started to set up in the Miocene and a rich fossil record is known from Neogene and Quaternary sites. At least 12 lizard and worm lizard families are represented in the European fossil record of the last 23 Ma. The record comprises more than 3000 occurrences from more than 800 localities, mainly of Miocene and Pleistocene age. By the beginning of the Neogene, a marked faunistic change is detectable compared to the lizard fossil record of Palaeogene Europe. This change is reflected by other squamates as well and might be related to an environmental deterioration occurring roughly at the Oligocene/ Miocene boundary. Nevertheless, the diversity was still rather high in the Neogene and started to decrease with the onset of the Quaternary glacial cycles. This led to the current impoverished lizard fauna, with the southward range shrinking of the most thermophilic taxa (e.g., agamids, amphisbaenians) and the local disappearance of other groups (e.g., varanids). Our overview of the known fossil record of European Neogene and Quaternary lizards and worm lizards highlighted a substantial number of either unpublished or poorly known occurrences often referred to wastebasket taxa. -

Phylonyms; a Companion to the Phylocode

Pan-Lepidosauria J. A. Gauthier and K. de Queiroz, new clade name Registration Number: 118 2009; Evans and Borsuk-Bialylicka, 2009; Evans and Jones, 2010; but see Müller, 2004; De!nition: !e total clade of the crown clade Jones et al., 2013). More recently, kuehneosaurs Lepidosauria. !is is a crown-based total-clade have been inferred to be stem archosaurs close de"nition. Abbreviated de"nition: total ∇ of to Trilophosaurus buettneri by Pritchard and Lepidosauria. Nesbitt (2017), although Simões et al. (2018) placed them as either stem saurians or stem Etymology: Derived from pan (Greek), here archosaurs depending on the analysis, but in referring to “pan-monophylum,” another term either case only distantly related to T. buettneri. for “total clade,” and Lepidosauria, the name !e Early Triassic Sophineta cracoviensis and the of the corresponding crown clade; hence, “the Middle Jurassic Marmoretta oxoniensis have been total clade of Lepidosauria.” more consistently regarded as stem lepidosaurs, although that inference depends upon cor- Reference Phylogeny: Gauthier et al. (1988) rect association among disarticulated remains Figure 13, where the clade in question is named (Evans, 1991; Waldman and Evans, 1994; Lepidosauromorpha and is hypothesized to Evans, 2009; Evans and Borsuk-Bialylicka, include Younginiformes, which is no longer con- 2009; Evans and Jones, 2010; Jones et al., 2013; sidered part of the clade (see Composition). Renesto and Bernardi, 2014). Depending on the analysis, Simões et al. (2018) inferred S. Composition: Pan-Lepidosauria is composed cracoviensis to be either a stem lepidosaurian of Lepidosauria (Pan-Sphenodon plus Pan- or a stem squamatan, but they consistently Squamata, see entry in this volume) and all inferred M. -

1 a New Lepidosaur Clade

A new lepidosaur clade: the Tritosauria DAVID PETERS Independent researcher, 311 Collinsville Avenue, Collinsville, Illinois 62234 U.S.A. [email protected] RH: PETERS—TRITOSAURIA 1 ABSTRACT—Several lizard-like taxa do not nest well within the Squamata or the Rhynchocephalia. Their anatomical differences separate them from established clades. In similar fashion, macrocnemids and cosesaurids share few traits with putative sisters among the prolacertiformes. Pterosaurs are not at all like traditional archosauriforms. Frustrated with this situation, workers have claimed that pterosaurs appeared without obvious antecedent in the fossil record. All these morphological ‘misfits’ have befuddled researchers seeking to shoehorn them into established clades using traditional restricted datasets. Here a large phylogenetic analysis of 413 taxa and 228 characters resolves these issues by opening up the possibilities, providing more opportunities for enigma taxa to nest more parsimoniously with similar sisters. Remarkably, all these ‘misfits’ nest together in a newly recovered and previously unrecognized clade of lepidosaurs, the Tritosauria or ‘third lizards,’ between the Rhynchocephalia and the Squamata. Tritosaurs range from small lizard-like forms to giant marine predators and volant monsters. Some tritosaurs were bipeds. Others had chameleon-like appendages. With origins in the Late Permian, the Tritosauria became extinct at the K–T boundary. Overall, the new tree topology sheds light on this clade and several other ‘dark corners’ in the family tree of the Amniota. Now pterosaurs have more than a dozen antecedents in the fossil record documenting a gradual accumulation of pterosaurian traits. INTRODUCTION The Lepidosauria was erected by Romer (1956) to include diapsids lacking archosaur characters. Later, with the advent of computer-assisted phylogenetic analyses, 2 many of Romer’s ‘lepidosaurs’ (Protorosauria/Prolacertiformes, Trilophosauria, and Rhynchosauria) were transferred to the Archosauromorpha (Benton, 1985; Gauthier, 1986). -

Multiple Evolutionary Origins and Losses of Tooth Complexity

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042796; this version posted April 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Multiple evolutionary origins and losses of tooth 2 complexity in squamates 3 4 Fabien Lafuma*a, Ian J. Corfe*a, Julien Clavelb,c, Nicolas Di-Poï*a 5 6 aDevelopmental Biology Program, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, FIN- 7 00014 Helsinki, Finland 8 bDepartment of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5DB, United 9 Kingdom 10 cLaboratoire d’Écologie des Hydrosystèmes Naturels et Anthropisés (LEHNA), Université 11 Claude Bernard Lyon 1 – UMR CNRS 5023, ENTPE, F-69622 Villeurbanne, France 12 13 *Mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042796; this version posted April 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 14 Teeth act as tools for acquiring and processing food and so hold a prominent role in 15 vertebrate evolution1,2. In mammals, dental-dietary adaptations rely on tooth shape and 16 complexity variations controlled by cusp number and pattern – the main features of the 17 tooth surface3,4. -

2018 © 48Th European Contact L Served

Overhauling the phylogenetic origins and early evolution of lizards and 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited. 2018 © II Joint Congress snakeson Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited. 2018 © 48thTiago European R. Simões Contact Lens Society Of Ophthalmologists. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . Squamata Lizards Snakes Amphisbaenians Ca. 6.300 spp Ca. 3.500 spp 197 spp Lepidosauria = Squamata + Rhynchocephalia 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited. 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited. 2018 © 48th EuropeanSphenodon Contactpunctatus Lens Society Of Ophthalmologists. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . 2018 © II Joint Congress on Evolutionary Biology 2018. All rights reserved - Any reproduction even in part is prohibited] . -

Reptile Family Tree Peters 2021 1909 Taxa, 235 Characters

Turinia Enoplus Chondrichtyes Jagorina Gemuendina Manta Chordata Loganellia Ginglymostoma Rhincodon Branchiostoma Tristychius Pikaia Tetronarce = Torpedo Palaeospondylus Craniata Aquilolamna Tamiobatis Myxine Sphyrna Metaspriggina Squalus Arandaspis Pristis Poraspis Rhinobatos Drepanaspis Cladoselache Pteromyzon adult Promissum Chlamydoselachus Pteromyzon hatchling Aetobatus Jamoytius Squatina Birkenia Heterodontus Euphanerops Iniopteryx Drepanolepis Helodus Callorhinchus Haikouichthys Scaporhynchus Belantsea Squaloraja Hemicyclaspis Chimaera Dunyu CMNH 9280 Mitsukurina Rhinochimaera Tanyrhinichthys Isurus Debeerius Thelodus GLAHM–V8304 Polyodon hatchling Cetorhinus Acipenser Yanosteus Oxynotus Bandringa PF8442 Pseudoscaphirhynchus Isistius Polyodon adult Daliatus Bandringa PF5686 Gnathostomata Megachasma Xenacanthus Dracopristis Akmonistion Ferromirum Strongylosteus Ozarcus Falcatus Reptile Family Tree Chondrosteus Hybodus fraasi Hybodus basanus Pucapampella Osteichthyes Orodus Peters 2021 1943 taxa, 235 characters Gregorius Harpagofututor Leptolepis Edestus Prohalecites Gymnothorax funebris Doliodus Gymnothorax afer Malacosteus Eurypharynx Amblyopsis Lepidogalaxias Typhlichthys Anableps Kryptoglanis Phractolaemus Homalacanthus Acanthodes Electrophorus Cromeria Triazeugacanthus Gymnotus Gorgasia Pholidophorus Calamopleurus Chauliodus Bonnerichthys Dactylopterus Chiasmodon Osteoglossum Sauropsis Synodus Ohmdenia Amia Trachinocephalus BRSLI M1332 Watsonulus Anoplogaster Pachycormus Parasemionotus Aenigmachanna Protosphyraena Channa Aspidorhynchus -

An Enigmatic Neodiapsid Reptile from the Middle Triassic of England

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology e1781143 (18 pages) © by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1781143 ARTICLE AN ENIGMATIC NEODIAPSID REPTILE FROM THE MIDDLE TRIASSIC OF ENGLAND IACOPO CAVICCHINI,† MARTA ZAHER, and MICHAEL J. BENTON * School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K., [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT—The fossil record of early diapsids is sparse, specimens are uncommon and often incomplete, and phylogenetic relationships are hard to determine. A new taxon of early diapsid, Feralisaurus corami from the Middle Triassic of Devon, south-western England, is here named and described from an incomplete but mostly articulated skeleton, comprising skull, vertebrae, pectoral girdle, ribs, and the right forelimb. CT scanning and the resultant 3D model of the skeleton reveal anatomical details otherwise buried in the sandstone matrix. This new diapsid is characterized by a plesiomorphically high maxilla without a prominent nasal process, a quadrate with a lateral conch, a low jugal with small posterior process, conical teeth with pleurodont implantation, a high coronoid process, notochordal vertebrae, a long humerus with an entepicondylar foramen, rod-like clavicles, a ‘T’-shaped interclavicle, and a ventrolateral process of the scapulocoracoid. Phylogenetic analyses, although showing generalized weak support, retrieved Feralisaurus within Neodiapsida or stem-group Lepidosauromorpha: its morphology supports the latter hypothesis. This specimen adds to our knowledge of the early diversification of Lepidosauromorpha and of English Middle Triassic terrestrial faunas. http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:15C79035-61C3-4F45-910F-FE5749AA15A0 SUPPLEMENTAL DATA—Supplemental materials are available for this article for free at www.tandfonline.com/UJVP Citation for this article: Cavicchini, I., M. -

Middle Triassic) of Piz Da Peres (Dolomites, Northern Italy

Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy) vol. 126(2): 249-259. July 2020 A PUTATIVE JUVENILE SPECIMEN OF EUSAUROSPHARGIS DALSASSOI FROM THE ANISIAN (MIDDLE TRIASSIC) OF PIZ DA PERES (DOLOMITES, NORTHERN ITALY) SILVIO RENESTO1*, EVELYN KUSTATSCHER2,3,4 & PIERO GIANOLLA5 1*Corresponding author. Dipartimento di Scienze Teoriche ed Applicate, Università degli Studi dell’Insubria, via Dunant 3, I-21100 Varese, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Museum of Nature South Tyrol, Bindergasse/via Bottai 1, 39100 Bozen/Bolzano, Italy. 3 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Paleontology & Geobiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Richard-Wagner- Str. 10, 80333 München, Germany. 4 SNSB-Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard-Wagner-Str. 10, 80333 München, Germany. 5Department of Physics and Earth Sciences, University of Ferrara, 44100 Ferrara, Italy. To cite this article: Renesto S., Kustatscher E. & Gianolla P. (2020) - A putative juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi from the Anisian (Middle Triassic) of Piz Da Peres (Dolomites, Northern Italy). Riv. It. Paleontol. Strat., 126(2): 249-259. Keywords: Reptilia; Diapsida; juvenile individual; Eusaurosphargis; Northern Dolomites; paleogeography; basinal distribution. Abstract. The partial skeleton of a small tetrapod, collected from the lower Buchenstein Formation (upper- most Illyrian, Anisian Middle Triassic) of Piz da Peres (Northern Dolomites, Italy) is described. Incomplete ossifi- cation of some bones indicate that the specimen is a juvenile. Its absolute size and proportions, along with several skeletal structures show striking similarities with a juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi from the slightly younger Prosanto Formation (Switzerland), a taxon known also from the Anisian/Ladinian Besano Formation (Italy and Switzerland).