A Brief Study of the Evolution of the Currency And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Impact of Exchange Rate Fluctuations on Economic Growth of Nigeria

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES ECONOMIC DEPARTMENT MASTER’S PROGRAMME MASTER’S THESIS AN ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF EXCHANGE RATE FLUCTUATIONS ON ECONOMIC GROWTH OF NIGERIA UMAR ALIYU SHUAIBU NICOSIA 2017 NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES ECONOMIC DEPARTMENT MASTER’S PROGRAMME MASTER’S THESIS AN ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF EXCHANGE RATE FLUCTUATIONS ON ECONOMIC GROWTH OF NIGERIA PREPARED BY UMAR ALIYU SHUAIBU 20156331 THESIS SUPERVISOR DR. BEHIYE ÇAVUŞOĞLU NICOSIA 2017 NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Economics Master’s Program Thesis Defence An Analysis of the Impact of Exchange Rate Fluctuations on Economic Growth of Nigeria Prepared by Umar Aliyu Shuaibu 20156331 We Certify the Thesis Is Satisfactory for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science in Economics Examining Committee Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Özdeşer Chairman, Department of Economics, Near East University. Dr. Behiye Çavuşoğlu Supervisor, Department of Economics, Near East University. Dr. Berna Serener Department of Economics, Near East University. Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Sağsan Acting Director iv DEDICATION This research work is above all dedicated to Almighty Allah who through his infinite mercy guides and protects me throughout my programme. The project is therefore dedicated to my sincere beloved parents, Late Alhaji Shuaibu Aliyu and Hajiya Khadija (Mama) Umar, as an abstract reward for the foundation they laid in me from my non- existing to what I am presently. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In the name of Allah, the most beneficent and the most merciful. All praises are due to Allah the Lord of the worlds. -

Metadata on the Exchange Rate Statistics

Metadata on the Exchange rate statistics Last updated 26 February 2021 Afghanistan Capital Kabul Central bank Da Afghanistan Bank Central bank's website http://www.centralbank.gov.af/ Currency Afghani ISO currency code AFN Subunits 100 puls Currency circulation Afghanistan Legacy currency Afghani Legacy currency's ISO currency AFA code Conversion rate 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new); with effect from 7 October 2002 Currency history 7 October 2002: Introduction of the new afghani (AFN); conversion rate: 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new) IMF membership Since 14 July 1955 Exchange rate arrangement 22 March 1963 - 1973: Pegged to the US dollar according to the IMF 1973 - 1981: Independently floating classification (as of end-April 1981 - 31 December 2001: Pegged to the US dollar 2019) 1 January 2002 - 29 April 2008: Managed floating with no predetermined path for the exchange rate 30 April 2008 - 5 September 2010: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 6 September 2010 - 31 March 2011: Stabilised arrangement (exchange rate within a narrow band without any political obligation) 1 April 2011 - 4 April 2017: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 5 April 2017 - 3 May 2018: Crawl-like arrangement (moving central rate with an annual minimum rate of change) Since 4 May 2018: Other managed arrangement Time series BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.M.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A01 -

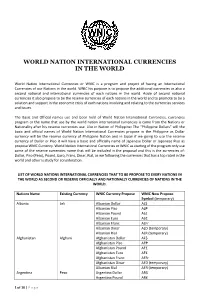

Propose Reserve Currency Table – for PDF Copy

WORLD NATION INTERNATIONAL CURRENCIES IN THE WORLD World Nation International Currencies or WNIC is a program and project of having an International Currencies of our Nations in the world. WNIC his purpose is to propose the additional currencies as also a second national and international currencies of each nations in the world. Aside of second national currencies it also propose to be the reserve currencies of each nations in the world and to promote to be a solution and support in the economic crisis of each nations involving and relating to the currencies services and issues. The Basic and Official names use and been hold of World Nation International Currencies, currencies program or the name that use by the world nation international currencies is came from the Nations or Nationality after his reserve currencies use. Like in Nation of Philippine: The “Philippine Dollars” will the basic and official names of World Nation International Currencies propose in the Philippine as Dollar currency will be the reserve currency of Philippine Nation and in Japan if we going to use the reserve currency of Dollar or Piso it will have a basic and officially name of Japanese Dollar or Japanese Piso as propose WNIC Currency. World Nation International Currencies or WNIC as starting of the program only use some of the reserve currencies name that will be included in the proposal and this is the currencies of: Dollar, Piso (Peso), Pound, Euro, Franc, Dinar, Rial, as we following the currencies that has a top rated in the world and other is study for consideration. -

The Process of Monetary Decoloniza Tjon in Africa A

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. THE PROCESS OF MONETARY DECOLONIZA TJON IN AFRICA A. MENSAH. Africa is split up into many different monetary zones which have been under- going one process of transformation or the other. The main aim of this essay is to trace the process and examine the mechanics of monetary decolonization from the time when many African countries became politicallv independent up to 1977 1. THE EVOLUTION AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MONETARY ZONES Before the colonial subjugation of Africa 1 there was, apart from barter, monetary economy in various parts of the continent2. With the physical balkanization3 of Africa during the colonial era the colonial powers found it equally expedient to effect a monetary fragmentation of the continent. Thus they introduced their own currencies or varieties of them into their areas of influence or colonies4, so that during the colonial period the following:major foreign monetary zones emerged on the African continent: the French Franc zone, the Sterling zone, the Escudo zone, the Peseta zone, the Dollar zone, the Lira zone and the Belgian Franc zones The foreign monetary zones in Africa had and still have certain common chara- cteristics. Four such features are6: i. they have a colonial origin, .ii. their ultimate decision making organs are situated outside Africa'. -

The Big Reset

REVISED s EDITION Willem s Middelkoop s TWarh on Golde and the Financial Endgame BIGs s RsE$EAUPTs The Big Reset The Big Reset War on Gold and the Financial Endgame ‘Revised and substantially enlarged edition’ Willem Middelkoop AUP Cover design: Studio Ron van Roon, Amsterdam Photo author: Corbino Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 027 3 e-isbn 978 90 4852 950 6 (pdf) e-isbn 978 90 4852 951 3 (ePub) nur 781 © Willem Middelkoop / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2016 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. To Moos and Misha In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods. -

Updated Country Chronologies

- 1 - This Draft: December 27, 2010 The Country Chronologies and Background Material to Exchange Rate Arrangements into the 21st Century: Will the Anchor Currency Hold? Ethan Ilzetzki London School of Economics Carmen M. Reinhart University of Maryland and NBER Kenneth S. Rogoff Harvard University and NBER - 2 - About the Chronologies and Charts Below we describe how to use and interpret the country chronologies. 1. Using the chronologies The individual country chronologies are also a central component of our approach to classifying regimes. The data are constructed by culling information from annual issues of various secondary sources, including Pick’s Currency Yearbook, Pick’s World Currency Report, Pick’s Black Market Yearbook, International Financial Statistics, the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Rate Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions, and the United Nations Yearbook. Constructing our data set required us to sort and interpret information for every year from every publication above. Importantly, we draw on national sources to investigate apparent data errors or inconsistencies. More generally, we rely on the broader economics literature to include pertinent information. The chronologies allow us to date dual or multiple exchange rate episodes, as well as to differentiate between pre-announced pegs, crawling pegs, and bands from their de facto counterparts. We think it is important to distinguish between say, de facto pegs or bands from announced pegs or bands, because their properties are potentially different. The chronologies also flag the dates for important turning points, such as when the exchange rate first floated, or when the anchor currency was changed. Note that we extend our chronologies as far back as possible (even though we can only classify from 1946 onwards.) The second column gives the arrangement, according to our Natural classification algorithm, which may or may not correspond to the official classification. -

SAMUEL OLATUNDE OREKOYA (Matriculation Number: 118305)

TRANSMISSION MECHANISM OF MONETARY POLICY IN NIGERIA By SAMUEL OLATUNDE OREKOYA (Matriculation Number: 118305) Bachelor of Science in Economics (O. A. U., Ile-Ife) Master of Science in Economics (U.I., Ibadan) A Thesis in the Department of Economics, submitted to the Faculty of the Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN NOVEMBER 2011 i ABSTRACT The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has pursued, among other goals, low and stable domestic price level and output growth using various monetary policy instruments. Despite these efforts, output growth rate averaged 1.32% between 1980 and 1989 and 2.87% between 1990 and 1999. Also, the monetary authority’s inflation rate target of 5.00% in 1992 and 31.00% in 1995 escalated into 44.59% and 72.81% respectively. There has been limited attempt to investigate the channels through which monetary policy affects output and prices in Nigeria. This study, therefore, empirically investigated monetary policy transmission mechanism and sought to establish the relative effectiveness of various monetary policy instruments in Nigeria. A Monetary Transmission Mechanism (MTM), predicated on Mishkin framework, that captures the impact of monetary policy in an economy was employed. The MTM focused on bank lending, exchange rate and interest rate channels that are evident in most developing economies like Nigeria. A Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) model, based on monetary policy transmission dynamics, which identified the magnitude and impact of structural shocks, was developed to test the importance of these channels. Generic, composite and separate models including the impulse responses of the channels were estimated. -

Historical Dictionary of Nigeria

HDNigeriaPODLITH.qxd 6/15/09 11:09 AM Page 1 FALOLA & GENOVA Africa History HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF AFRICA, NO. 111 Since establishing independence in 1960, Nigeria has undergone tremendous change shaped by political instability, rapid population growth, and economic turbulence. Historical Dictionary of Nigeria introduces Nigeria’s rich and complex history and includes a wealth of information on such important contemporary issues as AIDS, human of Dictionary Historical rights, petroleum, and faith-based conflict. nigeria In their thorough and comprehensive coverage of Nigeria, Toyin Falola and Ann Genova provide a chronology, an introductory essay, a bibliography, and more than 500 cross-referenced dictionary entries on notable people, places, events, and cultural practices, with an emphasis on Nigeria’s post-1990 developments. Many of the dictio- nary’s entries highlight Nigeria’s relationship to its West African neigh- bors and its membership in international organizations, such as the AU, OPEC, and the UN. Toyin Falola is the Francis Higginbotham Nalle Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of numerous works on Nigeria, including the award-winning memoir A Mouth Sweeter than Salt. NIGERIA Ann Genova is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. She is an editor and contributor to several works on Nigeria’s history and culture. For orders and information please contact the publisher SCARECROW PRESS, INC. A wholly owned subsidiary of TOYIN FALOLA The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200 ANN GENOVA Lanham, Maryland 20706 1-800-462-6420 • fax 717-794-3803 www.scarecrowpress.com HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF AFRICA Edited by Jon Woronoff 1. -

The Modern History of Exchange Rate Arrangements: a Reinterpretation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE MODERN HISTORY OF EXCHANGE RATE ARRANGEMENTS: A REINTERPRETATION Carmen M. Reinhart Kenneth S. Rogoff Working Paper 8963 http://www.nber.org/papers/w8963 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2002 The authors wish to thank Vincent Reinhart and Miguel Savastano and participants at Harvard’s Canada-US Economic and Monetary Integration Conference for useful comments and suggestions and Kenichiro Kashiwase, Daouda Sembene, and Ioannis Tokatlidis for excellent research assistance. The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the International Monetary Fund. This work was largely undertaken while the authors were professors at the University of Maryland and Harvard University, respectively. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research or the International Monetary Fund. © 2002 by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Modern History of Exchange Rate Arrangements: A Reinterpretation Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff NBER Working Paper No. 8963 June 2002 JEL No. F30, F31, F41 ABSTRACT We develop a novel system of re-classifying historical exchange rate regimes. One difference between our study and previous classification efforts is that we employ an extensive data base on market-determined parallel exchange rates. Our “natural” classification algorithm leads to a stark reassessment of the post-war history of exchange rate arrangements. -

Disbursing Officers1 Selling Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1963

DISBURSING OFFICERS1 SELLING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1963 Prescribed pursuant to section 613 of P. L. 87-195 and section 4a(3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1, Treasury Circular No. 930, for pur poses of reporting, with certain exceptions, foreign currency balances as of March 31, 1963 and transactions for the quarter ending June 30, 1963. RATE OF EXCHANGE COUNTRY F. C. TO $1.00 TYPE OF CURRENCY Aden 7.095 E. African Shilling Afghanistan 50.00 Afghani Algeria 4.888 Algerian Franc (New) Argentina 135.8 Argentine Peso Australia .4449 Australian Pound Austria 25.75 Austrian Schilling Azores 28.64 Portuguese Escudo Bahamas -3558 Bahamian Pound British Honduras 1.422 B. H. Dollar Belgium 49.88 Belgian Franc Bermuda .3567 Bermuda Pound Bolivia 11.88 Peso Brazil 460.0 Cruzeiro British W. Indies 1.708 B. W. I. Dollar Bulgerie 1.17 Leva Burma 4.718 Kyat Cambodie 34-84 Riel Canada 1.075 Canedien Dollar Ceylon 4.74 Ceylon Rupee Chile 3.240 Chilean Escudo China (Taiwan) 40.00 N. T. Dollar Colombia 9.970 Colombian Peso Congo, Republic of the 64.76 C. Franc Costa Rica 6.62 C. R. Colon Cuba 1.00 Peso Cyprus .3584 Cyprus Pound Czechoslovakia 14.34 Crown Denmark 6.896 D. Krone Dominican Republic 1.00 R. D. Peso Ecuador 21.55 Sucre El Salvador 2.500 Colon Ethiopia 2.475 E. Dollar Fiji Islands .3929 Fijian Pound Finland 3.208 Markka (New) France 4.900 Franc French West Indies 489.9 Franc (Old) DISBURSING OFFICERS' SELLING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1963 - Continued RATE OF EXCHANGE COUNTRY P. -

NBER Working Paper 23135

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE COUNTRY CHRONOLOGIES TO EXCHANGE RATE ARRANGEMENTS INTO THE 21ST CENTURY: WILL THE ANCHOR CURRENCY HOLD? Ethan Ilzetzki Carmen M. Reinhart Kenneth S. Rogoff Working Paper 23135 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23135 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2017 We wish to thank Lukas Althoff, Patricio Merlani, Paul Schmelzing, and Jordan Ward, for outstanding research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Ethan Ilzetzki, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Country Chronologies to Exchange Rate Arrangements into the 21st Century: ¸˛Will the Anchor Currency Hold? Ethan Ilzetzki, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff NBER Working Paper No. 23135 February 2017 JEL No. E5,F3,F4,N2 ABSTRACT Detailed country-by-country chronologies are an informative companion piece to our paper “Exchange Arrangements Entering the 21st Century: Which Anchor Will Hold?,” which provides a comprehensive history of anchor or reference currencies, exchange rate arrangements, and a new measure of foreign exchange restrictions for 194 countries and territories over 1946-2016. The individual country chronologies are also a central component of our approach to classifying regimes. -

History of Fiat and Paper Money Failures | Thoughts About Gold, Silver, and Other Stuff 6/28/16, 11:14 PM

History of Fiat and Paper Money Failures | Thoughts about Gold, Silver, and other stuff 6/28/16, 11:14 PM Thoughts about Gold, Silver, and other stuff Think Outside the Bank HOME ABOUT CONTACT History of Fiat and Paper Money Failures Search … LIVE GOLD AND SILVER PRICES The Fate of Paper Money “Paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value – zero.” (Voltaire, 1694-1778 ) By Mike Hewitt The first well-known widespread use of paper money was in China during the Tang (618-907 A.D.) dynasty around 800 A.D. Paper money spread to the city of Tabriz, Persia in 1294 and to parts of India and Japan between 1319 to 1331. However, its use was very short-lived in these regions. In Persia, the merchants refused to recognize the new money, thus bringing trade to a standstill. By 1455, after over 600 years, the Chinese abandoned paper money due to numerous problems of over issuance and hyperinflation. Figure 1. This Kuan note is the oldest known banknote in the world. It was made in China circa 1380. Paper money did not arrive in Europe till 1633 with the earliest known English goldsmith certificates being used not only as receipts for reclaiming deposits but also as evidence of ability to pay. In 1656, the Bank of Sweden is founded with a charter that authorizes it to accept deposits, grant loans and mortgages, and issue bills of credit. By 1660, the English Goldsmiths’ receipts became a convenient alternative to handling coins or bullion. The realisation by goldsmiths that borrowers would find them just as convenient as depositors marks the start of the use of banknotes in England.