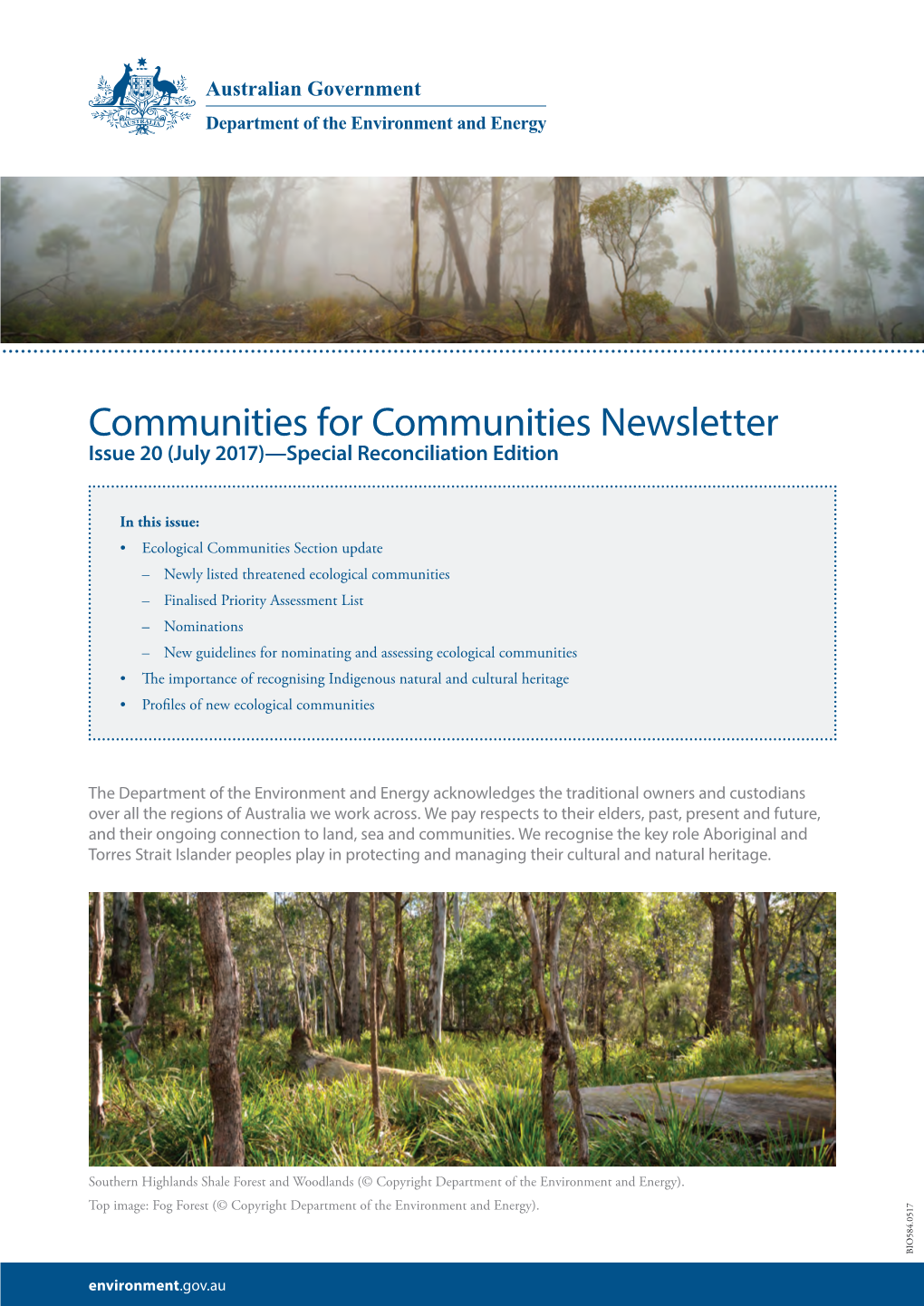

Communities for Communities Newsletter Issue 20 (July 2017)—Special Reconciliation Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborginal and Historic Gap Analysis and Future Direction Report Wilton

ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS Greater Macarthur Investigation Area Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy Final Department of Planning and Environment February 2017 Greater Macarthur Investigation Area Regional Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy i ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS Document Control Page Anita Yousif, Laressa Berehowyj and Fenella AUTHOR/HERITAGE ADVISOR Atkinson CLIENT Department of Planning and Environment Greater Macarthur Investigation Area: PROJECT NAME Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy REAL PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Various EXTENT PTY LTD INTERNAL REVIEW/SIGN OFF WRITTEN BY DATE VERSION REVIEWED APPROVED Anita Yousif, Laressa Berehowyj and Fenella 31/09/2016 1 Draft Susan McIntyre- Atkinson Tamwoy Susan McIntyre- Anita Yousif, Laressa Tamwoy, Berehowyj and Fenella 10/10/2016 Final Alan Williams Updated Aboriginal Atkinson Draft heritage maps to be substituted once data has been received. Anita Yousif, Laressa Susan McIntyre- Susan McIntyre- Berehowyj and Fenella 3/02/2017 Final Tamwoy Tamwoy Atkinson Copyright and Moral Rights Historical sources and reference materials used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced in figure captions or in text citations. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners. Unless otherwise specified in the contract terms for this project EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD: Vests copyright of all material produced by EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD (but excluding pre-existing material and material in which copyright is held by a third party) in the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title); Retains the use of all material produced by EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD for this project for EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD ongoing business and for professional presentations, academic papers or publications. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

PHYTOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS and ANTIBACTERIAL ACTIVITY of EUCALYPTUS SP LEAF EXTRACT AGAINST CLINICAL PATHOGENS S.Sasikala and J

International Standard Serial Number (ISSN): 2249-6807 International Journal of Institutional Pharmacy and Life Sciences 4(6): November-December 2014 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INSTITUTIONAL PHARMACY AND LIFE SCIENCES Life Sciences Research Article……!!! Received: 27-10-2014; Revised: 31-10-2014; Accepted: 01-11-2014 PHYTOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS AND ANTIBACTERIAL ACTIVITY OF EUCALYPTUS SP LEAF EXTRACT AGAINST CLINICAL PATHOGENS S.Sasikala and J. Kalaimathi* Department of Biochemistry, Sri Akilandeswari womens College Wandiwash, TN, India Keywords: ABSTRACT Eucalyptus globulus, Medicinal plants are considerably useful and economically Medicinal palnt, essential. They contain active constituents that are used in the Antimicrobial activity treatment of many human diseases. Infectious diseases are world’s most important reason of untimely death, killing For Correspondence: 50,000 people each day. Resistance to antimicrobial agents is J. Kalaimathi rising in a wide diversity of pathogens and numerous drug Department of Biochemistry, resistances are becoming common in diverse organisms. The Sri Akilandeswari womens plant extracts have been developed and proposed for use as College Wandiwash, TN, India antimicrobial substances. Many of the plant materials used in E-mail: traditional medicine are readily available in rural areas at relatively cheaper than modern medicine. The present study [email protected] was aimed to evaluate the antibacterial potential of methanol extract of Eucalyptus globulus against bacterial pathogens and phytochemical analysis was done. 47 Full Text Available On www.ijipls.com International Standard Serial Number (ISSN): 2249-6807 INTRODUCTION In the production of drugs, the role of plants is very important. There is a lot of drugs are produced from the plants and its various parts (Fabricant and Farnsworth 2001, Farnsworth et al., 19858) . -

Eucalyptus 2018 17-21 September 2018, Le Corum, Montpellier - France

Eucalyptus 2018 17-21 September 2018, Le Corum, Montpellier - France Eucalyptus 2018 Managing Eucalyptus plantations under global changes Abstracts Book Foreword Eucalyptus trees cover about 20 million hectares in more than 90 countries around the world with major centers in Brazil (5.7 m ha), India (3.9 m ha) and China (4.5 m ha). Eucalypts are widely grown in commercial plantations to produce raw material for the industry (pulp and paper, charcoal, sawn timber, wood panels) but also in small woodlots for the production of firewood and charcoal for domestic uses. The considerable expansion of these plantations in recent decades reflects major competitive advantages of eucalypts relative to other tree species in terms of productivity, tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, wood quality for a wide variety of uses and ability to be managed in coppice. However, the requirements in water and nutrients of eucalypt trees are high to reach high biomass productions and the environmental impact of the silviculture is still a matter of debate. In a context of global changes with more frequent drought events, temperature rise and rapid expansion of pests and diseases, the sustainability of eucalypt plantations is of concern in many regions. Interdisciplinary research is urgently needed to improve the adaptation of eucalypt plantations to global changes. Cirad and I-Site MUSE organize an international conference under the auspices of IUFRO (Division 2.08.03 Improvement and culture of eucalypts and Division 1.02.01 Ecology and silviculture of plantation forests in the tropics) to present recent advances likely to improve the management of eucalypt plantations in tropical, sub-tropical and Mediterranean regions. -

Durable Eucalypt Forests – a Multi-Regional Opportunity For

Specialty woods Durable eucalypt forests – a multi-regional opportunity for investment in New Zealand drylands Paul Millen, Shaf van Ballekom, Clemens Altaner, Luis Apiolaza, Euan Mason, Ruth McConnochie, Justin Morgenroth and Tara Murray Abstract Introduction We believe our vision for the establishment The New Zealand Dryland Forests Initiative of a durable eucalypt plantation estate is a unique (NZDFI) was established in 2008 as a collaborative tree opportunity to add value to New Zealand’s current breeding and forestry research project. The NZDFI’s forest industry. With our elite breeding populations and aim is to select and improve drought-tolerant eucalypts branding strategy we have ‘first mover’ advantage to that produce high-quality naturally ground-durable make this a reality by forest growers planting relatively hardwood. The NZDFI vision is for New Zealand to be a low-value, marginal pastoral dryland to produce high- world leader in breeding ground-durable eucalypts, and value timber. Our aim is that New Zealand will compete to be home to a valuable sustainable hardwood industry on innovation and excellence, rather than price, with based on 100,000 ha of eucalypt forests by 2050. our strategy underpinned by the increasing scarcity of tropical hardwoods and environmental constraints Markets for naturally ground-durable wood exist limiting their ongoing supply. in New Zealand’s agricultural, transport and energy E. quadrangulata, Wairarapa, age four years NZ Journal of Forestry, May 2018, Vol. 63, No. 1 11 Specialty woods A well-established NZDFI trial in Marlborough sectors. There is also potential for high-value specialty and employment could be generated through local wood products for export to international markets processing to produce high-value export products that (Millen, 2009). -

Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River

November 2017 ACT Heritage Council BACKGROUND INFORMATION Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River Block 700 MAJURA Part Blocks 662, 663, 699, 680, 701, 702, 703, 704 MAJURA Part Blocks 2002, 2091, 2117 JERRABOMBERRA OAKS ESTATE Block 22, Section 2; Block 13, Section 3; Block 4, Section 13; Block 6, Section 13, Block 5, Section 14; Part Block 15, Section 2; Part Block 19, Section 2; Part Block 20, Section 2; Part Block 21, Section 2; Part Block 5, Section 13; Part Block 1, Section 14; Part Block 4, Section 14; Part Block 1, Section 17 At its meeting of 16 November 2017 the ACT Heritage Council decided that the Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River was eligible for registration. The information contained in this report was considered by the ACT Heritage Council in assessing the nomination for the Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River against the heritage significance criteria outlined in s 10 of the Heritage Act 2004. HISTORY The Ngunnawal people are traditionally affiliated with the lands within the Canberra region. In this citation, ‘Aboriginal community’ refers to the Ngunnawal people and other Aboriginal groups within the ACT who draw significance from the place. Whilst the term ‘Aboriginal community’ acknowledges these groups in the ACT, it is recognised that their traditional territories extend outside contemporary borders. These places attest to a rich history of Aboriginal connection to the area. Traditional Aboriginal society in Canberra during the nineteenth century suffered from dramatic depopulation and alienation from traditional land based resources, although some important social institutions like intertribal gatherings and corroborees were retained to a degree at least until the 1860s. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Luise A. Hercus, 1963-1965

Finding aid HERCUS_L08 Sound recordings collected by Luise A. Hercus, 1963-1965 Prepared January 2014 by SL Last updated 30 November 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained permission from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. This collection may only be copied with the permission of Luise Hercus or her representatives. Permission must be sought from Luise Hercus or her representatives as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 16 sound tape reels (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, 3 3/4, 7 1/2 ips, mono. ; 5 in. + field tape report sheets Production history These recordings were collected between 1963 and 1965 by linguist Luise Hercus during field trips to Point Pearce, South Australia, Framlingham, Lake Condah, Drouin, Jindivick, Fitzroy, Strathmerton, Echuca, Antwerp and Swan Hill in Victoria, and Dareton, Curlwaa, Wilcannia, Hay, Balranald, Deniliquin and Quaama in New South Wales. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages and songs of the Madhi Madhi, Parnkalla, Kurnai, Gunditjmara, Yorta Yorta, Paakantyi, Ngarigo, Wemba Wemba and Wergaia peoples. -

Ntscorp Limited Annual Report 2010/2011 Abn 71 098 971 209

NTSCORP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 ABN 71 098 971 209 Contents 1 Letter of Presentation 2 Chairperson’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 NTSCORP’s Purpose, Vision & Values 8 The Company & Our Company Members 10 Executive Profiles 12 Management & Operational Structure 14 Staff 16 Board Committees 18 Management Committees 23 Corporate Governance 26 People & Facilities Management 29 Our Community, Our Service 30 Overview of NTSCORP Operations 32 Overview of the Native Title Environment in NSW 37 NTSCORP Performing the Functions of a Native Title Representative Body 40 Overview of Native Title Matters in NSW & the ACT in 2010-2011 42 Report of Performance by Matter 47 NTSCORP Directors’ Report NTSCORP LIMITED Letter OF presentation THE HON. JennY MacKlin MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, RE: 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the Commonwealth Government 2010–2013 General Terms and Conditions Relating to Native Title Program Funding Agreements I have pleasure in presenting the annual report for NTSCORP Limited which incorporates the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. Yours sincerely, MicHael Bell Chairperson NTSCORP NTSCORP ANNUAL REPORT 10/11 – 1 CHAIrperson'S Report NTSCORP LIMITED CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Company looks forward to the completion of these and other ON beHalF OF THE directors agreements in the near future. NTSCORP is justly proud of its involvement in these projects, and in our ongoing work to secure and members OF NTSCORP, I the acknowledgment of Native Title for our People in NSW. Would liKE to acKnoWledGE I am pleased to acknowledge the strong working relationship with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). -

Exhibition Catalogue Message from Our Co-Chairs

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE MESSAGE FROM OUR CO-CHAIRS In 2019 we are celebrating 10 years of the Schools Reconciliation Challenge (SRC)! For 10 years Reconciliation NSW has been engaging young people and schools in reconciliation. Our theme this year, Speaking and Listening from the Heart has inspired primary and high school students from across NSW and the ACT to create reconciliation-inspired art and writing for the SRC. We continue to be inspired by the contribution these young people, from many different backgrounds, make to reconciliation with their talent and insight. We thank each and every school, teacher, principal, parent and student who has taken part, guided and supported students and each other. It is thanks to their dedication that the SRC continues to grow each year. We are grateful for their hard work and commitment in ensuring that schools are key contributors to reconciliation processes. In 2019 we received 415 art and writing entries from students across NSW and the ACT, each reflecting the theme and their perspectives on Australia’s ongoing reconciliation journey. It is a privilege to see the depth of engagement, insight and commitment to reconciliation in action that students demonstrate ACKNOWLEDGMENT through their art and writing entries. OF COUNTRY The quality of the art and writing entries we received made the selection process for the exhibition Reconciliation NSW hard work. Many of the artworks were developed acknowledges the collaboratively, involving classes or groups of students traditional owners of under the guidance of local Aboriginal artists, parents Country throughout and community members. We thank the panel of NSW and the ACT judges: Jody Broun, Fiona Petersen, Kirli Saunders, and recognises their Jane Waters, Annie Tennant, Yvette Poshoglian and continuing connections Fiona Britton for their time and expertise in selecting to land, waters and this year’s entries. -

Aboriginal Totems

EXPLORING WAYS OF KNOWING, PROTECTING & ACKNOWLEDGING ABORIGINAL TOTEMS ACROSS THE EUROBODALLA SHIRE FAR SOUTH COAST, NSW Prepared by Susan Dale Donaldson Environmental & Cultural Services Prepared for The Eurobodalla Shire Council Aboriginal Advisory Committee FINAL REPORT 2012 THIS PROJECT WAS JOINTLY FUNDED BY COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF INDIGNEOUS CULTURAL & INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS Eurobodalla Shire Council, Individual Indigenous Knowledge Holders and Susan Donaldson. The Eurobodalla Shire Council acknowledges the cultural and intellectual property rights of the Indigenous knowledge holders whose stories are featured in this report. Use and reference of this material is allowed for the purposes of strategic planning, research or study provided that full and proper attribution is given to the individual Indigenous knowledge holder/s being referenced. Materials cited from the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Islander Studies [AIATSIS] ‘South Coast Voices’ collections have been used for research purposes. These materials are not to be published without further consent, which can be gained through the AIATSIS. DISCLAIMER Information contained in this report was understood by the authors to be correct at the time of writing. The authors apologise for any omissions or errors. ACKNOWLEDMENTS The Eurobodalla koori totems project was made possible with funding from the NSW Heritage Office. The Eurobodalla Aboriginal Advisory Committee has guided this project with the assistance of Eurobodalla Shire Council staff - Vikki Parsley, Steve Picton, Steve Halicki, Lane Tucker, Shannon Burt and Eurobodalla Shire Councillors Chris Kowal and Graham Scobie. A special thankyou to Mike Crowley for his wonderful images of the Black Duck [including front cover], to Preston Cope and his team for providing advice on land tenure issues and to Paula Pollock for her work describing the black duck from a scientific perspective and advising on relevant legislation. -

East Gippsland, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Mueller Park Address 150 Roberts Road Subiaco Lot Number 9337 Photograph (2014)

City of Subiaco - Heritage Place Record Name Mueller Park Address 150 Roberts Road Subiaco Lot Number 9337 Photograph (2014) Construction 1900 Date Architectural N/A Style Historical Reserve 9337, gazetted in 1904, comprises three distinct areas: Mueller Notes Park, a well-established urban park laid out in 1906-07 and the 1920s, with mature tree plantings, and recent playgrounds; Kitchener Park, a grassed area used for car parking with a small number of mature trees; Subiaco Oval, more recently named Patersons Stadium, a football oval with associated facilities and spectator stands, and Subiaco Oval Gates (Register of Heritage Places, RHP 5478). In the Documentary Evidence the name that pertained at each period is used. An early plan of Subiaco shows Subiaco and Mueller Roads (the latter named in honour of Ferdinand Jakob Heinrich von Mueller (1825-1896), inaugural director of Melbourne Botanic Gardens (1857-73), and Australia’s pre-eminent botanist) with the part of Reserve 591A that later became Mueller Park. During the 1890s gold boom, lack of May 2021 Page 1 City of Subiaco - Heritage Place Record accommodation in the metropolitan area for people heading to the goldfields saw many camping out, raising sanitary concerns. In 1896, men at ‘Subiaco Commonage’ (as the area of Perth Commonage, Reserve 591A, west of Thomas Street, was commonly known) protested against a notice to quit the area and unsuccessfully asked for it to be declared a camping ground. Perth City Council cleared a large number of tents from the area on numerous occasions. In July 1897, the Subiaco Council asked Perth Council to continue Townshend and Hamilton Roads through the Commonage to Subiaco Road, and both these roads and Coghlan Road were made by the early 1900s.