Creole Mustard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

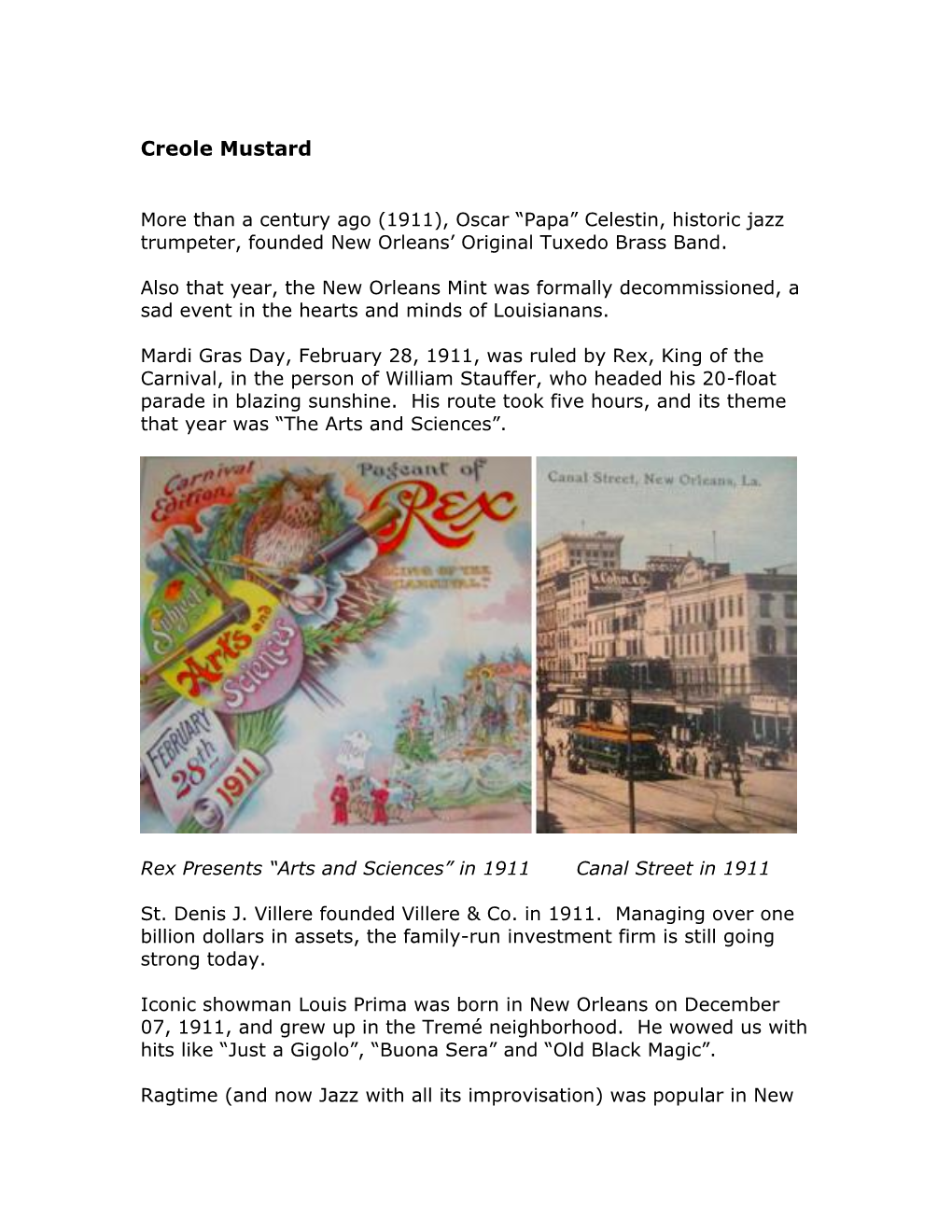

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Did You Grow Your Greens?

Did you Grow your Greens? A Share-Net Resource Book Reading-to-learn curriculum materials to support Language, Natural Sciences, Social Sciences, Life Orientation and Arts & Culture learning areas Acknowledgments The Handprint resource books have been compiled by Rob O’Donoghue and Helen Fox of the Rhodes University Environmental Education and Sustainability Unit. Lawrence Sisitka was responsible for coordination and review, and Kim Ward for editorial review and production for curriculum and Eco-School use. Development funding was provided by CAPE. Cover illustrations are by Tammy Griffin. Knowledge and activity support materials have been adapted from various sources including the Internet, and web addresses have been provided for readers to access any copyright materials directly. Available from Share-Net P O Box 394, Howick, 3290, South Africa Tel (033) 3303931 [email protected] January 2009 ISBN 978-1-919991-05-4 Any part of this resource book may be reproduced copyright free, provided that if the materials are produced in booklet or published form, there is acknowledgment of Share-Net. 1 RESOURCE BOOKS The Handprint Resource Books have been designed for creative educators who are looking for practical ideas to work with in the learning areas of the National Curriculum. The focus is on sustainability practices that can be taken up within the perspective that each learning area brings to environment and sustainability concerns. The resource books are intended to provide teachers with authentic start-up materials for change-orientated learning. The aim is to work towards re-imagining more sustainable livelihood practices in a warming world. Each start-up story was developed as a reading- to-learn account of environmental learning and change. -

Old Bay, Fresh Herbs Pickled Mustard Seeds, Homemade “Kraut”, Ketchup

V-Vegetarian/GF-Gluten Friendly/VG-Vegan East Coast Fries V. 7 Local Greens VG . 12 old bay, fresh herbs shaved vegetables, balsamic, italian bread crumbs (salmon +12, chicken +9) Hot Dog . 12 pickled mustard seeds, homemade “kraut”, ketchup Gazpacho VG, GF . 13 spiced tomato sorbet, basil, strawberry Fried Chicken Sandwich . 18 house potato roll, kewpie mayo, shredded lettuce Watermelon V, GF . 12 whipped feta, pistachio, toasted aromatics, mint The MacArthur Burger . 19 two grass fed beef patties, american cheese, shredded lettuce Greek Salad V, GF . 13 pickle, house spread heirloom tomato, cucumber, feta, gem lettuce (single 16, house made veggie burger 19, kids 9) GF . 34 Patatas Bravas GF, V . 14 Steak Frites whipped garlic aioli, smoked paprika tomato jam wagyu flat iron, herbed butter, french fries Flatbread . 16 Salmon . 29 smoked salmon, whipped creme fraiche, frisee muhammara, fava bean falafel, herb salad Flatbread V . 15 Lobster Roll . 24 burrata, pesto, cherry tomato warm lobster, herb butter, little gem lettuce, poppy seed bun GF . 19 Poke Bowl Housemade Semolina Bucatini VG . 24 yellowtail, avocado, seaweed salad, sesame dressing vegetable bolognese, almond “ricotta” puffed rice (grass fed beef +5) 8oz Creekstone New York Strip Steak 38 whipped potatoes, seasonal vegetable, house steak sauce Please advise us of any food allergies. Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. WINE BY THE GLASS SPARKLING SIGNATURE The White Knight, Prosecco, Veneto, Italy, NV 10 COCKTAILS Louis Pommery, Brut, California, NV . 12 Macarthur Mule . 15 J Vineyards, “Cuvée,” Brut, Russian River, NV 16 Elyx Vodka, Green Chartreuse, Mint, Ginger, Gloria Ferrer, Blanc De Noirs, Carneros, NV . -

Post 60 Recipes

Post 60 Recipes Cooking Measurement Equivalents 16 tablespoons = 1 cup 12 tablespoons = 3/4 cup 10 tablespoons + 2 teaspoons = 2/3 cup 8 tablespoons = 1/2 cup 6 tablespoons = 3/8 cup 5 tablespoons + 1 teaspoon = 1/3 cup 4 tablespoons = 1/4 cup 2 tablespoons = 1/8 cup 2 tablespoons + 2 teaspoons = 1/6 cup 1 tablespoon = 1/16 cup 2 cups = 1 pint 2 pints = 1 quart 3 teaspoons = 1 tablespoon 48 teaspoons = 1 cup Deviled Eggs Chef: Phil Jorgensen 6 dozen eggs 1 small onion 1 celery hot sauce horse radish mustard pickle relish mayonnaise Worcestershire sauce Boil the 6 dozen eggs in salty water While the eggs are boiling dice/slice/ grate, the celery and onion into itty bitty pieces put them in the bowl. Eggs get cooled best with lots of ice and more salt Peel and half the eggs. Drop the yokes in the bowl with onion / celery add mustard, mayo, relish Begin whupping then add some pepper 1/4 hand and 1 teaspoon of salt. Add some Worcestershire sauce 2-4 shakes Add some hot sauce 2-3 shakes. Add about 1/4 to 1/2 cup of horse radish. Keep whupping till thoroughly mixed then stuff eggs as usual. Ham Salad Chef: Brenda Kearns mayonnaise sweet pickle relish ground black pepper salt smoked boneless ham 1 small onion 2 celery stalks Dice 2 to 4 lbs smoked boneless ham. Dice 2 stalks of celery and 1 small onion. Mix ham, celery and onion with 1 to 2 cups mayonnaise. Add 1/2 teaspoon of freshly ground black pepper and 1 1/2 teaspoons salt add more to taste. -

Comparative Mapping Between Arabidopsis Thaliana and Brassica Nigra Indicates That Brassica Genomes Have Evolved Through Extensi

Copyright 1998 by the Genetics Society of America Comparative Mapping Between Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica nigra Indicates That Brassica Genomes Have Evolved Through Extensive Genome Replication Accompanied by Chromosome Fusions and Frequent Rearrangements Ulf Lagercrantz Department of Plant Biology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, S-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden Manuscript received March 27, 1998 Accepted for publication July 24, 1998 ABSTRACT Chromosome organization and evolution in the Brassicaceae family was studied using comparative linkage mapping. A total of 160 mapped Arabidopsis thaliana DNA fragments identi®ed 284 homologous loci covering 751 cM in Brassica nigra. The data support that modern diploid Brassica species are descended from a hexaploid ancestor, and that the A. thaliana genome is similar in structure and complexity to those of each of the hypothetical diploid progenitors of the proposed hexaploid. Thus, the Brassica lineage probably went through a triplication after the divergence of the lineages leading to A. thaliana and B. nigra. These duplications were also accompanied by an exceptionally high rate of chromosomal rearrangements. The average length of conserved segments between A. thaliana and B. nigra was estimated at 8 cM. This estimate corresponds to z90 rearrangements since the divergence of the two species. The estimated rate of chromosomal rearrangements is higher than any previously reported data based on comparative mapping. Despite the large number of rearrangements, ®ne-scale comparative mapping between model plant A. thal- iana and Brassica crops is likely to result in the identi®cation of a large number of genes that affect important traits in Brassica crops. NE important aspect of genome evolution is polyploid (Masterson 1994). -

Mustard, Dijon Smooth Product Information SKU 25100 Brand Esprit De Paris Pack Size 6/8.8Lb Country of Origin Canada

PRODUCT SPECIFICATIONS FORM January 2018 Mustard, Dijon Smooth Product Information SKU 25100 Brand Esprit de Paris Pack Size 6/8.8lb Country of Origin Canada Packaging Specifications Net weight per unit 8.8 lbs Net weight per case 51 lbs Gross weight per case 60 lbs Case Dimensions (LxWxH) 18.5 x 12.5 x 9.75 TiHi 7 x 4 Case Cube 1.43 Product UPC 0 46274 25100 7 Case GTIN 600 46274 25100 9 Primary: tin Packaging Material Secondary: carton box Physical Properties Tolerances for Defects* 0% non-organic foreign material Preservation Method retort *tolerance must meet all federal standards Sensory Properties - Organoleptic Appearance smooth Dijon mustard Color deep yellow to light brown, characteristic Aroma characteristic to Dijon mustard - heat, sharp Flavor characteristic to Dijon mustard - heat, sharp Microbiological Properties Value Method Product commercially sterile, exempt from microbiological testing Chemical Properties Value pH <4 Salt 5.5 - 6.5 % Acidity 2.2 - 2.8% Sulphites <10 ppm Moisture 66.5 - 69.5% Ingredient Statement water, mustard seeds, vinegar, salt, citric acid Ingredient distribution proprietary Total: 100.00% * values subject to variance Nutrition Facts Per 100g (unrounded) Calories (Kcal) 167.93 Calories from Fat (Kcal) 98.55 Total Fat (g) 10.95 Saturated Fat (g) 0 Trans Fat (g) 0 Cholesterol (mg) 0.13 Sodium (mg) 2218.94 Total Carbohydrates (g) 8.68 Dietetic Fiber (g) 5.37 Total Sugar (g) 0.48 Added Sugar (g) 0 Protein (g) 6.94 Vitamin D (mcg) 0 Calcium (mg) 54.03 Iron (mg) 0.35 Potassium (mg) 64.87 *disclaimer: values -

CID Hot Sauce.Pdf

METRIC A-A-20097F November 10, 2010 SUPERSEDING A-A-20097E December 28, 2005 COMMERCIAL ITEM DESCRIPTION HOT SAUCE The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has authorized the use of this Commercial Item Description (CID). 1. SCOPE. This CID covers hot sauce packed in commercially acceptable containers, suitable for use by Federal, State, local governments, and other interested parties; and as a component of operational rations. 2. PURCHASER NOTES. 2.1 Purchasers shall specify the following: - Type(s) of hot sauce required (Sec. 3). - When analytical requirements are different than specified (Sec. 6.1). - When analytical requirements need to be verified (Sec. 6.2). - Manufacturer’s/distributor’s certification (Sec. 9.3) or USDA certification (Sec. 9.4). 2.2 Purchasers may specify the following: - Food Defense System Survey (Sec. 9.1 with 9.2.1) or (Sec. 9.1 with 9.2.2). - Manufacturer’s quality assurance (Sec. 9.2 with 9.2.1) or (Sec. 9.2 with 9.2.2). - Packaging requirements other than commercial (Sec. 10). 3. CLASSIFICATION. The hot sauce shall conform to the following list which shall be specified in the solicitation, contract, or purchase order. Types. Type I - Hot Type II - Extra hot 4x Type III - Green Type IV - Chipotle Type V - Habanero AMSC N/A FSC 8950 A-A-20097F Type VI - Garlic Type VII - Chili and lime Type VIII - Sweet and spicy Type IX - Other 4. MANUFACTURER’S/DISTRIBUTOR’S NOTES. Manufacturer’s/distributor’s products shall meet the requirements of the: - Salient characteristics (Sec. 5). - Analytical requirements: as specified by the purchaser (Sec. -

Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties of Endogenous Phenolic Compounds from Commercial Mustard Products

Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of endogenous phenolic compounds from commercial mustard products By Ronak Fahmi A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Human Nutritional Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Canada Copyright © 2016 by Ronak Fahmi Abstract This study investigated the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of endogenous phenolic compounds in Oriental (Brassica junceae) and yellow (Sinapis alba) mustard seeds. Phenolics in selected Canadian mustard products (seeds/ powder/ flour) were extracted using Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) and their corresponding sinapate profiles were established through HPLC-DAD analysis. The antioxidant capacity of each extract was assessed by DPPH assay and correlated with the total phenolic content (TPC) measured using the Folin–Ciocalteau method. Sinapine was the major phenolic compound in all the samples analysed, with negligible amounts of sinapic acid. The sinapine content, expressed as sinapic acid equivalents (SAE), ranged from 5.36 × 103 ± 0.66 to 14.44 ± 0.43 × 103 µg SAE/g dry weight of the samples, with the highest in the yellow mustard seed extract and lowest in Oriental mustard powder. The level decreased in the following order: yellow mustard seed > Oriental mustard seed > yellow mustard bran > Oriental mustard bran > yellow mustard powder > Oriental mustard powder. Extracts from yellow mustard seeds had the highest TPC (17.61× 103 ± 1.01 µg SAE/g), while Oriental mustard powder showed the lowest TPC with 4.14 × 103 ± 0.92 µg SAE/g. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of mustard methanolic extracts ranged between 36% and 69%, with the following order for both varieties: ground mustard seed > mustard bran > mustard powder. -

Homeopathic Liquid Liquid Energetix Corp Disclaimer: This Homeopathic Product Has Not Been Evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration for Safety Or Efficacy

PARA-CHORD- homeopathic liquid liquid Energetix Corp Disclaimer: This homeopathic product has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration for safety or efficacy. FDA is not aware of scientific evidence to support homeopathy as effective. ---------- Para-Chord Active ingredients 59.1 mL contains 5.88% of: Abrotanum 12X; Artemisia 12X; Boldo 4X; Calcarea carb 15X; Chenopodium anth 12X; Cina 5X; Filix mas 4X; Granatum 12X; Graphites 12X, 30X, 60X; Nat phos 12X; Silicea 12X; Sinapis alb 12X; Spigelia anth 6C; Tanacetum 12X; Teucrium mar 5X Claims based on traditional homeopathic practice, not accepted medical evidence. Not FDA evaluated. Uses Temporary relief of abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, anal itch. Warnings In case of overdose, get medical help or contact a Poison Control Center right away. If pregnant or breast-feeding, ask a healthcare professional before use. Keep out of reach of children. Directions Take 30 drops orally twice daily or as directed by a healthcare professional. Consult a physician for use in children under 12 years of age or if symptoms worsen or persist. Other information Store at room temperature out of direct sunlight. Do not use if neck wrap is broken or missing. Shake well before use. Inactive ingredients Ethyl Alcohol, Glycerin, Purified Water. Distributed by Energetix Corp. Dahlonega, GA 30533 Questions? Comments? 800.990.7085 www.goenergetix.com energetix Para-Chord Homeopathic Remedy Abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, anal itch. 2 fl oz (59.1 mL) / 15% Ethyl Alcohol Purpose Temporary relief of abdominal -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

STAR SWEETENERS the Best of the Naturals

STAR SWEETENERS The Best of the Naturals Become sugar savvy! The term "natural" as applied to sweeteners, can mean many things. The sweeteners recommended below will provide you with steady energy because they take a long time to digest. Natural choices offer rich flavors, vitamins and minerals, without the ups and downs of refined sugars. Sugar substitutes were actually the natural sweeteners of days past, especially honey and maple syrup. Stay away from man-made artificial sweeteners including aspartame and any of the "sugar alcohols" (names ending in ol). In health food stores, be alert for sugars disguised as "evaporated cane juice" or "can juice crystals." These can still cause problems, regardless what the health food store manager tells you. My patients have seen huge improvements by changing their sugar choices. Brown rice syrup. Your bloodstream absorbs this balanced syrup, high in maltose and complex carbohydrates, slowly and steadily. Brown rice syrup is a natural for baked goods and hot drinks. It adds subtle sweetness and a rich, butterscotch-like flavor. To get sweetness from starchy brown rice, the magic ingredients are enzymes, but the actual process varies depending on the syrup manufacturer. "Malted" syrups use whole, sprouted barley to create a balanced sweetener. Choose these syrups to make tastier muffins and cakes. Cheaper, sweeter rice syrups use isolated enzymes and are a bit harder on blood sugar levels. For a healthy treat, drizzle gently heated rice syrup over popcorn to make natural caramel corn. Store in a cool, dry place. Devansoy is the brand name for powdered brown rice sweetener, which contains the same complex carbohydrates as brown rice syrup and a natural plant flavoring. -

Striped Bass in a Cumin and Mustard Seed Tomato Sauce, Topped With

Striped Bass in a Cumin and Mustard Seed Tomato Sauce, topped with Raw Tahini, !Zaatar Olive Oil, Garlic Scapes and Fresh Cilantro !*recipe by Athena Calderone & Eden Grinshpan !Ingredients • 2 fillets of striped bass, skins removed (you can substitute the striped bass with any fish) • 4 tablespoons olive oil • 2 tsp black mustard seeds • 1 tsp cumin seeds • 3 cloves of of garlic, finely chopped • 3 big tomatoes, medium chop • 1-2 tsp kosher salt • 1 pinch of sugar • 1 tsp red wine vinegar • 2-3 tablespoons raw tahini • Zaatar olive oil- 2 tablespoons of olive oil mixed with 1 tablespoon zaatar (if you cannot find zaatar, then just use 1 tsp toasted sesame seeds mixed with 1 tsp toasted cumin seeds crushed with a little olive oil) • 1 large handful of fresh cilantro to garnish • 3 garlic scapes, cut into 1/4 inch pieces- if you cannot find than just leave out • 1/2 lemon, juiced • 1 fresh white fluffy bread (I love using a fresh white pullman loaf) tear it instead of cutting for a ! really rustic affect !Directions Heat up 2 tablespoons of olive oil. Place in the mustard seeds and the cumin seeds. When the mustard seeds start to pop, add in the garlic, saute for a couple of seconds and then add in the tomatoes. Season with salt and a pinch of sugar. Saute for a couple of minutes and then add in the red wine vinegar, toss and let simmer for a couple more minutes to cook off the vinegar. Do not simmer for too long, you want the sauce to be chunky. -

21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–10 Edition) § 582.20

§ 582.20 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–10 Edition) Common name Botanical name of plant source Marjoram, sweet .......................................................................... Majorana hortensis Moench. Mustard, black or brown .............................................................. Brassica nigra (L.) Koch. Mustard, brown ............................................................................ Brassica juncea (L.) Coss. Mustard, white or yellow .............................................................. Brassica hirta Moench. Nutmeg ........................................................................................ Myristica fragrans Houtt. Oregano (oreganum, Mexican oregano, Mexican sage, origan) Lippia spp. Paprika ......................................................................................... Capsicum annuum L. Parsley ......................................................................................... Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Mansf. Pepper, black ............................................................................... Piper nigrum L. Pepper, cayenne ......................................................................... Capsicum frutescens L. or Capsicum annuum L. Pepper, red .................................................................................. Do. Pepper, white ............................................................................... Piper nigrum L. Peppermint .................................................................................. Mentha piperita L. Poppy seed