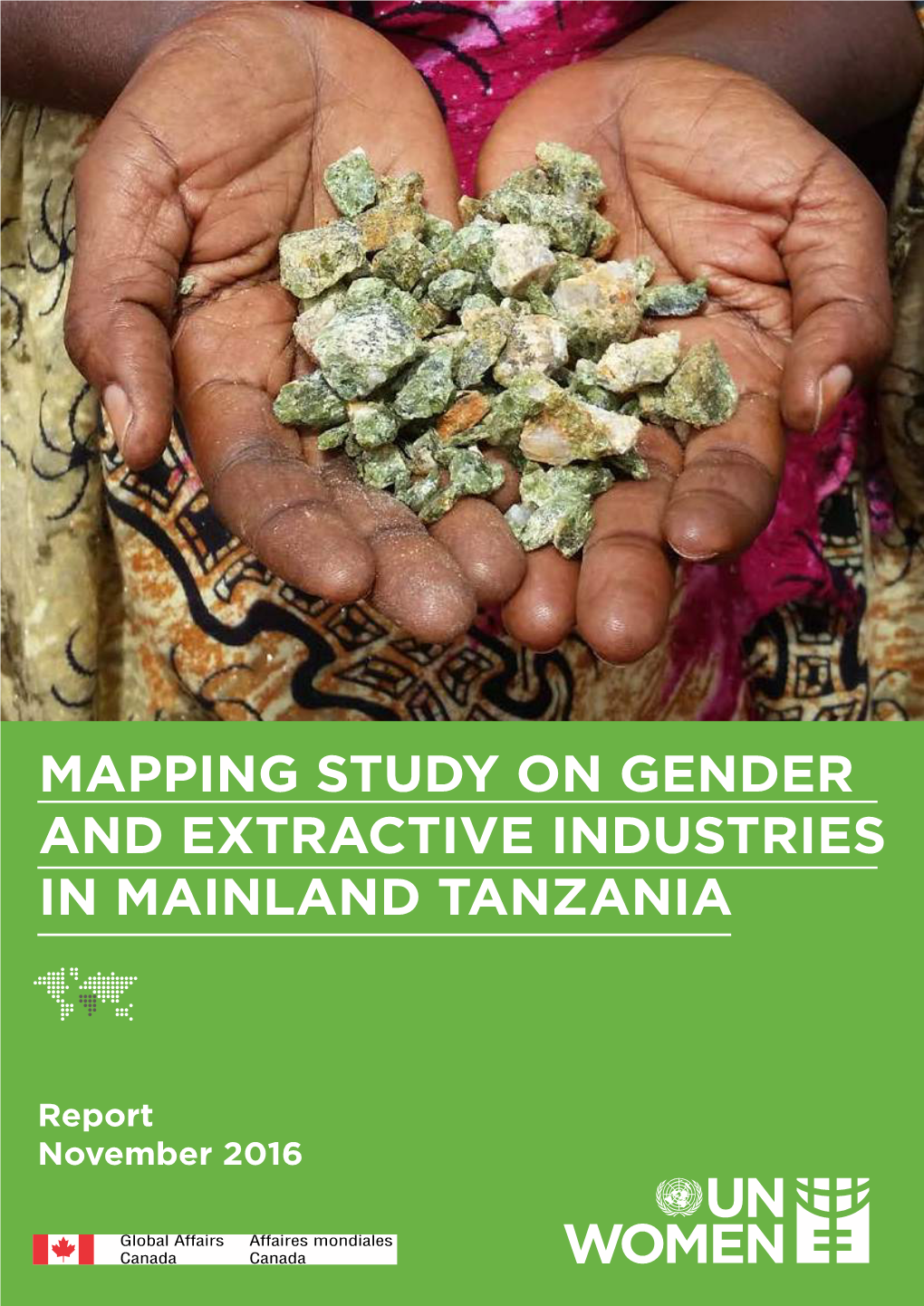

Mapping Study on Gender and Extractive Industries in Mainland Tanzania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

CA. 7h?F Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. P-3547-TA REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Public Disclosure Authorized ON A PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT CREDIT OF SDR 5.9 MILLION (AN AMOUNT EQUIVALENT TO US$6.3 MILLION) TO THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A COAL ENGINEERING PROJECT .May 2, 1983 Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = Tanzania Shilling (TSh) TSh 1.00 = US$0.11 US$1.00 = TSh 9.40 US$1.00 = SDR 0.927 (As the Tanzania Shilling is officially valued in relation to a basket of the currencies of Tanzania's trading partners, the USDollar/Tanzania Shilling exchange rate is subject to change. Conversions in this report were made at US$1.00 to TSh 9.40 which was the level set in the most recent exchange rate adjustment in March 1982. The USDollar/SDR exchange rate used in this report is that of March 31, 1983.) ABBREVTATIONS AND ACRONYMS CDC - Colonial (now Commonwealth) Development Corporation MOM - Ministry of Minerals MWE - Ministry of Water and Energy STAMICO - State Mining Corporation TANESCO - Tanzania Electric Supply Company TPDC - Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation toe - tonnes of oil equivalent tpy - tonnes per year FISCAL YEAR Government - July 1 to June 30 TrANZANIA FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Coal Engineering Project Credit and Project Summary Borrower: United Republic of Tanzania Beneficiary: Ministry of Minerals (MOM) and State, Mining Corporation (STAMICO) Amount: SDR 5.9 million (US$6.3 million equivalent) Terms: Standard Project Description: The project would support Government efforts ro evaluate the economic potential of the indigenous coal resources of Tanzania. -

2019 Tanzania in Figures

2019 Tanzania in Figures The United Republic of Tanzania 2019 TANZANIA IN FIGURES National Bureau of Statistics Dodoma June 2020 H. E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli President of the United Republic of Tanzania “Statistics are very vital in the development of any country particularly when they are of good quality since they enable government to understand the needs of its people, set goals and formulate development programmes and monitor their implementation” H.E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli the President of the United Republic of Tanzania at the foundation stone-laying ceremony for the new NBS offices in Dodoma December, 2017. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical information is very important as it helps a person to do things in an organizational way with greater precision unlike when one does not have. In my business, for example, statistics help me know where I can get raw materials, get to know the number of my customers and help me prepare products accordingly. Indeed, the numbers show the trend of my business which allows me to predict the future. My customers are both locals and foreigners who yearly visit the region. In June every year, I gather information from various institutions which receive foreign visitors here in Dodoma. With estimated number of visitors in hand, it gives me ample time to prepare products for my clients’ satisfaction. In terms of my daily life, Statistics help me in understanding my daily household needs hence make proper expenditures.” Mr. Kulwa James Zimba, Artist, Sixth street Dodoma.”. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical Data is useful for development at family as well as national level because without statistics one cannot plan and implement development plans properly. -

Governing Petroleum Resources Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania

Governing Petroleum Resources Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania Edited by Odd-Helge Fjeldstad • Donald Mmari • Kendra Dupuy Governing Petroleum Resources: Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania Edited by Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Donald Mmari and Kendra Dupuy Content Editors iv Acknowledgements v Contributors vi Forewords xi Abbreviations xiv Part I: Becoming a petro-state: An overview of the petroleum sector in Tanzania 1 Governing Petroleum Resources: 1. Petroleum resources, institutions and politics: An introduction to the book Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Donald Mmari and Kendra Dupuy 4 2. The evolution and current status of the petroleum sector in Tanzania Donald Mmari, James Andilile and Odd-Helge Fjeldstad 13 PART II: The legislative framework and fiscal management of the petroleum sector 23 3. The legislative landscape of the petroleum sector in Tanzania James Andilile, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Donald Mmari 26 4. An overview of the fiscal systems for the petroleum sector in Tanzania Donald Mmari, James Andilile, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Aslak Orre 35 5. Is the current fiscal regime suitable for the development of Tanzania’s offshore gas reserves? Copyright © Chr. Michelsen Institute 2019 James Andilile, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Donald Mmari and Aslak Orre 42 Copyright © Repoa 2019 6. Negotiating Tanzania’s gas future: What matters for investment and government revenues? Thomas Scurfield and David Manley 49 CMI 7. Uncertain potential: Managing Tanzania’s gas revenues P. O. Box 6033 Thomas Scurfield and David Mihalyi 59 N-5892 Bergen 8. Non-resource taxation in a resource-rich setting Norway Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Cornel Jahari, Donald Mmari and Ingrid Hoem Sjursen 66 [email protected] 9. -

Local Perceptions, Cultural Beliefs, Practices and Changing Perspectives of Handling Infant Feces: a Case Study in a Rural Geita District, North-Western Tanzania

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Local Perceptions, Cultural Beliefs, Practices and Changing Perspectives of Handling Infant Feces: A Case Study in a Rural Geita District, North-Western Tanzania Joy J. Chebet 1,*, Aminata Kilungo 1,2, Halimatou Alaofè 1, Hamisi Malebo 3, Shaaban Katani 3 and Mark Nichter 1,4 1 Department of Health Promotion Sciences, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (H.A.); [email protected] (M.N.) 2 Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA 3 National Institute for Medical Research, 11101 Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; [email protected] (H.M.); [email protected] (S.K.) 4 Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 April 2020; Accepted: 25 April 2020; Published: 29 April 2020 Abstract: We report on the management of infant feces in a rural village in Geita region, Tanzania. Findings discussed here emerged incidentally from a qualitative study aimed at investigating vulnerability and resilience to health challenges in rural settings. Data was gathered through semi-structured focus group discussions (FDGs) with women (n = 4; 32 participants), men (n = 2; 16 participants), and community leaders (n = 1; 8 participants). All FDGs were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematically analyzed using Atlas.ti. Respondents reported feces of a child under the age of six months were considered pure compared to those of older children. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 5/Friday, January 8, 2021/Notices

1560 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 5 / Friday, January 8, 2021 / Notices The Interest Rates are: 409 3rd Street SW, Suite 6050, system determined by the President to Washington, DC 20416, (202) 205–6734. meet substantially the standards, Percent SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The notice practices, and procedures of the KPCS. of an Administrative declaration for the The referenced regulations are For Physical Damage:. contained at 31 CFR part 592 (‘‘Rough Homeowners With Credit Avail- State of California, dated 06/17/2020, is able Elsewhere ...................... 2.375 hereby amended to establish the Diamond Control Regulations’’) (68 FR Homeowners Without Credit incident period for this disaster as 45777, August 4, 2003). Available Elsewhere .............. 1.188 beginning 05/26/2020 and continuing Section 6(b) of the Act requires the Businesses With Credit Avail- through 12/28/2020. President to publish in the Federal able Elsewhere ...................... 6.000 All other information in the original Register a list of all Participants, and all Businesses Without Credit declaration remains unchanged. Importing and Exporting Authorities of Available Elsewhere .............. 3.000 Participants, and to update the list as Non-Profit Organizations With (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance Number 59008) necessary. Section 2 of Executive Order Credit Available Elsewhere ... 2.750 13312 of July 29, 2003 delegates this Non-Profit Organizations With- Jovita Carranza, function to the Secretary of State. out Credit Available Else- Administrator. where ..................................... 2.750 Section 3(7) of the Act defines For Economic Injury:. [FR Doc. 2021–00169 Filed 1–7–21; 8:45 am] ‘‘Participant’’ as a state, customs Businesses & Small Agricultural BILLING CODE 8026–03–P territory, or regional economic Cooperatives Without Credit integration organization identified by Available Elsewhere ............. -

The Linking Initiatives for Elimination of Pediatric HIV (LIFE) Program

The Linking Initiatives for Elimination of Pediatric HIV (LIFE) Program END OF PROJECT REPORT | 2012-2016 The production of this program brief was made possible through support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The contents of this brief do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of USAID. Cover photo: Nigel Barker/EGPAF, 2009 2 Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation - TanzaniaUnless stated otherwise, all photos: Daniel Hayduk/EGPAF, 2016 Table of Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................4 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................6 Current State of HIV in Tanzania ..................................................................................8 EGPAF-Tanzania ........................................................................................................10 EGPAF-supported Approaches .............................................................................11 LIFE ...........................................................................................................................12 Goal and Objectives .............................................................................................14 LIFE Results by Objectives ..........................................................................................15 Objective 1: Comprehensive HIV and RCH Services -

Background of Community-Based Conservation

Beyond Community: "Global" Conservation Networks and "Local" Organization in Tanzania and Zanzibar Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Dean, Erin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 01:23:33 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195624 BEYOND COMMUNITY: “GLOBAL” CONSERVATION NETWORKS AND “LOCAL” ORGANIZATION IN TANZANIA AND ZANZIBAR by Erin Dean _____________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2007 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by ERIN DEAN entitled BEYOND COMMUNITY: "GLOBAL" CONSERVATION NETWORKS AND "LOCAL" ORGANIZATION IN TANZANIA AND ZANZIBAR and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: August 14, 2007 Diane Austin _______________________________________________________________________ Date: August 14, 2007 Mamadou Baro _______________________________________________________________________ -

Prospectus 2016/2017

MINERAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE (MRI) P. O. Box 1696, Dodoma, Tanzania Telephone/Fax: +255 (0) 26 23 00 472 / +255 (0) 26 23 03 159 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Website: www.mri.ac.tz PROSPECTUS 2016/2017 August, 2016 Prospectus 2016/2017 i FORWORD We are very pleased to welcome you to undertake tertiary studies at The Mineral Resources Institute (MRI). This Prospectus will provide you with a flavour of academic life in our Institution. The Mineral Resources Institute (MRI) is an institution of Earth Sciences Education which was established by the former Ministry of Minerals in Dodoma in August, 1982. It is fully accredited by the National Council for Technical Education (NACTE) to offer Geology and Mineral Exploration, mining engineering, Petroleum Geoscience, Mineral Processing Engineering and Environmental Engineering and Management in Mines programmes leading to the qualifications of National Technical Awards (NTA) level 4 – 6. NTA level 4 programmes lead to Basic Technician Certificate, NTA level 5 programme lead to Technician Certificate and NTA level 6 programme lead to Ordinary Diploma Certificate. Along with the introduction of the new curricula, the previous curricula leading to Mineral Resources Technology Certificate and Full Technician Certificate in Earth Sciences have already been phased out. With the cooperation of main stakeholders under the auspices of the Ministry of Energy and Minerals (MEM), the Institute is still undergoing transformation to match with the envisaged expectations and aspirations of the Tanzania. Our ultimate goal is to transform our institution to be the best academic institution in Africa in 25 years from 2012 in areas of quality training in mining sector including gemology and petroleum sciences; quality research in geological sciences and mining related sciences and quality consultancy and provisional of sound short courses. -

A Study on the Sustainability and the Aftermaths of the HESAWA Project in Tanzania

2013-06-12 A study on the sustainability and the aftermaths of the HESAWA project in Tanzania Sara Andersson School of Social Sciences Peace and Development Studies 2FU31E - 1003 Bachelor Thesis Tutor: Jonas Ewald Sara Andersson Peace and Development Studies 2013-06-12 Bachelor Thesis Linnaeus University Abstract: The Health through Sanitation and Water project (HESAWA) was first initiated in 1983/84, and was implemented from 1985 to 2002. The project covered three regions in northwestern Tanzania and strived towards improving the health situation in the area through improvements in the water and sanitation sector, as well as by providing health education to the local people. The aim of this research study is to investigate if the HESAWA project and its implemented structures have been sustainable for the local population in the affected villages in the Geita region in Tanzania. The Sida evaluation manual, Looking Back, Moving Forward, has been used as an analytical frame of interpretation to determine if these goals have been fulfilled. The research was carried out as a fieldstudy in two villages in the Geita and Mwanza region, just south of Lake Victoria. In total 42 interviews were conducted among families, Water Committees, focus groups of men and women, dispensaries, health clinics, schools, NGOs, and former HESAWA workers. The questions were centered on water, sanitation, and health issues. The most common diseases included diarrhea, bilharzia, worms, and malaria. Even though these diseases have decreased in the area, they are still present to a large extent. The conclusion drawn from this study is that the HESAWA project did make a difference in the Geita region. -

A Multi-Agency Task Team Working Together to End Destructive Blast Fishing

Fiche 33 by © IOC-SmartFish© A Multi-Agency Task Team Working together to end destructive blast fishing Background The story Blast fishing, also known as dynamite fishing, is a highly Many factors contribute to the prevalence of blast fishing in destructive, illegal method of catching fish which uses dynamite Tanzania; the low cost and easy accessibility of explosives or other types of explosives to send shock-waves through the from the mining sector, road construction projects and water, stunning or killing fish which are then collected and sold. cement factories; the relatively easy methods of making Blast fishing can be lucrative: both from the sale of the fish home-made explosives using simple ingredients such as a caught and also from the trade of illegal explosives. Improvised plastic bottle filled with chemical fertilizers and diesel; the explosive devices may explode prematurely and have been low and ineffective rate of enforcement and prosecutions; known to injure or kill the person using them, or innocent environmental stresses resulting in reduced catches by bystanders. traditional fishing methods; and the high levels of poverty and unemployment. Blast fishing was first recorded in Africa in the early 1960s and while it has been brought under control in neighbouring Law enforcement is severely hampered by corruption of some countries it remains a huge problem in Tanzania. Blast fishing officials who tip off blast fishers about patrols, and intimidation occurs along the entire Tanzanian coastline and often takes of officials and the local community who fear the consequences place within the coral reefs, biodiversity hotspots that provide of informing on blast fishers1 . -

Accelerating Mini-Grid Deployment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Tanzania I Design and Layout By: Jenna Park [email protected] TABLE of CONTENTS

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ACCELERATING MINI- GRID DEPLOYMENT IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA Lessons from Tanzania Public Disclosure Authorized LILY ODARNO, ESTOMIH SAWE, MARY SWAI, MANENO J.J. KATYEGA AND ALLISON LEE Public Disclosure Authorized WRI.ORG Accelerating Mini-Grid Deployment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Tanzania i Design and layout by: Jenna Park [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Foreword 3 Preface 5 Executive Summary 13 Introduction 19 Overview of Mini-Grids in Tanzania 39 The Institutional, Policy, and Regulatory Framework for Mini-Grids in Tanzania 53 Mini-Grid Ownership and Operational Models 65 Planning and Securing Financing for Mini-Grid Projects 79 How Are Mini-Grids Contributing to Rural Development? 83 Conclusions and Recommendations 86 Appendix A: People Interviewed for This Report 88 Appendix B: Small Power Producers That Signed Small Power Purchase Agreements and Submitted Letters of Intent 90 Appendix C: Policies, Strategies, Acts, Regulations, Technical Standards, and Programs, Plans, and Projects on Mini-Grids 94 Abbreviations 95 Glossary 96 Bibliography 99 Endnotes Accelerating Mini-Grid Deployment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Tanzania iii iv WRI.org FOREWORD More than half of the 1 billion people in the world In Tanzania, a slow environmental clearance without electricity live in Sub-Saharan Africa, procedure delayed the deployment of some mini- and rapid population growth is projected to grids despite a streamlined regulatory process. outpace electric grid expansion. For communities across the region, a consistent and affordable Invest in both qualitative and quantitative ▪ supply of electricity can open new possibilities for assessments of the development impacts socioeconomic progress. -

3052 Geita District Council

Council Subvote Index 63 Geita Region Subvote Description Council District Councils Number Code 2035 Geita Town Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children 5031 Salaries for VEOs 5033 Agriculture 5034 Livestock 5036 Environments 3052 Geita District Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children 5031 Salaries for VEOs 5033 Agriculture 5034 Livestock 3090 Bukombe District Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services ii Council Subvote Index 63 Geita Region Subvote Description Council District Councils Number Code 3090 Bukombe District Council 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children