JDI Brazil and Tanzania Report Fall 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Lot Value = $8,189.80 LOT #128 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $8,189.80 LOT #128 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A07-S05-D001 128 182363 TICB-1001 $13.95 16G 5/16" Internally Threaded Implant Grade Titanium Curved Barbell 8 Curved Barbell $111.60 A07-S05-D003 128 186942 NR-1316 $8.95 Purple 2mm Bezel-Set Synthetic Opal Rose Gold-Tone Steel Nose Ring Twist 1 Nose Ring $8.95 A07-S05-D005 128 65492 A208 $11.99 Celtic Swirl Reverse Belly Button Ring 4 Belly Ring Sale $47.96 A07-S05-D006 128 104247 PLG-1345-14 $10.95 9/16" Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs Pair 4 Plugs $43.80 A07-S05-D007 128 65494 D103 $5.95 16G 3/8 - Anodized Rainbow Titanium-Plated Captive Bead Ring 3 Captive Ring , Daith $17.85 A07-S05-D008 128 65496 D103b $5.95 Rainbow Titanium-Plated Captive Bead Ring - 14G 1/2 1 Captive Ring $5.95 A07-S05-D010 128 65499 D103d $4.99 16G 5/8 - Rainbow Anodized Steel Captive Bead Ring 51 Captive Ring $254.49 A07-S05-D011 128 87697 BR-1429 $11.99 Pink CZ Crown & Flower Dangle Belly Button Navel Ring 2 Belly Ring Sale $23.98 A07-S05-D012 128 64066 BR-1496 $11.99 Purple CZ Crown & Flower Dangle Belly Button Navel Ring 4 Belly Ring Sale $47.96 A07-S05-D013 128 65502 D111 $5.99 Spiky -Ball Twister - Body Jewelry 14 Gauge 43 Twister Barbell Sale $257.57 A07-S05-D014 128 104271 PLG-1345-16 $10.95 5/8" - Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs - Pair 2 Plugs $21.90 A07-S05-D015 128 104185 PLG-1345-4 $8.95 6G - Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs - Pair 2 Plugs $17.90 -

World Bank Document

CA. 7h?F Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. P-3547-TA REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Public Disclosure Authorized ON A PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT CREDIT OF SDR 5.9 MILLION (AN AMOUNT EQUIVALENT TO US$6.3 MILLION) TO THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A COAL ENGINEERING PROJECT .May 2, 1983 Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = Tanzania Shilling (TSh) TSh 1.00 = US$0.11 US$1.00 = TSh 9.40 US$1.00 = SDR 0.927 (As the Tanzania Shilling is officially valued in relation to a basket of the currencies of Tanzania's trading partners, the USDollar/Tanzania Shilling exchange rate is subject to change. Conversions in this report were made at US$1.00 to TSh 9.40 which was the level set in the most recent exchange rate adjustment in March 1982. The USDollar/SDR exchange rate used in this report is that of March 31, 1983.) ABBREVTATIONS AND ACRONYMS CDC - Colonial (now Commonwealth) Development Corporation MOM - Ministry of Minerals MWE - Ministry of Water and Energy STAMICO - State Mining Corporation TANESCO - Tanzania Electric Supply Company TPDC - Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation toe - tonnes of oil equivalent tpy - tonnes per year FISCAL YEAR Government - July 1 to June 30 TrANZANIA FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Coal Engineering Project Credit and Project Summary Borrower: United Republic of Tanzania Beneficiary: Ministry of Minerals (MOM) and State, Mining Corporation (STAMICO) Amount: SDR 5.9 million (US$6.3 million equivalent) Terms: Standard Project Description: The project would support Government efforts ro evaluate the economic potential of the indigenous coal resources of Tanzania. -

Governing Petroleum Resources Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania

Governing Petroleum Resources Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania Edited by Odd-Helge Fjeldstad • Donald Mmari • Kendra Dupuy Governing Petroleum Resources: Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania Edited by Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Donald Mmari and Kendra Dupuy Content Editors iv Acknowledgements v Contributors vi Forewords xi Abbreviations xiv Part I: Becoming a petro-state: An overview of the petroleum sector in Tanzania 1 Governing Petroleum Resources: 1. Petroleum resources, institutions and politics: An introduction to the book Prospects and Challenges for Tanzania Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Donald Mmari and Kendra Dupuy 4 2. The evolution and current status of the petroleum sector in Tanzania Donald Mmari, James Andilile and Odd-Helge Fjeldstad 13 PART II: The legislative framework and fiscal management of the petroleum sector 23 3. The legislative landscape of the petroleum sector in Tanzania James Andilile, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Donald Mmari 26 4. An overview of the fiscal systems for the petroleum sector in Tanzania Donald Mmari, James Andilile, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Aslak Orre 35 5. Is the current fiscal regime suitable for the development of Tanzania’s offshore gas reserves? Copyright © Chr. Michelsen Institute 2019 James Andilile, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Donald Mmari and Aslak Orre 42 Copyright © Repoa 2019 6. Negotiating Tanzania’s gas future: What matters for investment and government revenues? Thomas Scurfield and David Manley 49 CMI 7. Uncertain potential: Managing Tanzania’s gas revenues P. O. Box 6033 Thomas Scurfield and David Mihalyi 59 N-5892 Bergen 8. Non-resource taxation in a resource-rich setting Norway Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Cornel Jahari, Donald Mmari and Ingrid Hoem Sjursen 66 [email protected] 9. -

Distinctive Designs

Distinctive Designs Brides Ring in an Era of Self-Expression by Stacey Marcus Diamond rings have been sporting the hands of newly can elevate a traditional setting to an entirely new level. While engaged women since ancient times. In the mid 1940s, diamonds are always in vogue for engagement rings, millen- DeBeers revived the ritual with its famous “Diamonds Are nials are also opting for nontraditional stones, such as color- Forever” campaign. Today’s brides are blazing new trails by changing alexandrite, beautiful tanzanite, black opal, and even selecting nontraditional wedding rings that express their aquamarine. We are in an age when anything goes, and brides individual style. are embracing the idea of individuality and self-expression!” True Colors says Jordan Fine, CEO of JFINE. “Brides today want to be unique and they don’t mind taking Kathryn Money, vice president of strategy and merchandising chances with colors, settings, and stones. When it comes to at Brilliant Earth agrees: “Customers are seeking products that choosing an engagement ring, natural pink, blue, and even express their individuality and are increasingly drawn towards green diamonds are trending. These precious and rare dia- uniqueness. They want a ring that isn’t like everyone else’s, monds originate from only a few mines in the world, and they which we’re seeing manifested in many different ways, such 34 Spring 2018 BRIDE&GROOM as choosing a distinctive ring setting, using colored gemstones in lieu of a diamond, using a fancy (non-round) diamond, or opting for rose gold.” Money adds that 16% of respondents in a recent survey they conducted favored a colored gemstone engagement ring over a diamond. -

MAGAZINE • LEAWOOD, KS SPECIAL EDITION 2016 ISSUE 3 Fine Jewelers Magazine

A TUFTS COMMUNICATIONS fine jewelry PUBLICATION MAZZARESE MAGAZINE • LEAWOOD, KS SPECIAL EDITION 2016 ISSUE 3 fine jewelers magazine Chopard: Racing Special The New Ferrari 488 GTB The Natural Flair of John Hardy Black Beauties Omega’s New 007 SPECIAL EDITION 2016 • ISSUE 3 MAZZARESE FINE JEWELERS MAGAZINE • SPECIAL EDITION 2016 welcome It is our belief that we have an indelible link with the past and a responsibility to the future. In representing the fourth generation of master jewelers and craftsmen, and even as the keepers of a second generation family business, we believe that the responsibility to continually evolve and develop lies with us. We endeavor to always stay ahead of the latest jewelry and watch trends and innovations. We stay true to our high standards and objectives set forth by those that came before us by delivering a jewelry experience like no other; through the utmost attention to service, knowledge and value. Every great story begins with a spark of inspiration. We are reminded day after day of our spark of inspiration: you, our esteemed customer. Your stories help drive our passion to pursue the finest quality pieces. It is a privilege that we are trusted to provide the perfect gift; one that stands the test of time and is passed along through generations. We find great joy in assisting the eager couple searching for the perfect engagement ring, as they embark on a lifetime of love, helping to select a quality timepiece, or sourcing a rare jewel to mark and celebrate a milestone. We are dedicated to creating an experience that nurtures relationships and allows those who visit our store to enter as customers, but leave as members of our family. -

Murostar-Katalog-2018-2019.Pdf

Material B2B Großhandel für Piercing- und Tattoo- B2B Wholesale for body piercing and Unsere Qualität ist Ihre Zufriedenheit Our quality is your satisfaction About Us studios, sowie Schmuck- und Juwelier- tattoo studios as well as jewelry stores vertriebe Oberste Priorität hat bei uns die reibungslose Abwicklung Our top priority is to provide a smooth transaction and fast Titan Produkte entsprechen dem Grad 23 (Ti6AL 4V Eli) und Titanium products correspond to titanium grade 23 (Ti6Al und schnelle Lieferung Ihrer Ware. Daher verlassen ca. 95 % delivery. Therefore, approximately 95% of all orders are sind generell hochglanzpoliert. Sterilisierbar. 4V Eli) and are generally high polished. For sterilization. aller Aufträge unser Lager noch am selben Tag. shipped out on the same day. Black Titan besteht grundsätzlich aus Titan Grad 23 (Ti6AL Black Titanium is composed of titanium grade 23 (Ti6Al 4V Unser dynamisches, kundenorientiertes Team sowie ausge- Our dynamic, customer-oriented team and excellent expe- 4V Eli) und ist zusätzlich mit einer PVD Titanium Beschich- Eli) and is additionally equipped with a PVD Black Titanium zeichnete Erfahrungswerte garantieren Ihnen einen hervor- rience guarantee excellent service and expert advice. tung geschwärzt. Sterilisierbar. Coating. For sterilization. ragenden Service und kompetente Beratung. Steel Schmuck besteht grundsätzlich aus Chirurgenstahl Steel jewelry is composed of 316L Surgical Steel and is also Sie bestellen schnell und unkompliziert online, telefo- Your order can be placed quickly and easily online, by 316L und ist ebenfalls hochglanzpoliert. Sterilisierbar. high polished. For sterilization. nisch, per Fax oder Email mittels unseres einfachen Ex- phone, fax or email using our simple Express Number press-Nummern-Systems ohne Angabe von Farb- oder Grö- System only without providing colors or sizes. -

Gem Wealth of Tanzania GEMS & GEMOLOGY Summer 1992 Fipe 1

By Dona M.Dirlarn, Elise B. Misiorowski, Rosemaiy Tozer, Karen B. Stark, and Allen M.Bassett The East African nation of Tanzania has he United Republic of Tanzania, the largest of the East great gem wealth. First known by Western- 1African countries, is composed of mainland Tanzania and ers for its diamonds, Tanzania emerged in the island of Zanzibar. 1t is regarded by many as the birthplace the 1960s as a producer of a great variety of of the earliest ancestors of Homo sapiens. To the gem indus- other gems such as tanzanite, ruby, fancy- try, however, Tanzania is one of the most promising fron- colored sapphire, garnet, and tourmaline; to date, more than 50 gem species and vari- tiers, with 50 gem species and varieties identified, to date, eties have been produced. As the 1990s from more than 200 occurrences. begin, De Beers has reinstated diamond "Modem" mining started in the gold fields of Tanzania in exploration in Tanzania, new gem materials the late 1890s (Ngunangwa, 19821, but modem diamond min- such as transparent green zoisite have ing did not start until 1925, and nearly all mining of colored appeared on the market, and there is stones has taken place since 1950. Even so, only a few of the increasing interest in Tanzania's lesser- gem materials identified have been exploited to any significant known gems such as scapolite, spinel, and extent: diamond, ruby, sapphire, purplish blue zoisite (tan- zircon. This overview describes the main zanite; figure l),and green grossular [tsavorite)and other gar- gems and gem resources of Tanzania, and nets. -

Guaranteed Shops Ocho Rios

DI_AD_PPI_110212.pdf 1 11/2/2012 12:48:01 PM GUARANTEED SHOPS OCHO RIOS SHOP SCAN SHOP&SCAN ACTIVATE YOUR SHOPPING GUARANTEE INTERNATIONAL LUXURY BRANDS Forevermark Diamonds • Tanzanite International Hearts On Fire Diamonds • Jewels & Time C M Y DESIGNER BRANDS CM MY Alex and Ani Jewelry • Jewels & Time CY Ammolite Jewelry by Korite • Tanzanite International CMY Crown of Light Diamonds • Tanzanite International K Ernst Benz Watches • Jewels & Time Fruitz Watches • Jewels & Time Gift Diamond Jewelry • Tanzanite International Glam Rock Watches • Jewels & Time John Hardy Jewelry • Jewels & Time Kabana Jewelry • Tanzanite International Mark Henry Alexandrite Jewelry • Jewels & Time Movado Watches • Tanzanite International Parazul Handbags & Accessories • Jewels & Time Philip Stein Watches • Jewels & Time Safi Kilima Tanzanite Jewelry• Tanzanite International AT A GLANCE IN CASE OF EMERGENCY PORT & SHOPPING Capital: Kingston Lannaman & Morris (Shipping) Ltd. CHANNEL Location: 90 miles south of Cuba Ocho Rios Cruise Ship Terminal Tune in to the Port Channel for the latest Taxi: Taxis are available P.O. Box 201 Ocho Rios updated port and shopping information. Currency: Jamaican dollar St. Ann Jamaica PORT SHOPPING BUYER’S GUARANTEE Consult your Freestyle Daily for Language: English, Sharon Snape The Port Shopping Program is operated by The PPI Group and the stores listed on this map and mentioned in the Port & Shopping Presentations have paid an advertising fee to promote shopping channel listing. opportunities ashore. These stores provide a 30-day guarantee after purchase to Norwegian Cruise Line’s guests. This guarantee is valid for repair or exchange. Buyer’s negligence and buyer’s English-based patois Tel: (876) 974-5681 / 974-2983 remorse are excluded from the guarantee. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 5/Friday, January 8, 2021/Notices

1560 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 5 / Friday, January 8, 2021 / Notices The Interest Rates are: 409 3rd Street SW, Suite 6050, system determined by the President to Washington, DC 20416, (202) 205–6734. meet substantially the standards, Percent SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The notice practices, and procedures of the KPCS. of an Administrative declaration for the The referenced regulations are For Physical Damage:. contained at 31 CFR part 592 (‘‘Rough Homeowners With Credit Avail- State of California, dated 06/17/2020, is able Elsewhere ...................... 2.375 hereby amended to establish the Diamond Control Regulations’’) (68 FR Homeowners Without Credit incident period for this disaster as 45777, August 4, 2003). Available Elsewhere .............. 1.188 beginning 05/26/2020 and continuing Section 6(b) of the Act requires the Businesses With Credit Avail- through 12/28/2020. President to publish in the Federal able Elsewhere ...................... 6.000 All other information in the original Register a list of all Participants, and all Businesses Without Credit declaration remains unchanged. Importing and Exporting Authorities of Available Elsewhere .............. 3.000 Participants, and to update the list as Non-Profit Organizations With (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance Number 59008) necessary. Section 2 of Executive Order Credit Available Elsewhere ... 2.750 13312 of July 29, 2003 delegates this Non-Profit Organizations With- Jovita Carranza, function to the Secretary of State. out Credit Available Else- Administrator. where ..................................... 2.750 Section 3(7) of the Act defines For Economic Injury:. [FR Doc. 2021–00169 Filed 1–7–21; 8:45 am] ‘‘Participant’’ as a state, customs Businesses & Small Agricultural BILLING CODE 8026–03–P territory, or regional economic Cooperatives Without Credit integration organization identified by Available Elsewhere ............. -

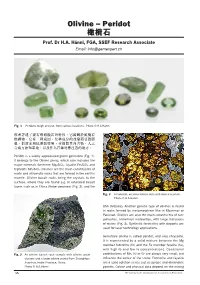

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof. Dr H.A. Hänni, FGA, SSEF Research Associate Email: [email protected] Fig. 1 Peridots rough and cut, from various locations. Photo © H.A.Hänni 作者述了寶石級橄欖石的特性,它歸屬於橄欖石 類礦物,它有三種成因,化學成的改變而引致顏 色、折射率和比重的變異,並簡報其內含物、人工 合成方法和產地,以及作為首飾時應注意的地方。 Peridot is a widely appreciated green gemstone (Fig. 1). It belongs to the Olivine group, which also includes the major minerals forsterite Mg2SiO4, fayalite Fe2SiO4 and tephroite Mn2SiO4. Olivines are the main constituents of maic and ultramaic rocks that are formed in the earth’s mantle. Olivine-basalt rocks bring the crystals to the surface, where they are found e.g. in extended basalt layers such as in China (Hebei province) (Fig. 2), and the Fig. 3 A Pallasite, an iron-nickel matrix with olivine crystals. Photo © H.A.Hänni USA (Arizona). Another genetic type of olivines is found in rocks formed by metamorphism like in Myanmar or Pakistan. Olivines are also the main constituents of rare pallasites, nickel-iron meteorites, with large inclusions of olivine (Fig. 3). Synthetic forsterites with dopants are used for laser technology applications. Gemstone olivine is called peridot, and also chrysolite. It is represented by a solid mixture between the Mg member forsterite (fo) and the Fe member fayalite (fa), with high fo and low fa concentrations. Occasional Fig. 2 An olivine-basalt rock sample with olivine grain contributions of Mn, Ni or Cr are always very small, but clusters and a larger olivine crystal from Zhangjikou- inluence the colour of the stone. Forsterite and fayalite Xuanhua, Hebei Province, China. are a solid solution series just as pyrope and almandine Photo © H.A.Hänni garnets. -

Global Extractivism and Mining Resistance in Brazil and India

Revised Pages Iron Will Revised Pages Revised Pages Iron Will Global Extractivism and Mining Resistance in Brazil and India Markus Kröger University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2020 by Markus Kröger All rights reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Note to users: A Creative Commons license is only valid when it is applied by the person or entity that holds rights to the licensed work. Works may contain components (e.g., photographs, illustrations, or quotations) to which the rightsholder in the work cannot apply the license. It is ultimately your responsibility to independently evaluate the copyright status of any work or component part of a work you use, in light of your intended use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published November 2020 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN 978-0-472-13212-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12711-5 (e-book) ISBN 978-0-472-90239-2 (OA) http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11533186 Revised Pages To Otso and Jenni Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 Part I. Theorizing the Impacts of Resistance to Extractivism 25 Chapter 1. Resistance and Investment Outcomes 27 Chapter 2. -

Introduction Anthropology and Knowledge Production in a ‘Minefield’

Dossier “Mining, violence and resistance” Introduction Anthropology and knowledge production in a ‘minefield’ Andréa Zhouri Departamento de Antropologia e Arqueologia, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil In 2003, when Chris Ballard and Glenn Banks updated – and upgraded – Ricardo Godoy’s call for a systematization of an Anthropology of Mining (1985), they simultaneously warned: “mining is no ethnographic playground”. Focused mainly in situations across the Asia-Pacific region, the review questioned the often monolithic “characterizations of state, corporate, and community forms of agency” and charted the debate among anthropologists involved in mining about the appropriate terms of their engagement - as consultants, researchers and advocates. Differently from the context analyzed by Godoy in the mid-1980s, the authors emphasized the novel and complex scope of mining activities, particularly the interplay of actors involved in large-scale hard-rock mines in the new millennium, ranging from local to global players: that is, indigenous peoples, local communities, state agencies, transnational corporations, national and transnational NGOs, social and environmental movements, international institutions, among others. Each of these actors has a different agenda, scope of actions and quantum of power at the mining sites. Ballard and Banks, drawing on Gedicks’ (1993) “resource wars”,1 pointed out the context of conflict typical of mining settings and the necessary considerations of the position of Anthropologists within these. Such a warning is still relevant and reverberates in a rather more diverse and complex manner today, considering the current forms of neoextractivisms, which interlace high technology, the international division of labor and capital, the advances over new frontiers and, above all, the aggravation of mining’s spillage effects (Gudynas 2016)2.