Iranian American Intergenerational Narratives and the Complications of Racial & Ethnic Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MONA News Connection, You May Submit Them Via E-Mail to [email protected]

December 2017 All three ethnic commissions collaborated to put on the gala and for the first time, held a joint commission Building unity meeting where MAPAAC, CMEAA, and HLCOM and creating commission chairs presented their vision and mission to opportunity was Lt. Gov. Brian Calley and held a question and answer the theme of session. The meeting also gave the commissioners a the first annual chance to connect and brainstorm on issues in their New Americans respective communities. Appreciation Gala, which The Michigan International Talent Solutions (MITS) featured Gov. program also expanded its efforts to place New Rick Snyder as Americans in jobs across the state, by working with its keynote those in the private sector and helping them connect to speaker. Six New American business owners were New American talent. MITS will continue its growth as a given the New Americans Leadership award, program by bridging the gap between employers and presented by Gov. Snyder and the Chairpersons of New American talent. each Ethnic Commissions, Noel Garcia Jr. of HLCOM, Jamie Hsu of MAPAAC and Manal Saab As I reflect on 2017 and all the important things MONA of CMEAA. and its partners have achieved and collaborated on, I am confident that MONA will continue to successfully The awardees: were: Elizabeth Rosario of Grand serve its constituents. MONA will continue its Rapids Law Group, PLLC; Frank Venegas Jr. of commitment to collaboration and focus on expanding Ideal Group, Chain Sandhu of NYX, Inc., Ravinder partnerships across the state. MONA will continue “Ron” Shahani of Acro Service Corp.; Mary Shaya utilizing all resources to place New Americans in jobs of J&B Medical Supply and Mohamed Sohoubah of that help not only grow the Michigan economically but Biomed Specialty Pharmacy. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Anesthesia and Pain Management in Traditional Iranian Medicine

Pregledni rad Acta Med Hist Adriat 2016; 14(2);317-326 Review article ANESTHESIA AND PAIN MANAGEMENT IN TRADITIONAL IRANIAN MEDICINE ANESTEZIJA I UPRAVLJANJE BOLI U TRADICIONALNOJ IRANSKOJ MEDICINI Alireza Salehi, Faranak Alembizar, Ayda Hosseinkhani* Summary Studying the history of science could help develop an understanding of the contributions made by ancient nations towards scientific advances. Although Iranians had an import- ant impact on the improvement of science, the history of Iranian medicine seems not to have been given enough attention by historians. The present study focused on the history of anes- thesia and pain management in Iranian medical history. In this regard, related books such as Avesta and Shahnameh were studied in order to obtain the history of anesthesiology in Iranian pre Islamic era. This subject was also studied in the famous books of Rhazes, Haly Abbas, Avicenna, Jorjani, MomenTunekaboni and Aghili from different times of the Islamic era. Scientific data bases such as PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar were searched using key words “Iranian”, “Persian”, “pain management” and “anesthesia”. It was discovered that pain management and anesthesiology were well known to the Iranians. Rhazes and Avicenna had innovations in this regard. Fourteen Mokhader (anesthetic) herbs, which were included in the collection of the previous knowledge of the 18th century entitled Makhzan al-Advieyh and used as the Persian Materia Medica, were identified and listed. This study introduces the history of anesthesiology and pain management at different periods in the history of Iran. Key words: Anesthesiology; pain management; traditional Iranian medicine. * Research centre for traditional medicine and history of medicine, Shiraz University of medical sciences Shiraz, Iran. -

Achaemenid Empire/ (Persia) BY: HOZAN LATIF RAUF General Architectural Features

Achaemenid Empire/ (Persia) BY: HOZAN LATIF RAUF General Architectural features ▪ The architecture of Persians was more columnar and that led to vastly different massive architectural features from that of the Mesopotamian era. ▪ The use of flat timber roofs rather than vaults led to more slender columns and were rather more beautiful. This also led to rooms being squarer in shape than simple long rectangle. ▪ The roofing system was also very different, wherein the wooden brackets were covered in clay and provided more stability. The use of a double mud wall might have provided room for windows just below ceiling in structures like Palace of Persepolis. VOCABULARY WORDS ▪ The COLUMN is divided into three parts: ▪ The BASE ▪ The SHAFT- FLUTED ▪ The CAPITAL- Double Animal most with bulls Ancient Susa/Shush The city of SUSA was the Persian capital in succession to Babylon, where there is a building with a citadel complex. There was a good skill set of artisans and laborers available which made the palace complex more of a piece of art than just a building structure. Cedar wood was got from Lebanon and teak from the mountain of Zagros. The baked bricks were still made in the Babylonian method. Ancient Susa/Shush Ancient Persepolis PERSEPOLIS ▪ 518 BCE ▪ King Darius utilized influences and materials from all over his empire, which included Babylon, Egypt, Mesopotamian and Greece Architectural Plan of Ancient Persepolis The Great/Apadana Staircase ▪ King Xerxes (486-465 BC) built the Grand Staircase and the Gate of All Nations. ▪ The Grand Staircase is located on the northeast side of the city and these stairs were carved from massive blocks of stone. -

A Century of Armenians in America

A Century of Armenians in America: Voices from New Scholarship The Armenian Center at Columbia University P.O.Box 4042 Grand Central Station New York, NY 10163-4042 www.columbiaarmeniancenter.org S a t u r d a y , O c t o b e r 9 , 2 0 0 4 Middle East and Middle Eastern American Center (MEMEAC) The Graduate Center City University of New York 365 Fifth Avenue at 34th Street New York, NY 10016-4309 Tel: 212-817-7570 Fax: 212-817-1565 Email: [email protected] web.gc.cuny.edu/memeac Presented by: The Armenian Center at Columbia University Hosted by: The Middle East and Middle Eastern American Center (MEMEAC), The Graduate Center, CUNY Baisley Powell Elebash Recital Hall The Graduate Center City University of New York P R O G R A M Restaurant: Artisanal Honorary Chairpersons: 2 Park Avenue at 32nd Street, between Madison and Park Avenues Robert Mirak French bistro, great cheese selection, $20 lunch special. Arpena Mesrobian Restaurant: Barbès 19-21 East 36 Street, between 5th and Madison Avenues Moroccan and French cuisine. 10:15: Welcome: Michael Haratunian Restaurant: Branzini Introduction: Anny Bakalian 299 Madison Avenue, at 41st Street Mediterranean cuisine. Restaurant: Cinque Terre 10:30-12:30: The Pioneers: Early Armenian Immigrants 22 East 38th Street, between Madison and Park Avenues to the United States Northern Italian cuisine. (1) Knarik Avakian, “The Emigration of the Armenians to Restaurant: Chenai Garden the U.S.A.: Evidence from the Archives of the Armenian 129 East 27th Street (in Little India) Patriarchate of Istanbul." South Indian vegetarian. -

Iranian-American's Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination

Interpersona | An International Journal on Personal Relationships interpersona.psychopen.eu | 1981-6472 Articles Iranian-American’s Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination: Differences Between Muslim, Jewish, and Non-Religious Iranian-Americans Shari Paige* a, Elaine Hatfield a, Lu Liang a [a] University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA. Abstract Recent political events have created a political and social climate in the United States that promotes prejudice against Middle Eastern, Iranian, and Muslim peoples. In this study, we were interested in investigating two major questions: (1) How much ethnic harassment do Iranian-American men and women from various religious backgrounds (Muslim, Jewish, or no religious affiliation at all) perceive in their day-to-day interactions? (2) To what extent does the possession of stereotypical Middle Eastern, Iranian, or Muslim traits (an accent, dark skin, wearing of religious symbols, traditional garb, etc.) spark prejudice and thus the perception of ethnic harassment? Subjects were recruited from two very different sources: (1) shoppers at grocery stores in Iranian-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and (2) a survey posted on an online survey site. A total of 338 Iranian-Americans, ages 18 and older, completed an in-person or online questionnaire that included the following: a request for demographic information, an assessment of religious preferences, a survey of how “typically” Iranian-American Muslim or Iranian-American Jewish the respondents’ traits were, and the Ethnic Harassment Experiences Scale. One surprise was that, in general, our participants reported experiencing a great deal of ethnic harassment. As predicted, Iranian-American Muslim men perceived the most discrimination—far more discrimination than did American Muslim women. -

Whiteness As an Act of Belonging: White Turks Phenomenon in the Post 9/11 World

WHITENESS AS AN ACT OF BELONGING: WHITE TURKS PHENOMENON IN THE POST 9/11 WORLD ILGIN YORUKOGLU Department of Social Sciences, Human Services and Criminal Justice The City University of New York [email protected] Abstract: Turks, along with other people of the Middle East, retain a claim to being “Cau- casian”. Technically white, Turks do not fit neatly into Western racial categories especially after 9/11, and with the increasing normalization of racist discourses in Western politics, their assumed religious and geographical identities categorise “secular” Turks along with their Muslim “others” and, crucially, suggest a “non-white” status. In this context, for Turks who explicitly refuse to be presented along with “Islamists”, “whiteness” becomes an act of belonging to “the West” (instead of the East, to “the civilised world” instead of the world of terrorism). The White Turks phenomenon does not only reveal the fluidity of racial categories, it also helps question the meaning of resistance and racial identification “from below”. In dealing with their insecurities with their place in the world, White Turks fall short of leading towards a radical democratic politics. Keywords: Whiteness, White Turks, Race, Turkish Culture, Post 9/11. INTRODUCTION: WHY STUDY WHITE TURKISHNESS Until recently, sociologists and social scientists have had very little to say about Whiteness as a distinct socio-cultural racial identity, typically problematizing only non-white status. The more recent studies of whiteness in the literature on race and ethnicity have moved us beyond a focus on racialised bodies to a broader understanding of the active role played by claims to whiteness in sustaining racism. -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

The Democrats Unite Handily

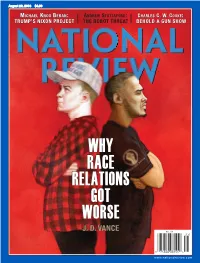

20160829_postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/9/2016 6:40 PM Page 1 August 29, 2016 $4.99 MICHAELICHAEL KNOX BERAN:: ANDREW STUTTAFORD: CHARLES C. W. COOKE:: TRUMP’S NIXON PROJECT THE ROBOT THREAT BEHOLD A GUN SHOW WHY RACE RELATIONS GOT WORSEJ.J. D.D. VANCE VANCE www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/11/2016 3:41 PM Page 1 NATIONAL REVIEW INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES THE 3rd Annual HONORING SECRETARY GEORGE P. SHULTZ FOR HIS ROLE IN DEFEATING COMMUNISM WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN POLITICAL THOUGHT MICHAEL W. GREBE THE LYNDE AND HARRY BRADLEY FOUNDATION WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN SUPPORTING LIBERTY THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2016 CITY HALL SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA For his entire life, Bill Buckley sought to preserve and buttress the foundations of our free society. To honor his achievement and inspire others, National Review Institute’s Board of Trustees has created the William F. Buckley Jr. Prizes for Leadership in Political Thought and Leadership in Supporting Liberty. We hope you will join us this year in San Francisco to support the National Review mission. For reservations and additional information contact Alexandra Zimmern, National Review Institute, at 212.849.2858 or www.nrinstitute.org/wfbprize www.nrinstitute.org National Review Institute (NRI) is the sister nonprofit educational organization of the National Review magazine. NRI is a qualified 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization. EIN#13-3649537 TOC-new_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/10/2016 2:43 PM Page 1 Contents AUGUST 29, 2016 | VOLUME LXVIII, NO. 15 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 23 Stephen D. -

Ethnicity, Culture, and Mental Health Among College Students of Middle Eastern Heritage Hasti Ashtiani Raveau Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Theses 1-1-2013 Ethnicity, Culture, And Mental Health Among College Students Of Middle Eastern Heritage Hasti Ashtiani Raveau Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Raveau, Hasti Ashtiani, "Ethnicity, Culture, And Mental Health Among College Students Of Middle Eastern Heritage" (2013). Wayne State University Theses. Paper 312. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. ETHNICITY, CULTURE, AND MENTAL HEALTH AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS OF MIDDLE EASTERN HERITAGE by HASTI ASHTIANI RAVEAU THESIS Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS 2013 MAJOR: PSYCHOLOGY (Clinical) Approved by: Rita J. Casey, Ph.D. ______________________________ Advisor Date COPYRIGHT BY HASTI ASHTIANI RAVEAU 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge several people who have helped make this project possible. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Rita Casey for her continuous support and guidance. She has been an excellent role model, and her mentorship throughout the entire process has been instrumental. I would also like to thank my committee member: Dr. Emily Grekin and Dr. Jeffrey Kuentzel for their encouragement, support, and feedback. In addition, I would like to recognize all the help I received on this project from the undergraduate research assistants, Aya Muath, Shelley Quandt, Eric Gerbe, Katherine Neill, Karishma Kasad, and Elianna Lozoya. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

European and Middle-Eastern Americans POSC 592.01/Ethnic Studies 592.01 Spring 2012 Joel Fetzer MR 2:00-3:50 P.M. RAC 157 AC

European and Middle-Eastern Americans POSC 592.01/Ethnic Studies 592.01 Spring 2012 Joel Fetzer MR 2:00-3:50 p.m. RAC 157 AC 215 506-6250 Office Hours: MWR 4:00-5:00 [email protected] and by appointment http://seaver.pepperdine.edu/academics/ faculty/member.htm?facid=joel_fetzer Course Description: This course examines the history, society, politics, and cultural production of some of the major European- and Middle-Eastern-origin ethnic groups in the United States: the English, Irish, Dutch, French, Germans, Scandinavians, Italians, Russians, Poles, Jews, Arabs, and Armenians. Major topics include immigration history, ethnic politics and identity, ethnic prejudice and conflict, white supremacism, and institutions of cultural maintenance. Counts as a core course for the Ethnic Studies minor and an upper-division American politics course for the Political Science major. Prerequisites: None. Student Learning Outcomes: After successfully completing this course, a student should be able to: - explain the historical patterns of migration to the United States from Europe and the Middle East; - identify the cultural and political differences and similarities among the principal European and Middle-Eastern nationalities in the United States; and - detail how the social, political, and economic institutions in this country benefit certain ethnic groups to a greater or lesser extent. Requirements: Successful completion of this course will require attending class regularly and participating actively in class discussions (10% of grade), reporting orally on an interview with a European or Middle-Eastern American (10% of grade, pass/fail converts to rest of term grade if pass); reading the assigned texts, performing creditably on the midterm (25% of grade) and final (30% of grade) examinations, and completing a 10-12 page research paper (25% of grade).