Discussion Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fdi European Cities and Regions of the Future 2020-21

CONTENTS Published by The Financial Times Ltd, Bracken House, 1 Friday Street, London EC4M 9BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7873 3000. Editorial fax: +44 (0)1858 461873. Staff members can be contacted by dialing +44 (0)20 7775 followed by their extension number Editor-in-Chief Courtney Fingar 6365 [email protected] Deputy Editor Jacopo Dettoni 4339 [email protected] Global Markets Editor Sebastian Shehadi 3186 [email protected] Global Investment Reporter Alex Irwin-Hunt 6437 [email protected] Production Manager Richard Gardham 6367 [email protected] Deputy Production Editor Andrew Petrie 6230 [email protected] Executive Editor Brian Caplen 6364 [email protected] Art Director Paramjit Virdee 6535 [email protected] Advertisement Executive Sophie Horton 4830 [email protected] Global Business Director Adrian Northey 6333 [email protected] Associate Publisher Charlotte Lloyd +34 (0)682736571 [email protected] Associate Publisher Luke McGreevy +971 (0)4 391 4398 [email protected] Publishing Director Angus Cushley 6354 [email protected] B2B Marketing Manager Lauren Drew 4462 [email protected] Senior Marketing Executive Jay Seenundun 6896 [email protected] Magazine customer services CDS Global, Tower House, Lathkill Street, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough, Leics, UK. LE16 9EF [email protected] tel: 0845 456 1516 (customer services) 01858 438417 (overseas), fax: +44 (0)1858 461 873 The Financial Times adheres to a self-regulation regime under the FT Editorial Code of Practice: www.ft.com/editorialcode INTRODUCTION Printed by Walstead Group in the UK In spite of the uncertainty caused by Brexit, London retains its position as fDi’s European City of the Future Registered Number: 227590 (England and Wales) ISSN: 1476-301X © Financial Times Ltd 2020. -

Cohesion And/Or Growth? Regional Dimensions of Convergence and Growth in Hungary

STUDIES Andrea Elekes Cohesion and/or Growth? Regional Dimensions of Convergence and Growth in Hungary SUMMARY: Convergence and territorially balanced economic growth require faster economic growth in weaker regions. It is dif- ficult to decide what measures would strengthen the growth capacity of regions most. Following a brief review of growth the- ories and the growth and catch-up performance of the Hungarian economy, the study focuses on the differences in develop- ment across regions in Hungary. Both the analysis of available statistical data and the calculations in connection with the catch-up rate show that the Hungarian regional development is strongly differentiated, and the so-called centre–periphery relationship can clearly be identified. Growth factors (e.g. human capital and R&D investment, innovation) should be enhanced simultaneously. Cohesion policy can complement and support growth objectives in many areas. Moreover, through the coordination of the innovation and cohesion policies even the trade-off problem between efficiency and convergence may be reduced. KEYWORDS: regional convergence, growth, cohesion, crisis JEL-CODES: F43, R11, R12 Convergence and territorially balanced eco- will be discussed next. The third part focuses nomic growth require a faster increase in on the differences in domestic regional devel- income, employment and economy in weaker opment, primarily through an analysis of the regions than in stronger ones. However, it is statistical data regarding the factors identified rather difficult to decide what measures would in the theoretical section. strengthen the growth capacity of regions Following the mapping of domestic regional Cmost. development, the question arises what role This study is, therefore, essentially searching cohesion policy may play in convergence and in for answers for the following questions. -

Regional Disparities of GDP in Hungary, 2007

23/2009 Compiled by: Hungarian Central Statistical Office www.ksh.hu Issue 23 of Volume III 25 September 2009 Regional disparities of GDP in Hungary, 2007 in Western Transdanubia and Central Transdanubia, respectively. The Contents order of the three regions was unaltered according to regional GDP cal- culations dating back for 14 years. The remaining four regions (lagging 1 Gross domestic product per capita behind the national average by 32%–37%) reached nearly the same level 2 Gross value added each: Southern Transdanubia kept its fourth position for ten years, pre- 3 International comparison ceding Southern Great Plain. Northern Hungary overtook Northern Great Plain in 2004, which order remained unchanged. Charts 4 The per capita indicator changed at different rates region by region in 7 Tables the previous year: the growth was the highest in Central Transdanubia (10%) and the lowest in Western Transdanubia (5%). Differences between regions were similar in the period under review as in 2006. The GDP per capita in the most developed region of the country (Central According to data for 2007 on the regional distribution of gross domes- Hungary) was invariably 2.6 times higher than in the one ranked last tic product regional disparities did not change significantly compared to (Northern Great Plain). Leaving out of consideration the figure for the previous year. Hungary’s gross domestic product measured at cur- Central Hungary – that includes the capital city – Western Transdanubia rent purchase prices amounted to HUF 25,479 billion in 2007, nearly the has the highest GDP per capita, which differs from the indicator value of half (47%) of which was produced in Central Hungary. -

Labour Market Comparison

Effective Cross-border Co-operation for Development of Employment Growths in Arad and Békés County – Labour Market Comparison 2019 ROHU 406: CROSSGROWING Effective cross-border co-operation for development of employment growths in Arad and Békés County Békés County Foundation for Enterprise Development The content of this study does not necessarily represent the official position of the European Union. The project was implemented under the Interreg V-A Romania-Hungary Programme, and is financed by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund, Romania and Hungary. Copyright © 2019 BMVA. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................... 5 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 14 3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH ........................................... 19 3.1. The labour market as an area of intervention ....................................................... 19 3.1.1. Production factors, supply and demand in the labour market ....................... 21 3.1.2. Unemployment and labour shortages ............................................................ 25 3.1.3. Employment and employment policy .............................................................. 31 3.2. System of cross-border cooperation ..................................................................... 37 3.2.1. Theories and principles of cross-border cooperation ................................... -

EU Mapping of Child Protection Systems Lot 16

Report of Various Sizes (FRANET) EU mapping of child protection systems Lot 16 – Hungary 2 April 2014 Contents I. Legislative framework and policy developments ................................................... 2 II. Structures and Actors ...................................................................................... 41 III. Capacities ...................................................................................................... 77 IV. Care ........................................................................................................... 91 V. Accountability ............................................................................................... 118 References ........................................................................................................ 166 Annex – Terms and definitions ............................................................................. 183 1 I. Legislative framework and policy developments 1. Overview of the normative framework of the national child protection system. 1. Normative framework: The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN CRC) was ratified in 1991 in Hungary1. The new Child Protection Act in accordance with the CRC came into force in November of 19972. Its main goal is to promote the best interests, the protection and wellbeing of children. The normative framework ensures the well- being and the protection of children from violence, exploitation, abuse, neglect, trafficking, child labour, and child separation. The children’s’ rights approach -

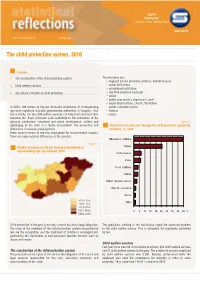

The Child Protection System, 2010

12/2011 Produced by: Hungarian Central Statistical Office www.ksh.hu Issue 6 of Volume 12 29 July 2011 The child protection system, 2010 Contents 1 The construction of the child protective system The members are: – hygienic service providers (doctors, district nurses) 1 Child welfare services – social institutions – educational institutions 2 The notary’s function in child protection – day time provision (nursery) – police – public prosecutor's department, court – social organisations, church, foundation In 2010, 108 minors at risk per thousand inhabitants of corresponding – patron custodial service age were registered at public guardianship authorities in Hungary. They – citizens live in family, but the child welfare services can help them and ease their – notary everyday life. Basic provision shall contribute to the promotion of the physical, intellectual, emotional and moral development, welfare and Figure 2 upbringing of the child in a family environment, the prevention and Distribution of calls sent through the child protective system by elimination of existing endangerment. members, %, 2010 Every second minors at risk was endangered for environmental reasons. There are huge regional differences in the country: Educational institution Figure 1 Number of minors at risk per thousand inhabitants of Notary corresponding age, by counties, 2010 District nurses Police Social institution Citizen Patron custodial serv ice Day time prov ision Doctor 42.0– 53.8 Other 53.9– 81.2 81.3 – 113.2 113.3 – 144.9 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 % 145.0 – 248.2 Child protection in Hungary is not only a moral but also a legal obligation. The specialists working in the institutions signal the observed problem The tasks of the members of the child protection system prescribed by to the child welfare service. -

Country Compendium

Country Compendium A companion to the English Style Guide July 2021 Translation © European Union, 2011, 2021. The reproduction and reuse of this document is authorised, provided the sources and authors are acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The right holders and authors shall not be liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................1 Austria ......................................................................................3 Geography ................................................................................................................... 3 Judicial bodies ............................................................................................................ 4 Legal instruments ........................................................................................................ 5 Government bodies and administrative divisions ....................................................... 6 Law gazettes, official gazettes and official journals ................................................... 6 Belgium .....................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Judicial bodies .......................................................................................................... 10 Legal instruments ..................................................................................................... -

Northern Hungary REGIONAL REPORT on IS 31TH JULY 2010

Northern Hungary REGIONAL REPORT ON IS 31TH JULY 2010 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DLA – Regional Report on IS – Northern Hungary 1 Regional Report on IS - Northern Hungary ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DLA – Regional Report on IS – Northern Hungary 2 Regional Report on IS - Northern Hungary CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Socio-economic data ....................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Regional SWOT Analysis .............................................................................................................. 13 2. The Information Society in Region: information and data .................................................................... 15 2.1 Diffusion of the main instruments .............................................................................................. 15 2.1.1 Use of the PC......................................................................................................................... -

A Kézirat Elkészítésére Vonatkozó Előírások

Integrated Regional Development /Theoretical Textbook/ Integrated Regional Development /Theoretical Textbook/ Written by: Béla Baranyi University of Debrecen Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences and Environmental Management Edited by: Béla Baranyi Reviewed by: Gábor Zongor Hungarian Association of Settlement Local Governments Translated by: Krisztina Kormosné Koch University of Debrecen Faculty of Applied University of Pannonia Economics and Rural Faculty of Georgikon Development University of Debrecen, Centre for Agricultural and Applied Economic Sciences • Debrecen, 2013 © Béla Baranyi, 2013 2 Manuscript finished: June 15, 2013 ISBN ISBN 978-615-5183-85-0 UNIVERSITY OF DEBRECEN CENTRE FOR AGRICULTURAL AND APPLIED ECONOMIC SCIENCES This publication is supported by the project numbered TÁMOP-4.1.2.A/1-11/1-2011-0029. 3 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 1. The Objective, Content and Methodology of Regional Development ............................. 8 1.1. Integrated Regional Development ................................................................................... 8 1.2. Regional Sciences ......................................................................................................... 10 1.3. Integrated Regional Development and Related Definitions .......................................... 15 1.4. Control Questions ......................................................................................................... -

Verejná Politika Ako Nástroj Znižovaní Regionálnych Disparít Public Policy As a Tool to Decrease Regional Disparities

Verejná politika ako nástroj znižovaní regionálnych disparít Public Policy as a Tool to Decrease Regional Disparities Anna Čepelová, Milan Douša Abstract Scope of this article is content analysis of regional disparities in Hungary in regions at NUTS 2 and NUTS 3 level with main focus on social disparities, as well as evaluation of possible solutions of regional disparities by national regional policies and by Cohesion Policy of the European Union in Programming Period 2014-2020. General part of the article clarifies functioning of regional structure of Hungary and regional disparities as recognized by Cohesion Policy. Second part of this article is dedicated to differences among regions at NUTS 2 and NUTS 3 levels in Hungary based on analysis of unemployment rate and in consideration of their development. Presented contribution is part of solution of Project VEGA č.1/00302/18 „Smart cities as a possibility for implementation of the concept of sustainable urban development in the Slovak Republic“. Keywords: european regional cooperation, nuts nomenclature, cohesion policy, regional policy, regional disparities Introduction As well as there are economic, social and territorial differences between the Member States of the European Union, there are also differences in each Member State at regional level. These differences are also apparent in Hungary and Slovakia, as both countries have regions whose overall socio-economic level does not correspond to the national average. These differences are known as regional disparities which are defined as "unjustified regional differences in level of economic, social and ecological development of the regions". In case of Hungary, the largest disparities are apparent among the region with the capital city and eastern peripheral regions, and among the regions bordering with southern and eastern regions of Slovakia. -

Regional Distribution of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 2010 (Preliminary Data) May 2012

© Hungarian Central Statistical Offi ce Regional distribution of gross domestic product (GDP), 2010 (preliminary data) May 2012 Contents Regional distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 (preliminary data) ....................2 Tables ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Table 1 Regional distribution of gross domestic product (GDP), 2007–2010 ..........................6 Table 2 Per capita gross domestic product (GDP), 2007–2010 .............................................. 8 Table 3 Order of counties and regions on the basis of GDP per capita, 2007–2010 ............... 9 Table 4 Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in PPS, 2007–2010 ................................ 10 Table 5 Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in PPS, EU-27=100, 2007–2010 .............11 Table 6 Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) as a percentage of national average, 2007–2010 ................................................................................. 12 Table 7 Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) as a percentage of counties’ average, 2007–2010 ............................................................................... 13 Table 8 Classifi cation of per capita gross domestic product of counties according to difference from counties’ average, 2009–2010 ..................................14 Table 9 Gross value added by industries, at current prices, 2007 .........................................15 Table 10 Gross value added by industries, -

Regional Distribution of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2011 (Preliminary Data) June 2013

© Hungarian Central Statistical Office Regional distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011 (preliminary data) June 2013 Contents Regional distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011 ................................................. 2 Tables ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Regional distribution of gross domestic product, 2009–2011 ............................................... 6 2. Per capita gross domestic product (GDP), 2009–2011 ........................................................ 8 3. Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in PPS, 2009–2011 ............................................ 9 4. Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) as a percentage of national and counties’ average, 2009–2011 ................................................................ 10 5. Classification of per capita GDP of counties by difference from counties’ average, 2010–2011 ..........................................................................................11 6. Gross value added by industries at current prices, 2010 ................................................... 12 7. Gross value added by industries at current prices, 2011 .................................................... 13 Methodological notes................................................................................................................ 14 Contact details www.ksh.hu Regional distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011 (preliminary