D3.1 National Report Hungary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Have EU Countries Done to Support Low-Wage Workers in an Era of Downward Wage Pressures?

IZA DP No. 9390 Stemming the Tide: What Have EU Countries Done to Support Low-Wage Workers in an Era of Downward Wage Pressures? Sarah Marchal Ive Marx September 2015 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Stemming the Tide: What Have EU Countries Done to Support Low-Wage Workers in an Era of Downward Wage Pressures? Sarah Marchal Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy, University of Antwerp Ive Marx Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy, University of Antwerp and IZA Discussion Paper No. 9390 September 2015 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. -

Fdi European Cities and Regions of the Future 2020-21

CONTENTS Published by The Financial Times Ltd, Bracken House, 1 Friday Street, London EC4M 9BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7873 3000. Editorial fax: +44 (0)1858 461873. Staff members can be contacted by dialing +44 (0)20 7775 followed by their extension number Editor-in-Chief Courtney Fingar 6365 [email protected] Deputy Editor Jacopo Dettoni 4339 [email protected] Global Markets Editor Sebastian Shehadi 3186 [email protected] Global Investment Reporter Alex Irwin-Hunt 6437 [email protected] Production Manager Richard Gardham 6367 [email protected] Deputy Production Editor Andrew Petrie 6230 [email protected] Executive Editor Brian Caplen 6364 [email protected] Art Director Paramjit Virdee 6535 [email protected] Advertisement Executive Sophie Horton 4830 [email protected] Global Business Director Adrian Northey 6333 [email protected] Associate Publisher Charlotte Lloyd +34 (0)682736571 [email protected] Associate Publisher Luke McGreevy +971 (0)4 391 4398 [email protected] Publishing Director Angus Cushley 6354 [email protected] B2B Marketing Manager Lauren Drew 4462 [email protected] Senior Marketing Executive Jay Seenundun 6896 [email protected] Magazine customer services CDS Global, Tower House, Lathkill Street, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough, Leics, UK. LE16 9EF [email protected] tel: 0845 456 1516 (customer services) 01858 438417 (overseas), fax: +44 (0)1858 461 873 The Financial Times adheres to a self-regulation regime under the FT Editorial Code of Practice: www.ft.com/editorialcode INTRODUCTION Printed by Walstead Group in the UK In spite of the uncertainty caused by Brexit, London retains its position as fDi’s European City of the Future Registered Number: 227590 (England and Wales) ISSN: 1476-301X © Financial Times Ltd 2020. -

Pancreatic Cancer: Multicenter Prospective Data Collection and Analysis by the Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SZTE Publicatio Repozitórium - SZTE - Repository of Publications original paper Available from: http://www.jgld.ro/wp/archive/y2016/n2/a15 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.252.pcr Pancreatic Cancer: Multicenter Prospective Data Collection and Analysis by the Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group Gábor Lakatos1, Anita Balázs2, Balázs Kui2, Szilárd Gódi3, Ákos Szücs4, Andrea Szentesi2, Zsolt Szentkereszty5, Richárd Szmola6, Dezső Kelemen7, Róbert Papp7, Áron Vincze3, József Czimmer3, Gabriella Pár3, Judit Bajor3, Imre Szabó3, Ferenc Izbéki8, Adrienn Halász8, László Leindler9, Gyula Farkas Jr.9, Tamás Takács2, László Czakó2, Zoltán Szepes2, Péter Hegyi2,10, 11*, Zsuzsanna Kahán12,* 1) Dept. Oncology, St. Istvan Abstract and St. Laszlo Hospital and Out- Patient Department, Budapest; Background & Aims: Pancreatic cancer is a devastating disease with poor prognosis. There is very limited 2) 1st Dept. Medicine, University information available regarding the epidemiology and treatment strategies of pancreatic cancer in Central of Szeged; 3) 1st Dept. Medicine, Europe. The purpose of the study was to prospectively collect and analyze data of pancreatic cancer in the University of Pécs; 4) 1st Dept. Hungarian population. Surgery, Semmelweis University, Methods: The Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group (HPSG) organized prospective, uniform data collection. Budapest; 5) Institute of Surgery, Altogether 354 patients were enrolled from 14 Hungarian centers. Clinical Center, University of Results: Chronic pancreatitis was present in 3.7% of the cases, while 33.7% of the patients had diabetes. Debrecen; 6) Dept. Interventional Family history for pancreatic cancer was positive in 4.8%. -

Cohesion And/Or Growth? Regional Dimensions of Convergence and Growth in Hungary

STUDIES Andrea Elekes Cohesion and/or Growth? Regional Dimensions of Convergence and Growth in Hungary SUMMARY: Convergence and territorially balanced economic growth require faster economic growth in weaker regions. It is dif- ficult to decide what measures would strengthen the growth capacity of regions most. Following a brief review of growth the- ories and the growth and catch-up performance of the Hungarian economy, the study focuses on the differences in develop- ment across regions in Hungary. Both the analysis of available statistical data and the calculations in connection with the catch-up rate show that the Hungarian regional development is strongly differentiated, and the so-called centre–periphery relationship can clearly be identified. Growth factors (e.g. human capital and R&D investment, innovation) should be enhanced simultaneously. Cohesion policy can complement and support growth objectives in many areas. Moreover, through the coordination of the innovation and cohesion policies even the trade-off problem between efficiency and convergence may be reduced. KEYWORDS: regional convergence, growth, cohesion, crisis JEL-CODES: F43, R11, R12 Convergence and territorially balanced eco- will be discussed next. The third part focuses nomic growth require a faster increase in on the differences in domestic regional devel- income, employment and economy in weaker opment, primarily through an analysis of the regions than in stronger ones. However, it is statistical data regarding the factors identified rather difficult to decide what measures would in the theoretical section. strengthen the growth capacity of regions Following the mapping of domestic regional Cmost. development, the question arises what role This study is, therefore, essentially searching cohesion policy may play in convergence and in for answers for the following questions. -

Regional Disparities of GDP in Hungary, 2007

23/2009 Compiled by: Hungarian Central Statistical Office www.ksh.hu Issue 23 of Volume III 25 September 2009 Regional disparities of GDP in Hungary, 2007 in Western Transdanubia and Central Transdanubia, respectively. The Contents order of the three regions was unaltered according to regional GDP cal- culations dating back for 14 years. The remaining four regions (lagging 1 Gross domestic product per capita behind the national average by 32%–37%) reached nearly the same level 2 Gross value added each: Southern Transdanubia kept its fourth position for ten years, pre- 3 International comparison ceding Southern Great Plain. Northern Hungary overtook Northern Great Plain in 2004, which order remained unchanged. Charts 4 The per capita indicator changed at different rates region by region in 7 Tables the previous year: the growth was the highest in Central Transdanubia (10%) and the lowest in Western Transdanubia (5%). Differences between regions were similar in the period under review as in 2006. The GDP per capita in the most developed region of the country (Central According to data for 2007 on the regional distribution of gross domes- Hungary) was invariably 2.6 times higher than in the one ranked last tic product regional disparities did not change significantly compared to (Northern Great Plain). Leaving out of consideration the figure for the previous year. Hungary’s gross domestic product measured at cur- Central Hungary – that includes the capital city – Western Transdanubia rent purchase prices amounted to HUF 25,479 billion in 2007, nearly the has the highest GDP per capita, which differs from the indicator value of half (47%) of which was produced in Central Hungary. -

Budapest Vs. the Countryside

american chamber of commerce in hungary VOICEVol III. Issue 11, march 2013 BuDa pest vS. thE cOuNtRyside And thE demogRaphIc time bomb MORE INSIDE: Education that serves society Innovation – you can’t do it alone 3 contents 4 introduction 15-19 COVEr STORY 30 AmchAm nEwS Dear Members and Friends… capital vs. countryside New board, new president 5 PEoPLE 31 AmchAm nEwS the glass half full 20-21 COVEr STORY hungarian tax system: 6 PEoPLE the demographic time bomb Swedish taxes with traveling at the speed Ethiopian wages of google 22-23 Lifestyle AmchAm nEwS 7 PEople andrás török’s Budapest 32 adding value, boosting Innovation – you can’t confidence do it alone 24-25 focuS 8 AnALYSiS Education that serves society 33 chAmbEr cornEr Will the largest grow larger? providing a reasoned voice 26 AmchAm nEwS 91-11 AnALYSiS Business news roundup hungary ‘not an island’ 36-37 AmchAm nEwS New members on board 12-13 AnALisys AMCHAm NewS hungary moves deeper 27 38-41 AmchAm nEwS into recession Shifting toward growth photo coverage 14 AnALYSiS 28-29 AmchAm NewS BSE saw a drastic drop in 42 AmchAm nEwS turnover in 2012 a cooperative approach to tax cEO’s note Voice is published on behalf of the American Chamber of Commerce by Absolut Media Zrt., Madách Trade Center, 1075 Budapest, Madách Imre út 13-14., Building A, 8th floor Editor-in-chief: ROBIN MARSHALL ([email protected]) • Contributors: GABRIELLA LOVAS, ROBIN MARSHALL, ANDRÁS TÖRÖK Photography: András HAJnal, LÁZár TodoroFF • Design: ABSOLUT DESIGN STÚDIÓ ([email protected]) • Art director: Tamás TárCZY • CEO: TAMÁS BOTKA Advertising: ABSOLUT MEDIA Zrt. -

Labour Market Comparison

Effective Cross-border Co-operation for Development of Employment Growths in Arad and Békés County – Labour Market Comparison 2019 ROHU 406: CROSSGROWING Effective cross-border co-operation for development of employment growths in Arad and Békés County Békés County Foundation for Enterprise Development The content of this study does not necessarily represent the official position of the European Union. The project was implemented under the Interreg V-A Romania-Hungary Programme, and is financed by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund, Romania and Hungary. Copyright © 2019 BMVA. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................... 5 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 14 3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH ........................................... 19 3.1. The labour market as an area of intervention ....................................................... 19 3.1.1. Production factors, supply and demand in the labour market ....................... 21 3.1.2. Unemployment and labour shortages ............................................................ 25 3.1.3. Employment and employment policy .............................................................. 31 3.2. System of cross-border cooperation ..................................................................... 37 3.2.1. Theories and principles of cross-border cooperation ................................... -

EU Mapping of Child Protection Systems Lot 16

Report of Various Sizes (FRANET) EU mapping of child protection systems Lot 16 – Hungary 2 April 2014 Contents I. Legislative framework and policy developments ................................................... 2 II. Structures and Actors ...................................................................................... 41 III. Capacities ...................................................................................................... 77 IV. Care ........................................................................................................... 91 V. Accountability ............................................................................................... 118 References ........................................................................................................ 166 Annex – Terms and definitions ............................................................................. 183 1 I. Legislative framework and policy developments 1. Overview of the normative framework of the national child protection system. 1. Normative framework: The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN CRC) was ratified in 1991 in Hungary1. The new Child Protection Act in accordance with the CRC came into force in November of 19972. Its main goal is to promote the best interests, the protection and wellbeing of children. The normative framework ensures the well- being and the protection of children from violence, exploitation, abuse, neglect, trafficking, child labour, and child separation. The children’s’ rights approach -

The Case of the 2011 Hungarian Higher Education Policy Reforms

MULTIPLE DIMENSIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION POLICY: IS THERE A COMMON GOAL? The Case of the 2011 Hungarian Higher Education Policy Reforms by Aniko Toth Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science (2-year) CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Professor Matteo Fumagalli Budapest, Hungary (2014) ABSTRACT Higher education has been shaped by the effects of globalization, internationalization, and massification. As a result, there are various stakeholders in higher education and there are shifting relations among their interests, which can generate different takes on what direction higher education should head towards. The thesis focuses on the case of the 2011 Hungarian higher education reforms applying a structural approach to reveal the different dimensions the reforms are linked to and to assess the effectiveness of the policies. The macro (global and European patterns of higher education policy), meso (social, political, legal, and economic aspects of Hungarian higher education) and micro levels (students and higher education in Hungary) are revisited keeping the reforms the recurring reference point. The main proposition states that there is a mismatch between the Hungarian policies and the European and global patterns of higher education policy suggesting the existence of a policy-gap that remains unresolved by the reforms. The thesis reveals the gap, and based on the combined assessment of the three-levels of the analysis, it suggests recommendations on the advancement of the policy. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Professor Matteo Fumagalli for his support, guidance, and important suggestions on my work. -

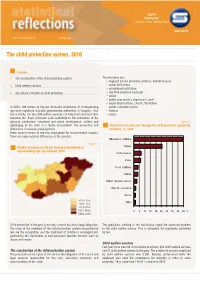

The Child Protection System, 2010

12/2011 Produced by: Hungarian Central Statistical Office www.ksh.hu Issue 6 of Volume 12 29 July 2011 The child protection system, 2010 Contents 1 The construction of the child protective system The members are: – hygienic service providers (doctors, district nurses) 1 Child welfare services – social institutions – educational institutions 2 The notary’s function in child protection – day time provision (nursery) – police – public prosecutor's department, court – social organisations, church, foundation In 2010, 108 minors at risk per thousand inhabitants of corresponding – patron custodial service age were registered at public guardianship authorities in Hungary. They – citizens live in family, but the child welfare services can help them and ease their – notary everyday life. Basic provision shall contribute to the promotion of the physical, intellectual, emotional and moral development, welfare and Figure 2 upbringing of the child in a family environment, the prevention and Distribution of calls sent through the child protective system by elimination of existing endangerment. members, %, 2010 Every second minors at risk was endangered for environmental reasons. There are huge regional differences in the country: Educational institution Figure 1 Number of minors at risk per thousand inhabitants of Notary corresponding age, by counties, 2010 District nurses Police Social institution Citizen Patron custodial serv ice Day time prov ision Doctor 42.0– 53.8 Other 53.9– 81.2 81.3 – 113.2 113.3 – 144.9 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 % 145.0 – 248.2 Child protection in Hungary is not only a moral but also a legal obligation. The specialists working in the institutions signal the observed problem The tasks of the members of the child protection system prescribed by to the child welfare service. -

The Road to Flexibility? Lessons from the New

THE ROAD TO FLEXIBILITY? LESSONS FROM THE NEW PROEF 1e HUNGARIAN LABOUR CODE T"-/3 G678":/#'* and N'%;8&<< H=3** Abstract As a result of a general revision, a new Labour Code entered into force on 1 July 2012 in Hungary. One of the determining objectives of the recent labour law reform was ‘ exibilisation’, and ensuring that regulation by labour law should be kept to a minimum. e new rules increased the contractual freedom of parties, and particularly the role of collective agreements in the regulation of employment relationships. While maintaining the basic structure of Hungarian labour law, the new Labour Code introduced conceptual changes in several key areas, such as the termination of employment relationships, liability for damages and collective rights. ese changes were justi ed by the government on the grounds that the current labour law regulation was too rigid and that did not re ect the private law foundations of this eld of law su ciently. e article puts this statement under critical review and gives an overview of the most important elements of the labour law reform. In particular, a er a short introduction we will examine what changes the new Labour Code introduced in the hierarchy of legal sources, and what attempts were made to extend the scope of the Labour Code to other forms of employment. Further, we will analyse to what extent the changes introduced by the new Labour Code modi ed the balance between the interests of employees and employers. Finally, we will also give an overview of the relationship between the new Labour Code and EU labour law. -

Country Compendium

Country Compendium A companion to the English Style Guide July 2021 Translation © European Union, 2011, 2021. The reproduction and reuse of this document is authorised, provided the sources and authors are acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The right holders and authors shall not be liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................1 Austria ......................................................................................3 Geography ................................................................................................................... 3 Judicial bodies ............................................................................................................ 4 Legal instruments ........................................................................................................ 5 Government bodies and administrative divisions ....................................................... 6 Law gazettes, official gazettes and official journals ................................................... 6 Belgium .....................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Judicial bodies .......................................................................................................... 10 Legal instruments .....................................................................................................