Topic Three: Community Involvement in the Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support I. REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Davao Region still needs to improve its infrastructure facilities and services. While the Davao International Airport has been recently completed, road infrastructure, seaport, and telecommunication facilities need to be upgraded. Flood control and similar structures are needed in flood prone areas while power and water supply facilities are still lacking in the region’s remote and underserved areas. While the region is pushing for increased production of staple crops, irrigation support facilities in major agricultural production areas are still inadequate. Off-site infrastructure in designated tourism and agri-industrial areas are likewise needed to encourage investment and spur economic activities. Accessibility and Mobility through Transport There is a need for the construction of new roads and improvement of the existing road network to provide better access and linkage within and outside the Region as an alternate to existing arterial and local roads. The lack of good roads in the interior parts of the municipalities and provinces connecting to major arterial roads constrains the growth of agriculture and industry in the Region; it also limits the operations of transport services due to high maintenance cost and longer turnaround time. Traffic congestion is likewise becoming a problem in highly urbanized and urbanizing areas like Davao City and Tagum City. While the Region is physically connected with the adjoining regions in Mindanao, poor road condition in some major highways also hampers inter-regional economic activities. The expansion of agricultural activities in the resettlement and key production areas necessitates the opening and construction of alternative routes and farm-to-market roads. -

Dole Regional Office Xi Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries Monitoring Form

DOLE-GIP_Form C DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE XI GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES MONITORING FORM NATURE OF DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS NAME EDUCATIONAL OFFICE/PLACE OF ADDRESS AGE GENDER DOCUMENTS SUBMITTED WORK/ (Last Name, First Name, MI) ATTAINMENT ASSIGNMENT ASSIGNMENT (e.g. Contract completed or START DATE END DATE preterminated *APPLICATION FORM BS IN HOTEL AND 678, MANGUSTAN ST., MADAUM, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 1 ALIVIO, FEMAE JEAN B. 23 F RESTAURANT W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going TAGUM CITY CERTIFICATE *TOR *ACCIDENT MANAGEMENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM PRK. 19-B, KATIPUNAN, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 2 BALIENTES, MARIA KATHLEEN G. 20 F BS IN ACCOUNTING W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going MADAUM, TAGUM CITY CERTIFICATE *SPR *ACCIDENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM BS IN HOTEL AND PRK. 5-A, APOKON, TAGUM *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 3 CANTILA, GEBBIE M. 20 F RESTAURANT W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/19/2018 11/17/2018 On going CITY, DAVAO DEL NORTE CERTIFICATE *DIPLOMA MANAGEMENT *ACCIDENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM PRK. 1, TANGLAW, BE DUJALI, BS IN BUSINESS *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 4 ESTAÑOL, ANNA MAE D. 21 F W/IN BE DUJALI CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going DAVAO DEL NORTE ADMINISTRATION CERTIFICATE *DIPLOMA/TOR *BRGY. CERT *APPLICATION FORM BACHELOR OF PRK. 4, NARRA, GABUYAN, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 5 LOPEZ, MARYJAN P. 23 SECONDARY W/IN KAPALONG CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going KAPALONG, DAVAO DEL NORTE CERTIFICATE *MARRIAGE CERT., EDUCATION *TOR *CERT OF INDIGENCY M *APPLICATION FORM PRK. -

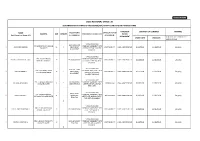

TIER1 Agency: BUREAU of JAIL MANAGEMENT and PENOLOGY

TIER1 Agency: BUREAU OF JAIL MANAGEMENT AND PENOLOGY (BJMP) XI INVESTMENT BRIEF SPATIAL COVERAGE RDP RESULTS PROGRAMS/PROJECTS/ TARGETS (IN SOURCE OF UACS PROGRAM/PROJECT MATRIX (RM) REMARKS ACTIVITIES CONGRESSIONAL PHP'000) FUNDS DESCRIPTION PROVINCE ADDRESSED DISTRICT 2019 MFO: SAFEKEEPING & DEVELOPMENT OF INMATES (i) Security Management of Inmates: Provision of Escorting Services, Conduct of Regionwide Inspections, Davao City/Del Travel Expenses 1st 713.77 GAA personnel inventories & Sur local travels for official businesses: Military Supplies Regionwide 181.50 GAA Fuel, Oil, Lubricant Regionwide 2,178.00 GAA Expenses (ii) Improvement and Maintenance of Jail Water Expenses Regionwide 7,920.00 GAA Facilities & Equipment: Electricity Expenses Regionwide 9,900.00 GAA Repair/Improvement - Davao City/Del 1st _ GAA Davao City Jail Sur Repair/Improvement - Davao City/Del 1st _ GAA Davao City Female Jail Sur Repair/Improvement - Davao City/Del 1st _ GAA Davao City Jail-Annex Sur Repair/Improvement - Digos City District Del Sur 1st _ GAA Female Jail 6-1 INVESTMENT BRIEF SPATIAL COVERAGE RDP RESULTS PROGRAMS/PROJECTS/ TARGETS (IN SOURCE OF UACS PROGRAM/PROJECT MATRIX (RM) REMARKS ACTIVITIES CONGRESSIONAL PHP'000) FUNDS DESCRIPTION PROVINCE ADDRESSED DISTRICT 2019 Repair/Improvement - Del Norte 2nd _ GAA Panabo City District Jail Repair/Improvement - Del Norte 1st _ GAA Tagum City Jail Repair/Improvement - Del Norte _ GAA IGACOS City Jail Repair/Improvement - Oriental 2nd 300.00 GAA Lupon District City Jail Repairs/ Maintenance Regionwide 260.15 -

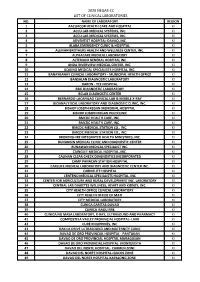

2020 Neqas-Cc List of Clinical Laboratories No

2020 NEQAS-CC LIST OF CLINICAL LABORATORIES NO. NAME OF LABORATORY REGION 1 AACUACOR HEALTH CARE AND HOSPITAL XI 2 ACCU LAB MEDICAL SYSTEMS, INC. XI 3 ACCU LAB MEDICAL SYSTEMS, INC. XI 4 ADVENTIST HOSPITAL-DAVAO, INC. XI 5 ALABA EMERGENCY CLINIC & HOSPITAL XI 6 ALEXIAN BROTHERS HEALTH AND WELLNESS CENTER, INC. XI 7 ALPHACARE MEDICAL LABORATORY XI 8 ALTERADO GENERAL HOSPITAL INC. XI 9 ANDA RIVERVIEW MEDICAL CENTER, INC. XI 10 AQUINO MEDICAL SPECIALISTS HOSPITAL, INC. XI 11 BANAYBANAY CLINICAL LABORATORY - MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE XI 12 BANSALAN DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY XI 13 BARON - YEE HOSPITAL XI 14 BBG DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY XI 15 BCLAB DIAGNOSTIC CENTER XI 16 BERNARDO-LACANILAO CLINICAL LAB & MOBILE X-RAY XI 17 BIOANALYTICAL LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC, INC. XI 18 BISHOP JOSEPH REGAN MEMORIAL HOSPITAL XI 19 BISHOP JOSEPH REGAN POLYCLINIC XI 20 BMCDC HEALTH CARE, INC. XI 21 BMCDC HEALTH CARE, INC. XI 22 BMCDC MEDICAL STATION CO., INC. XI 23 BMCDC MEDICAL STATION CO., INC. XI 24 BROKENSHIRE INTEGRATED HEALTH MINISTRIES, INC. XI 25 BUHANGIN MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER XI 26 BUNAWAN MEDICAL SPECIALIST INC. XI 27 CAINGLET MEDICAL HOSPITAL, INC. XI 28 CALINAN CLEAR CHECK DIAGNOSTICS INCORPORATED XI 29 CAMP PANACAN STATION HOSPITAL XI 30 CARELIFE MEDICAL LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER INC. XI 31 CARMELITE HOSPITAL XI 32 CENTENO MEDICAL SPECIALISTS HOSPITAL, INC XI 33 CENTER FOR AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT INC. LABORATORY XI 34 CENTRAL LAB DIABETES WELLNESS, HEART AND KIDNEY, INC. XI 35 CITY HEALTH OFFICE CLINICAL LABORATORY -

Sitecode Region Penro Cenro Barangay Municipality Name of Organization Contact Person Commodity Hectares

AREA IN SITECODE REGION PENRO CENRO BARANGAY MUNICIPALITY NAME OF ORGANIZATION CONTACT PERSON COMMODITY HECTARES Ancestral Domain Tribal Farmers Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Upper Ulip Monkayo Association Mauricio Latiban Trees, Rubber, Timber 75 Barangay Tribal Council of Elders & Leaders Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo San Jose Monkayo of San Jose (BTCEL San Jose) Romeo Capao Rubber, Timber 50 Camanlangan Tree Growers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Camanlangan New Bataan (CATREGA) Ruperto Sabay Sr. Timber 50 Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Casoon Monkayo Casoon Tree Farmers Association (CATFA) Gavino Ayco Timber 80 Dalaguete Lebanon San Vicente Montevista Watershed Farmers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Lebanon Montevista (DALESANMWFA) Martiniano Paniamogan Timber 37 XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Ngan Compostela Kapwersa Comval Agricultural Cooperative Alejandro Cacao, Timber 50 Magangit Upland Farmers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Fatima New Bataan (MAUFA) Clemente T. Nabor Timber 50 Mangayon Indigenous People and Farmers Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Mangayon Compostela Association (MIPFA) Timber 70 Maragusan Waterworks & Sanitation Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Poblacion Maragusan Cooperative (MAWASCO) Cesar Escuadro Trees, Timber 100 Mayaon Upland Small Farmers Association Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Mayaon Montevista (MUSFA) -

Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (Ra 8371) in 2019 Mindanao

“Forging partnership for rights-based development of the Indigenous Peoples” INDIGENOUS PEOPLES RIGHTS ACT (RA 8371) IN 2019 MINDANAO By: Atty. Ariel T. Montaňa June 11, 2019 #solidarityforIPdevelopment HISTORY When the Spaniards conquered the Philippines, they declared that!! All lands of the Philippines became the property of the King of Spain. (Regalian Doctrine) Impact of the legal system on the Indigenous Peoples When the Spaniards left, we continued to use their Government system; This did not recognize traditional land rights and ownership of ICCs/IPs; Without titles, Indigenous Peoples were forced to lose ownership of these lands. October 29, 1997 •Republic Act 8371 (Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997) became a law. LEGAL BASIS 1987 PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION (e.g. Article II, Section 22, Article XVI, Section 12) INTERNATIONAL LAW (e.g. UNDRIP) JURISPRUDENCE [(e.g. Cariňo vs. Insular Government (212 US 449)] IPRA SALIENT FEATURES: 1. Right to Ancestral Domain 2. Right to Self-Governance and Empowerment 3. Social Justice and Human Rights 4. Cultural Integrity 5. Creation of NCIP 6. Quasi-Judicial Power Right to Self Governance and Empowerment Section 13 – The State recognizes the inherent right of the ICCs/IPs to self-governance and self- determination and respects the integrity of their values, practices and institutions. Right to Self Governance and Empowerment Customary Laws (Section 65) Tribal Barangays Mandatory Representation in policy making bodies and in local legislative bodies Social Justice and Human Rights Equal Protection -

2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley

2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population COMPOSTELA VALLEY 687,195 COMPOSTELA 81,934 Bagongon 1,946 Gabi 3,891 Lagab 2,586 Mangayon 4,403 Mapaca 2,082 Maparat 3,445 New Alegria 3,262 Ngan 7,738 Osmeña 4,753 Panansalan 906 Poblacion 26,773 San Jose 5,114 San Miguel 7,354 Siocon 3,266 Tamia 2,621 Aurora 1,794 LAAK (SAN VICENTE) 70,856 Aguinaldo 4,151 Banbanon 1,352 Binasbas 1,127 Cebulida 1,797 Il Papa 1,189 Kaligutan 2,902 Kapatagan 4,461 Kidawa 2,050 Kilagding 2,012 Kiokmay 1,379 Langtud 2,896 Longanapan 2,334 Naga 1,249 Laac (Pob.) 7,150 San Antonio 2,426 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Amor Cruz 2,675 Ampawid 2,633 Andap 1,745 Anitap 505 Bagong Silang 1,063 Belmonte 1,212 Bullucan 1,229 Concepcion 1,114 Datu Ampunan 1,145 Datu Davao 1,031 Doña Josefa 894 El Katipunan 1,140 Imelda 1,996 Inacayan 1,077 Mabuhay 2,298 Macopa 707 Malinao 711 Mangloy 1,299 Melale 1,701 New Bethlehem 601 Panamoren 911 Sabud 1,211 Santa Emilia 1,438 Santo Niño 1,120 Sisimon 925 MABINI (DOÑA ALICIA) 36,807 Cadunan 3,988 Pindasan 5,524 Cuambog (Pob.) 6,016 Tagnanan (Mampising) 4,735 Anitapan 3,435 Cabuyuan 1,940 Del Pilar 2,054 Libodon 1,145 Golden Valley (Maraut) 5,061 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population -

Women's Role and Support for the Closed Shing Season in the Small

Women’s role and support for the closed shing season in the small-scale sheries (SSF) of Davao Gulf, Philippines Edison D Macusi ( [email protected] ) Davao Oriental State University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9714-1074 Erna S. Macusi Davao Oriental State University Charlen Mae Gaab Davao Oriental State University Anna Barboza Ghent University: Universiteit Gent Larry N. Digal School of Management, University of the Philippines Mindanao (UPmin) Research Article Keywords: Closed-shing season, Davao Gulf, Gender, Small-scale sheries (SSF), women empowerment Posted Date: August 10th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-638646/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/23 Abstract Women’s role and support for the sheries are barely acknowledged, they are stereotyped and marginalized and given limited participation in the sheries. This study aims to describe the role of women and investigate their support for the closed shing season in the small-scale sheries (SSF) of Davao Gulf, Philippines. Survey data were collected in six study sites, only surveying women respondents involved in shing and shery-related activities. Interviews were conducted from November 2019 to July 2020 with respondents from Governor Generoso, Lupon, Davao City, Sta. Maria, Malita, and Don Marcelino (N = 255). The information collected was validated through seven focus groups with a total number of participants, N = 112. Results showed that women respondents who live near the shore, were poorly educated, attended elementary level (38%), do not own any parcel of land (91%), but have access to micronance credit (64%). -

DAVAO CENTER for HEALTH DEVELOPMENT Os

Republic olthe Philippines Department of Health DAVAO CENTER FOR HEALTH DEVELOPMENT January 20, 2021 DCHD PERSON ORDER NO. 2021 - SUBJECT: CONFIRIIIATION OF DUTY OF PERSONNEL OF DAVAO ORIENTAL UNDER EMERGENCY HIRING FOR COVID.19 ON JANAURY 1.20,2021 AND AUTHORITY TO CONTINUE THE SCHEDULES OF DUTY ON JANUARY 21-31,2021. The duty of the following personnel under Emergency Hiring for COVID-19 of Davao Oriental at Temporary Treatment and Monitoring Facility on January 1-20, 2021 is hereby confirmed Official, to wit; NAME OF PERSONNEL DESIGNATION OFFICIAL PLACE OF wtN STATION(OS) DUTY 50KMS RADIUS FROM os Decenilla, Ruzel Nurse I Banaybanay Banaybanay Aguinaldo, Johannah Lou Nurse I Banaybanay Banaybanay Ballenas, Jay Data Encoder Banaybanay Banaybanay Flores Annie Data Encoder Banaybanay Banaybanay Me.ios Ryan Maintenance Banaybanay Banaybanay Oracion, Junyl Maintenance Banaybanay Banaybanay Antipuesto, Renie Maintenance Banaybanay Banaybanay Palanas, Suzanne Security Banaybanay Banaybanay Mejos Reygan Security Banaybanay Banaybanay Francisco, Russel Security Banaybanay Banaybanay Marpa Stephen Data Encoder Lupon Lupon Vitor, Eloisa Lethea Data Encoder Lupon Lupon Alabat Aldrin Maintenance Lupon Lupon Bahinting, Eric Von Maintenance Lupon Lupon Reyes John Cyro Maintenance Lupon Lupon Mapantoc, Ricardo Maintenance Lupon Lupon Baura Marie Lee Data Encoder Govgen Govgen Castrodes, Denzel Data Encoder Govgen Govgen Baer, Chan Maintenance Govgen Govgen Luchavez, Gerald Maintenance Govgen Govgen Divinagracia, Hanzel Bryan Maintenance Govgen Govgen Portrias, Albert Maintenance Govgen Govgen Notarte, Betcher Driver Govgen Govgen Abalunan, Noel Security Govgen Govgen Mantua, Jay Security Govgen Govgen Reputana, Wil-lme Data Encoder San lsidro San lsidro Manuales, Liezel Data Encoder San lsidro San lsidro L,wacat, Glenn Maintenance San lsidro San lsidro ui L.G Maintenance San lsidro San lsidro DOH Cornpound. -

Bureau of Soils and Water Management Nutrient

126°0' 126°30' CATARMAN ANCHORAGE 8°0' 8°0' Province of Compostela Valley R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U LT U R E Cateel Bay BUREAU OF SOILS AND WP AH TI EL RI PMP AI NN AE G SEEMAENT Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City Boston NUTRIENT STATUS MAP: POTASSIUM P H I L I P P I N E S E A ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE OF DAVAO ORIENTAL ° Cateel SCALE 1:370,000 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : PRS 1992 DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative D A V A O D E L N O R T E Baculin Bay Baganga 7°30' 7°30' Area estimated based on actual field survey, other information from DA-RFO's, MA's NIA Service Area, NAMRIA Land Cover (2010) and BSWM Land Use System Map. Caraga Province of Compostela Valley Caraga Bay DAVAO GULF BUNGA COVE Manay Manay Bay T Magnaga Bay I A R T S Province of N Davao del Norte A T U P I Tarragona K A P Banaybanay Mapanga Bay 7°0' 7°0' Mati Mayo Bay B a Lupon le te B a y Pujada Bay Cuabo Bay San Isidro Talisay Bay BAKSAL COVE Governor Generoso DAVAO GULF LOCATION MAP Surigao Agusan del Sur 8°0' del Sur BOROT COVE LUZON Davao 15° del Norte Compostela Pujada Bay Valley Davao DAVAO City ORIENTAL 7°0' VISAYAS 10° Mayo Bay D A V A O G U L F 6°30' 6°30' Davao MINDANAO del Sur 5° Nangan Bay 126°0' 120° 125° Abag Bay MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION SOURCES OF INFORMATION:Topographic information taken from NAMRIA Topographic Tagabibi Bay Map at a scale of 1:50,000. -

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR CONFIRMATION AND APPROVAL OF EMERGENCY CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROJECT, NAMELY: PURCHASE AND INSTALLATION OF NEW 10MVA POWER TRANSFORMER FOR BAGANGA SUBSTATION ERC CASE NO. 2020-010 RC DAVAO ORIENTAL Promulgated: ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, August 24, 2020 INC. (DORECO), Applicant. x ------------------------------------ x O R D E R On 10 March 2020, Davao Oriental Electric Cooperative, Inc. (DORECO) filed an Application dated 27 January 2020 seeking the Commission’s approval of its emergency Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) project for the purchase and installation of a new 10MVA transformer for Baganga Substation. The pertinent provisions of the said Application are hereunder quoted as follows: 1. DORECO is a non-stock, non-profit electric cooperative, duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with principal office at Madang National Highway, Barangay Central, City of Mati, Davao Oriental; 2. It holds an exclusive franchise issued by the National Electrification Commission, to operate an electric light and power distribution service in Mati City and certain municipalities of the province of Davao Oriental, namely: ERC CASE NO. 2020-010 RC ORDER/12 AUGUST 2020 PAGE 2 OF 11 San Isidro, Governor Generoso, Lupon, Banay-Banay, Tarragona, Manay, Caraga, Baganga, Cateel and Boston. LEGAL BASES FOR THE APPLICATION 3. Pursuant to Republic Act No. 9136, ERC Resolution 26, Series of 2009 and other laws and rules, and in line with its mandate to provide safe, quality, efficient and reliable electric service to its consumers, DORECO submits the instant application for the Honorable Commission’s confirmation and approval of its Emergency Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Project, namely: Purchase of New 10 MVA Power Transformer for Baganga Substation. -

Republic of the Philippines DAVAO ORIENTAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC (DORECO) City of Mati, Davao Oriental

Republic of the Philippines DAVAO ORIENTAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC (DORECO) City of Mati, Davao Oriental INVITATION TO APPLY FOR ELIGIBILITY AND TO BID The Davao Oriental Electric Cooperative, Inc. (DORECO) through its Bids and Award Committee (BAC), invites interested parties to apply for eligibility and if found eligible, to bid for the following: APPROVED COST OF BUDGET FOR BID LOT DESCRIPTION SOURCE OF FUND THE CONTRACT DOCS. LOT 1 NEA Subsidy Fund 10,992,860.27 25,000.00 Labor and Materials for the Construction of power distribution lines in District I (City of Mati) Sitios and Puroks LOT 2 Labor and Materials for the Construction NEA Subsidy Fund 5,042,422.72 10,000.00 of power distribution lines in District II (San Isidro/Gov. Generoso) Sitios and Puroks LOT 3 NEA Subsidy Fund 3,923,123.91 5,000.00 Labor and Materials for the Construction of power distribution lines in District III (Lupon/Banaybanay) Sitios and Puroks LOT 4 NEA Subsidy Fund 9,730,516.82 10,000.00 Labor and Materials for the Construction of power distribution lines in District IV (Tarragona/Manay) Sitios and Puroks LOT 5 NEA Subsidy Fund 5,129,622.55 10,000.00 Labor and Materials for the Construction of power distribution lines District V (Caraga/Baganga) Sitios and Puroks LOT 6 NEA Subsidy Fund 3,938,496.11 5,000.00 Labor and Materials for the Construction of power distribution lines District V (Cateel/Boston) Sitios and Puroks LOT 7 Supply of Distribution Transformers NEA Subsidy Fund 3,364,000.00 5,000.00 Lot 8 NEA Subsidy Fund 1,511,000.00 5,000.00 Supply of Meter, KWH, 1 Phase, Class 1, 240 V, 10 (60) A, Electronic, (Bottom Connected) All particulars relative to Eligibility Statement and Screening, Bid Security, Performance Security, Evaluation of Bids, Post Qualification and Award of Contract shall be in accordance with the IRR of RA 9184 and in accordance with the Guidelines on Public Bidding of RA 10531.