Women's Role and Support for the Closed Shing Season in the Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 15 Lgus with Highest Poverty Incidence, Davao Region, 2012)

Table 1. City and Municipal-Level Small Area Poverty Estimates (Top 15 LGUs with Highest Poverty Incidence, Davao Region, 2012) Rank Province Municipality Poverty Incidence (%) 1 Davao Occidental Jose Abad Santos (Trinidad) 75.5 2 Davao Occidental Don Marcelino 73.8 3 Davao del Norte Talaingod 68.8 4 Davao Occidental Saragani 65.9 5 Davao Occidental Malita 60.8 6 Davao Oriental Manay 58.1 7 Davao Oriental Tarragona 56.9 8 Compostela Valley Laak (San Vicente) 53.8 9 Davao del Sur Kiblawan 52.9 10 Davao Oriental Caraga 51.6 11 Davao Occidental Santa Maria 50.7 12 Davao del Norte San Isidro 43.2 13 Davao del Norte New Corella 41.6 14 Compostela Valley Montevista 40.2 15 Davao del Norte Asuncion (Saug) 39.2 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority Note: The 2015 Small Area Poverty Estimates is not yet available. Table 2. Geographically-Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas (GIDAs) PROVINCE/HUC CITY/MUNICIPALITY BARANGAYS Baganga Binondo, Campawan, Mahan-ob Boston Caatihan, Simulao Caraga Pichon, Sobreacrey, San Pedro Cateel Malibago Davao Oriental Gov. Generoso Ngan Lupon Don Mariano, Maragatas, Calapagan Manay Taokanga, Old Macopa Mati City Langka, Luban, Cabuaya Tarragona Tubaon, Limot Asuncion Camansa, Binancian, Buan, Sonlon IGaCoS Pangubatan, Bandera, San Remegio, Libertad, San Isidro, Aundanao, Tagpopongan, Kanaan, Linosutan, Dadatan, Sta. Cruz, Cogon Davao del Norte Kapalong Florida, Sua-on, Gupitan San Isidro Monte Dujali, Datu Balong, Dacudao, Pinamuno Sto. Tomas Magwawa Talaingod Palma Gil, Sto. Niño, Dagohoy Laak Datu Ampunan, Datu Davao Mabini Anitapan, Golden Valley Maco Calabcab, Elizalde, Gubatan, Kinuban, Limbo, Mainit, Malamodao, Masara, New Barili, New Leyte, Panangan, Panibasan, Panoraon, Tagbaros, Teresa Maragusan Bahi, Langgawisan Compostela Valley Monkayo Awao, Casoon, Upper Ulip. -

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

E1467 V 12 REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT of PUB1,IC WORKS and HIGHWAYS BONIFACIO DRIVE, PORT AREA, MANILA

E1467 v 12 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUB1,IC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS BONIFACIO DRIVE, PORT AREA, MANILA Public Disclosure Authorized FEASIBILITY STUDIES AND DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN OF REMEDIAL WORKS IN SPECIFIED LANDSLlDE AREAS AND ROAD SLIP SECTlONS IBRD-Assisted National Road Improvement and Management Program Loan No. 7006-PH Draft Final Report on the Environmental and Social Components DIGOS-GENERAL SANTOS ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized I Davao - Cal~nanRoad .#ha--#K*I Public Disclosure Authorized JAPAN OVERSEAS COlYSULTANTS CO, LTIk In association with ClRTEZ* DBYILOPYBYT CORPOMTlOW @ TECWNIKS GROUP CORPORATION REPUBLlC OF THE PHlLIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS BONIFAClO DRIVE, PORT AREA, MAhllLA FEASIBILITY STUDIES AND DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN OF REMEDIAL WORKS IN SPECIFIED LANDSLIDE AREAS AND ROAD SLIP SECTIONS IBRD-Assisted National Road Improvement and Management Program Loan No. 7006-PH Draft Final Report on the Environmental and Social Components DIGOS-GENERAL SANTOS ROAD Cebu Transcentral Road in association with CERIQA DeMLOCYENT COlMRATMN O) TECHMIKS GROUP CORPORATlOM TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE KEY MAP DIWS GENERAL SANTOS ROAD Figure 1-1 1.0 GENERAL STATEMENT 1-1 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS 2.1 Location 2.2 Objectives 2.3 Coverage and Scope 3.0 ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ROAD INFLUENCE AREA 3.1 Local Geography and Landuse 3.2 Topography and Climate 3.3 Soil Types 4.0 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PROFILES OF THE ROAD IMPACT AREA 4.1 Davao del Sur Road Segment 4.2 Sarangani Road Segment 4.3 General Santos City Road Segment 5.0 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCNMANAGEMENT PLAN (Em) Construction Related Impacts Operation Related Impacts Environmental Compliance Requirement Waste Management and Disposal Strategy Contingency Response Strategy Abandonment Strategy Environmental Monitoring Strategy Construction Contractor's Environmental Program Table of Contents: cont 'd.. -

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support I. REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Davao Region still needs to improve its infrastructure facilities and services. While the Davao International Airport has been recently completed, road infrastructure, seaport, and telecommunication facilities need to be upgraded. Flood control and similar structures are needed in flood prone areas while power and water supply facilities are still lacking in the region’s remote and underserved areas. While the region is pushing for increased production of staple crops, irrigation support facilities in major agricultural production areas are still inadequate. Off-site infrastructure in designated tourism and agri-industrial areas are likewise needed to encourage investment and spur economic activities. Accessibility and Mobility through Transport There is a need for the construction of new roads and improvement of the existing road network to provide better access and linkage within and outside the Region as an alternate to existing arterial and local roads. The lack of good roads in the interior parts of the municipalities and provinces connecting to major arterial roads constrains the growth of agriculture and industry in the Region; it also limits the operations of transport services due to high maintenance cost and longer turnaround time. Traffic congestion is likewise becoming a problem in highly urbanized and urbanizing areas like Davao City and Tagum City. While the Region is physically connected with the adjoining regions in Mindanao, poor road condition in some major highways also hampers inter-regional economic activities. The expansion of agricultural activities in the resettlement and key production areas necessitates the opening and construction of alternative routes and farm-to-market roads. -

Notice of Award Department of Public Works And

o Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS DAVAO OCCIDENTAL DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE REGION XI Brgy. Buhangin, Malita, Davao Occidental Contract ID : 18LE0032 Contract Name : Construction of Mini Gymnasium Location: Kinanga ES, Brgy. Kinanga, Don Marcelino, Davao Occidental NOTICE OF AWARD March 6, 2018 The Proprietor/Manager R. SEMILLA CONSTRUCTION AND MKTG. Dona Segunda Bldg., CM. Recto St. Davao City Dear Sir/Madame: We hereby accept your bid for the above-stated Contract and, therefore, award the Contract to you, as the Bidder with the Lowest Calculated Responsive Bid, at a total Contract price equivalent to ONE MILLION ONE HUNDRED EIGHTY TWO THOUSAND NINE HUNDRED NINETY TWO PESOS & 57/100 (Php 1,182,992.57) to be completed within SIXTY (60) calendar days. You are, therefore required, within ten (10) calendar days from your receipt of this Notice of Award, to submit to us the following documents as conditions for the signing of the Contract: a.Notice of Award (NOA) with the bidder's signed "conforme" b.Authority of Signing Official/Board Resolution/Secretary's Certificate c.For a joint venture (JV), Contractor's PCAB Special IV License and JV Agreement. d.Performance Security in any of the forms specified in the Instructions to Bidders (Use Form DPWH-INFR-43 or DPWH-INFR-44, as applicable). e.Construction Methods (Use Form DPWH-INFR-45) f.Construction Schedule in the Form of PERT/CPM Diagram or Precedence Diagram and Bar Chart with S-Curve and Cash Flow (Use Form DPWH-INFR-46). g.Manpower Schedule (Use Form DPWH-INFR-47). -

Cooperative Learning Application to CAI (Computer- Assisted Instruction)

CIVIL REGISTRATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY: PROBING ICT SUSTAINABILITY JANN BLAIR P. SALINAS Administrative Officer I Davao Oriental Provincial Statistical Office Philippine Statistics Authority [email protected] | 09171039405 ABSTRACT Pursuant to Republic Act 7160, Local Civil Registry Offices (LCROs) are created in each city or municipality to carry out the civil registration functions of the Local Government Unit (LGU). Civil registration is the system by which a government records the vital events of its citizens and residents. Over the last few decades, organizations have shown increased interest in deploying information technology (I.T.) in office environments for they are being challenged with the changes brought by technological innovations. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) started to embrace the changes brought by this innovation through the development of software programs for use by LCROs. This study was mainly undertaken to determine the sustainability of implementing the above-mentioned I.T. resources developed by PSA and the factors affecting its implementation. Data were gathered using a semi-structured interview questionnaire. Follow- up interviews and observations were conducted to gather additional data to strengthen initial results. Data were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. Results revealed that BREQS and CRIS are currently being used by 64% of the LCROs in Davao Oriental while PhilCRIS is currently being used by 91% of the LCROs. Additionally, BREQS, CRIS and PhilCRIS are currently being used by LCROs for an average of 8.8, 14.0 and 2.9 years, respectively. Using these systems, problems are being encountered including bugs/errors of the system and lack of trainings for the in-charge of the system implementation in the LCRO. -

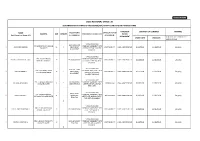

Dole Regional Office Xi Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries Monitoring Form

DOLE-GIP_Form C DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE XI GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES MONITORING FORM NATURE OF DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS NAME EDUCATIONAL OFFICE/PLACE OF ADDRESS AGE GENDER DOCUMENTS SUBMITTED WORK/ (Last Name, First Name, MI) ATTAINMENT ASSIGNMENT ASSIGNMENT (e.g. Contract completed or START DATE END DATE preterminated *APPLICATION FORM BS IN HOTEL AND 678, MANGUSTAN ST., MADAUM, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 1 ALIVIO, FEMAE JEAN B. 23 F RESTAURANT W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going TAGUM CITY CERTIFICATE *TOR *ACCIDENT MANAGEMENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM PRK. 19-B, KATIPUNAN, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 2 BALIENTES, MARIA KATHLEEN G. 20 F BS IN ACCOUNTING W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going MADAUM, TAGUM CITY CERTIFICATE *SPR *ACCIDENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM BS IN HOTEL AND PRK. 5-A, APOKON, TAGUM *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 3 CANTILA, GEBBIE M. 20 F RESTAURANT W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/19/2018 11/17/2018 On going CITY, DAVAO DEL NORTE CERTIFICATE *DIPLOMA MANAGEMENT *ACCIDENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM PRK. 1, TANGLAW, BE DUJALI, BS IN BUSINESS *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 4 ESTAÑOL, ANNA MAE D. 21 F W/IN BE DUJALI CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going DAVAO DEL NORTE ADMINISTRATION CERTIFICATE *DIPLOMA/TOR *BRGY. CERT *APPLICATION FORM BACHELOR OF PRK. 4, NARRA, GABUYAN, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 5 LOPEZ, MARYJAN P. 23 SECONDARY W/IN KAPALONG CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going KAPALONG, DAVAO DEL NORTE CERTIFICATE *MARRIAGE CERT., EDUCATION *TOR *CERT OF INDIGENCY M *APPLICATION FORM PRK. -

TIER1 Agency: BUREAU of JAIL MANAGEMENT and PENOLOGY

TIER1 Agency: BUREAU OF JAIL MANAGEMENT AND PENOLOGY (BJMP) XI INVESTMENT BRIEF SPATIAL COVERAGE RDP RESULTS PROGRAMS/PROJECTS/ TARGETS (IN SOURCE OF UACS PROGRAM/PROJECT MATRIX (RM) REMARKS ACTIVITIES CONGRESSIONAL PHP'000) FUNDS DESCRIPTION PROVINCE ADDRESSED DISTRICT 2019 MFO: SAFEKEEPING & DEVELOPMENT OF INMATES (i) Security Management of Inmates: Provision of Escorting Services, Conduct of Regionwide Inspections, Davao City/Del Travel Expenses 1st 713.77 GAA personnel inventories & Sur local travels for official businesses: Military Supplies Regionwide 181.50 GAA Fuel, Oil, Lubricant Regionwide 2,178.00 GAA Expenses (ii) Improvement and Maintenance of Jail Water Expenses Regionwide 7,920.00 GAA Facilities & Equipment: Electricity Expenses Regionwide 9,900.00 GAA Repair/Improvement - Davao City/Del 1st _ GAA Davao City Jail Sur Repair/Improvement - Davao City/Del 1st _ GAA Davao City Female Jail Sur Repair/Improvement - Davao City/Del 1st _ GAA Davao City Jail-Annex Sur Repair/Improvement - Digos City District Del Sur 1st _ GAA Female Jail 6-1 INVESTMENT BRIEF SPATIAL COVERAGE RDP RESULTS PROGRAMS/PROJECTS/ TARGETS (IN SOURCE OF UACS PROGRAM/PROJECT MATRIX (RM) REMARKS ACTIVITIES CONGRESSIONAL PHP'000) FUNDS DESCRIPTION PROVINCE ADDRESSED DISTRICT 2019 Repair/Improvement - Del Norte 2nd _ GAA Panabo City District Jail Repair/Improvement - Del Norte 1st _ GAA Tagum City Jail Repair/Improvement - Del Norte _ GAA IGACOS City Jail Repair/Improvement - Oriental 2nd 300.00 GAA Lupon District City Jail Repairs/ Maintenance Regionwide 260.15 -

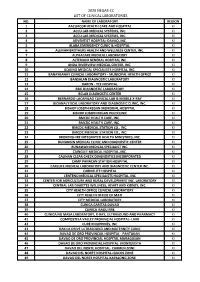

2020 Neqas-Cc List of Clinical Laboratories No

2020 NEQAS-CC LIST OF CLINICAL LABORATORIES NO. NAME OF LABORATORY REGION 1 AACUACOR HEALTH CARE AND HOSPITAL XI 2 ACCU LAB MEDICAL SYSTEMS, INC. XI 3 ACCU LAB MEDICAL SYSTEMS, INC. XI 4 ADVENTIST HOSPITAL-DAVAO, INC. XI 5 ALABA EMERGENCY CLINIC & HOSPITAL XI 6 ALEXIAN BROTHERS HEALTH AND WELLNESS CENTER, INC. XI 7 ALPHACARE MEDICAL LABORATORY XI 8 ALTERADO GENERAL HOSPITAL INC. XI 9 ANDA RIVERVIEW MEDICAL CENTER, INC. XI 10 AQUINO MEDICAL SPECIALISTS HOSPITAL, INC. XI 11 BANAYBANAY CLINICAL LABORATORY - MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE XI 12 BANSALAN DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY XI 13 BARON - YEE HOSPITAL XI 14 BBG DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY XI 15 BCLAB DIAGNOSTIC CENTER XI 16 BERNARDO-LACANILAO CLINICAL LAB & MOBILE X-RAY XI 17 BIOANALYTICAL LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC, INC. XI 18 BISHOP JOSEPH REGAN MEMORIAL HOSPITAL XI 19 BISHOP JOSEPH REGAN POLYCLINIC XI 20 BMCDC HEALTH CARE, INC. XI 21 BMCDC HEALTH CARE, INC. XI 22 BMCDC MEDICAL STATION CO., INC. XI 23 BMCDC MEDICAL STATION CO., INC. XI 24 BROKENSHIRE INTEGRATED HEALTH MINISTRIES, INC. XI 25 BUHANGIN MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER XI 26 BUNAWAN MEDICAL SPECIALIST INC. XI 27 CAINGLET MEDICAL HOSPITAL, INC. XI 28 CALINAN CLEAR CHECK DIAGNOSTICS INCORPORATED XI 29 CAMP PANACAN STATION HOSPITAL XI 30 CARELIFE MEDICAL LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER INC. XI 31 CARMELITE HOSPITAL XI 32 CENTENO MEDICAL SPECIALISTS HOSPITAL, INC XI 33 CENTER FOR AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT INC. LABORATORY XI 34 CENTRAL LAB DIABETES WELLNESS, HEART AND KIDNEY, INC. XI 35 CITY HEALTH OFFICE CLINICAL LABORATORY -

Sitecode Region Penro Cenro Barangay Municipality Name of Organization Contact Person Commodity Hectares

AREA IN SITECODE REGION PENRO CENRO BARANGAY MUNICIPALITY NAME OF ORGANIZATION CONTACT PERSON COMMODITY HECTARES Ancestral Domain Tribal Farmers Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Upper Ulip Monkayo Association Mauricio Latiban Trees, Rubber, Timber 75 Barangay Tribal Council of Elders & Leaders Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo San Jose Monkayo of San Jose (BTCEL San Jose) Romeo Capao Rubber, Timber 50 Camanlangan Tree Growers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Camanlangan New Bataan (CATREGA) Ruperto Sabay Sr. Timber 50 Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Casoon Monkayo Casoon Tree Farmers Association (CATFA) Gavino Ayco Timber 80 Dalaguete Lebanon San Vicente Montevista Watershed Farmers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Lebanon Montevista (DALESANMWFA) Martiniano Paniamogan Timber 37 XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Ngan Compostela Kapwersa Comval Agricultural Cooperative Alejandro Cacao, Timber 50 Magangit Upland Farmers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Fatima New Bataan (MAUFA) Clemente T. Nabor Timber 50 Mangayon Indigenous People and Farmers Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Mangayon Compostela Association (MIPFA) Timber 70 Maragusan Waterworks & Sanitation Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Poblacion Maragusan Cooperative (MAWASCO) Cesar Escuadro Trees, Timber 100 Mayaon Upland Small Farmers Association Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Mayaon Montevista (MUSFA) -

Title Community Initiated Dugong Conservation in Cape San Agustin

Community initiated dugong conservation in Cape San Agustin Title (SEASTAR2000) Author(s) DAGONDON, GLICETO O. Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Citation SEASTAR2000 and Asian Bio-logging Science (The 10th SEASTAR2000 workshop) (2011): 61-64 Issue Date 2011-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/138574 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Community initiated dugong conservation in Cape San Agustin GLICETO O. DAGONDON Executive Director, GREEN Mindanao Association Inc. (GMAI) 9000 Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines Email : [email protected] ABSTRACT The dugong conservation project in Cape San Agustin started about a year ago focused on community monitoring, visual sighting and photography of dugong. The results recorded active time of day dugongs were sighted, numbers, and activities as well death, stranding and recovery efforts. Dugongs were tracked across Cape San Agustin from Pujada. Associated information was gathered from the Samal-Talikud islands and Malita Bay in Davao Gulf about 100 kilometers away towards Celebes Sea. Sightings were also noted within the 100-kilometers between Baganga Bay and Hinatuan Bay towards the eastern Pacific seaboard since 2004. Sightings, strandings, deaths and recovery efforts were similarly reported in all these areas. These areas have a potential link with the southern Mindanao-Sulu-Celebes Sea area of dugong, marine mammals and endangered wildlife community. KEYWORDS: GMAI, PCRA, Barangay, DHS, MPA, CRM, PFARO INTRODUCTION and recording dugong sightings and cases of Dugong stranding and deaths were first known in stranding in Pujada Bay towards Cape San Agustin Hinatuan Bay, Surigao del Sur in 2003 among local (Fig. 1) near Davao Gulf. -

Chapter 28 Future Traffic Demand Forecast For

CHAPTER 28 FUTURE TRAFFIC DEMAND FORECAST FOR TDG CHAPTER 28 FUTURE TRAFFIC DEMAND FORECAST OF TDG 28.1 ANALYSES OF TRAFFIC SURVEY RESULTS This chapter describes the OD survey results. Other traffic survey results were discussed in Chapter 26. 28.1.1 Traffic Characteristics (1) General Roadside OD survey was conducted at six (6) stations. A number of samples and sample rate is shown in Table 28.1-1. TABLE 28.1-1 ROADSIDE OD SURVEY STATION AND SAMPLE RATE No. of Sample No. Road Name Location AADT Sample Rate Tagum & Mawab 1 Davao-Surigao Road 1090 3899 28.0% Boundary Davao City & Panabo 2 Davao-Surigao Road 978 1096 8.9% Boundary 3 Davao-Bukidnon Road Calinan & Marilog 743 2977 25.0% 4 Davao-Digos Road Toril & Sta. Cruz 1045 6811 15.3% Malugon & Gen. Santos 5 Davao-General Santos Road 1002 7244 13.8% Boundary Gen. Santos & 6 General Santos-Cotabato Road 1014 6956 14.6% Polomolok Boundary Average 982 6475 15.1% (2) Traffic Characteristics Trip purpose is estimated through the OD data as illustrated in Figure 28.1.1-1. Of the total vehicle trips 63% were ‘Business’ trips, 28% were ‘Private’ trips. To/From Work 3% Leisure/Tourism To/From School 1% Others 1% 4% Private 28% Business 63% FIGURE 28.1.1-1 TRIP PURPOSE 28-1 (3) Average Number of Passengers by Vehicle Category Vehicle OD is linked to passenger OD through the average number of passenger on board by type of vehicles as the vehicle occupancy rate. Table 28.1.1-2 shows the average number of passenger on board by type of vehicles.