Cepf Final Project Completion Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

First Quarter of 2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Macroeconomic Performance . 1 Inflation . 1 Consumer Price Index . 1 Purchasing Power of Peso . 2 Labor and Employment . 2 II. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Sector Performance . 3 Crops . 3 Palay . 3 Corn . 3 Fruit Crops . 4 Vegetables . 4 Non-food and Industrial and Commercial Crops . 5 Livestock and Poultry . 5 Fishery . 6 Forestry . 6 III. Trade and Industry Services Sector Performance . 8 Business Name Registration . 8 Export . 8 Import . 9 Manufacturing . 9 Mining . 10 IV. Services Sector Performance . 11 Financing . 11 Tourism . 12 Air Transport . 12 Sea Transport . 13 Land Transport . 13 V. Peace and Security . 15 VI. Development Prospects . 16 MACROECONOMIC PERFORMANCE Inflation Rate Figure 1. Inflation Rate, Caraga Region The region’s inflation rate continued to move at a slower pace in Q1 2019. From 4.2 percent in December 2018, it declined by 0.5 percentage point in January 2019 at 3.7 percent (Figure 1) . It further decelerated in the succeeding months, registering 3.3 percent in February and 2.9 percent in March. This improvement was primarily due to the slow movement in the monthly increment in the price Source: PSA Caraga indices of heavily-weighted commodity groups, such as food and non-alcoholic beverages; Figure 2. Inflation Rate by Province housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels; and transport. The importation of rice somehow averted the further increase in the market price of rice in the locality. In addition, the provision of government subsidies particularly to vulnerable groups (i.e. DOTr’s Pantawid Pasada Program) and free tuitions under Republic Act No. -

Typhoon Bopha (Pablo)

N MA019v2 ' N 0 ' Silago 3 0 ° 3 0 ° 1 0 Philippines 1 Totally Damaged Houses Partially Damaged Houses Number of houses Number of houses Sogod Loreto Loreto 1-25 2-100 717 376 Loreto Loreto 26-250 101-500 San Juan San Juan 251-1000 501-1000 1001-2000 1001-2000 2001-4000 2001-4000 Cagdianao Cagdianao 1 N ° N San Isidro 0 ° Dinagat 1 0 Dinagat San Isidro Philippines: 1 5 Dinagat (Surigao del Norte) Dinagat (Surigao 5 del Norte) Numancia 280 Typhoon Bopha Numancia Pilar Pilar Pilar Pilar (Pablo) - General 547 Surigao Dapa Surigao Dapa Luna General Totally and Partially Surigao Surigao Luna San San City Francisco City Francisco Dapa Dapa Damaged Housing in 1 208 3 4 6 6 Placer Placer Caraga Placer Placer 10 21 Bacuag Mainit Bacuag (as at 9th Dec 5am) Mainit Mainit 2 N 1 Mainit ' N 0 ' 3 0 ° Map shows totally and partially damaged 3 9 Claver ° 9 Claver housing in Davao region as of 9th Dec. 33 Bohol Sea Kitcharao Source is "NDRRMC sitrep, Effects of Bohol Sea Kitcharao 10 Typhoon "Pablo" (Bopha) 9th Dec 5am". 3 Province Madrid Storm track Madrid Region Lanuza Tubay Cortes ! Tubay Carmen Major settlements Carmen Cortes 513 2 127 21 Lanuza 10 Remedios T. Tandag Tandag City Tandag Remedios T. Tandag City Romualdez 3 Romualdez 15 N ° N 13 9 ° Bayabas 9 Buenavista Sibagat Buenavista Sibagat Bayabas Carmen Carmen Butuan 53 200 Butuan 127 Butuan 21 Butuan 3 City City Cagwait Cagwait 254 Prosperidad 12 17 Gingoog Buenavista 631 Gingoog Buenavista Marihatag Marihatag 43 1 38 19 San Las Nieves San Agustin Las Nieves Agustin 57 Prosperidad 56 2 4 0 10 -

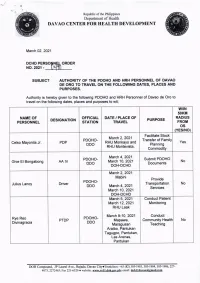

DAVAO CENTER for HEALTH DEVELOPMENT Os

Republic of the Philippines /O" O\ Department of Health o DAVAO CENTER FOR HEALTH DEVELOPMENT Match 02,2021 DCHD PERSO N ORDER NO.202t - SUBJECT AUTHORITY OF THE POOHO AND HRH PERSONNEL OF DAVAO DE ORO TO TRAVEL ON THE FOLLOYUNG DATES, PLACES AND PURPOSES. Authority is hereby given to the following PDOHO and HRH Personnel of Davao de Oro to travel on the following dates, places and purposes to wit; wflN 50KU NATUIE OF OFFICIAL DATE / PLACE OF RADlUS DESIGNATION PURPOSE PERSONNEL STATION TRAVEL FROT os (YES/NO) Facilitate Stock March2,2021 PDOHO- Transfer of Family Celso Mayonila Jr. PDP RHU Monkayo and Yes DDO Planning RHU Montevista, Commodity March 4,2Q21 PDOHO- Submit PDOHO Ghie El Bongabong AA IV March 10, 2021 No DDO Documents DOH-DCHD March 2,2021 Mabini Provide PDOHO. Julius Lanoy Driver Transportation No DDO March 4,2021 Services March'10, 2021 DOH-DCHD March 5, 2021 Conduct Patient March 12,2021 Monitoring RHU Laak March 9-10, 2021 Conduct Rye Reo PDOHO- PTDP Mapawa, Community Health No Divinagracia DDO Maragusan Teaching Araibo, Pantukan Tagugpo, Pantukan, Las Arenas, Pantukan DOH Compound, JP laurel Ave., Bajada Davao City.Trunklines: +63 (E2) 305-1903, 305-1904, 305'1906,22'l- 4073,2272463iFu.221{320 o website: g44g4q[!!9[.ggy,p!; email: dg.b!149r!@4Ed!g, Republic of the Philippines .a" D. Department of Health .E:; o DAVAO CENTER FOR HEALTH DEVELOPIVTENT Conduct Technical Assistance regarding COVID 19 Reporting of Newly Hired PDOHO- March 9-10, 2021 Jason Mayang DSO Encoder No DDO RHU Maragusan Surveillance Functionality Assessment -

Philippine Independence Day Issue

P Philippine Independence Day Issue Editor’s Notes: ………………………… “Happy Independence Day, Philippines!” ……………………. Eddie Zamora Featured Items: 1. Philippine Independence Day, A Brief History ……………………………………………………………………….. The Editor 2. I Am Proud To Be A Filipino ……………………………………………………………………….. by Nelson Lagos Ornopia, Sr. 3. Presidents Of The Philippines ……………………………………………………………..………………………………. Group Effort 4. The Philippine Flag and Its Symbols ……………………………………………………………………………………. The Internet 5. The Philippine National Anthem …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SULADS Corner: …………………………..………………… “Sulads Is Like A Rose” ………………… by Crisophel Abayan. NEMM Patch of Weeds: …………………………………………………………………………….……………………………..………….. Jesse Colegado LIFE of a Missionary: ………………… “President of SDA Church Visits ‘Land Eternal’”………..………. Romulo M. Halasan CLOSING: Announcements |From The Mail Bag| Prayer Requests | Acknowledgements Meet The Editors |Closing Thoughts | Miscellaneous Happy Independence Day, Philippines! very June 12 the Philippines celebrates its Independence Day. Having lived in America some 30 E years now I am familiar with how people celebrate Independence here—they have parades, barbecues and in the evening fireworks. When we left the Philippines years ago fireworks were banned in the country. I don’t know how it is today. It would be wonderful if Filipinos celebrated Independence Day similar to or better than the usual parades, picnics, barbecues and some fireworks. When I was a kid growing up, Independence Day was observed on July 4th, the day when the United States granted the country independence from American rule. The American flag was finally lowered from government building flagpoles and the Philippine flag was hoisted in its stead. From that day until one day in 1962 the country celebrated Independence Day on the same day the United States celebrated its own Independence Day. But on May 12, 1962 then President Diosdado Macapagal issued Presidential Proclamation No. -

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 48 Flooding & Landslides 21Jan2011

FB FINELY (Half-submerged off Diapila Island, El Nido, Palawan - 18 January 2011) MV LUCKY V (Listed off the Coast of Aparri, Cagayan - 18 Jan) The Pineapple – a 38-footer Catamaran Sailboat twin hulled (white hull and white sails) departed Guam from Marianas Yatch Club 6 January 2011 which is expected to arrive Cebu City on 16 January 2011 but reported missing up to this time Another flooding and landslide incidents occurred on January 16 to 18, 2011 in same regions like Regions IV-B, V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and ARMM due to recurrence of heavy rains: Region IV-B Thirteen (13) barangays were affected by flooding in Narra, Aborllan, Roxas and Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Region V Landslide occurred in Brgy. Calaguimit, Oas, Albay on January 20, 2011 with 5 houses affected and no casualty reported as per report of Mayor Gregorio Ricarte Region VII Brgys Poblacion II and III, Carcar, Cebu were affected by flooding with 50 families affected and one (1) missing identified as Sherwin Tejada in Poblacion II. Ewon Hydro Dam in Brgy. Ewon and the Hanopol Hydro Dam in Brgy. Hanopol all in Sevilla, Bohol released water. Brgys Bugang and Cambangay, Brgys. Napo and Camba in Alicia and Brgys. Canawa and Cambani in Candijay were heavily flooded Region VIII Brgys. Camang, Pinut-an, Esperanza, Bila-tan, Looc and Kinachawa in San Ricardo, Southern Leyte were declared isolated on January 18, 2011 due to landslide. Said areas werer already passable since 19 January 2011 Region IX Brgys San Jose Guso and Tugbungan, Zamboanga City were affected by flood due to heavy rains on January 18, 2011 Region X One protection dike in Looc, Catarman. -

DSWD DROMIC Report #5 on Tropical Depression “VICKY” As of 22 December 2020, 6PM

DSWD DROMIC Report #5 on Tropical Depression “VICKY” as of 22 December 2020, 6PM Situation Overview On 18 December 2020, Tropical Depression “VICKY” entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) and made its first landfall in the municipality of Banganga, Davao Oriental at around 2PM. On 19 December 2020, Tropical Depression “VICKY” made another landfall in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan and remained a tropical depression while exiting the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) on 20 December 2020. Source: DOST-PAGASA Severe Weather Bulletin I. Status of Affected Families / Persons A total of 31,408 families or 130,855 persons were affected in 290 barangays in Regions VII, VIII, XI and Caraga (see Table 1). Table 1. Number of Affected Families / Persons NUMBER OF AFFECTED REGION / PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY Barangays Families Persons GRAND TOTAL 290 31,408 130,855 REGION VII 32 618 2,510 Bohol 3 15 60 Candijay 3 15 60 Cebu 15 441 1,812 Argao 1 15 45 Boljoon 2 13 44 Compostela 2 54 221 Dalaguete 1 2 8 Danao City 1 150 600 Dumanjug 1 20 140 Lapu-Lapu City (Opon) 4 163 662 Sibonga 3 24 92 Negros Oriental 14 162 638 Bais City 3 33 125 Dumaguete City (capital) 6 92 365 City of Tanjay 5 37 148 REGION VIII 2 12 38 Leyte 2 12 38 MacArthur 1 10 34 Mahaplag 1 2 4 REGION XI 22 608 2,818 Davao de Oro 13 294 1,268 Compostela 2 10 37 Mawab 1 7 20 Monkayo 3 72 360 Montevista 1 13 65 Nabunturan (capital) 4 152 546 Pantukan 2 40 240 Davao del Norte 8 310 1,530 Asuncion (Saug) 6 238 1,180 Kapalong 1 12 50 New Corella 1 60 300 Davao Oriental 1 4 20 Cateel 1 4 20 CARAGA 234 30,170 125,489 Page 1 of 9 | DSWD DROMIC Report #5 on Tropical Depression “VICKY” as of 22 December 2020, 6PM NUMBER OF AFFECTED REGION / PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY Barangays Families Persons Agusan del Norte 30 1,443 6,525 Butuan City (capital) 16 852 4,066 City of Cabadbaran 9 462 2,007 Jabonga 2 38 119 Las Nieves 1 10 50 Remedios T. -

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support I. REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Davao Region still needs to improve its infrastructure facilities and services. While the Davao International Airport has been recently completed, road infrastructure, seaport, and telecommunication facilities need to be upgraded. Flood control and similar structures are needed in flood prone areas while power and water supply facilities are still lacking in the region’s remote and underserved areas. While the region is pushing for increased production of staple crops, irrigation support facilities in major agricultural production areas are still inadequate. Off-site infrastructure in designated tourism and agri-industrial areas are likewise needed to encourage investment and spur economic activities. Accessibility and Mobility through Transport There is a need for the construction of new roads and improvement of the existing road network to provide better access and linkage within and outside the Region as an alternate to existing arterial and local roads. The lack of good roads in the interior parts of the municipalities and provinces connecting to major arterial roads constrains the growth of agriculture and industry in the Region; it also limits the operations of transport services due to high maintenance cost and longer turnaround time. Traffic congestion is likewise becoming a problem in highly urbanized and urbanizing areas like Davao City and Tagum City. While the Region is physically connected with the adjoining regions in Mindanao, poor road condition in some major highways also hampers inter-regional economic activities. The expansion of agricultural activities in the resettlement and key production areas necessitates the opening and construction of alternative routes and farm-to-market roads. -

Cooperative Learning Application to CAI (Computer- Assisted Instruction)

CIVIL REGISTRATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY: PROBING ICT SUSTAINABILITY JANN BLAIR P. SALINAS Administrative Officer I Davao Oriental Provincial Statistical Office Philippine Statistics Authority [email protected] | 09171039405 ABSTRACT Pursuant to Republic Act 7160, Local Civil Registry Offices (LCROs) are created in each city or municipality to carry out the civil registration functions of the Local Government Unit (LGU). Civil registration is the system by which a government records the vital events of its citizens and residents. Over the last few decades, organizations have shown increased interest in deploying information technology (I.T.) in office environments for they are being challenged with the changes brought by technological innovations. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) started to embrace the changes brought by this innovation through the development of software programs for use by LCROs. This study was mainly undertaken to determine the sustainability of implementing the above-mentioned I.T. resources developed by PSA and the factors affecting its implementation. Data were gathered using a semi-structured interview questionnaire. Follow- up interviews and observations were conducted to gather additional data to strengthen initial results. Data were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. Results revealed that BREQS and CRIS are currently being used by 64% of the LCROs in Davao Oriental while PhilCRIS is currently being used by 91% of the LCROs. Additionally, BREQS, CRIS and PhilCRIS are currently being used by LCROs for an average of 8.8, 14.0 and 2.9 years, respectively. Using these systems, problems are being encountered including bugs/errors of the system and lack of trainings for the in-charge of the system implementation in the LCRO. -

PROVINCIAL FISHERIES PROFILE Province of Compostela Valley

PROVINCIAL FISHERIES PROFILE Province of Compostela Valley I. GENERAL INFRORMATION** Total Land Area No.of Coastal Coastal Municipality Population (source No.of Barangay PPDO,Comval) (sq.km.) Barangay Population District 1 Maragusan 55,503 394.29 24 New Bataan 47,470 688.60 16 Compostela 81,934 187.50 16 Montevista 39,602 265.0 20 Monkayo 94,627 692.89 21 District 11 Nabunturan 73,196 245.29 28 Mawab 35,698 169.52 11 Laak 70,856 947.06 40 Maco 72,235 244.40 37 7 18,680 Mabini 36,807 412.25 11 6 20,286 Pantukan 79,067 420.13 13 9 51,352 TOTAL 687,195 4,666.93 237 22 90,318 II. FISHERY RESOURCES A. COMMERCIAL FISHERIES a. No.of Extension Worker Assigned……………………None b. No. of Commercial Fishing Vessel ( Catchers)……….None c. No. of Commercial Fishing Vessel (Registered)………None d. Total Annual Production (M.T./yr)……………………None e. No. of Licensed Commercial Fishermen………………None B. MUNICIPAL FISHERIES B.1 CAPTURE MUNICIPAL ** Municipality No.of Extension No.of No.of No.of Total No. of Total No.of Total Workers Assigned Fishermen Fishermen Motorized Annual non- Annual Fish Annual (Full time) (Part Banca Production Motorized Production Coral Production time) (M.T./Yr.) Banca (M.T./Yr.) (M.T./Yr.) Maco 2 (Alix Bellena & 180 115 150 200 122 95 3 1.5 Hanida Fernandez Mabini 2 (Amalia C. Bama 200 91 135 100 85 25 21 8 & Godofredo Fulo) Pantukan 2 (Bernardo G. Saga 456 142 410 775.79 188 180.55 9 2.84 & Lominicop Mambering TOTAL 836 348 695 1,145.79 395 365.55 33 12.34 B.2 INLAND MUNICIPAL *** Municipality Lake (ha.) River (ha.) Dams (ha.) SWIP (ha.) -

A Case Study on Indigenous Herbal Medicines

Ethnomedical documentation of and community health education for selected Philippine ethnolinguistic groups: the Mansaka people of Pantukan and Maragusan Valley, Compostela Valley Province, Mindanao, Philippines A collaborative project of Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care, Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila University of the Philippines Manila, Ermita, Manila University of the Philippines Mindanao, Bago Oshiro, Davao City 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive summary 1 Introduction 2 Objectives 3 Methodology 4 Results and discussion 7 Recommendations 21 References 22 Appendices 23 Tables Table 1. Materia medica Table 2. Mansaka terms Table 3. Mansaka demography ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We wish to acknowledge and express our heartfelt gratitude to the following people and organizations who have been significant partners in the undertaking of this research study: UP Mindanao Planning and Development Office for guidance and monitoring of the project; Mayor Jovito Derla and Municipal Assistant Administrator Mr Romeo Ang of Pantukan for permitting the research and helping in the selection of site; Mayor Gerome Lamparas of Maragusan Valley for permitting the research studies in the area; Barangay Captain Felicisimo C Marbones, Barangay Councilor and Matikadung Laurencio Camana of Barangay Napnapan for permitting the research to be conducted in Napnapan, Pantukan, Compostela Valley Province; Informants, contacts and guides from Maragusan and Pantukan communities for the support and unselfish sharing of their indigenous knowledge; Researcher’s family, friends and loved ones for their spiritual support through prayers for the safety during the one-year conduct of the research; and Above all, the Almighty God, to Whom all things were made possible. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An ethnopharmacological study of the Mansaka people in the municipalities of Pantukan and Maragusan Valley, Compostela Valley Province was conducted in June 1999 to May 2000. -

PHI-OCHA Logistics Map 04Dec2012

Philippines: TY Bopha (Pablo) Road Matrix l Mindanao Tubay Madrid Cortes 9°10'N Carmen Mindanao Cabadbaran City Lanuza Southern Philippines Tandag City l Region XIII Remedios T. Romualdez (Caraga) Magallanes Region X Region IX 9°N Tago ARMM Sibagat Region XI Carmen (Davao) l Bayabas Nasipit San Miguel l Butuan City Surigao Cagwait Region XII Magsaysay del Sur Buenavista l 8°50'N Agusan del Norte Marihatag Gingoog City l Bayugan City Misamis DAVAO CITY- BUTUAN ROAD Oriental Las Nieves San Agustin DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA MONKAYO TRENTO SAN FRANS BUTUAN DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Prosperidad TAGUM CITY 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA 102km/2.5hr 42km/1.5hr 12km/15mns 8°40'N 120km/2.45hr 60km/1hr 30km/45mns. 18kms/15mns Claveria Lianga MONKAYO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr 40km/1hr 22km/30mns Esperanza TRENTO SAN FRANCISCO 200km/4hr 140km/3 hr 110km/2.5hr 98km/2.hr 80km/1.45hr 58km/1.5hr BUTUAN 314km/6hr 254km/5hr 224km/4hr 212km/3.5hr 194km/3hr 172km/2.45hr 114km/2hr l Barobo l 8°30'N San Luis Hinatuan Agusan Tagbina del Sur San Francisco Talacogon Impasug-Ong Rosario 8°20'N La Paz l Malaybalay City l Bislig City Bunawan Loreto 8°10'N l DAVAO CITY TO - LORETO, AGUSAN DEL SUR ROAD DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN TRENTO STA. JOSEFA VERUELA LORETO DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Lingig TAGUM CITY Cabanglasan Trento 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN Veruela Santa Josefa TRENTO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr STA.