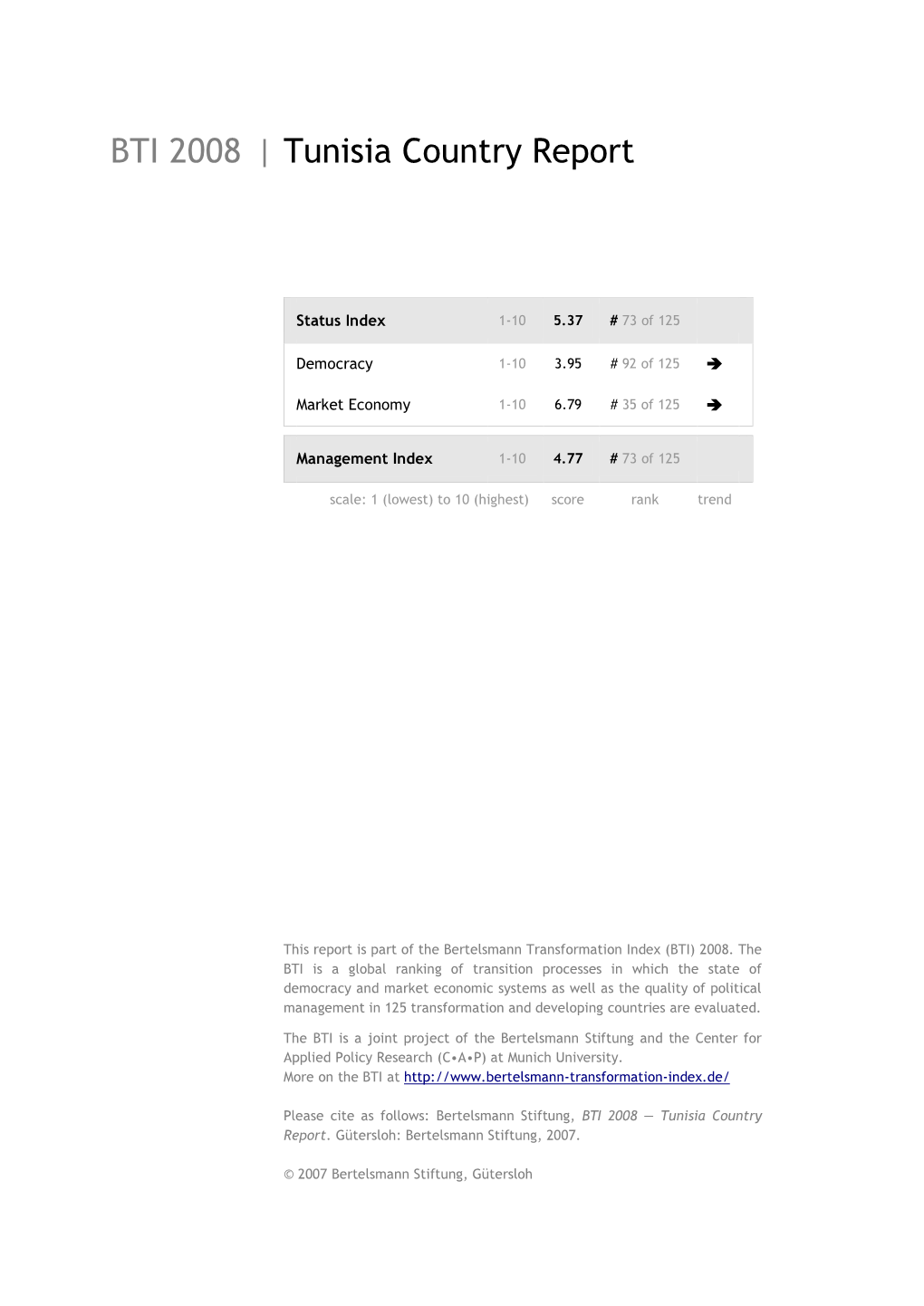

BTI 2008 | Tunisia Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamal Ben Younis Auther N

Artical Name : Vision from Within Artical Subject : Where is Tunisia Heading? Publish Date: 21/01/2018 Auther Name: Kamal Ben Younis Subject : Tunisian authorities managed to deal with the protests, which erupted in a number of cities and poor neighborhoods in the capital, after ³government announced an increase in value-added tax and social contributions in the budget.´However, the calm situation may be temporary if the authorities do not succeed in finding radical solutions to the problems, which angered youths. Those youth for seven years now have been threatening of a ³new revolution´that topples the new political elite whom they accuse of failing to achieve the main goals of their revolution which developed in January 2011.So where is Tunisia heading seven years after President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was toppled? Will the parties which triggered these new confrontations with the security forces succeed in launching what they call ³a second revolution´"Or will the opposite happen? Will the current political regime witness any substantial changes especially that it has been internationally supported for several reasons including that many western countries bet on the success of the ³Tunisian exception in transitioning towards democracy?´Separation from YouthsSome of those who oppose the government, mainly the opposition leaders of leftist, nationalist and Baathist groups that are involved in the Popular Front, which is led by Hamma Hammami and Ziad Lakhdhar, think that the increased protests against the governments, which have governed since January 2011, is proof that they cannot achieve the revolution¶s aims regarding jobs, dignity. That is because the government cannot liberate its measures from the International Monetary Fund¶s directions and from the agendas of financial lobbies that are involved in corruption, trafficking and imposing a capitalist policy. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

Political Parties and Political Development : Syria and Tunisia

POLITICAL PARTES AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT: SYRIA. AND TUNISIA by KENNETH E. KCEHN A. B. t Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas, 1966 A MASB3R»S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1963 Approved by: n-i/t-»--\. Major Processor mt. c > CONTENTS PAGE ACKMCMEDGMENTS i I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FOLITICAL PARTIES AED POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT k A. Political Parties: A Definition h, B. Political Development 7 C. Classification and Operational Aspects' 8 D. Functional Aspects 1^ III. SYBI& 32 IV. TUNISIA 45 V. CONCLUSION 62 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 75 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Tho author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Michael W. Sulei-nan for his guidance throughout this study. His practical suggestions and encouragement greatly aided this work. Special appreciation is extended to Dr. T. A. Williams and Dr. E. T. Jones for their counsel. political partes and political development syrja ake tune . In' • notion Found within most political systems today are some forms of political party or parties. Although political parties started as a Western phenomenon and reached their modem development in the West, parties today can be found in most countries throughout the world whether communist, socialist, or capitalist. The Middle East1 is no exception to this general pattern, perhaps carrying it to extremes in types and numbers of parties. TMs paper will be an attempt to compare two Middle East countries, Syria and Tunisia, with highly different political systems, and to look specifically at political parties and their relationship to the awesome problem of political development in these two countries, Although much work has been done concerning political parties and political development, it is still not known what form of party or parties will contribute most effectively to the area of political development. -

The Political Lefts in the Picture

The political lefts in the picture https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article4734 Tunisia The political lefts in the picture - IV Online magazine - 2016 - IV501 - October 2016 - Publication date: Thursday 13 October 2016 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/10 The political lefts in the picture In contrast to Egypt, left forces in Tunisia have been able to maintain continuity over several decades, even clandestinely. The main reason for this is the existence, since just after the Second World War, of a powerful trade union movement, which played a decisive role in the fight for independence and allowed left forces to partially protect themselves from the effects of repression. Some of these debates resemble those in other countries, starting with relations with the existing regimes. 1. The origins of the left Promising beginnings After the first world war, left reference points only really existed among a minority of the population of European origin. [1] This left was located in the extension of the European and above all French socialist tradition. In 1920, the majority of the Socialist Federation supported the Russian Revolution and became the section of the Communist International, favouring Tunisian independence in 1921. [2] Simultaneously, a significant number of indigenous employees began to organise in trade unions. Finding no place for themselves in the local extension of the French CGT, or in the Tunisian nationalist movement of the period, in December 1924 they founded own trade union federation, the Confédération Générale Tunisienne du Travail (CGTT - Tunisian General Confederation of Labour), including notably dockers, and rail and tram workers. -

1111~1I1 Iii~ I~

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 12 Tab Number: 33 Document Title: Report on the First Tunisian Multiparty Legislative Elections Document Date: 1989 Document Country: Tunisia IFES ID: R01910 61111~1I1 E 982 44*III~ I~ ••.·~_:s-----=~~~~=- .~ !!!!!!!national Foundation for Electoral Systems __ ~ 1620 I STREET. NW. • SUITE 611 • WASHINGTON. D.c. 20006 • 12021828-8507· FAX 12021 452-Q804 by William Zartman This report was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development Any pe~on or organizlltion is welcome to quote information from this report if it is attrlJuted to IFES. DO NOT REMOVE. FROM IFES RESOURCE CENTER! BOARD OF F. Clifton White Patricia Hurar Jdmes M. Cannon Randal C. Teague DIRECTORS Chairman Secretary Counsel Richard M. Scammon Ch.3rles Manaa John C. White Richard W. Soudrierre Vice Chairman Treasurer Robert C. Walker Director REPORT ON THE FIRST TUNISIAN MULTIPARTY LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS I. William Zartman A Introduction After a third of a century's experience in single-party elections, Tuni . were offered their first multiparty electoral choice in the general elections 0 2 April 1989. The elections were free and fair, and the results were IJrobably reported accurately._Out. of a population of abou 8 millio and a voting-age (over 18) population of about 4 million, 2.7 million, o~ 76.46%, vote~. Candidates from the ruling partY, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (ReD), averaged-;bout 1.7 million votes. All of them were elected. Although none of the 353 opposition candidates were elected, the vote effectively endowed Tunisia with a two-party system plus an unusual twist: The second "party", the Islamic Fundamentalist Nahda or Renaissance:: Party, still remains to be recognized, and its religious nature poses a serious problem to the Tunisian self-image in the current context. -

Rule of Law Quick Scan Tunisia

Rule of Law Quick Scan Tunisia The Rule of Law in Tunisia: Prospects and Challenges Rule of Law Quick Scan Tunisia Prospects and Challenges HiiL Rule of Law Quick Scan Series This document is part of HiiL’s Rule of Law Quick Scan Series. Each Quick Scan provides a brief overview of the status of rule of law in a country. November 2012 The writing of the Quick Scan was finalised in April 2012 HiiL Quick Scans | The Rule of Law in Tunisia 2 The HiiL Rule of Law Quick Scan Series is published by HiiL. Content & realisation Quick Scan on the rule of law in Tunisia: HiiL, The Hague, The Netherlands Arab Center for the Development of the Rule of Law and Integrity (ACRLI), Beirut, Libanon Editor in chief: Ronald Janse, HiiL, The Hague, The Netherlands Author: Dr. Mustapha Ben Letaief Published November 2012 Feedback, comments and suggestions: [email protected] © 2012 HiiL All reports, publications and other communication materials are subject to HiiL's Intellectual Property Policy Document, which can be found at www.hiil.org About the Author | Dr. Mustapha Ben Letaief Mustapha Ben Letaief studied law mainly in France where he got his PHD in public law. He is a professor at the university of Tunis El Manar since 1989 and the national school of administration of Tunis since 1997 where he teaches administrative law, public policies, procurement and public private partnership law, competition and regulation law. He is the head of research a center at the university of Tunis called “law and governance research unity”. -

The Tunisian Revolution of 2010-2011

PROMISES AND CHALLENGES: THE TUNISIAN REVOLUTION OF 2010-2011 The Report of the March 2011 Delegation of Attorneys to Tunisia from National Lawyers Guild (US), Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers (UK), and Mazlumder (Turkey) Published: June 2011 National Lawyers Guild · 132 Nassau St., Rm. 922 · New York, NY 10038 (212) 679-5100 · www.nlg.org Table of Contents PART I: PREFACE 1 A. Introduction 1 B. Methodology 1 C. The Revolutionary Landscape 3 PART II: OVERVIEW OF REPRESSION AND RESISTANCE IN TUNISIA 7 PART III: KEY REVOLUTIONARY ACTORS IN THE TUNISIAN REVOLUTION 14 A. Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) 14 B. Tunisian Communist Workers Party (POCT) 15 C. Hibz An‐Nahda (Nahda) 17 PART IV: SUMMARY OF MEETINGS 23 PART V: THE IMPACT OF THE WAR ON TERROR ON TUNISIA 25 A. Background: Human Rights in Tunisia before the War on Terror 25 B. The Bush Administration's War on Terror Begins 25 C. Tunisia's 2003 Anti‐Terrorism Law 27 D. Recent Developments: The General Amnesty 30 E. The Role of the United States 32 PART VI: SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 40 A. Summary and Conclusions 40 B. Recommendations 44 Table of Contents ‐ i Appendix I: Tunisia Delegation Profiles Appendix II: Summary of Delegation Meetings Table of Contents ‐ ii PART I: PREFACE A. Introduction Had you stood on any street corner in the U.S. before December 2010 and asked passersby what they knew about Tunisia, you'd likely have been met with blank stares. In Europe you would have fared a bit better; Europeans knew it as a tourist destination, but most knew as little about the nation's political system as Americans. -

Communist/Socialist Ideologies and Independence Movements in Africa

International Journal of Humanities, Art and Social Studies (IJHAS), Vol. 4, No.4, November 2019 COMMUNIST/SOCIALIST IDEOLOGIES AND INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENTS IN AFRICA Richard Adewale Elewomawu Department of History, Kogi State College of Education, Ankpa, Kogi State. Nigeria ABSTRACT It is almost impossible to separate communist/socialist ideologies from African independence movement. But Africa has been marginalised in the extant literature of communism and socialism. This accounts for the very limited study that has been done as regards the relationship between the liberation movement of African and communist/socialist ideologies. This paper did a thorough study of all the independence movements of Africa and realised that communism and socialism were unifying weapons of these liberation movements in their quest for the eradication of colonialism. Most of these African countries such as South Africa, Algeria, Tunisia, Madagascar etc had formidable Communist Parties, which took up arms to fight against the colonialists to gain independence. This paper has been able to bridge the research gap of the role of communist/socialist ideologies in the attainment of independence in most African countries. KEYWORDS Africa, Independence Movement, Communism, Socialism 1. INTRODUCTION In the discussion of communist and socialist ideologies, Africa seems to be ostracized. The spread of these ideologies and the roles they played in the world are usually discussed with little or no reference to Africa. The literature on communism and socialism do not give preference to African continent. However, the role of communist and socialist dialogue in the liberation movement of African countries cannot be overemphasized. This study finds out that these ideologies served as unifying factors and motivators for some of the major independence movements on the continent. -

Tunisia Document Date: 1993

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 12 Tab Number: 32 Document Title: Pre-Election Technical Assessment: Tunisia Document Date: 1993 Document Country: Tunisia IFES ID: R01908 ~~I~ I~~I~ ~II ~I~ F - A B A F B C A * PRE-ELECTION TECHNICAL AssESSMENT TuNISIA December 15 - December 22, 1993 Jeff FISCher Dr. Clement Henry DO NOT REMOVE FROM IFES RESOURCE CENTER! INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTORAL SYSTEMS Pre-Election Technical Assessment: TUNISIA December 15 - December 22, 1993 Jeff Fischer Dr. Clement Henry January 31, 1994 Adila R. La"idi - Program Officer, North Africa and the Near East Keith Klein - Director of Programs, Africa and the Near East This report was made possible through funding by the United States Agency for International Development ! TABLE OF CONTENTS [. I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. .. 1 r. II. INTRODUCTION' . .. 3 r: m. CONTEXT OF DEMOCRATIZATION .......................... 5 A. Geographical Context . .. 6 B. The Pace of Democratization ............................ 9 r: C. Recent Events ..................................... 11 [] IV. LAWS AND REGULATIONS ................................ 14 A. Constitution ....................................... 14 B. Electoral Law ..................................... 14 L C. Other Relevant Laws ................................. 16 L V. ELECTORAL~lNSTITUTIONS_AND.OFFICIALS ................... 19 VI. POLmCAL-PARTIES'ANDCAMPAIGNING: ..................... 21 L A. Democratic~Constitutiona1Rally :(RCD).' ....................... '. 21 B. Movement· of Socialist Democrats:(MDS),>., .......... -

Contrasting Notions of History and Collective Memory

1 2 3 4 Preface The “Transitional Justice Barometer” continues to support the process of transitional justice in Tunisia, through a research work that involves Tunisian experts from “Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center”, and international experts from the “University of York” (England) and “Impunity Watch” (Netherlands). The Barometer, jointly with its partners, has chosen to focus this third study on “memorialization” and “collective memory”, being important elements in the process of transitional justice that the Tunisian experience has not addressed yet. The study is entitled “History and Collective Memory in Tunisia : Contrasted Notions. Teaching Recent History and the Figure of Bourguiba Today.” As part of this qualitative research, interviews were conducted with 45 experts and teachers of history and civic education in the Governorates of Sousse (Center-East) and Gafsa (Saouth-West). With this third study having been carried out, the six regions of the country are now covered by the Transitional Justice Barometer project. The study places special focus on Habib Bourguiba, a pivotal figure in the modern history of Tunisia. It examines the textbooks used in the teaching of history and assesses their impact on collective memory. The study ends with a number of conclusions and recommendations that seek to contribute to the reform of the teaching of history and civic education, supposed to be one of the outputs of the transitional justice process. To conclude, the “Transitional Justice Barometer” wishes to thank all the interviewed teachers and experts for having contributed to the success of this research work. On its part, “Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center” wishes to thank its partners, the “University of York” and “Impunity Watch”, for the valuable expertise they have transferred to Tunisian researchers. -

Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (IV): Tunisia's

POPULAR PROTEST IN NORTH AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST (IV): TUNISIA’S WAY Middle East/North Africa Report N°106 – 28 April 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. BETWEEN POPULAR UPRISING AND REGIME COLLAPSE .............................. 3 A. THE UPRISING’S TRAINING EFFECTS ............................................................................................ 3 1. The provincial revolt: From the socio-economic to the political ................................................. 3 2. The UGTT’s call for insurrection ................................................................................................ 5 3. The virtual erupts into the real ..................................................................................................... 6 4. The limited role of political parties .............................................................................................. 8 B. A REGIME WITH CLAY FEET ........................................................................................................ 9 1. The RCD resignation ................................................................................................................... 9 2. From a one-party state to a predatory regime ............................................................................ 10 3. The fragmentation of the security apparatus ............................................................................. -

The Tunisian Exception Profile of a Unique Political Laboratory

The Tunisian Exception Profile of a unique political laboratory The Monographs of ResetDOC Ben Achour, Benstead, Boughanmi Fanara, Felice, Garnaoui, Hammami Hanau Santini, Nelli Feroci, Zoja edited by Federica Zoja The Monographs of Reset DOC The Monographs of ResetDOC is an editorial series published by Reset-Dialogues on Civilizations, an international association chaired by Giancarlo Bosetti. ResetDOC pro- motes dialogue, intercultural understanding, the rule of law and human rights in var- ious contexts, through the creation and dissemination of the highest quality research in human sciences by bringing together, in conferences and seminars, networks of highly esteemed academics and promising young scholars from a wide variety of back- grounds, disciplines, institutions, nationalities, cultures, and religions. The Monographs of ResetDOC offer a broad range of analyses on topical political, so- cial and cultural issues. The series includes articles published in ResetDOC’s online journal and original essays, as well as conferences and seminars proceedings. The Monographs of ResetDOC promote new insights on cultural pluralism and inter- national affairs. The Tunisian Exception Profile of a unique political laboratory Edited by Federica Zoja Reset Dialogues on Civilizations Scientific and Founding Committee Chair: José Casanova Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd (1943-2010), Katajun Amirpur, Abdullahi An-Na’im, Abdou Filali-Ansary, Giancarlo Bosetti, Massimo Campanini, Fred Dallmayr, Silvio Fagiolo (1938-2011), Maria Teresa Fumagalli Beonio Brocchieri, Nina zu Fürstenberg, Timothy Garton Ash, Anthony Giddens, Vartan Gregorian, The Monographs of ResetDOC Renzo Guolo, Hassan Hanafi, Nader Hashemi, Roman Herzog (1934-2017), Ramin Jahanbegloo, Jörg Lau, Amos Luzzatto, Avishai Margalit, Krzysztof Michalski (1948-2013), Andrea Riccardi, Olivier Roy, Publisher Reset-Dialogues on Civilizations Otto Schily, Karl von Schwarzenberg, Bassam Tibi, Roberto Toscano, Via Vincenzo Monti 15, 20123 Milan – Italy Nadia Urbinati, Umberto Veronesi (1925-2016), Michael Walzer.