The Novels and Stories of Ivan Turgenieff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2015

CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework 2015 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] NEEDLEWORK SWEET BAG OR SACHET English, third quarter of the 17th century For residents of seventeenth-century England, life was pungent. In order to combat the unpleasant odors emanating from open sewers, insufficiently bathed neighbors, and, from time to time, the bodies of plague victims, a variety of perfumed goods such as fans, handkerchiefs, gloves, and “sweet bags” were available for purchase. The tradition of offering embroidered sweet bags containing gifts of small scented objects, herbs, or money began in the mid-sixteenth century. Typically, they are about five inches square with a drawstring closure at the top and two to three covered drops at the bottom. Economical housewives could even create their own perfumed mixtures to put inside. A 1621 recipe “to make sweete bags with little cost” reads: Take the buttons of Roses dryed and watered with Rosewater three or foure times put them Muske powder of cloves Sinamon and a little mace mingle the roses and them together and putt them in little bags of Linnen with Powder. The present object has recently been identified as a rare surviving example of a large-format sweet bag, sometimes referred to as a “sachet.” Lined with blue silk taffeta, the verso of the central canvas section contains two flat slit pockets, opening on the long side, into which sprigs of herbs or sachets filled with perfumed powders could be slipped to scent a wardrobe or chest. -

Autumn 2017 Cover

Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Front cover image: John June, 1749, print, 188 x 137mm, British Museum, London, England, 1850,1109.36. The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Managing Editor Jennifer Daley Editor Alison Fairhurst Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org i The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 ISSN 2515–0995 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2017 The Association of Dress Historians Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession number: 988749854 The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer–reviewed environment. The journal is published biannually, every spring and autumn. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is distributed completely free of charge, solely for academic purposes, and not for sale or profit. The Journal of Dress History is published on an Open Access platform distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The editors of the journal encourage the cultivation of ideas for proposals. -

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College Deaccession of Clothing and Accessories from the Costume Collection

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College Deaccession of Clothing and Accessories from the Costume Collection Approved by the Hood Museum of Art Acquisitions Committee May 13, 2013 The following textiles have been deaccessioned and transferred to the Theater Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College, unless otherwise noted. Evening Gown, originally c. 1900-1908 Off-white silk faille decorated with beige and grey appliqué, embroidery, and sequins Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Morris Burrows; 180.15.23199 Reason: The ball gown was remade sometime after its original date. It lost its original shape and silhouette. Also, the fabric is very dirty around the lower edge of the skirt. Evening Dress, 1920-30 Black lace Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 177.8.22492 Reason: Because the design of the dress is rather ordinary, and there are better examples in the collection, it is likely that it will never be exhibited. Day Dress for a Large Lady, 1925-35 Blue and white crepe Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 177.8.22520 Reason: Crepe is in fair condition. Probably the dress would never be exhibited due to its large size. Day Dress with Long Sleeves and Sash, 1924-32 Red silk Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 177.8.22521AB Reason: There are multiple stains on the skirt, and the neckline is torn in the center front. Day Dress, 1925 Black and red crepe-backed satin with rows of black soutash braid on the lower section of the skirt Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 178.18.22591 Reason: The hemline edge is stained when the hem was lengthened previously. -

What's Happening At

What’s Happening at MERRY CHRISTMAS A Message from the CEO & HAPPY NEW YEAR 2020 has been a challenging year. We are Welcome to the December Feliz Navidad y Próspero Año Nuevo fortunate that so far South Australia has not edition of What’s Happening had to endure the same hardships as other gayaay gaangangindaay places in Australia and internationally. at YourPlace. Frohe Weihnachten und ein Our community has still felt the impact. gutes neues Jahr! The YourPlace Board and staff members are keenly aware of this and are eager to Joyeux Noël et bonne année ensure that we play our part in supporting Auguri di buon Natale e felice people who are doing it tough through Anno Nuovo this difficult time. Meri Kirihimete Ngā mihi mō I am hopeful that restrictions will continue te Tau Hou to ease, and that we can start to reignite some of our community engagement Καλά Χριστούγεννα και activities in the early New Year. I am very Ευτυχισμένο το Νέο Έτος much looking forward to meeting many Wesołych Świąt i szczęśliwego of you over the coming weeks and months Nowego Roku to hear your thoughts and ideas about ماعلا لولحب تاينمألا بيطأ عم YourPlace, and I am also eager to share ديدجلا with you some of the great things we are hoping to achieve into the future. Chúc Giáng Sinh An Lành. On behalf of the team at YourPlace we Chúc Mừng Năm Mới 2021! would like to wish you and your loved As the incoming CEO, I feel incredibly त्योहारों की बधाई एवं वर्ष 2021 ones a restful and happy Festive Season, privileged to be working for an organisation के लिए शुभकामनाएं! and we hope that the New Year sees that is deeply committed to providing کرابم ون لاس your home filled with laughter, love suitable and affordable housing to you and good health. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Read Book the Knitting Palette: 25 Stunning Colour Inspired Designs

THE KNITTING PALETTE: 25 STUNNING COLOUR INSPIRED DESIGNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kristin Nicholas | 176 pages | 28 Mar 2008 | DAVID & CHARLES | 9780715329184 | English | Newton Abbot, United Kingdom The Knitting Palette: 25 Stunning Colour Inspired Designs PDF Book Get the Look: Leather Ottoman-Pouf. Traditional Scandinavian style values bright, airy spaces, making light wood floors the perfect pick. Clothing portal. In the mid to end of the s, African American style changed and developed with the times. Textiles in Indonesia have played many roles for the local people. Robert Glariston, an intellectual property expert, mentioned in a fashion seminar held in LA [ which? Recycled wool coats in tow tone off white and black with recycled buttons. Spontaneous road trips and amusement parks were my favorite part of summer when I was growing up. Historians, including James Laver and Fernand Braudel , date the start of Western fashion in clothing to the middle of the 14th century , [13] [14] though they tend to rely heavily on contemporary imagery [15] and illuminated manuscripts were not common before the fourteenth century. With a unique cultural and historical background, HK designers are known for their creativity and efficiency. Perfect for wrapping yourself in for your next road trip! A recent development within fashion print media is the rise of text-based and critical magazines which aim to prove that fashion is not superficial, by creating a dialogue between fashion academia and the industry. The New Yorker. MIT Technology Review. Black activists and supporters used fashion to express their solidarity and support of this civil rights movement. To Bettie fashion means to be oneself. -

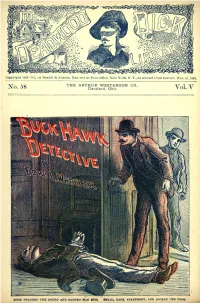

D22-00057-V05-N58-1899-03-15

8opyright 1813.3 !%~ . •>Y Beadl e & A<lams. Ent.. ·red at Po~t Ot'flce. New York , N. Y., as second class m a tter . l\ta r.15, 1899. THE ARTHUR WESTBROOK CO. No. 58 Cleveland, Ohio Vol. V DUCK DR.AOGKU THE BOUND ANO G.t.GG&ll 11.411' &>n'O SMALL. DARK. APARTKltNT, AND LOCK KD THE DOOR. hn" rlght 1883-1889, by Beadle&: Adams. Entered at Post Oll1ce, New York, N. Y., as second ClllS!!. matter. Mar. lb,~ THE• ARTHUR WESTBROOK CO. No.58 Cleveland, O hio Vol. V • Here, numerous rows •A hou90S have for yean bean converted into offices, which are occuvted Buck Hawk, Detective: hy perhaps as many di1ferent tradM and pro OR, fessions as there are rooms. Into the second story front room of one of tb0110 buildings, the gentleman ushered Turk., The Messenger Boy's Fortune. and bade him be seated, until he returned; afte: whicb be went down-stairs. BY EDWARD L WHEELER, The apartment was meagerly furnished, tbe AUTHOR OF "DEADWOOD DICK" NOVELS, ETC. floor being covered with oilcloth, and a desk, several office chairs, a few pictures on the wall CHAPTER I. forming the rem11inder of the furnitu;·e. AN ARTFUL DODGER. Having nothing else to do, Turk amused him· "CAN you furnish mB with a trusty messen self with looking at the pictures, which were of ger boy for a couple of hours-one, mind you, men whose faces were anything but ro their who is reliable in every se>nse of the word, and credit. -

Competitive Camping Phiona Stanley

Competitive camping Phiona Stanley Published April 2018 in New Philosopher, Issue 20, pp.109-111. I recently fell down the social media rabbit hole that is the Vanlife hashtag. In it, girl-next-door models pose casually with expensive coffee pots in reclaimed- wood-lined campervans in front of iconic, North American national park views. Accompanying images depict the same women in bikinis doing yoga on beaches, soulful, woodsy men hunched over guitars, and, often, an aerial drone shot of the entirety of the (young, straight, white, het, cis, educated, beautiful, rich) couple’s possessions neatly laid out around the van. These photos depict high-end wetsuits, surfboards, MacBooks, retro kitchen gear, and, always —apparently there is a Vanlife by-law about this— a southwest serape blanket. Ostensibly about minimalism and rejecting wage-slavery, Vanlife as constructed on social media is about yearning for a certain kind of high-end stuff and the financial wherewithal to roam freely. The campervan I recently converted from a former electrician’s van looks nothing like the Vanlife images. I built it myself, using YouTube instructional videos, grit and determination, sweat and tears. There are many rough edges. Its look is rather more crafty DIY and rather less Monocle magazine. And, just as my van looks different, I don’t resemble the Vanlife models: I’m twice their age and I’m not half of a young, beautiful, straight, white couple. But the differences go beyond aesthetics. My van is smaller than most campervans: I drive and park in a city and I need maneuverability rather than an apartment-like dwelling on wheels. -

1 ORIGINAL ART WORK EMBROIDERY DESIGNS EARLY 20Th C German Designs in Pencil on Tissue

1 ORIGINAL ART WORK EMBROIDERY DESIGNS EARLY 20th C German designs in pencil on tissue. FIT 2 PRINTED AND WOVEN VEST FABRICS, 19th C. In two sample books with brocades and velvets. FIT 3 JAPANESE TEXTILE SAMPLES AND STENCILS, 19th -20th C Two textile sample books and folio of stencils. Approx. 48 designs. FIT 4 ORIGINAL ART WORK FOR PRINTED COTTON DESIGNS, 19th - early 20th C Approximately twenty painted designs on paper mounted on mat board. FIT 5 PHOTO REPRODUCTIONS ON PAPER OF TEXTILE DESIGNS INCLUDING LACES, EARLY 20th C. Approximately 20 volumes or folios. FIT 6 FORTUNY FABRIC SAMPLES, 20th C Thirty Five carded samples various designs and colorways. FIT 7 FRENCH FABRIC SAMPLE BOOK, 19th C. Mostly madder dyed cottons 1820-1850. FIT 8 PRINTED COTTON FLANNEL SAMPLE BOOKS, 1930s. Two French books (unbound) in boxes. FIT. 9 HOPE SKILLMAN CO. SAMPLE BOOKS, 20th C Fabric and scrap books. FIT 10 THREE FABRIC SAMPLE BOOKS, 1920’s - 1930’s Two woven silks including ribbons and labels. One printed cotton percales. FIT 11 INTERNATIONAL TAILORING CO. FABRIC SAMPLE BOOK, 1917 - 1918. Large format book, mostly men's suit fabrics, having numerous polychrome men's fashion illustrations. (Most samples removed), overall fair, illustrations excellent. 12 LARGE LOT of LACE and EMBROIDERED FABRIC SAMPLES, 19th - 20th C. White or cream with tone on tone decoration. Fair-excellent. 13 LOT of FABRIC SAMPLES, EARLY - MID 20th C. Mostly polychrome embroidered white or cream linen, some printed. Fair-excellent. 14 TEN SILK JACQUARD FABRIC SAMPLES, 18th - 19th C. Mostly large pieces. 15 LOT of ETHNIC EMBROIDERED FABRIC SAMPLES, 20th C. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 507 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2020) The Origin and Development of the "Ordinance on Apparel System" of the Republic of China in the Context of Culture Defeng Song1,* Jie Wang1 1Northeast Electric Power University, Jilin, Jilin 132000, China *Corresponding author. Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT The promulgation and formulation of ordinances on apparel system in past dynasties are not only the factors restricting clothing culture, but also the factors promoting clothing culture. The enactment of the ordinances on apparel system of the Republic of China is the inheritance of the Chinese costume system, such as The History of "Yu Fu Zhi" ("舆服志", record of the clothing systems) and "Li Yi Zhi" ("礼仪志", record of etiquette), as well as the denouncement and continuation of the historical remnants of the previous dynasties. The ordinances on apparel system of the Republic of China emerged with the collapse of feudalism which lasts for over 2,000 years along with the fall of Qing Government. With its presence attached to the turbulent situation of the society, it was the driving force of social progress. The beginning of the apparel system of the Republic of China began with the rise of the "braid-cutting and costume changing" movements. What were cut off were not only the long braids in form, but also the feudal culture of the Qing Dynasty and what were changed were not only the tedious Manchu clothing at that time, but also the culture in a new era. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

You Are What You Wear: Clothing and American Authors of the Early 20Th Century

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2018 You Are What You Wear: Clothing and American Authors of the Early 20th Century Alyssa Q. Johnson Abilene Christian University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Alyssa Q., "You Are What You Wear: Clothing and American Authors of the Early 20th Century" (2018). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 77. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ABSTRACT Though clothes are often said to “make the man,” they are not frequently said to build a character. This thesis explores the ways in which clothing was a performative tool for those who wore it during the 1920s in America as well as for authors who wrote about this world in which they lived. This study’s theoretical framework is inspired by Judith Butler’s concept of the performative; it is also influenced by historical research into the clothing of the 1920s. Primary texts explored include F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night, Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, and Jessie Redmon Fauset’s Plum Bun: A Novel without a Moral. In each of these works, clothing is used symbolically as a way to emphasize thematic elements, but it is also used as a tool through which the author builds characters.