'Kimono' for the Western Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2015

CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework 2015 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] NEEDLEWORK SWEET BAG OR SACHET English, third quarter of the 17th century For residents of seventeenth-century England, life was pungent. In order to combat the unpleasant odors emanating from open sewers, insufficiently bathed neighbors, and, from time to time, the bodies of plague victims, a variety of perfumed goods such as fans, handkerchiefs, gloves, and “sweet bags” were available for purchase. The tradition of offering embroidered sweet bags containing gifts of small scented objects, herbs, or money began in the mid-sixteenth century. Typically, they are about five inches square with a drawstring closure at the top and two to three covered drops at the bottom. Economical housewives could even create their own perfumed mixtures to put inside. A 1621 recipe “to make sweete bags with little cost” reads: Take the buttons of Roses dryed and watered with Rosewater three or foure times put them Muske powder of cloves Sinamon and a little mace mingle the roses and them together and putt them in little bags of Linnen with Powder. The present object has recently been identified as a rare surviving example of a large-format sweet bag, sometimes referred to as a “sachet.” Lined with blue silk taffeta, the verso of the central canvas section contains two flat slit pockets, opening on the long side, into which sprigs of herbs or sachets filled with perfumed powders could be slipped to scent a wardrobe or chest. -

Typical Japanese Souvenirs Are a Kimono Or Yukata (Light, Cotton

JAPAN K N O W B E F O R E Y O U G O PASSPORT & VISA IMMUNIZATIONS All American and While no immunizations Canadian citizens must are required, you should have a passport which is consult your medical valid for at least 3 months provider for the most after your return date. No current advice. visa is required for stays See Travelers Handbook for up to 90 days. more information. ELECTRICITY TIME ZONE Electricity in Japan is 100 Japan is 13 hours ahead of volts AC, close to the U.S., Eastern Standard Time in our which is 120 volts. A voltage summer. Japan does not converter and a plug observe Daylight Saving adapter are NOT required. Time and the country uses Reduced power and total one time zone. blackouts may occur sometimes. SOUVENIRS Typical Japanese souvenirs CURRENCY are a Kimono or Yukata (light, The Official currency cotton summer Kimono), of Japan is the Yen (typically Geta (traditional footwear), in banknotes of 1,000, 5,000, hand fans, Wagasa and 10,000). Although cash (traditional umbrella), paper is the preferred method of lanterns, and Ukiyo-e prints. payment, credit cards are We do not recommend accepted at hotels and buying knives or other restaurants. Airports are weapons as they can cause best for exchanging massive delays at airports. currency. WATER WiFi The tap water is treated WiFi is readily available and is safe to drink. There at the hotels and often are no issues with washing on the high speed trains and brushing your teeth in and railways. -

Autumn 2017 Cover

Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Front cover image: John June, 1749, print, 188 x 137mm, British Museum, London, England, 1850,1109.36. The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Managing Editor Jennifer Daley Editor Alison Fairhurst Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org i The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 ISSN 2515–0995 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2017 The Association of Dress Historians Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession number: 988749854 The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer–reviewed environment. The journal is published biannually, every spring and autumn. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is distributed completely free of charge, solely for academic purposes, and not for sale or profit. The Journal of Dress History is published on an Open Access platform distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The editors of the journal encourage the cultivation of ideas for proposals. -

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College Deaccession of Clothing and Accessories from the Costume Collection

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College Deaccession of Clothing and Accessories from the Costume Collection Approved by the Hood Museum of Art Acquisitions Committee May 13, 2013 The following textiles have been deaccessioned and transferred to the Theater Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College, unless otherwise noted. Evening Gown, originally c. 1900-1908 Off-white silk faille decorated with beige and grey appliqué, embroidery, and sequins Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Morris Burrows; 180.15.23199 Reason: The ball gown was remade sometime after its original date. It lost its original shape and silhouette. Also, the fabric is very dirty around the lower edge of the skirt. Evening Dress, 1920-30 Black lace Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 177.8.22492 Reason: Because the design of the dress is rather ordinary, and there are better examples in the collection, it is likely that it will never be exhibited. Day Dress for a Large Lady, 1925-35 Blue and white crepe Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 177.8.22520 Reason: Crepe is in fair condition. Probably the dress would never be exhibited due to its large size. Day Dress with Long Sleeves and Sash, 1924-32 Red silk Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 177.8.22521AB Reason: There are multiple stains on the skirt, and the neckline is torn in the center front. Day Dress, 1925 Black and red crepe-backed satin with rows of black soutash braid on the lower section of the skirt Gift of the Drama Department Costume Shop, Dartmouth College; 178.18.22591 Reason: The hemline edge is stained when the hem was lengthened previously. -

What's Happening At

What’s Happening at MERRY CHRISTMAS A Message from the CEO & HAPPY NEW YEAR 2020 has been a challenging year. We are Welcome to the December Feliz Navidad y Próspero Año Nuevo fortunate that so far South Australia has not edition of What’s Happening had to endure the same hardships as other gayaay gaangangindaay places in Australia and internationally. at YourPlace. Frohe Weihnachten und ein Our community has still felt the impact. gutes neues Jahr! The YourPlace Board and staff members are keenly aware of this and are eager to Joyeux Noël et bonne année ensure that we play our part in supporting Auguri di buon Natale e felice people who are doing it tough through Anno Nuovo this difficult time. Meri Kirihimete Ngā mihi mō I am hopeful that restrictions will continue te Tau Hou to ease, and that we can start to reignite some of our community engagement Καλά Χριστούγεννα και activities in the early New Year. I am very Ευτυχισμένο το Νέο Έτος much looking forward to meeting many Wesołych Świąt i szczęśliwego of you over the coming weeks and months Nowego Roku to hear your thoughts and ideas about ماعلا لولحب تاينمألا بيطأ عم YourPlace, and I am also eager to share ديدجلا with you some of the great things we are hoping to achieve into the future. Chúc Giáng Sinh An Lành. On behalf of the team at YourPlace we Chúc Mừng Năm Mới 2021! would like to wish you and your loved As the incoming CEO, I feel incredibly त्योहारों की बधाई एवं वर्ष 2021 ones a restful and happy Festive Season, privileged to be working for an organisation के लिए शुभकामनाएं! and we hope that the New Year sees that is deeply committed to providing کرابم ون لاس your home filled with laughter, love suitable and affordable housing to you and good health. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................ -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Read Book the Knitting Palette: 25 Stunning Colour Inspired Designs

THE KNITTING PALETTE: 25 STUNNING COLOUR INSPIRED DESIGNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kristin Nicholas | 176 pages | 28 Mar 2008 | DAVID & CHARLES | 9780715329184 | English | Newton Abbot, United Kingdom The Knitting Palette: 25 Stunning Colour Inspired Designs PDF Book Get the Look: Leather Ottoman-Pouf. Traditional Scandinavian style values bright, airy spaces, making light wood floors the perfect pick. Clothing portal. In the mid to end of the s, African American style changed and developed with the times. Textiles in Indonesia have played many roles for the local people. Robert Glariston, an intellectual property expert, mentioned in a fashion seminar held in LA [ which? Recycled wool coats in tow tone off white and black with recycled buttons. Spontaneous road trips and amusement parks were my favorite part of summer when I was growing up. Historians, including James Laver and Fernand Braudel , date the start of Western fashion in clothing to the middle of the 14th century , [13] [14] though they tend to rely heavily on contemporary imagery [15] and illuminated manuscripts were not common before the fourteenth century. With a unique cultural and historical background, HK designers are known for their creativity and efficiency. Perfect for wrapping yourself in for your next road trip! A recent development within fashion print media is the rise of text-based and critical magazines which aim to prove that fashion is not superficial, by creating a dialogue between fashion academia and the industry. The New Yorker. MIT Technology Review. Black activists and supporters used fashion to express their solidarity and support of this civil rights movement. To Bettie fashion means to be oneself. -

Culver L71ke M71ximkugkee

jn p rriIT T ' ^ c o r d ers O f f i c H*yO$ J ___ a _ CULVER L71KE M71XIMKUGKEE. V OL. IV . C U L V E R , IN D IA N A , T H U R SD A Y , OCT O BER 25, 1906. NO. 26 9 WIFE SHOT PERTAINING 1— m CULVER ACADEMY BY HUSBAND TO PEOPLE VVA1ERWOIRKS PLANS Latest News and Gossip of the Big School Domestic Infelicity in a Farmer's Brief Mention of Culverites and Specifications Ready for the New Culver Plant Family Results in Crime Visitors in Town. ---------- :--- ----- _-- -— --- -— ----- -- r r r ^ —------- Maro thc magician last Wednes Ohio, and make that place his head Following is an abstract of the 4-inch branches. The valves are day night proved the most satis quarters in the future. Captain details of the plans of the water to be of bronze. THE VICTIM WILL RECOVER PEOPLE WHO COME AND GO factory entertainer of the kind Adams, when iu the service, was works b ) far as they are of general FIRE EQUIPMENT. which the academy has had for commander of a troop in the I cav- interest: The contracting company is to THE PUMPING STATION*. furnish 500 feet of seamless woven years. To the delight of everybody, alry to which he had risen from Husband Attempts Suicide but Gathered From Many Sources for The building, 40x24, 10 feet to rubber-lined 24-inch hose, guaran including the victims, he pulled the ranks. He enlisted during the Fails of his Purpose Readers of The Citizen. -

E F Ii K L Mn N O

Xpace Cultural Centre: Volume 5 Volume Centre: Cultural Xpace b h a f rr h c w e gg q 1 2 3 4 5 tt d ii j u k + E 6 7 8 9 0 n o w - mn op v l Xpace x Volume Issue 5 y v S z v Xpace Xpace Culture Centre is a membership driv- en artist-run centre supported by the OCAD Student Union and dedicated to providing emerging and student artists and design- ers with the opportunity to showcase their work in a professional setting. We program contemporary practices that respond to the interests and needs of our membership. As we program with shorter timelines this allows for us to respond to contemporary issues in the theory and aesthetics, keeping an up to the minute response to what is going on directly in our community. Volume Volume is Xpace Cultural Centre’s annual anthology of exhibition essays, interviews and support material. Volume acts as a snap shot of the programming that hap- pens every year at Xpace across our many exhibition spaces: our Main Space, Window Space, Project Space, and External Space. The essays included here demonstrate the breadth of exhibitions and artists that help to contribute to Xpace’s place as a vibrant part of Toronto and OCAD University’s arts community. This publication gathers togeth- er documentation covering programming from August 2013 - July 2014. t Co n Main Space Window Space Storied Telling 5 Don’t Go 50 Mystery Machine 10 Observations 54 Betrayal of the 14 Arrangements 57 Proper Medium Frank 60 Provisions 21 Chalk Form Census 64 Posts and Pillars 25 Live and Active Mories 68 Fado:11:45pm 32 Long Live -

03 Oct 2019 (Jil. 63, No. 20, TMA No

M A L A Y S I A Warta Kerajaan S E R I P A D U K A B A G I N D A DITERBITKAN DENGAN KUASA HIS MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Jil. 63 TAMBAHAN No. 20 3hb Oktober 2019 TMA No. 37 No. TMA 142. AKTA CAP DAGANGAN 1976 (Akta 175) PENGIKLANAN PERMOHONAN UNTUK MENDAFTARKAN CAP DAGANGAN Menurut seksyen 27 Akta Cap Dagangan 1976, permohonan-permohonan untuk mendaftarkan cap dagangan yang berikut telah disetuju terima dan adalah dengan ini diiklankan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan disetuju terima dengan tertakluk kepada apa-apa syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan, syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan tersebut hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) Akta diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2) Akta itu, perkataan-perkataan “Permohonan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) yang diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2)” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan itu. Jika keizinan bertulis kepada pendaftaran yang dicadangkan daripada tuanpunya berdaftar cap dagangan yang lain atau daripada pemohon yang lain telah diserahkan, perkataan-perkataan “Dengan Keizinan” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan, menurut peraturan 33(3). WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN 6558 [3hb Okt. 2019 3hb Okt. 2019] PB Notis bangkangan terhadap sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan suatu cap dagangan boleh diserahkan, melainkan jika dilanjutkan atas budi bicara Pendaftar, dalam tempoh dua bulan dari tarikh Warta ini, menggunakan Borang CD 7 berserta fi yang ditetapkan. TRADE MARKS ACT 1976 (Act 175) ADVERTISEMENT OF APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS Pursuant to section 27 of the Trade Marks Act 1976, the following applications for registration of trade marks have been accepted and are hereby advertised. -

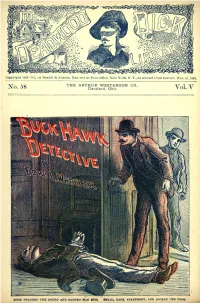

D22-00057-V05-N58-1899-03-15

8opyright 1813.3 !%~ . •>Y Beadl e & A<lams. Ent.. ·red at Po~t Ot'flce. New York , N. Y., as second class m a tter . l\ta r.15, 1899. THE ARTHUR WESTBROOK CO. No. 58 Cleveland, Ohio Vol. V DUCK DR.AOGKU THE BOUND ANO G.t.GG&ll 11.411' &>n'O SMALL. DARK. APARTKltNT, AND LOCK KD THE DOOR. hn" rlght 1883-1889, by Beadle&: Adams. Entered at Post Oll1ce, New York, N. Y., as second ClllS!!. matter. Mar. lb,~ THE• ARTHUR WESTBROOK CO. No.58 Cleveland, O hio Vol. V • Here, numerous rows •A hou90S have for yean bean converted into offices, which are occuvted Buck Hawk, Detective: hy perhaps as many di1ferent tradM and pro OR, fessions as there are rooms. Into the second story front room of one of tb0110 buildings, the gentleman ushered Turk., The Messenger Boy's Fortune. and bade him be seated, until he returned; afte: whicb be went down-stairs. BY EDWARD L WHEELER, The apartment was meagerly furnished, tbe AUTHOR OF "DEADWOOD DICK" NOVELS, ETC. floor being covered with oilcloth, and a desk, several office chairs, a few pictures on the wall CHAPTER I. forming the rem11inder of the furnitu;·e. AN ARTFUL DODGER. Having nothing else to do, Turk amused him· "CAN you furnish mB with a trusty messen self with looking at the pictures, which were of ger boy for a couple of hours-one, mind you, men whose faces were anything but ro their who is reliable in every se>nse of the word, and credit.