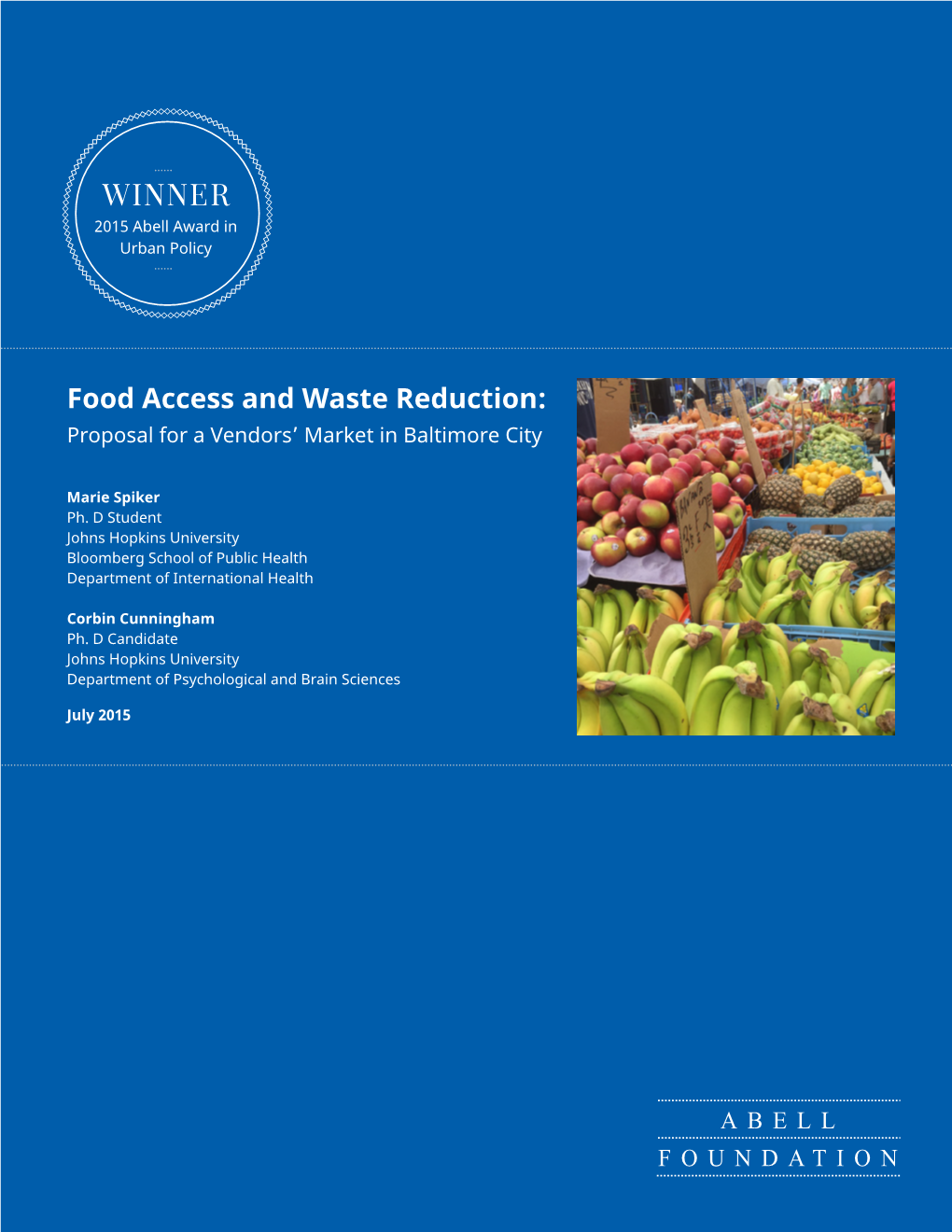

Proposal for a Vendors' Market in Baltimore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposal for Public Food Market Developer & Operator Parcel 7

PROPOSAL FOR PUBLIC FOOD MARKET DEVELOPER & OPERATOR SUBMITTED BY PARCEL 7 BOSTON, MA — COMPONENT I BOSTON PUBLIC MARKET ASSOCIATION FRIDAY MARCH 2, 2012 PARCEL 7 BOSTON, MA — COMPONENT I | BOSTON PUBLIC MARKET ASSOCIATION i BOSTON PUBLIC MARKET BOARD MEMBERS Dear Friends, BOSTON Dear Commissioner Soares, PUBLIC Donald Wiest, Esq. Janet Christensen The New Year has brought exciting news -- a site has been selected for the home of the Boston Public Market! MARKET Jeff Cole Two and a half centuries ago, downtown Boston featured a year-round marketplace; Faneuil Hall, built by Peter Fa- Tom Davis neuilThe Commonwealth in 1742 as a gift of to Massachusetts the city. Bustling has and chosen chockablock an ideal withspace butchers, at the State-owned fishmongers, “Parcel merchants, 7” building, and farmers, which Chris Douglass Faneuil Hall became a civic institution where some of the country’s greatest orators, including George Washington, Roberta Dowling, CCP is currently vacant. This site, which fronts on the new Rose F. Kennedy Greenway, is perfectly situated between BOARDBOARD MEMBERSMEMBERS Marlo Fogelman,Dear Friends, Esq. Samuelthe Financial Adams, District and Susanand North B. Anthony, Station. spoke. The building Trade flourished,contains 325 and public a spacious parking new spaces, adjunct, and Quincy features Market, direct was Jim Friedman, Esq. erected in the early 1800s. The complex remained vital well into the 20th century, before falling into disrepair in Donald Wiest, Esq. access to the MBTA’s Haymarket Stations. Construction on the new Public Market will start before year’s end. Donald Wiest, Esq. Doug Gillespie Janet Christensen The New Year has thebrought 1950s exciting as food news buying -- a habitssite has changed. -

Boston Market District Feasibility Study

Boston Market District Feasibility Study PROJECT FOR PUBLIC SPACES 3 Boston Market District Feasibility Study January 2009 SUBMITTED TO: THE BOSTON REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY SUBMITTED BY: PROJECT FOR PUBLIC SPACES 4 BOSTON REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY PROJECT FOR PUBLIC SPACES 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 8 THE BOSTON MARKET DISTRICT 13 HAYMARKET 21 ADVANCING THE MARKET DISTRICT 28 CONCEPTS FOR OUTDOOR MARKET SITES & Uses 42 PARCEL 9 CONSTRUCTION & MITIGATION PLAN 47 CONCLUSION & NEXT STEPs 48 APPENDIX 49 6 BOSTON REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An improved and expanded market district in worked on, and its geographic reach exceeds the area of Boston’s historic downtown mar- any we have seen. Its annual sales volume ap- ketplace has the potential to be not only a suc- pears to be equivalent to that of an average cessful enterprise but an iconic place within supermarket. In addition to the essential ser- the city. Full-fledged market districts are the vice it brings to its customers and to the liveli- most highly evolved form of public markets. hood it provides its vendors, its social charac- They function as synergistic economic zones ter and atmosphere are Boston attractions in in which open air markets, specialty food their own right. At the same time, Haymarket stores, and market halls reinforce each other’s presents issues of trash management, limited customer base and their economic dynamism cold and dry storage, and oversight by its man- attracts related businesses. A Boston market agement association and the City of Boston. district market district would increase the range of healthy food available to its residents, The addition of one or more market halls stimulate its economy, and enliven its culture. -

An Implementation Plan for a Public Market in Boston

An Implementation Plan for a Public Market in Boston May 2011 Submitted to: Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources Submitted by: Project for Public Spaces 700 Broadway, 4th Floor New York, NY 10003 May 2011 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 Consumer Demand 10 Vendor and Product Availability 16 Public Market Design, Merchandising and Access 24 Market Oversight and Management Structure 36 Operator Capabilities 42 Start Up Financial Requirements and Sources 46 Start Up Operation Requirement and Procedures 52 Ongoing Operational Costs 58 Conclusion 64 2 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Boston has a long history of public markets – at one time the city boasted a series of markets to serve its citizenry and visitors. As in most cities, Boston’s indoor public markets fell victim to ‘modernization’ and they all closed, with the exception of the revamped physical structures of Quincy Market and Faneuil Hall which were converted to ‘festival markets’ having little connection to Massachusetts’s producers, farms and fisheries. As the tradition of the public market makes a well-deserved reappearance into the everyday life of American cities, Boston – with its burgeoning popularity of outdoor farmers markets - is well positioned to be the next great market success story. Moreover, a new public market has the potential to strengthen Massachusetts’s agricultural economic base by providing farmers, fisheries and producers of value added products a new and significant outlet for their products. The proposed market also has the potential to save small family farms from going out of business, thus strengthening the communities from which these farms and businesses are based. -

Restaurants, Retail Shops, Cafes, Design Pushcarts, Street Performers and Food Colonnade Pam Rogers Design Merchants on the Property

FANEUIL HALL MARKETPLACE NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE April 2018 - April 2019 Vol. 8 FaneuilHallMarketplace.com ENGINEERED TO BLOW YOUR MIND Visit us in the rotunda at Faneuil Hall Marketplace LOVEPOP.COM FANEUIL HALL MARKETPLACE NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE Volume 8, Spring 2018 /Spring 2019 Publisher Emeritus Boston Starts Here Carol Troxell As “America’s First Open Marketplace,” Faneuil Hall Editor/Advertising Director Marketplace is the first stop for visitors coming to Ed Hurley Boston – as well as a favorite stop for locals – who enjoy the many restaurants, retail shops, cafes, Design pushcarts, street performers and food colonnade Pam Rogers Design merchants on the property. Editorial Ann Murphy Conveniently located in the heart of downtown Marissa Sullivan Boston, Faneuil Hall Marketplace is the cornerstone of Boston’s Market District, which also includes Production Boston Public Market, the Haymarket Pushcarts, the Christina Grise Rose Kennedy Greenway and several restaurants, Emma Curran taverns and retail outlets. Photography David Sarnevitz The District borders the Waterfront, the North End, the Financial District and Government Center. It is Management Office a well-traveled part of Boston’s “Freedom Trail.” General Manager Stay In Touch Joe O’Malley FaneuilHallMarketplace.com 617-523-1300 FaneuilHallMarketplaceBoston.com Retail & Specialty Leasing Marketplace Hours Whitney Gallivan Monday – Thursday 10 am – 9 pm [email protected] 10 am – 7 pm (Winter) Office Leasing Friday & Saturday: 10 am – 9 pm Robert Le Clair Sunday: 11 am – 7 pm [email protected] -

Freedom Trail Foundation

Bringing History to Life! 2018 ® Official Brochure Old Corner Bookstore - Celebrating 300 Years Publication produced by the: Freedom Trail Foundation 617-357-8300 • TheFreedomTrail.org and William Francis Galvin • Secretary of the Commonwealth Walk the Freedom Trail® through history! Experience more than 250 years of history along the Freedom Trail – Boston’s iconic 2.5 mile red line leading to 16 nationally significant historic sites, each one an authentic treasure. The Freedom Trail is a unique collection of museums, churches, meeting houses, burying grounds, parks, a ship, and historic markers that tell the story of the American Revolution and beyond. Learn about the people who lived here, their courage, and what they risked striving for victory and freedom. Walk Into History® on the Freedom Trail with 18th-century costumed Freedom Trail Players®, a Hear History: Audio Guide, or at your own pace. Step INSIDE the places where the American Revolution was launched, from pews and pulpits, private homes and public offices, with fiery speeches and midnight rides all in a vibrant, sophisticated, and modern city. The Freedom Trail is Boston’s indoor/outdoor history experience. For more information about Freedom Trail sites, tours, and events, or to make a donation, visit the Freedom Trail Foundation website at TheFreedomTrail.org or call 617-357-8300. Welcome to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth We hope you leave plenty of time to explore our history – especially on foot – as you travel the Freedom Trail from the magnificent Massachusetts State House to the Bunker Hill Monument. There’s a proud story in every step. -

East Boston EMS Coverage Supersedes: 01-26-97 Effective: 04-12-04

East Boston EMS Coverage Supersedes: 01-26-97 Effective: 04-12-04 The fact that the neighborhood of East Boston is physically separated from Boston proper poses some unique challenges to Boston EMS in our effort to provide the highest level of prehospital care for all residents and visitors of our city. 1. Keeping in mind the relative limited accessibility of East Boston, the Dispatch Operations Supervisor (or above) may authorize Ambulance 7, the primary BLS unit normally assigned to East Boston, to be reposted to the “Boston Side” to enhance system wide coverage. Given the ongoing construction and associated traffic pattern reconfigurations associated with the Central Artery and Tunnel (“Big Dig”) project, developing a standard set of conditions to guide this decision is impractical. Like all other unit deployment decisions, factors such as call volume, unit availability, and access / egress options should be taken into account. 1.1. After clearing a response or other assignment on the “Boston side”, Ambulance 7 may be used for a response on the Boston side without prior supervisor approval if their response time to the scene would be less than another BLS unit. 2. Whenever Ambulance 7 is unavailable for a response, another BLS unit should be reposted for East Boston coverage whenever possible. 2.1. Ambulance 8, the designated zone impact unit for Haymarket Square / East Boston, should normally repost to the East Boston side of the Callahan Tunnel unless they are unavailable or otherwise re-posted (e.g.: Charlestown 23:00---01:45). 2.2. When both A7 and A8 are unavailable, an available “extra” BLS unit (A-30, A-31 if in service) should be reposted to the East Boston side of the Callahan tunnel for East Boston coverage. -

Faneuil Hall Marketplace Neighborhood Guide

See Our Ad On Page 17. FANEUIL HALL MARKETPLACE NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE April 2019 – April 2020 Vol. 9 FaneuilHallMarketplace.com Original Merchant SHUCKING SINCE 1976 Oysters, Lobster Rolls, Chowder-Bisque, Clams, Mussels, Beer, Wine and More! Food Hall – Quincy Market Building Faneuil Hall Marketplace 3 FANEUIL HALL MARKETPLACE NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE Volume 9, Spring 2019 /Spring 2020 Publisher Emeritus Carol Troxell Welcome To Boston Editor/Advertising As “America’s First Open Marketplace,” Faneuil Hall Ed Hurley Marketplace is the first stop for visitors coming to Design Boston. The city is one of the most historic places Pam Rogers Design in the U.S. As the birthplace of the American Editorial Revolution, Boston holds a vast appeal to tourists Ann Murphy from both near and far for many different reasons. Marissa Sullivan Known as the “Cradle of Liberty,” it is here where Production several significant events took place to help shape Christina Grise our nation. Furthermore, Boston is also a sports Rita Juliano town, a college town, a cultural center and a Tori Silva maritime mecca. Photography Boston’s unique character and charm can be Chris Barajas experienced in all corners of the city and is best Erin LaVigueur seen on foot. It is one of the most walkable cities in Kristof Torok the world. Management Office Stay In Touch General Manager FaneuilHallMarketplace.com Joe O’Malley FaneuilHallMarketplaceBoston.com 617-523-1300 @faneuilhallmarketplace Public Realm/Outdoor Programming @faneuilhall Holly Masek @faneuilhall [email protected] -

Park Use Guidelines for Public Programming, Special Events and General Use

185 Kneeland Street Boston, MA 02111 617.292.0020 Rose Kennedy Greenway Park Use Guidelines for Public Programming, Special Events and General Use Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy, Inc. Adopted: June 2010; Revised December 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. BACKGROUND ON THE ROSE FITZGERALD KENNEDY GREENWAY CONSERVANCY, INC. II. PUBLIC USE AND ENJOYMENT A. DEFINITION OF GREENWAY PARK PROPERTY B. OPEN HOURS AND PARK REGULATIONS; EMERGENCY CONTACT III. PUBLIC PROGRAMS AND EVENTS: GUIDELINES AND APPLICATION PROCESS A. PROGRAMMING VISION AND PRINCIPLES B. APPLICATION PROCESS - RESERVATIONS, PERMITS AND EVENT MANAGEMENT COSTS C. EVENT POLICIES IV. APPENDIX A: MAPS OF THE ROSE KENNEDY GREENWAY PARKS V. APPENDIX B: CURRENT FEE STRUCTURE -2- I. BACKGROUND ON THE ROSE FITZGERALD KENNEDY GREENWAY CONSERVANCY, INC. The Conservancy has sole responsibility for managing all aspects of the Rose Kennedy Greenway, including horticulture, programming, public art, maintenance, and capital improvements. We envision a vibrant, inclusive, and evolving gathering place that offers ● healthy green space, ● fun, engaging, and thought-provoking experiences, and ● a testing ground for new ideas. We pursue our mission through ● park care that sustains year-round beauty, ensures safety, and models environmental stewardship; ● robust programming that showcases and supports the ingenuity and breadth of our community; and ● temporary exhibitions of contemporary public art that facilitate artistic experimentation and speak to our current moment; raising the standard of excellence for urban park management. The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), which owns the land that comprises The Greenway, has entered into a lease agreement with the Conservancy for the management, maintenance and operation of The Greenway (the MassDOT Lease), in accordance with Chapter 306 of the Acts of 2008, as amended by Chapter 242 of the Acts of 2012 (the Enabling Act). -

Haymarket Hotel Moves Forward

1 MAY 3, 2018 PUBLISHED EVERY OTHER THURSDAY BOOK YOUR POST IT Call Your Advertising Rep TT HEHE NN OROR TT HH EE NN DD (781)485-0588 EMAIL: [email protected] WWW.NORTHENDREGIONALREVIEW.COM [email protected] RREGIOEGIONNALAL RREVIEWEVIEW ON THE GREENWAY Crime is down Area A-1 sees 8-percent drop in Part One crime so far in ‘18 By Dan Murphy in 2017. Non-domestic aggravated Area A-1 has seen an 8-per- assaults, on the other hand, cent decrease in violent and were down slightly as the num- property crime to date in 2018, ber of incidents fell to 67 from compared to last year. 69 last year. According to Boston Police, Commercial burglaries were 602 incidents of Part One crime up around 38 percent as the were reported between Jan. 1 number of incidents climbed to and April 8 of this year in the 18 from 13 in 2017, while res- area, which includes Beacon idential burglaries were down Hill, Chinatown Downtown nearly 41 percent as the number and the North End, as opposed fell to 13 from 22 in 2017. The number of other burglar- to 655 during the same time- ies dropped to one incident from frame in 2017. two last year. No homicides were reported Larcenies from motor vehi- either this year or last while cles were down about 20 per- the rate of rapes and attempted cent as the number of incidents rapes remained the same with fell to 94 from 118 in 2017. six incidents a piece in 2017 and Other larcenies saw a nearly 2018. -

Central Artery Parcel 9 Haymarket Parcel 9

BOSTON REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN PLANNED DEVELOPMENT AREA N NO. __ Central Artery Parcel 9 Haymarket Parcel 9 Investor LLC ______________, 2016 Development Plan: In accordance with Sections 3-1A, 49-5, 49-11, 45-9 through 45- 13 and Section 80C of the Boston Zoning Code (the “Code”), this Development Plan for the Parcel 9 Project, Planned Development Area No. __ (the “Development Plan”), sets forth information on the proposed development (the “Project”) of the site known as MassDOT Central Artery Parcel 9, including the proposed location and appearance of structures, open spaces and landscaping, proposed uses, densities, proposed traffic circulation, parking and loading facilities, access to public transportation and proposed dimensions of structures. This Development Plan sets forth the zoning for the Project. The Project has undergone review through Article 80B of the Code. An Expanded Project Notification Form (“PNF”) for the Project was filed with the Boston Redevelopment Authority (the “BRA”) on October 14, 2014. Based upon that process and approval of this Development Plan, final plans and specifications for the Project will be submitted to the BRA pursuant to Section 3-1A and Section 80C of the Code for final design review approval and certification as to consistency with this Development Plan. This Development Plan consists of 5 pages of text and Exhibits A, B and C. All references to this Development Plan contained herein shall pertain only to such 5 pages and Exhibits A, B and C. Exhibit C and the Project described herein are subject to final design, environmental and other development review by the BRA and other governmental agencies and authorities, and the Project as described herein may evolve in the course of such review. -

BIG DIG Diaframmi Boston (MA), USA Slurry Walls Jet Grouting Jet Grouting

C M Y CM MY CY CMY K worldwide leader in the foundation engineering field REFERENZA TECNICA - TECHNICAL REFERENCE Central Artery BIG DIG Diaframmi Boston (MA), USA Slurry Walls Jet Grouting Jet Grouting Cliente : The Commonwealth of Massachussetts Owner : Highway Dept. Ten Park Plaza - Boston MA Contrattista principale : Main Contractor : TREVIICOS Durata dei lavori : Duration of works: 1997 - 2000 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Introduzione Introduction In the 1930s, city planners in Boston, pressured to make their downtown more easily accessible by automobile, proposed the construction of an elevated frecvay through the center of the city. Thirty years later, the aptly named Central Artery was fully reallzed and carried about 75,000 vehicles a day between the Charles River and the southern side of the city. By the 1980s, however, the Central Artery had already become obsolete, with more than 150,000 vehicles traversing the six- lane thoroughfare each day. Faced with dire traffic predictions for the near future, Boston’s city planners went back to the drawing board. This time, instead of a highway in the sky, as the artery was sometimes called, the planners envisioned a vast system of tunnels beneath the city-a system so A B C Contract: A Contract: C09 A4 C C15 A1 Owner: Owner: J.F.White - Slattery - Interbeton - Perini J.V. J.F. White - Perini - Slattery Works: Works: Slurry walls-Jet grouting-Soilmixing for the 139-190 Slurry walls for excavation support of the Central interchange Artery Tunnel between Chardon and North Street Contract: Contract: D C17 A9 B C09 A7 Owner: Owner: Moder Continental - Obayashi J.V. -

Public Market Precedent Report Focuses S M Oi Nes Ri Ver on Understanding Key Elements That Make Dr Fleur Public Markets Successful Around the Nation

PUBLIC MARKET REPORT ISU CDL: AGRICULTURAL URBANISM TOOLKIT 10 I-235 W MLK PKWY W MLK 5 9 6 Grand Ave Walnut Ave Court Ave 1 4 E 6th St 2 E 4th St 3rd St 5th St 7th St 11 9th St MLK PKWY Project Summary 3 8 E 14th St E 14th De The Public Market Precedent Report focuses s M oi nes Ri ver on understanding key elements that make Dr Fleur public markets successful around the nation. 7 LEGEND City Outline This research will be utilized in the design Major Waterway Lake City Park Interstate process of a public market and urban City Streets City Bridges 1 Cowles Common 2 Western Gateway Park farm in Des Moines, Iowa. Key areas of 3 DSM Social Club 4 Court Avenue Stip 5 Iowa Events Center 6 ‘Gate Way Market’ interest include education, farmer and food 7 Gray’s Lake 8 Principal Park 9 State Capitol Complex 10 Botanic Gardens entrepreneur vendor space, farming area, 11 Principal Riverwalk outreach, education, and sustainability. Partners:: ISU Community Design Lab, Des Moines Social Club (Zach Mannheimer), Central Iowa Shelter Services (Tony Timm), ISU This precedent study is the frst of several Extension and Outreach (Alice Topaloff and David Pattillo), Viva that will be conducted. Subsequently, East Bank (Beth Hicks), Des Moines Social Club (Cyndi Pederson), City of Des Moines Real Estate (David DeForest-Colvig, Amber an urban farm study will be completed Lynch, Erin Olson-Douglas), Whole Foods (Greg Van Den Berghe), ISU Value Added Agriculture (Ray Hansen), Lutheran Services of to understand the feasibility and existing Iowa (Hilary Burbank), Cherry Glen Learning Farm (Ray Meylor), Autumns Gardens (LewisJoe Rathman and George McCloskey), practices for urban farms utilizing rooftop Eat Greater Des Moines (Aubrey Alvarez and Linda Gobberdiel), Greater Des Moines Partnership (Mike Colwell and Tim Leach), gardening, vertical farming, aquaponics Des Moines Farmers Market (Kelly Foss), Des Moines Arts (Siobhan and hydroponic farming.