Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arguelles Climbs to Victory In2.70 'Mech Everest'

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, 62°F (17°C) Tonight: Cloudy, misty, 52°F (11°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Scattered rain, 63°F (17°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 119, Number 25 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, May 7, 1999 Arguelles Climbs to Victory In 2.70 'Mech Everest' Contest By Karen E. Robinson and lubricant. will travel to Japan next year to ,SS!)( '1.1fr: .vOl'S UHI! JR The ramps were divided into compete in an international design After six rounds of competition, three segments at IS, 30, and 4S competition. Two additional stu- D~vid Arguelles '01 beat out over degree inclines with a hole at the dents who will later be selected will 130 students to become the champi- end of each incline. Robots scored compete as well. on of "Mech Everest," this year's points by dropping the pucks into 2.;0 Design Competition. these holes and scored more points Last-minute addition brings victory The contest is the culmination of for pucks dropped into higher holes. Each robot could carry up to ten the Des ign and Engineering 1 The course was designed by Roger pucks to drop in the holes. Students (2,.007) taught by Professor S. Cortesi '99, a student of Slocum. could request an additional ten Alexander H. Slocum '82. Some robots used suction to pucks which could not be carried in Kurtis G. McKenney '01, who keep their treads from slipping the robot body. Arguelles put these finished in second place, and third down the table, some clung to the in a light wire contraption pulled by p\~ce finisher Christopher K. -

De Classic Album Collection

DE CLASSIC ALBUM COLLECTION EDITIE 2013 Album 1 U2 ‐ The Joshua Tree 2 Michael Jackson ‐ Thriller 3 Dire Straits ‐ Brothers in arms 4 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born in the USA 5 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Rumours 6 Bryan Adams ‐ Reckless 7 Pink Floyd ‐ Dark side of the moon 8 Eagles ‐ Hotel California 9 Adele ‐ 21 10 Beatles ‐ Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band 11 Prince ‐ Purple Rain 12 Paul Simon ‐ Graceland 13 Meat Loaf ‐ Bat out of hell 14 Coldplay ‐ A rush of blood to the head 15 U2 ‐ The unforgetable Fire 16 Queen ‐ A night at the opera 17 Madonna ‐ Like a prayer 18 Simple Minds ‐ New gold dream (81‐82‐83‐84) 19 Pink Floyd ‐ The wall 20 R.E.M. ‐ Automatic for the people 21 Rolling Stones ‐ Beggar's Banquet 22 Michael Jackson ‐ Bad 23 Police ‐ Outlandos d'Amour 24 Tina Turner ‐ Private dancer 25 Beatles ‐ Beatles (White album) 26 David Bowie ‐ Let's dance 27 Simply Red ‐ Picture Book 28 Nirvana ‐ Nevermind 29 Simon & Garfunkel ‐ Bridge over troubled water 30 Beach Boys ‐ Pet Sounds 31 George Michael ‐ Faith 32 Phil Collins ‐ Face Value 33 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born to run 34 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Tango in the night 35 Prince ‐ Sign O'the times 36 Lou Reed ‐ Transformer 37 Simple Minds ‐ Once upon a time 38 U2 ‐ Achtung baby 39 Doors ‐ Doors 40 Clouseau ‐ Oker 41 Bruce Springsteen ‐ The River 42 Queen ‐ News of the world 43 Sting ‐ Nothing like the sun 44 Guns N Roses ‐ Appetite for destruction 45 David Bowie ‐ Heroes 46 Eurythmics ‐ Sweet dreams 47 Oasis ‐ What's the story morning glory 48 Dire Straits ‐ Love over gold 49 Stevie Wonder ‐ Songs in the key of life 50 Roxy Music ‐ Avalon 51 Lionel Richie ‐ Can't Slow Down 52 Supertramp ‐ Breakfast in America 53 Talking Heads ‐ Stop making sense (live) 54 Amy Winehouse ‐ Back to black 55 John Lennon ‐ Imagine 56 Whitney Houston ‐ Whitney 57 Elton John ‐ Goodbye Yellow Brick Road 58 Bon Jovi ‐ Slippery when wet 59 Neil Young ‐ Harvest 60 R.E.M. -

Bubbles S4,4 Vili Hr ' Still Seeks 874ßnshernmoroed ' Ilu G-Tr Damages"

Park studies alternati ,Library hoard reviews to soariñginsurance rates annexation defeat atpolls Eileen Hlrschfeld . by Sylvia Dalrysnpie Because of the soaring cooto ofssronce crises. "We must find,tionto the park diatrictforany in- Reporting on the Nov. 5 cIen- According to the attorney, liabifity insurance, park districtwayn to cat awsaace (liability) jsryelaisn,"hesaid. lino at the Niles Library Board precinct 74 in half io and 1mB out' Commissioners are considering claims because ifJfr risk factors Berrafato àdmitted'it's ost on Meeting, the library attorneyof the District hut residents adopting a program waiverinvolved in:,recrealional "ahoolatesolution"tothe said the annexation referendum there, regardless of where they classeforparticipantsin programo," he naid. liability insurance problem, hot it 'failed io two areas fo be annexed lived, voted for alt three itesss. recreational activitien. 1f the meansre io adopted, it is o step in the right directiso. hut was passed io the Nites He 'said there was a According to board attorney wonld meanallporlicipanlu in Programs cited which hove a Public Library District. By law,."mathematical posaibility" the - Gabriel Berrofoto, the park programo must sign a waiver in certain degree of rink were the referendum would have to referendûmcoutd have passed district, like other governmentot an activity which conld result in volleyball, softball, ice skating, pass in areas to be annexed as, and booed members could decide bodies, is facing o sermon in- injury.This wosld give prnlec- Continsedsa Page 43 wellasthe District. - Csntirnied an Page 43 - Bubbles s4,4 Vili hr ' still seeks 874ßNShernmoRoed ' iLu g-tr damages" ' 25° per copy VOL 29, NO. -

POWDERKEG" BALKAN THEATRE 1.0 User's Manual

BALKAN THEATRE - USER'S MANUAL "POWDERKEG" BALKAN THEATRE 1.0 User's manual Ó Falcon 4 is Intellectual Property of Infogrames Inc. 1 rev. 10c 2 BALKAN THEATRE - USER'S MANUAL Table of contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................5 Producer’s Notes.....................................................................................................................6 Download Locations................................................................................................................9 System Requirements...........................................................................................................10 Installation Instructions ........................................................................................................11 Preparing for Installation ......................................................................................................11 Installing the theater files .....................................................................................................11 Theater Activation................................................................................................................12 Additional patches................................................................................................................13 Known Issues and Common Problems...............................................................................14 Balkan Theater Features .......................................................................................................15 -

Engaging Stories

ENGAGING STORIES: MEANINGS, GOODNESS, AND IDENTITY IN DAILY LIFE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by John Adam Armstrong August 2015 © 2015 John Adam Armstrong ENGAGING STORIES: MEANINGS, GOODNESS, AND IDENTITY IN DAILY LIFE John Adam Armstrong, Ph. D. Cornell University 2015 With this dissertation I’ve attempted to encircle the idea of engagement—a term that's becoming more and more popular of late as public institutions attempt to frame how exactly they work with, for, or on, the public. In this work, I address four questions. What is engagement, institutionally speaking? How might institutions need to reconsider engagement? What is engagement for me? And ultimately, so what? The short answer is that engagement is a story. It's a story we tell ourselves about how people (should) interact with one another to make the world as it is, the way it should be. That being said, there are many different stories of engagement that fit this rubric—from unjust wars to happy marriages. They develop different characters, different settings, and different meanings, and in the end these stories have different morals with different consequences. These differences matter. With this dissertation I try to do away with some of the muddle between these different stories. I am not trying to do away with difference—just trying to give difference fair play. I also tell a very different story of engagement gleaned from my own experience and the experiences of a number of others in Tompkins County, NY. -

A Few Good Men a La Carte a La Mode Abacus Abbey Road Abel

A Few Good Men A La Carte A La Mode Abacus Abbey Road Abel Abelard Abigail Abracadabra Academic, The Acushla Adagio Addine Adonis Adventurer, The Aesop Afterglow Against All Odds Agassiz Agenda, Hidden Aglaia Aglow Agni Agnostic, The Agon Agricola Aiden Aigretter Aik Akido Ainslie Ain't Half Hot Ain't Misbehavin Ain't She Sweet Ain't That Hot Air Combat Air Fox Air Hawk Air Supply Air Seattle Airfighter Airlord Airtight Alibi Airtramp Airy Alf Ajax Ajay Ajeeb Akado Akau Akim Akim Tamiroff Akimbo Akira Al Capp Al Jolsen Al Kader Al Rakim Al Sirat Alabama Alabaster Doll Alakazam Alan Ladd Alaskan Albert Finney Alcazar Alceste Alchemist Alchise Alder Ale Berry Ale 'N 'Arty Ale Silver Alectryon Alert Command Alexon Alfai Alfana Alfredo Alfresco Alias Jack Alias Smith Alice B Toklus Alice Fay Alice Love Alida Alien, The Alien Factor Alien Outlaw Alienator Alix All Bluff All Chic All Class All Fired Upp All Front All Go All Serene All That Jazz Allegro Allemand Alley Kat Alley Oop Allrounder Allunga Alluring Ally Sloper Alma Mater Alman Almeric Almond Blossom Almost a Tramp Almost an Angel Alpha Omega Alphonse Alsace Alter Ego Althea Alvin Purple Always There Alwina Alzire Amadis Amagi Amalthea Amarco Amaretoo Amasis Amatian Amazing Man Amazon Queen Amber Blaze Amberlight Ambrose Ambrosia Amethyst Ami Noir Amigus Amir Amlet Amontillado Amoretti Amphora Amundson Analie Anchisis Anchorman Andante Ando Andrea Doria Andrei Androcles Andromeda Andy Capp Andy Pandy Angel Eyes Angel Heart Angela Lansbury Angele Angelica Angeline Angelique Angie Baby -

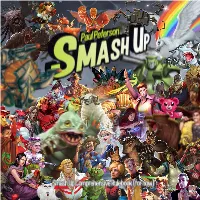

(From the Bigger Geekier Box Rulebook)!

1 The LeasT Funny smash up RuLebook eveR conTenTs Smash Up is a fght for 2–4 players, ages 14 and up. Objective ....................................................2 The Expanding Universe Game Contents...............................................2 From its frst big bang, the Smash Up universe The Expanding Universe.........................................................2 objecTive has expanded until our frst Big Geeky Box How to Use This Book............................................................2 became too small to hold it all! So we took that Know Your Cards! ............................................3 Your goal is nothing short of total global domination! box and made it better, stronger, faster, bigger. Meet These Other Cards! .....................................3 Use your minions to crush enemy bases. The frst Not only does this new box hold all the cards, Setup ........................................................4 player to score 15 victory points (VP) wins! this rulebook holds all the rules as well, or at Sample Setup ................................................4 least everything published up to now, all in one Kickin’ It Queensberry.......................................................... 4 convenient if not terribly funny 32-page package. As the Game Turns / The Phases of a Turn . 5 Game conTenTs The Big Score ................................................6 This glorious box of awesome contains: How to Use This Book Me First! ....................................................................... 6 Awarding -

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music By Jayson Makoto Chun The year 2013 proved a record-setting year in Japanese popular music. The male idol group Arashi occupied the spot for the top-selling album for the fourth year in a row, matching the record set by female singer Utada Hikaru. Arashi, managed by Johnny & Associates, a talent management agency specializing in male idol groups, also occupied the top spot for artist total sales while seven of the top twenty-five singles (and twenty of the top fifty) that year also came from Johnny & Associates groups (Oricon 2013b).1 With Japan as the world’s second largest music market at US$3.01 billion in sales in 2013, trailing only the United States (RIAJ 2014), this talent management agency has been one of the most profitable in the world. Across several decades, Johnny Hiromu Kitagawa (born 1931), the brains behind this agency, produced more than 232 chart-topping singles from forty acts and 8,419 concerts (between 2010 and 2012), the most by any individual in history, according to Guinness World Records, which presented two awards to Kitagawa in 2010 (Schwartz 2013), and a third award for the most number-one acts (thirty-five) produced by an individual (Guinness World Record News 2012). Beginning with the debut album of his first group, Johnnys in 1964, Kitagawa has presided over a hit-making factory. One should also look at R&B (Rhythm and Blues) singer Utada Hikaru (born 1983), whose record of four number one albums of the year Arashi matched. -

National Perspectives on Nuclear Disarmament

NATIONAL PERSPECTIVES ON NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT EDITED BY: Barry M. Blechman Alexander K. Bollfrass March 2010 Copyright ©2010 The Henry L. Stimson Center Cover design by Shawn Woodley All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .....................................................................................................................v Introduction ...........................................................................................................vii BRAZIL | A Brazilian Perspective on Nuclear Disarmament Marcos C. de Azambuja.....................................................................1 CHINA | China’s Nuclear Strategy in a Changing World Stategic Situation Major General Pan Zhenqiang (Retired)........................................13 FRANCE | French Perspectives on Nuclear Weapons and Nuclear Disarmament Bruno Tertrais ..................................................................................37 INDIA | Indian Perspectives on the Global Elimination of Nuclear Weapons Rajesh M. Basrur .............................................................................59 IRAN | Iranian Perspectives on the Global Elimination of Nuclear Weapons Anoush Ehteshami............................................................................87 -

CLEVELAND APL ADOPTIONS: June 2015 Animal Name Species Primary Breed Age As Months Sex New Hometown Adoption Location 1 Wave Cat Snowshoe 146 M CLEVELAND Cat Playroom

Cat adoptions: 397 Dog adoptions: 157 Rabbit adoptions: 6 Ferret adoptions: 1 Guinea Pig adoptions: 1 Hamster adoptions: 3 CLEVELAND APL ADOPTIONS: June 2015 Animal Name Species Primary Breed Age As Months Sex New Hometown Adoption Location 1 Wave Cat Snowshoe 146 M CLEVELAND Cat Playroom 11 Eel Cat Domestic Shorthair 110 M BEACHWOOD Cat Adoption 2 Surf Cat Snowshoe 104 M CLEVELAND Cat Playroom 3 Shell Cat Domestic Medium Hair 50 F SHELBY Cat Playroom Abigail Cat Domestic Medium Hair 25 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption, EAC Adelaide Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Adley Cat Domestic Shorthair 52 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption, EAC Aerosmith Cat Domestic Shorthair 62 M CLEVELAND Cat Adoption, EAC Alex Cat Domestic Shorthair 2 F INDEPENDENCE Cat Adoption Alice Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 F LAKEWOOD Cat Adoption Alonzo Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 M CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Alvin Cat Domestic Medium Hair 4 M CLEVELAND Lobby Amber Cat Domestic Shorthair 98 F BROADVIEW HEIGHTS Cat Adoption, EAC Anabelle Cat Domestic Shorthair 75 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Anastasia Cat Domestic Longhair 3 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Anastasia Cat Tonkinese 86 F STRONGSVILLE Cat Adoption, EAC Anita Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Aroma Cat Domestic Medium Hair 18 F EASTLAKE Cat Adoption Arthur Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 M CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Arthur Cat Domestic Shorthair 4 M CLEVELAND Cat Admitting Atticus Cat Domestic Shorthair 2 M LAKEWOOD Cat Adoption Audrey-Anne Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 F CLEVELAND Lobby Augusta Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 F MEDINA -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRSTSESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRSTSESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MARCH 15, 2005 No. 31 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was in a global war against terrorism, we possible leadership, the finest training, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- have military forces deployed around and up-to-date and working equipment, pore (Mr. PORTER). the world, and we are involved in two protective armor body, and vehicle f shooting wars in Iraq and in Afghani- armor. We in Congress have a duty to stan. These deployments and these con- ensure that they have all the tools DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER flicts are putting a terrible strain on they need to succeed on the battlefield. PRO TEMPORE our military, on our troops, on our We also have a duty to provide for The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- equipment, on our military families, their families while they are deployed fore the House the following commu- on our defense budget, and on our na- in service to our great Nation. We have nication from the Speaker: tional economy. a duty to take care of the families of WASHINGTON, DC, I believe we will overcome these those who are killed and those who are March 15, 2005. challenges because we have the great- wounded. I hereby appoint the Honorable JON C. POR- est treasure in the world, our service Mr. Speaker, we also have a duty to TER to act as Speaker pro tempore on this men and women, who are selflessly our citizen soldiers, members of the day. -

A Study of the Three Anglo-Dutch Wars, 1652-1674 William Terry Curtler

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Summer 1967 Iron vs. gold : a study of the three Anglo-Dutch wars, 1652-1674 William Terry Curtler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Curtler, William Terry, "Iron vs. gold : a study of the three Anglo-Dutch wars, 1652-1674" (1967). Master's Theses. Paper 262. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRON VS. GOLD A STUDY OF THE THfu~E ANGI.. 0-DUTCH WARS• 16.52-1674 BY WILLIAM TERRY CURTLER A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TH8 GRADUATE r'ACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IM HISTORY AUGUST, 1967 t.JGRARY UNJVERSHY QF RJCHMONI) VUfQINfA ii Approved for the Department of History and the Graduate School by ciia'.Irman of tne His.tory .Department 111 PREFACE· The purpose of this paper is to show that, as the result ot twenty-two years of intermittent warfare between England and the Netherlands, the English navy became es• tablished as the primary naval power of Europe. Also, I intend to illustrate that, as a by-product of this naval warfare, Dutch trade was seriously hurt, with the· major benefactors of this Dutch loss of trade being the English. This paper grew out of a seminar paper on the first Anglo•Dutch war for a Tudor and Stuart English History graduate seminar class taught in the fall of 1966 by Dr.