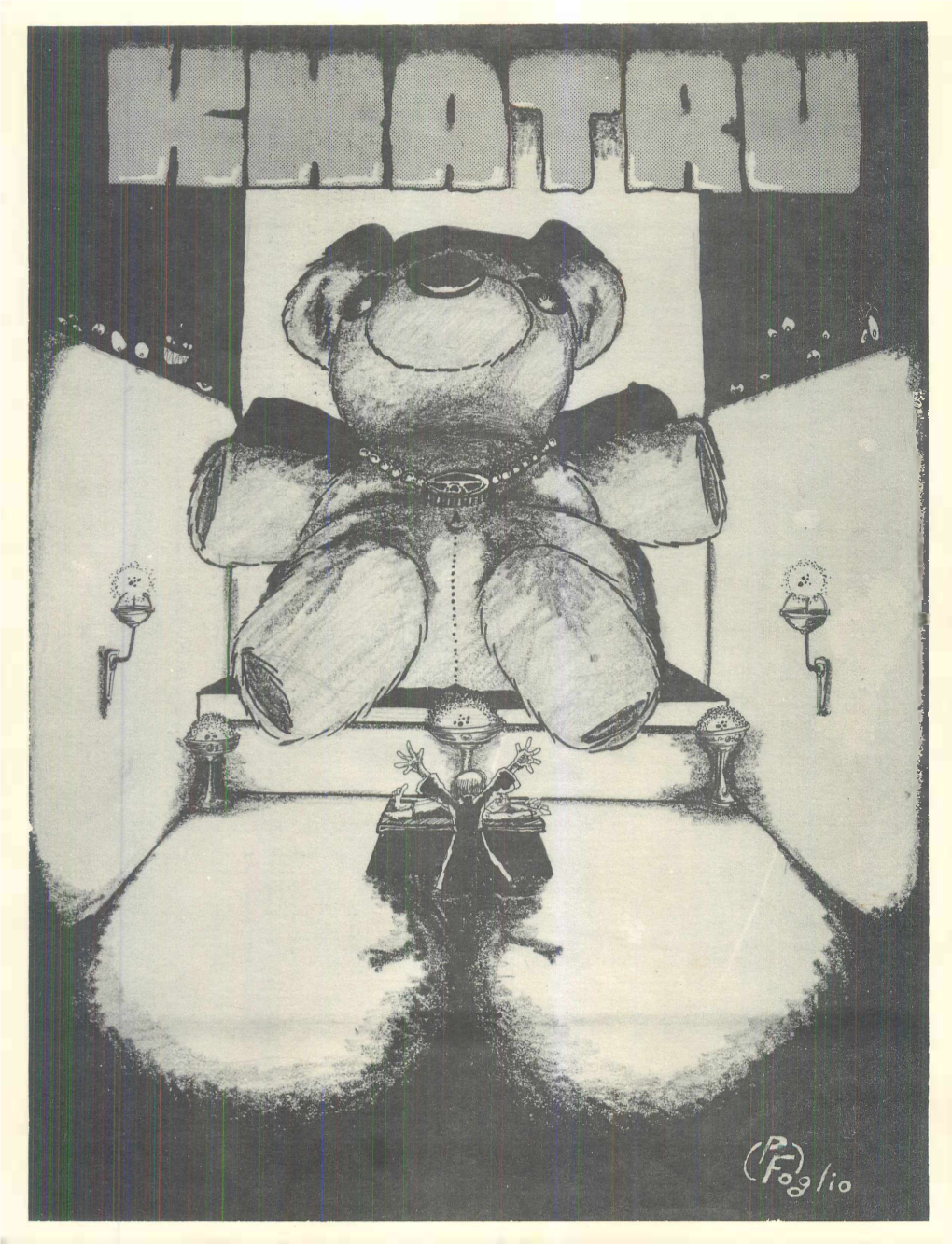

KHATRU 7, 2/78 Review of Ursula K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sandspur, Vol 90, No 05, November 22, 1983

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 11-22-1983 Sandspur, Vol 90, No 05, November 22, 1983 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol 90, No 05, November 22, 1983" (1983). The Rollins Sandspur. 1616. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1616 Volume 90 Number 5 photo: jerry Uelsmann (story, page 5) Rollins College Sandspur, November 22,1983 pg. 2 The Haagen-Dazs Collection Haagen-Dazs presents the two straw mi Ik Nlv Arte shake A frosty smooth shake so thick and rich, Fine Lingerie • Foundations vou'll probably want two straws to drink it! Swimwear • Loungewear 218 Park Avenue N. Winter Park, FL 32789 Haagen-Dazs Telephone: 647-5519 ^^ Park Avenue 116 E. New England Ave. • Winter Park • 644-1611 Solar Heated Water fit FAIRBANKS EASTERN POLYCLEfiN GfiS fiND BEVERAGE Just One Block North Your Complete Laundromat of Rollins Campus Just One Block North * Discount Prices On Our of Rollins Campus Large Assortment of Domestic and Imported Beer Soda and Snacks Daily Newspapers and Magazines SELF SERVICE (New York Times, Wall Street Journal Orlando Sentinel) Wash And Dry FULL SERVICE Dry Cleaning Don't Forget To Check Oat Oar Wash, Dry. -

The Yes Catalogue ------1

THE YES CATALOGUE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK M P LTD. AUG 1968 2. MAGPIE TV UK ITV 31 DEC 1968 ???? (Rec. 31 Dec 1968) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK M P LTD. JAN 1969 Yes! 56w 4. TOP GEAR RADIO UK BBC 12 JAN 1969 Dear Father (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Anderson/Squire Everydays (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Stills Sweetness (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Anderson/Squire/Bailey Something's Coming (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Sondheim/Bernstein 5. TOP GEAR RADIO UK BBC 23 FEB 1969 something's coming (rec. ????) sondheim/bernstein (Peter Banks has this show listed in his notebook.) 6. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK m p ltd. MAR 1969 (Yes was featured in this edition.) 7. GOLDEN ROSE TV FESTIVAL tv SWITZ montreux 24 apr 1969 - 25 apr 1969 8. radio one club radio uk bbc 22 may 1969 9. THE JOHNNIE WALKER SHOW RADIO UK BBC 14 JUN 1969 Looking Around (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Anderson/Squire Sweetness (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Anderson/Squire/Bailey Every Little Thing (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Lennon/McCartney 10. JAM TV HOLL 27 jun 1969 11. SWEETNESS 7 PS/m/BL & YEL FRAN ATLANTIC 650 171 27 jun 1969 F1 Sweetness (Edit) 3:43 J. Anderson/C. Squire (Bailey not listed) F2 Something's Coming' (From "West Side Story") 7:07 Sondheim/Bernstein 12. SWEETNESS 7 M/RED UK ATL/POLYDOR 584280 04 JUL 1969 A Sweetness (Edit) 3:43 Anderson/Squire (Bailey not listed) B Something's Coming (From "West Side Story") 7:07 Sondheim/Bernstein 13. -

Yes - Progeny: Seven Shows from Seventy-Two

Yes - Progeny: Seven Shows from Seventy-Two Scritto da Gianluca Livi Giovedì 18 Giugno 2015 18:49 Progeny: Seven Shows from Seventy-Two è l'ultima uscita postuma degli Yes. Si tratta delle registrazioni live da cui, in parte, fu estratto il famoso album live Yessongs del 1973. E' stato edito in tre versioni: 1) quella monumentale di 14 CD, che cattura sette spettacoli completi registrati nel 1972 nel tour di Close to the Edge. 2) una versione edit di 2-CD 3) la versione in vinile di quest'ultima, costituita da 3 LP E' qui recensita l'ultima uscita discografica, essendo chi scrive appassionato di vinile. Questa recensione deve essere scissa in due parti: Nella prima,qui l'intervista deve essere al batterista necessariamente a firma di commentata chi scrive ) ela presentando scelta criticabile una discaletta limitare deciamente l'edizione inpiù vinile completa a soli ed3 LP, esaustiva cosa che (in a particolare, mio modesto mancano avviso, Perpetualrende questo Change, titolo The un prodotto Fish e Starship quasi gemello Tropper, di Yessongs.registrati in Anzi, occasione a dirla del tutta, tour Yessongs precedente). era anche più completo raccogliendo testimonianze esecutive dell'immenso Bill Bruford ( Confrontate voi stessi: questa la scaletta di YesSongs e a seguire quella di Progeny: YESSONGS Opening (Excerpt From 'Firebird Suite') Siberian Khatru Heart Of The Sunrise Perpetual Change And You And I Mood For A Day Excerpts From 'The Six Wives Of Henry VIII' 1 / 4 Yes - Progeny: Seven Shows from Seventy-Two Scritto da Gianluca Livi Giovedì 18 Giugno 2015 18:49 Roundabout I've Seen All Good People Long Distance Runaround-The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus) Close To The Edge Yours Is No Disgrace Starship Trooper PROGENY Opening (Excerpt From Firebird Suite) Siberian Khatru I've Seen All Good People: Your Move / All Good People Heart of the Sunrise Clap/Mood For A Day And You And I Close To The Edge Excerpts From "The Six Wives of Henry VIII" Roundabout Yours is No Disgrace Tuttavia, va detto che la qualità di Progeny è decisamente superiore a quella di YesSongs. -

"You Remind Me of the Babe with the Power": How Jim Henson Redefined the Portrayal of Young Girls in Fanastial Movies in His Film, Labyrinth

First Class: A Journal of First-Year Composition Volume 2015 Article 7 Spring 2015 "You Remind Me of the Babe With the Power": How Jim Henson Redefined the orP trayal of Young Girls in Fanastial Movies in His Film, Labyrinth Casey Reiland Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/first-class Recommended Citation Reiland, C. (2015). "You Remind Me of the Babe With the Power": How Jim Henson Redefined the Portrayal of Young Girls in Fanastial Movies in His Film, Labyrinth. First Class: A Journal of First-Year Composition, 2015 (1). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/ first-class/vol2015/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in First Class: A Journal of First-Year Composition by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. “YOU REMIND ME OF THE BABE WITH THE POWER”: HOW JIM HENSON REDEFINED THE PORTRAYAL OF YOUNG GIRLS IN FANTASTICAL MOVIES IN HIS FILM, LABYRINTH By Casey Reiland, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Instructor: Dr. Jessica McCort When I was fourteen, I was very surprised when one day my mom picked me up from school and plopped a DVD of David Bowie in tights posing with a Muppet into my hands. “Remember this?!” She asked excitedly. I stared quizzically at the cover and noticed it was titled, Labyrinth. For a moment I was confused as to why my mother would bother buying me some strange, fantasy movie from the eighties, but suddenly, it clicked. I had grown up watching this film; in fact I had been so obsessed with it that every time we went to our local movie rental store I would beg my mom to rent it for a couple of nights. -

50% Off List Copy

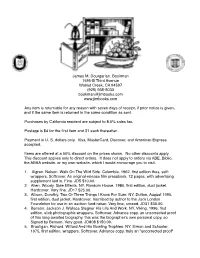

! ! ! ! ! ! James M. Dourgarian, Bookman! 1595-B Third Avenue! Walnut Creek, CA 94597! (925) 935-5033! [email protected]" www.jimbooks.com! ! Any item is returnable for any reason with seven days of receipt, if prior notice is given, and! if the same item is returned in the same condition as sent.! !Purchases by California resident are subject to 8.5% sales tax.! !Postage is $4 for the first item and $1 each thereafter.! Payment in U. S. dollars only. Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and American Express accepted.! ! Items are offered at a 50% discount on the prices shown. No other discounts apply. This discount applies only to direct orders. It does not apply to orders via ABE, Biblio, the! ABAA website, or my own website, which I would encourage you to visit.! 1. Algren, Nelson. Walk On The Wild Side. Columbia, 1962, first edition thus, self- wrappers. Softcover. An original-release film pressbook, 12 pages, with advertising supplement laid in. Fine. JD5 $10.00.! 2. Allen, Woody. Side Effects. NY, Random House, 1980, first edition, dust jacket. Hardcover. Very fine. JD17 $25.00.! 3. Allison, Dorothy. Two Or Three Things I Know For Sure. NY, Dutton, August 1995, first edition, dust jacket. Hardcover. Inscribed by author to the Jack London Foundation for use in an auction fund-raiser. Very fine, unread. JD31 $30.00.! 4. Benson, Jackson J. Wallace Stegner His Life And Work. NY, Viking, 1996, first edition, slick photographic wrappers. Softcover. Advance copy, an uncorrected proof of this long-awaited biography, this was the biographer's own personal copy, so Signed by Benson. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Jim Henson's Fantastic World

Jim Henson’s Fantastic World A Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department Produced in conjunction with Jim Henson’s Fantastic World, an exhibition organized by The Jim Henson Legacy and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. The exhibition was made possible by The Biography Channel with additional support from The Jane Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson. Jim Henson’s Fantastic World Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department, 2009 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Teachers ............................................................................................... 3 Jim Henson: A Biography ............................................................................................... 4 Text Panels from Exhibition ........................................................................................... 7 Key Characters and Project Descriptions ........................................................................ 15 Pre Visit Activities:.......................................................................................................... 32 Elementary Middle High School Museum Activities: ........................................................................................................ 37 Elementary Middle/High School Post Visit Activities: ....................................................................................................... 68 Elementary Middle/High School Jim Henson: A Chronology ............................................................................................ -

Idvp010cd Couriernew

Print Version Page 1 of 2 Print Page Permutations of Yes By Tom Von Malder (Created: Wednesday, August 22, 2007 11:09 PM EDT) Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, Howe: An Evening of Yes Music Plus (Voiceprint DVD, 143 min.). Consisting of four-fifths of the classic lineup of Yes in the Seventies (only Chris Squire is missing), this quartet, put together by Jon Anderson, recorded an eponymous album in 1989 and then embarked on a worldwide tour. This generous-length show was captured on the American leg of the tour. It opens with brief solo sets by vocalist Anderson (“Time and a Word,” “Owner of a Lonely Heart”), who enters the auditorium from the rear and sings while walking down the aisle to the stage; guitarist Steve Howe (a couple of acoustic instrumentals) and keyboardist Rick Wakeman (“Catherine Parr,” “Merlin the Magician”), before the whole group launches into Yes’ classic “Long Distance Runaround” at the 24-minute mark. The song contains a solo by drummer Bill Bruford. Then comes “Birthright” from their one album (“Teakbois,” the bouncy rocker “Brother of Mine” and “Themes” also are covered from the disc). The wonderful central core is a trio of Yes songs: “And You and I,” “I’ve Seen All Good People” and a 19- minute “Close to the Edge.” The show ends with “Roundabout,” then an encore of “Starship Troop” after the credits roll. Grade A- Rick Wakeman: The Other Side of Rick Wakeman (MVD Visual DVD, 112 min.). This unusual release finds progressive rock keyboardist Wakeman on stage in a small club, with just a microphone and a grand piano. -

April 2021 New Releases

April 2021 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s featured exclusives inside PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 79 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 11 ROY ORBISON - HEMINGWAY, A FILM BY JON ANDERSON - FEATURED RELEASES Video THE CAT CALLED DOMINO KEN BURNSAND LYNN OLIAS OF SUNHILLOW: 48 NOVICK. ORIGINAL 2 DISC EXPANDED & Film MUSIC FROM THE PBS REMASTERED DOCUMENTARY Films & Docs 50 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 78 Order Form 81 Deletions & Price Changes 84 THE FINAL COUNTDOWN DONNIE DARKO (UHD) ACTION U.S.A. 800.888.0486 (3-DISC LIMITED 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 EDITION/4K UHD+BLU- www.MVDb2b.com RAY+CD) WO FAT - KIM WILSON - SLY & ROBBIE - PSYCHEDELONAUT TAKE ME BACK RED HILLS ROAD DONNIE DARKO SEES THE LIGHT! The 2001 thriller DONNIE DARKO gets the UHD/4K treatment this month from Arrow Video, a 2-disc presentation that shines a crisp light on this star-studded film. Counting PATRICK SWAYZE and DREW BARRYMORE among its luminous cast, this first time on UHD DONNIE DARKO features the film and enough extras to keep you in the Darko for a long time! A lighter shade of dark is offered in the limited-edition steelbook of ELVIRA: MISTRESS OF THE DARK, a horror/comedy starring the horror hostess. Brand new artwork and an eye-popping Hi-Def presentation. Blue Underground rises again in the 4K department, with a Bluray/UHD/CD special of THE FINAL COUNTDOWN. The U.S.S. Nimitz is hurled back into time and can prevent the attack on Pearl Harbor! With this new UHD version, the KIRK DOUGLAS-led crew can see the enemy with crystal clarity! You will not believe your eyes when you witness the Animal Kingdom unleashed with two ‘Jaws with Claws’ horror movies from Severin Films, GRIZZLY and DAY OF THE ANIMALS. -

40Th FREE with Orders Over

By Appointment To H.R.H. The Duke Of Edinburgh Booksellers London Est. 1978 www.bibliophilebooks.com ISSN 1478-064X CATALOGUE NO. 366 OCT 2018 PAGE PAGE 18 The Night 18 * Before FREE with orders over £40 Christmas A 3-D Pop- BIBLIOPHILE Up Advent th Calendar 40 with ANNIVERSARY stickers PEN 1978-2018 Christmas 84496, £3.50 (*excluding P&P, Books pages 19-20 84760 £23.84 now £7 84872 £4.50 Page 17 84834 £14.99 now £6.50UK only) 84459 £7.99 now £5 84903 Set of 3 only £4 84138 £9.99 now £6.50 HISTORY Books Make Lovely Gifts… For Family & Friends (or Yourself!) Bibliophile has once again this year Let us help you find a book on any topic 84674 RUSSIA OF THE devised helpful categories to make useful you may want by phone and we’ll TSARS by Peter Waldron Including a wallet of facsimile suggestions for bargain-priced gift buying research our database of 3400 titles! documents, this chunky book in the Thames and Hudson series of this year. The gift sections are Stocking FREE RUBY ANNIVERSARY PEN WHEN YOU History Files is a beautifully illustrated miracle of concise Fillers under a fiver, Children’s gift ideas SPEND OVER £40 (automatically added to narration, starting with the (in Children’s), £5-£20 gift ideas, Luxury orders even online when you reach this). development of the first Russian state, Rus, in the 9th century. tomes £20-£250 and our Yuletide books Happy Reading, Unlike other European countries, Russia did not have to selection. -

Australian SF News 37

FBONY BOOKS 1984 DITMAR AWARD ANNOUNCE FIRST Nominations PUBLICATION THE AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS BEST AUSTRALIAN LONG SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY THE TEMPTING OF THE WITCHKING - Russell Blackford (Cory f, Collins THE JUDAS MANDALA - Damien Broderick (Timescape) VALENCIES - Damien Broderick and Rory Barnes (U.Queensland Press) KELLY COUNTRY - A.Bertram Chandler (Penguin) YESTERDAY'S MEN - George Turner (Faber ) THOR'S HAMMER - Wynne Whiteford (Cory and Collins) BEST AUSTRALIAN SHORT SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY "Crystal Soldier" - Russell Blackford (DREAMWORKS, ed. David King, Norstrilia Press ) "Life the Solitude" - Kevin McKay "Land Deal" - Gerald Murnane "Above Atlas His Shoulders" - Andrew Whitmore BEST INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY THE BIRTH OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF ANTARCTICA - John Calvin Batchelor (Dial Press) THE TEMPTING OF THE WITCHKING - Russell Blackford (Cory 6 Collins) DR WHO - B.B.C PILGERMAN - Russell Hoban (Jonathan Cape) YESTERDAY'S MEN - George Turner (Faber ) THOR'S HAMMER - Wynne Whiteford (Cory 8 Collins) BEST AUSTRALIAN FANZINE AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION NEWS - edited Merv Binns ORNITHOPTER/RATAPLAN - edited Leigh Edmonds SCIENCE FICTION - edited Van Ikin THYME - edited Roger Weddall WAHF-FULL - edited Jack Herman BEST AUSTRALIAN FAN WRITER BEST AUSTRALIAN SF OR F ARTIST Leigh Edmonds Neville Bain Terry Frost Steph Campbell Jack Herman Mike Dutkiewicz Seth Lockwood Chris Johnston Nick Stathopoulos BEST AUSTRALIAN SF OR F CARTOONIST BEST AUSTRALIAN SF OR F EDITOR Bill Flowers Paul Collins Terry Frost Van Ikin Craig Hilton David King RUSSELL and JENNY BLACKFORD have announced Mike McGann Norstrilia Press the establishment of their new publishing John Packer (Rob Gerrand, Bruce Gillespie company EBONY BOOKS, and that they are Clint Strickland and Cary Handfield) publishing first up a new novel by DAMIEN BRODERICK titled TRANSMITTERS. -

Jon Anderson Dalai Angolul, Magyarul Jon Anderson`S Songs in English and in Hungarian

Szerény kísérlet az elveszett harmónia megtalálására Modest attempt to find the lost harmony Jon Anderson dalai angolul, magyarul Jon Anderson`s songs in English and in Hungarian 1 Jon Anderson 2 Table of Contents Tartalomjegyzék So Far Away, So Clear - Oly messzi, oly tiszta (1975)______________________________ 4 Olias of Sunhillow (1976)____________________________________________________ 5 Short Stories - Novellák (1980) ______________________________________________ 12 Song of Seven – A hét dala (1980) ____________________________________________ 20 The Friends Of Mr. Cairo – Kairo úr barátai (1981) _____________________________ 32 Animation – Mozgatás (1982) _______________________________________________ 33 ¤ 3ULYDW &ROOHFWLR ¡£¢ 0DJiQJ\&MWHPpQ __________________________________ 34 Three Ships - Három hajó (1985) ____________________________________________ 41 In The City Of Angels - Az angyalok városában (1988) ___________________________ 53 "LOVED BY THE SUN"(A NAP SZERETTE) ____________________________________ 73 Requiem For The Americas - Rekviem az amerikaiakért (1989) ____________________ 74 Page Of Life - Az élet oldala (1991) ___________________________________________ 78 Close To The Hype – Közel a feldobott állapothoz (1992)__________________________ 81 Dream - Álom (1992) ______________________________________________________ 82 Change We Must - Meg kell változnunk (1994) _________________________________ 87 Deseo (1994) ____________________________________________________________ 105 ¦ §©¨ ¦ ¦ ,WC¥ $ERX 7LP (OM| D LG