"You Remind Me of the Babe with the Power": How Jim Henson Redefined the Portrayal of Young Girls in Fanastial Movies in His Film, Labyrinth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autobituary: the Life And/As Death of David Bowie & the Specters From

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mourning Jake Cowan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13374 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13374 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jake Cowan, “Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mourning”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13374 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13374 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mournin... 1 Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mourning Jake Cowan La mort m’attend dans un grand lit Tendu aux toiles de l’oubli Pour mieux fermer le temps qui passé — Jacques Brel, « La Mort » 1 For all his otherworldly strangeness and space-aged shimmer, the co(s)mic grandeur and alien figure(s) with which he was identified, there was nothing more constant in David Bowie’s half-century of song than death, that most and least familiar of subjects. From “Please Mr. Gravedigger,” the theatrical closing number on his 1967 self-titled debut album, to virtually every track on his final record nearly 50 years later, the protean musician mused perpetually on all matters of mortality: the loss of loved ones (“Jump They Say,” about his brother’s suicide), the apocalyptic end of the world (“Five Years”), his own impending passing. -

50% Off List Copy

! ! ! ! ! ! James M. Dourgarian, Bookman! 1595-B Third Avenue! Walnut Creek, CA 94597! (925) 935-5033! [email protected]" www.jimbooks.com! ! Any item is returnable for any reason with seven days of receipt, if prior notice is given, and! if the same item is returned in the same condition as sent.! !Purchases by California resident are subject to 8.5% sales tax.! !Postage is $4 for the first item and $1 each thereafter.! Payment in U. S. dollars only. Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and American Express accepted.! ! Items are offered at a 50% discount on the prices shown. No other discounts apply. This discount applies only to direct orders. It does not apply to orders via ABE, Biblio, the! ABAA website, or my own website, which I would encourage you to visit.! 1. Algren, Nelson. Walk On The Wild Side. Columbia, 1962, first edition thus, self- wrappers. Softcover. An original-release film pressbook, 12 pages, with advertising supplement laid in. Fine. JD5 $10.00.! 2. Allen, Woody. Side Effects. NY, Random House, 1980, first edition, dust jacket. Hardcover. Very fine. JD17 $25.00.! 3. Allison, Dorothy. Two Or Three Things I Know For Sure. NY, Dutton, August 1995, first edition, dust jacket. Hardcover. Inscribed by author to the Jack London Foundation for use in an auction fund-raiser. Very fine, unread. JD31 $30.00.! 4. Benson, Jackson J. Wallace Stegner His Life And Work. NY, Viking, 1996, first edition, slick photographic wrappers. Softcover. Advance copy, an uncorrected proof of this long-awaited biography, this was the biographer's own personal copy, so Signed by Benson. -

Jim Henson's Fantastic World

Jim Henson’s Fantastic World A Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department Produced in conjunction with Jim Henson’s Fantastic World, an exhibition organized by The Jim Henson Legacy and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. The exhibition was made possible by The Biography Channel with additional support from The Jane Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson. Jim Henson’s Fantastic World Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department, 2009 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Teachers ............................................................................................... 3 Jim Henson: A Biography ............................................................................................... 4 Text Panels from Exhibition ........................................................................................... 7 Key Characters and Project Descriptions ........................................................................ 15 Pre Visit Activities:.......................................................................................................... 32 Elementary Middle High School Museum Activities: ........................................................................................................ 37 Elementary Middle/High School Post Visit Activities: ....................................................................................................... 68 Elementary Middle/High School Jim Henson: A Chronology ............................................................................................ -

Muppet Treasure Island Lisa Packard

Children's Book and Media Review Volume 38 Article 45 Issue 1 January 2017 2017 Muppet Treasure Island Lisa Packard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Packard, Lisa (2017) "Muppet Treasure Island," Children's Book and Media Review: Vol. 38 : Iss. 1 , Article 45. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr/vol38/iss1/45 This Movie Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Children's Book and Media Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Packard: Muppet Treasure Island Movie Review Title: Muppet Treasure Island Main Performers: Tim Curry, Billy Connolly, Jennifer Saunders Director: Brian Henson Reviewer: Lisa Packard Studio: Jim Henson Productions Year Released: 1996 Run Time: 99 minutes MPAA Rating: G Interest Level: Primary, Intermediate Rating: Outstanding Review Jim Hawkins works at an inn, but wishes to be an explorer. Billy Bones, a guy staying at the inn, tells a story about buried treasure and the pirates who buried it there. A nasty bunch of pirates show up and tell Bones that if he doesn’t hand over the treasure map, they’ll kill him. Bones gives Jim the map before he dies and Jim decides to go on an adventure with his friends Rizzo the Rat and Gonzo the Great. They hire a ship and meet the one-legged man Long John Silver. Captain Abraham Smollett (Kermit the Frog) doesn’t trust the crew and takes the treasure map from Jim so that pirates don’t take it from him. -

40Th FREE with Orders Over

By Appointment To H.R.H. The Duke Of Edinburgh Booksellers London Est. 1978 www.bibliophilebooks.com ISSN 1478-064X CATALOGUE NO. 366 OCT 2018 PAGE PAGE 18 The Night 18 * Before FREE with orders over £40 Christmas A 3-D Pop- BIBLIOPHILE Up Advent th Calendar 40 with ANNIVERSARY stickers PEN 1978-2018 Christmas 84496, £3.50 (*excluding P&P, Books pages 19-20 84760 £23.84 now £7 84872 £4.50 Page 17 84834 £14.99 now £6.50UK only) 84459 £7.99 now £5 84903 Set of 3 only £4 84138 £9.99 now £6.50 HISTORY Books Make Lovely Gifts… For Family & Friends (or Yourself!) Bibliophile has once again this year Let us help you find a book on any topic 84674 RUSSIA OF THE devised helpful categories to make useful you may want by phone and we’ll TSARS by Peter Waldron Including a wallet of facsimile suggestions for bargain-priced gift buying research our database of 3400 titles! documents, this chunky book in the Thames and Hudson series of this year. The gift sections are Stocking FREE RUBY ANNIVERSARY PEN WHEN YOU History Files is a beautifully illustrated miracle of concise Fillers under a fiver, Children’s gift ideas SPEND OVER £40 (automatically added to narration, starting with the (in Children’s), £5-£20 gift ideas, Luxury orders even online when you reach this). development of the first Russian state, Rus, in the 9th century. tomes £20-£250 and our Yuletide books Happy Reading, Unlike other European countries, Russia did not have to selection. -

Australian SF News 37

FBONY BOOKS 1984 DITMAR AWARD ANNOUNCE FIRST Nominations PUBLICATION THE AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS BEST AUSTRALIAN LONG SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY THE TEMPTING OF THE WITCHKING - Russell Blackford (Cory f, Collins THE JUDAS MANDALA - Damien Broderick (Timescape) VALENCIES - Damien Broderick and Rory Barnes (U.Queensland Press) KELLY COUNTRY - A.Bertram Chandler (Penguin) YESTERDAY'S MEN - George Turner (Faber ) THOR'S HAMMER - Wynne Whiteford (Cory and Collins) BEST AUSTRALIAN SHORT SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY "Crystal Soldier" - Russell Blackford (DREAMWORKS, ed. David King, Norstrilia Press ) "Life the Solitude" - Kevin McKay "Land Deal" - Gerald Murnane "Above Atlas His Shoulders" - Andrew Whitmore BEST INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY THE BIRTH OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF ANTARCTICA - John Calvin Batchelor (Dial Press) THE TEMPTING OF THE WITCHKING - Russell Blackford (Cory 6 Collins) DR WHO - B.B.C PILGERMAN - Russell Hoban (Jonathan Cape) YESTERDAY'S MEN - George Turner (Faber ) THOR'S HAMMER - Wynne Whiteford (Cory 8 Collins) BEST AUSTRALIAN FANZINE AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION NEWS - edited Merv Binns ORNITHOPTER/RATAPLAN - edited Leigh Edmonds SCIENCE FICTION - edited Van Ikin THYME - edited Roger Weddall WAHF-FULL - edited Jack Herman BEST AUSTRALIAN FAN WRITER BEST AUSTRALIAN SF OR F ARTIST Leigh Edmonds Neville Bain Terry Frost Steph Campbell Jack Herman Mike Dutkiewicz Seth Lockwood Chris Johnston Nick Stathopoulos BEST AUSTRALIAN SF OR F CARTOONIST BEST AUSTRALIAN SF OR F EDITOR Bill Flowers Paul Collins Terry Frost Van Ikin Craig Hilton David King RUSSELL and JENNY BLACKFORD have announced Mike McGann Norstrilia Press the establishment of their new publishing John Packer (Rob Gerrand, Bruce Gillespie company EBONY BOOKS, and that they are Clint Strickland and Cary Handfield) publishing first up a new novel by DAMIEN BRODERICK titled TRANSMITTERS. -

Ultimate Movie Collectables London - Los Angeles

Ultimate Movie Collectables London - Los Angeles Prop Store - London Office Prop Store - Los Angeles Office Great House Farm 9000 Fullbright Ave Chenies Chatsworth, CA 91311 Rickmansworth USA Hertfordshire Ph: +1 818 727 7829 WD36EP Fx: +1 818 727 7958 UK Contact: Ph: +44 1494 766485 Stephen Lane - Chief Executive Officer Fx: +44 1494 766487 [email protected] [INTRODUCTION] Prop Store Office: London Prop Store Office: Los Angeles How do you best serve your greatest passion in life? the pieces that they sought, but also establish the standards for finding, You make it your business. acquiring and preserving the props and costumes used in Hollywood’s most beloved films. In 1998, UK native Stephen Lane did just that. Stephen’s love for movies led him ENTER: THE PROP STORE OF LONDON to begin hunting for the same props and Stephen and his team came to market already looking beyond the business costumes that were used to create his of simply collecting and selling movie props. Instead, the Prop Store team favorite films. It was the early days of the set out like a band of movie archaeologists, looking to locate, research internet and an entire world of largely and preserve the treasure troves of important artifacts that hid in dark, isolated collectors was just beginning to sometimes forgotten corners all over the world. And it’s now thanks to come together. As Stephen began making Stephen’s vision and the hard work of his dedicated team that so many of friends and connections all over the world— film history’s most priceless artifacts have found their way into either the relationships that continue today—he loving hands of private collectors or, as one of Stephen’s greatest movie realized that he was participating in the explosion of a hobby that would heroes would say, “into a museum!” soon reach every corner of the globe. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

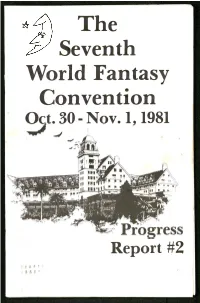

The Convention Itself

The Seventh World Fantasy Convention Oct. 30 - Nov. 1.1981 V ■ /n Jg in iiiWjF. ni III HITV Report #2 I * < ? I fl « f Guests of Honor Alan Garner Brian Frond Peter S. Beagle Master of Ceremonies Karl Edward Wagner Jack Rems, Jeff Frane, Chairmen Will Stone, Art Show Dan Chow, Dealers Room Debbie Notkin, Programming Mark Johnson, Bill Bow and others 1981 World Fantasy Award Nominations Life Achievement: Joseph Payne Brennan Avram Davidson L. Sprague de Camp C. L. Moore Andre Norton Jack Vance Best Novel: Ariosto by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro Firelord by Parke Godwin The Mist by Stephen King (in Dark Forces) The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe Shadowland by Peter Straub Best Short Fiction: “Cabin 33” by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (in Shadows 3) “Children of the Kingdom” by T.E.D. Klein (in Dark Forces) “The Ugly Chickens” by Howard Waldrop (in Universe 10) “Unicorn Tapestry” by Suzy McKee Charnas (in New Dimensions 11) Best Anthology or Collection: Dark Forces ed. by Kirby McCauley Dragons of Light ed. by Orson Scott Card Mummy! A Chrestomathy of Crypt-ology ed. by Bill Pronzini New Terrors 1 ed. by Ramsey Campbell Shadows 3 ed. by Charles L. Grant Shatterday by Harlan Ellison Best Artist: Alicia Austin Thomas Canty Don Maitz Rowena Morrill Michael Whelan Gahan Wilson Special Award (Professional) Terry Carr (anthologist) Lester del Rey (Del Rey/Ballantine Books) Edward L. Ferman (Magazine of Fantasy ir Science Fiction) David G. Hartwell (Pocket/Timescape/Simon & Schuster) Tim Underwood/Chuck Miller (Underwood & Miller) Donald A. Wollheim (DAW Books) Special Award (Non-professional) Pat Cadigan/Arnie Fenner (for Shayol) Charles de Lint/Charles R. -

Language & the Mind LING240 Summer Session II 2005 Creativity of Human Language Linguistic Creativity an Account That Won'

Creativity of Human Language Language & the Mind LING240 • Ability to combine signs with simple meanings to create utterances with Summer Session II 2005 complex meanings • Novel expressions Lecture 3 • Infinitely many Sentences Linguistic Creativity An Account That Won’t Work • Sentences never heard before... • “You just string words together in an – “Some purple tulips are starting to samba on the chessboard.” order that makes sense” • Sentences of prodigious length... – “Hoggle said that he thought that the odiferous in other words... leader of the goblins had it in mind to tell the unfortunate princess that the cries that she made during her kidnapping from the nearby kingdom of Dirindwell that the goblins “Syntax is determined by Meaning” themselves thought was a general waste of countryside ...” Syntax is More than Meaning Syntax is More than Meaning • Nonsense sentences with clear syntax • Nonsense sentences with clear syntax ‘Twas brillig and the slithy toves Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. (Chomsky) Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; A verb crumpled the ocean. All mimsy were the borogroves, And the mome raths outgrabe I gave the question a goblin-shimmying egg. Beware the Jabberwock, my son! The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! *Furiously sleep ideas green colorless. Beware the Jujub bird, and shun Ocean the crumpled verb a. The frumious Bandersnatch!” *The question I an egg goblin-shimmying gave. Lewis Carroll, Jabberwocky 1 Syntax is More than Meaning Syntax is More than Meaning 'It seems very pretty,' she said when • Nonsense sentences with nonsense syntax she had finished it, 'but it's RATHER hard to understand!' (You see she ‘Toves slithy the and brillig ‘twas didn't like to confess, ever to wabe the in gimble and gyre did.. -

La Exposición Sobre Jim Henson Una Imaginación Sin Límites

SE RUEGA NO SACAR DE LA GALERÍA La exposición sobre Jim Henson una imaginación sin límites AN EXHIBITION ORGANIZED BY ©MUPPETS/DISNEY. ©2019 SESAME WORKSHOP. ©THE JIM HENSON COMPANY. SE RUEGA NO SACAR DE LA GALERÍA 1. Proyección LA EXPOSICIÓN SOBRE JIM HENSON: UNA IMAGINACIÓN SIN LÍMITES A lo largo de su singular carrera que se extendió a lo largo de cuatro décadas, Jim Henson creó personajes de marionetas e historias que se convirtieron en iconos del cine y la televisión y han dejado una marca indeleble en la cultura popular. Con su sentido del humor delicadamente subversivo, su infatigable curiosidad y su mirada innovadora sobre el arte de las marionetas, Henson creó los Muppets/Teleñecos y los convirtió en una marca internacional perdurable, nos regaló los adorables personajes de Plaza/Barrio Sésamo y plasmó su rica imaginación en películas e historias para la gran pantalla. En esta exposición indagamos en las extraordinarias aportaciones con las que Jim Henson contribuyó al campo de la imagen en movimiento y desvelamos cómo él y su talentoso equipo de diseñadores, actores y escritores crearon una obra sin parangón que hoy día sigue inspirando y deleitando a personas de todas las edades. 2. Jim Henson y la rana René/Gustavo en el set de Llegan los Muppets/La película de los Teleñecos (1978) 3. Marioneta de la rana René/Gustavo, hacia 1978 Diseñada por Jim Henson Confeccionada por Caroly Wilcox a partir de patrones diseñados por Don Sahlin Manejada por Jim Henson Tela de vellón, fieltro, plástico, caucho y papel autoadhesivo de vinilo Cedido en préstamo por la familia de Jim Henson (Jim Henson confeccionó la primera marioneta de la rana René/Gustavo en 1955). -

ITALIAN BOWIE Tutto Di David Bowie in Italia E Visto Dall'italia INTRODUZIONE

Davide Riccio ITALIAN BOWIE Tutto di David Bowie in Italia e visto dall'Italia INTRODUZIONE Bowie ascoltava la musica italiana? Ogni nazione avrebbe voluto avere i propri Elvis, i propri Beatles, i propri Rolling Stones, il proprio Bob Dylan o il proprio "dio del rock" David Bowie, giusto per fare qualche nome: fare cioè propri i più grandi tra i grandi della storia del rock. O incoronarne in patria un degno corrispettivo. I paesi che non siano britannici o statunitensi perciò di loro lingua franca mondiale sono tuttavia fuori dal gioco: il rock è innanzi tutto un fatto di lingua inglese. Non basta evidentemente cantare in inglese senza essere inglesi, irlandesi o statunitensi et similia per uguagliare in popolarità internazionale gli originari o gli oriundi ed entrare di diritto nella storia internazionale del rock. A volte poi, pur appartenendo alla stessa lingua inglese, il cercarne o crearne un corrispettivo è operazione comunque inutile ai fini del fare o non fare la storia del rock, oltre che un fatto assai discutibile, così come avvenne a esempio negli States in piena Beatlemania con i Monkees, giusto per citare un gruppo nel quale cantava un certo David o Davy Jones, lo stesso che - per evitare omonimia e confusione - portò David Robert Jones, ispirandosi al soldato Jim Bowie e al suo particolare coltello, il cosiddetto Bowie knife, ad attribuirsi un nome d'arte: David Bowie. I Monkees nacquero nel 1965 su idea del produttore discografico Don Kirshner per essere la risposta rivale (anzitutto commerciale) americana ai Beatles, quindi i Beatles americani o gli anti-Beatles.