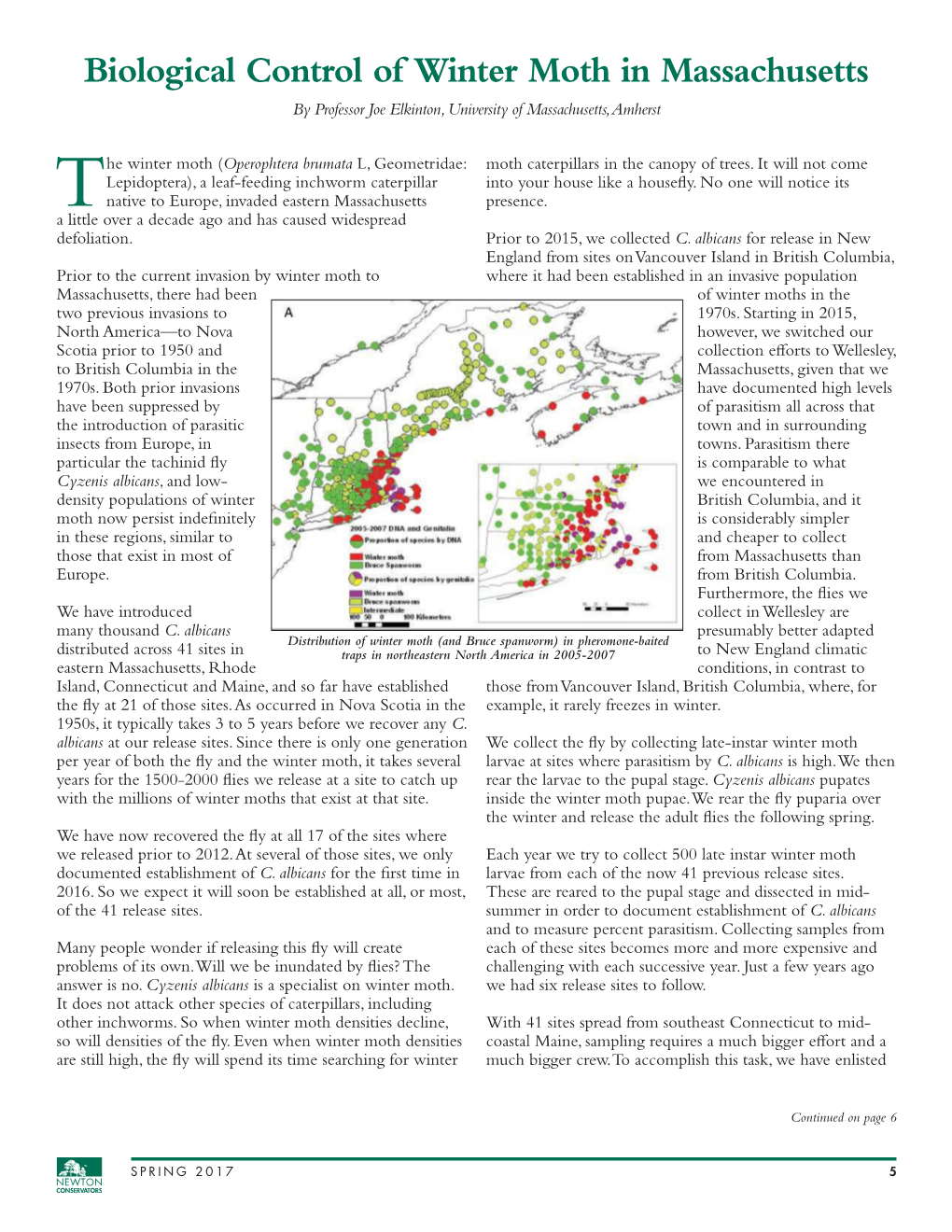

Biological Control of Winter Moth in Massachusetts by Professor Joe Elkinton, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Softwood Insect Pests

Forest & Shade Tree Insect & Disease Conditions for Maine A Summary of the 2011 Situation Forest Health & Monitoring Division Maine Forest Service Summary Report No. 23 MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION March 2012 Augusta, Maine Forest Insect & Disease—Advice and Technical Assistance Maine Department of Conservation, Maine Forest Service Insect and Disease Laboratory 168 State House Station, 50 Hospital Street, Augusta, Maine 04333-0168 phone (207) 287-2431 fax (207) 287-2432 http://www.maine.gov/doc/mfs/idmhome.htm The Maine Forest Service/Forest Health and Monitoring (FH&M) Division maintains a diagnostic laboratory staffed with forest entomologists and a forest pathologist. The staff can provide practical information on a wide variety of forest and shade tree problems for Maine residents. Our technical reference library and insect collection enables the staff to accurately identify most causal agents. Our website is a portal to not only our material and notices of current forest pest issues but also provides links to other resources. A stock of information sheets and brochures is available on many of the more common insect and disease problems. We can also provide you with a variety of useful publications on topics related to forest insects and diseases. Submitting Samples - Samples brought or sent in for diagnosis should be accompanied by as much information as possible including: host plant, type of damage (i.e., canker, defoliation, wilting, wood borer, etc.), date, location, and site description along with your name, mailing address and day-time telephone number or e-mail address. Forms are available (on our Web site and on the following page) for this purpose. -

No Slide Title

Tachinidae: The “other” parasitoids Diego Inclán University of Padova Outline • Briefly (re-) introduce parasitoids & the parasitoid lifestyle • Quick survey of dipteran parasitoids • Introduce you to tachinid flies • major groups • oviposition strategies • host associations • host range… • Discuss role of tachinids in biological control Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Life cycle of a parasitoid Alien (1979) Life cycle of a parasitoid Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Parasitoid does not kill the host kill its host Insects life cycles Life cycle of a parasitoid Some facts about parasitoids • Parasitoids are diverse (15-25% of all insect species) • Hosts of parasitoids = virtually all terrestrial insects • Parasitoids are among the dominant natural enemies of phytophagous insects (e.g., crop pests) • Offer model systems for understanding community structure, coevolution & evolutionary diversification Distribution/frequency of parasitoids among insect orders Primary groups of parasitoids Diptera (flies) ca. 20% of parasitoids Hymenoptera (wasps) ca. 70% of parasitoids Described Family Primary hosts Diptera parasitoid sp Sciomyzidae 200? Gastropods: (snails/slugs) Nemestrinidae 300 Orth.: Acrididae Bombyliidae 5000 primarily Hym., Col., Dip. Pipunculidae 1000 Hom.:Auchenorrycha Conopidae 800 Hym:Aculeata Lep., Orth., Hom., Col., Sarcophagidae 1250? Gastropoda + others Lep., Hym., Col., Hem., Tachinidae > 8500 Dip., + many others Pyrgotidae 350 Col:Scarabaeidae Acroceridae 500 Arach.:Aranea Hym., Dip., Col., Lep., Phoridae 400?? Isop.,Diplopoda -

The Winter Moth ( Operophtera Brumata) and Its Natural Enemies in Orkney

Spatial ecology of an insect host-parasitoid-virus interaction: the winter moth ( Operophtera brumata) and its natural enemies in Orkney Simon Harold Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Biological Sciences September 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ©2009 The University of Leeds and Simon Harold ii Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge the support of my supervisors Steve Sait and Rosie Hails for their continued advice and support throughout the duration of the project. I particularly thank Steve for his patience, enthusiasm, and good humour over the four years—and especially for getting work back to me so quickly, more often than not because I had sent it at the eleventh hour. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Earth and Biosphere Institute (EBI) at the University of Leeds for funding this project in the first instance. Steve Carver also helped secure funding. The molecular work was additionally funded by both a NERC short-term grant, and funding from UKPOPNET, to whom I am also grateful. None of the fieldwork, and indeed the scope and scale of the project, would have been possible if not for the stellar cast of fieldworkers that made the journey to Orkney. They were (in order of appearance): Steve Sait, Rosie Hails, Jackie Osbourne, Bill Tyne, Cathy Fiedler, Ed Jones, Mike Boots, Sandra Brand, Shaun Dowman, Rachael Simister, Alan Reynolds, Kim Hutchings, James Rosindell, Rob Brown, Catherine Bourne, Audrey Zannesse, Leo Graves and Steven White. -

Influence of Habitat and Bat Activity on Moth Community Composition and Seasonal Phenology Across Habitat Types

INFLUENCE OF HABITAT AND BAT ACTIVITY ON MOTH COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND SEASONAL PHENOLOGY ACROSS HABITAT TYPES BY MATTHEW SAFFORD THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Advisor: Assistant Professor Alexandra Harmon-Threatt, Chair and Director of Research ABSTRACT Understanding the factors that influence moth diversity and abundance is important for monitoring moth biodiversity and developing conservation strategies. Studies of moth habitat use have primarily focused on access to host plants used by specific moth species. How vegetation structure influences moth communities within and between habitats and mediates the activity of insectivorous bats is understudied. Previous research into the impact of bat activity on moths has primarily focused on interactions in a single habitat type or a single moth species of interest, leaving a large knowledge gap on how habitat structure and bat activity influence the composition of moth communities across habitat types. I conducted monthly surveys at sites in two habitat types, restoration prairie and forest. Moths were collected using black light bucket traps and identified to species. Bat echolocation calls were recorded using ultrasonic detectors and classified into phonic groups to understand how moth community responds to the presence of these predators. Plant diversity and habitat structure variables, including tree diameter at breast height, ground cover, and vegetation height were measured during summer surveys to document how differences in habitat structure between and within habitats influences moth diversity. I found that moth communities vary significantly between habitat types. -

Lateinischer Tiernamen. Anonymus

A Index lateinischer Tiernamen Die AutorennameaSubgenus- und Subspeziesbezeichnungen sind dem Textteil zu entnehmen! Abdera 71 Alburnus alburnus 54, 56 Aporia crataegi 102 Abramis brama 53 - bipunctatus 56 Aporophila lutulenta 108 Abraxas grossulariata 111 Alcedo atthis 44 Aquila chrysaetos 44 Acanthocinus griseus 84 Alcis jubata 112 - clanga 46 - reticulatus 84 Alectoris graeca 43 - heliaca 46 Acasis appensata 123 Allophyes oxyacanthae 109 - pomarina 46 - viretata 112 Aiosa aiosa 53 Araschnia levana 104 Accipiter gentilis 44 Alsophila quadripunctaria 112 Archanara geminipuncta 119 - nisus 44 Amata phegea 107 - neurica 108 Acipenser ruthenus 51, 53, 56 Amathes castanea 108 - sparganii 109 - güldenstädti51,53 - collina 110 Arctaphaenops nihilumalbi 77 Acmaeodera degener 86 Ampedus 68 - styriacus 63, 77 Acmaeoderella ftavofasciata 85 Amphibia 49-50 Arctinia caesarea 117 Acmaeops marginata 79 Amphipoea fucosa 109 Ardea cinerea 44 - pratensis 84 Amphipyra livida 109 - purpurea 43, 46 - septentrionis 84 - tetra 109 Ardeola ralloides 46 Acontia luctuosa 109 Anaesthetis testacea 82 Argante herbsti 86 Acrocephalus schoenobaenus 45 Anaitis efformata 111 Argiope bruenichi 16 Acroloxus lacustris 144 Anarta cordigera 110 Argna biplicata 141,145 Actia infantula 131 - myrtilli 108 Aricia artaxerxes 104 - pilipennis 131 Anas crecca 44 Arion alpinus 141 Actinotia hyperici 108 - querquedula 44 - lusitanicus 141 Actitis hypoleucos 44 Anax parthenope 60 - ruf us 141 Adelocera 68 Ancylus fluviatilis 139, 144 Aromia moschata 82 Admontia blanda 131 Anemadus -

Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | Umass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment

5/24/2019 Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | UMass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Apply Give Search (/) LNUF Home (/landscape) About (/landscape/about) Newsletters & Updates (/landscape/newsletters-updates) Publications & Resources (/landscape/publications-resources) Services (/landscape/services) Education & Events (/landscape/upcoming-events) Make a Gift (https://securelb.imodules.com/s/1640/alumni/index.aspx? sid=1640&gid=2&pgid=443&cid=1121&dids=2540) (/landscape) Search the Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Search this site Search Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 May 24, 2019 Issue: 9 UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data. The Landscape Message will be updated weekly in May and June. The next message will be posted on May 31. To receive immediate notication when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list (/landscape/email-list). To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content: Scouting Information by Region ag.umass.edu/landscape/landscape-message-may-24-2019 1/18 5/24/2019 Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | UMass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Environmental Data The following data was collected on or about May 22, 2019. -

Local Outbreaks of Operophtera Brumata and Operophtera Fagata Cannot Be Explained by Low Vulnerability to Pupal Predation

Postprint version. Original publication in: Agricultural and Forest Entomology (2010) 12(1): 81-87 doi: 10.1111/j.1461-9563.2009.00455.x Local outbreaks of Operophtera brumata and Operophtera fagata cannot be explained by low vulnerability to pupal predation Annette Heisswolf, Miia Käär, Tero Klemola, Kai Ruohomäki Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland Abstract. One of the unresolved questions in studies on population dynamics of for- est Lepidoptera is why some populations at times reach outbreak densities, whereas oth- ers never do. Resolving this question is especially challenging if populations of the same species in different areas or of closely-related species in the same area are considered. The present study focused on three closely-related geometrid moth species, autumnal Epirrita autumnata, winter Operophtera brumata and northern winter moths Operophtera fagata, in southern Finland. There, winter and northern winter moth populations can reach outbreak densities, whereas autumnal moth densities stay relatively low. We tested the hypothesis that a lower vulnerability to pupal predation may explain the observed differences in population dynamics. The results obtained do not support this hypothesis because pupal predation probabilities were not significantly different between the two genera within or without the Operophtera outbreak area or in years with or without a current Operophtera outbreak. Overall, pupal predation was even higher in winter and northern winter moths than in autumnal moths. Differences in larval predation and parasitism, as well as in the repro- ductive capacities of the species, might be other candidates. Keywords. Epirrita autumnata; forest Lepidoptera; Operophtera brumata; Operoph- tera fagata; outbreak; population dynamics; pupal predation. -

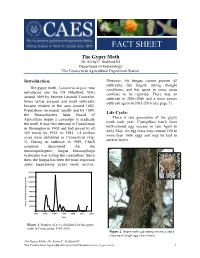

The Gypsy Moth Dr

FACT SHEET The Gypsy Moth Dr. Kirby C. Stafford III Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Introduction: However, the fungus cannot prevent all outbreaks, due largely during drought The gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, was conditions, and hot spots in some areas introduced into the US (Medford, MA) continue to be reported. There was an around 1869 by Etienne Leopold Trouvelot. outbreak in 2005-2006 and a more severe Some larvae escaped and small outbreaks outbreak again in 2015-2016 (see page 7). became evident in the area around 1882. Populations increased rapidly and by 1889, the Massachusetts State Board of Life Cycle: Agriculture began a campaign to eradicate There is one generation of the gypsy the moth. It was first detected in Connecticut moth each year. Caterpillars hatch from in Stonington in 1905 and had spread to all buff-colored egg masses in late April to 169 towns by 1952. In 1981, 1.5 million early May. An egg mass may contain 100 to acres were defoliated in Connecticut (Fig. more than 1000 eggs and may be laid in 1). During an outbreak in 1989, CAES several layers. scientists discovered that the entomopathogenic fungus Entomophaga maimaiga was killing the caterpillars. Since then, the fungus has been the most important agent suppressing gypsy moth activity. 1600000 1400000 1200000 1000000 800000 600000 400000 Acres defoliation bygypsy moth defoliation Acres 200000 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Year Figure 1. Number of acres defoliated by the gypsy moth in Connecticut, 1969-2016. Figure 2. Gypsy moth egg masses on a tree and a close-up of single egg mass (inset). -

Identification of Winter Moth (Operophtera Brumata) Refugia in North Africa and the Italian Peninsula During the Last Glacial Maximum

Received: 1 October 2019 | Accepted: 14 October 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.5830 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Identification of winter moth (Operophtera brumata) refugia in North Africa and the Italian Peninsula during the last glacial maximum Jeremy C. Andersen1 | Nathan P. Havill2 | Yaussra Mannai3 | Olfa Ezzine4 | Samir Dhahri3 | Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa3 | Adalgisa Caccone5 | Joseph S. Elkinton1 1Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Abstract Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA Numerous studies have shown that the genetic diversity of species inhabiting 2 Northern Research Station, USDA Forest temperate regions has been shaped by changes in their distributions during the Service, Hamden, CT, USA 3LR161INRGREF01 Laboratory of Quaternary climatic oscillations. For some species, the genetic distinctness of iso- Management and Valorization of Forest lated populations is maintained during secondary contact, while for others, admix- Resources, National Institute for Research in Rural Engineering Water and Forest ture is frequently observed. For the winter moth (Operophtera brumata), an important (INRGREF), University of Carthage, Ariana, defoliator of oak forests across Europe and northern Africa, we previously deter- Tunisia mined that contemporary populations correspond to genetic diversity obtained dur- 4LR161INRGREF03 Laboratory of Forest Ecology, National Institute for Research ing the last glacial maximum (LGM) through the use of refugia in the Iberian and in Rural Engineering Water and Forest Aegean peninsulas, and to a lesser -

The Relationship Between the Winter Moth (Operophtera Brumata) and Its Host Plants in Coastal Maine Kaitlyn M

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-2015 The Relationship Between the Winter Moth (Operophtera brumata) and Its Host Plants in Coastal Maine Kaitlyn M. O'Donnell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, and the Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation O'Donnell, Kaitlyn M., "The Relationship Between the Winter Moth (Operophtera brumata) and Its Host Plants in Coastal Maine" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2338. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2338 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE WINTER MOTH (OPEROPTHERA BRUMATA) AND ITS HOST PLANTS IN COASTAL MAINE By Kaitlyn O’Donnell B.S. Saint Michael’s College, 2011 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Entomology) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2015 Advisory Committee: Eleanor Groden, Professor of Entomology, School of Biology and Ecology, Advisor Francis Drummond, Professor of Insect Ecology and Wild Blueberry Pest Management Specialist, School of Biology and Ecology and the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Joseph Elkinton, Professor of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Charlene Donahue, Forest Entomologist, Maine Forest Service THESIS ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Kaitlyn O’Donnell I affirm that this manuscript is the final and accepted thesis. -

10 Winter Moth (Operophtera Brumata)

Brighton & Hove City Council Arboricultural Information Note No. 10 Winter Moth (Operophtera brumata) Winter moth is aptly named: the adults emerge from November to mid-January. It is one of several moths that are active during the autumn to spring period. In many of these ‘cold weather’ moths, the two sexes are quite different. Males have fully developed wings (above) and a typical moth-like appearance, but the females (left) are either wingless or have greatly reduced wings, making them incapable of flight. Winter moths emerge on mild evenings from pupae in the soil. While the drab, greyish-brown males can fly about, the females have to crawl up the trunks and along the branches of trees until they reach the twiggy shoots where they mate and lay their eggs. These eggs hatch in spring when the trees come into leaf. Many deciduous trees and shrubs, including oak, hornbeam, lime, sycamore, mountain ash, birch, rose, apple, plum, pear and cherry are host plants. The caterpillars are up to 20mm long and pale green with stripes along their bodies. Winter moth caterpillars can be so abundant on oak trees that, in combination with other moth caterpillars, they cause severe defoliation in spring. The trees survive, producing new leaves in early summer as caterpillars are fully fed by late May or early June, when they move down into the soil to pupate. Protecting trees Winter moths can damage garden trees, especially fruit trees. Fruit growers can protect these by placing sticky grease bands on the trunks in late October. This forms a barrier against the crawling females and reduces the number of eggs laid on the twigs. -

2017 Winter Moth Caterpillar Update

T O W N O F W E L L E S L E Y M A S S A C H U S E T T S DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS PARK & TREE DIVISION 30 MUNICIPAL WAY WELLESLEY, MA 02481-4925 MICHAEL T. QUINN TELEPHONE (781) 235-7600 ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENT EXT. 3331 DEPUTY TREE WARDEN FACSIMILE (781) 431-7569 WWW. WELLESLEYMA.GOV [email protected] 2017 Winter Moth Caterpillar Update In Wellesley and throughout eastern Massachusetts the winter moth caterpillar has been defoliating trees during the spring. Under the authority of the Natural Resources Commission and the guidelines of the Wellesley Integrated Pest Management Policy, the Department of Public Works will be deferring the ground spraying town trees to control winter moth caterpillars, unless an identified tree is determined in need of spraying in order to survive. These exceptions will be treated with Conserve #SC, a spinosad based product, E.P.A. Reg. #62719-291. Hours of spraying will occur between 5am thru 10 am. and will not occur after May 30th, 2016. All treated areas will be posted for 24 hours before and after applications. This is the same strategy we applied in 2014, 2015 AND 2016. During those years we found no trees in need of spraying. The reason for this strategy is due to a team of scientists led by Joseph Elkinton at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This team released approximately 1,000 parasitic flies at Centennial Park in Wellesley on May 9th, 2008, to help biologically control this invasive caterpillar. In eastern Massachusetts this caterpillar has been stripping the foliage from many kinds of deciduous trees in towns that stretch from the North Shore to Cape Cod.