Winter Moth Time by Matt Bowser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Climate Change Impacts Report Card Technical Paper 12. the Impact of Climate Change on Biological Phenology In

Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Biodiversity Climate Change impacts report card technical paper 12. The impact of climate change on biological phenology in the UK Tim Sparks1 & Humphrey Crick2 1 Faculty of Engineering and Computing, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, CV1 5FB 2 Natural England, Eastbrook, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge, CB2 8DR Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Executive summary Phenology can be described as the study of the timing of recurring natural events. The UK has a long history of phenological recording, particularly of first and last dates, but systematic national recording schemes are able to provide information on the distributions of events. The majority of data concern spring phenology, autumn phenology is relatively under-recorded. The UK is not usually water-limited in spring and therefore the major driver of the timing of life cycles (phenology) in the UK is temperature [H]. Phenological responses to temperature vary between species [H] but climate change remains the major driver of changed phenology [M]. For some species, other factors may also be important, such as soil biota, nutrients and daylength [M]. Wherever data is collected the majority of evidence suggests that spring events have advanced [H]. Thus, data show advances in the timing of bird spring migration [H], short distance migrants responding more than long-distance migrants [H], of egg laying in birds [H], in the flowering and leafing of plants[H] (although annual species may be more responsive than perennial species [L]), in the emergence dates of various invertebrates (butterflies [H], moths [M], aphids [H], dragonflies [M], hoverflies [L], carabid beetles [M]), in the migration [M] and breeding [M] of amphibians, in the fruiting of spring fungi [M], in freshwater fish migration [L] and spawning [L], in freshwater plankton [M], in the breeding activity among ruminant mammals [L] and the questing behaviour of ticks [L]. -

Softwood Insect Pests

Forest & Shade Tree Insect & Disease Conditions for Maine A Summary of the 2011 Situation Forest Health & Monitoring Division Maine Forest Service Summary Report No. 23 MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION March 2012 Augusta, Maine Forest Insect & Disease—Advice and Technical Assistance Maine Department of Conservation, Maine Forest Service Insect and Disease Laboratory 168 State House Station, 50 Hospital Street, Augusta, Maine 04333-0168 phone (207) 287-2431 fax (207) 287-2432 http://www.maine.gov/doc/mfs/idmhome.htm The Maine Forest Service/Forest Health and Monitoring (FH&M) Division maintains a diagnostic laboratory staffed with forest entomologists and a forest pathologist. The staff can provide practical information on a wide variety of forest and shade tree problems for Maine residents. Our technical reference library and insect collection enables the staff to accurately identify most causal agents. Our website is a portal to not only our material and notices of current forest pest issues but also provides links to other resources. A stock of information sheets and brochures is available on many of the more common insect and disease problems. We can also provide you with a variety of useful publications on topics related to forest insects and diseases. Submitting Samples - Samples brought or sent in for diagnosis should be accompanied by as much information as possible including: host plant, type of damage (i.e., canker, defoliation, wilting, wood borer, etc.), date, location, and site description along with your name, mailing address and day-time telephone number or e-mail address. Forms are available (on our Web site and on the following page) for this purpose. -

The Winter Moth ( Operophtera Brumata) and Its Natural Enemies in Orkney

Spatial ecology of an insect host-parasitoid-virus interaction: the winter moth ( Operophtera brumata) and its natural enemies in Orkney Simon Harold Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Biological Sciences September 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ©2009 The University of Leeds and Simon Harold ii Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge the support of my supervisors Steve Sait and Rosie Hails for their continued advice and support throughout the duration of the project. I particularly thank Steve for his patience, enthusiasm, and good humour over the four years—and especially for getting work back to me so quickly, more often than not because I had sent it at the eleventh hour. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Earth and Biosphere Institute (EBI) at the University of Leeds for funding this project in the first instance. Steve Carver also helped secure funding. The molecular work was additionally funded by both a NERC short-term grant, and funding from UKPOPNET, to whom I am also grateful. None of the fieldwork, and indeed the scope and scale of the project, would have been possible if not for the stellar cast of fieldworkers that made the journey to Orkney. They were (in order of appearance): Steve Sait, Rosie Hails, Jackie Osbourne, Bill Tyne, Cathy Fiedler, Ed Jones, Mike Boots, Sandra Brand, Shaun Dowman, Rachael Simister, Alan Reynolds, Kim Hutchings, James Rosindell, Rob Brown, Catherine Bourne, Audrey Zannesse, Leo Graves and Steven White. -

Predicting the Invasion Range for a Highly Polyphagous And

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 59: 1–20 (2020) Winter moth environmental niche 1 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.59.53550 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions Predicting the invasion range for a highly polyphagous and widespread forest herbivore Laura M. Blackburn1, Joseph S. Elkinton2, Nathan P. Havill3, Hannah J. Broadley2, Jeremy C. Andersen2, Andrew М. Liebhold1,4 1 Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA 2 Department of En- vironmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA 3 Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Hamden, Connecticut, USA 4 Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, 165 00 Praha 6 – Suchdol, Czech Republic Corresponding author: Andrew Liebhold ([email protected]) Academic editor: Ingolf Kühn | Received 23 April 2020 | Accepted 26 June 2020 | Published 28 July 2020 Citation: Blackburn LM, Elkinton JS, Havill NP, Broadley HJ, Andersen JC, Liebhold AМ (2020) Predicting the invasion range for a highly polyphagous and widespread forest herbivore. NeoBiota 59: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3897/ neobiota.59.53550 Abstract Here we compare the environmental niche of a highly polyphagous forest Lepidoptera species, the winter moth (Operophtera brumata), in its native and invaded range. During the last 90 years, this European tree fo- livore has invaded North America in at least three regions and exhibited eruptive population behavior in both its native and invaded range. Despite its importance as both a forest and agricultural pest, neither the poten- tial extent of this species’ invaded range nor the geographic source of invading populations from its native range are known. -

Influence of Habitat and Bat Activity on Moth Community Composition and Seasonal Phenology Across Habitat Types

INFLUENCE OF HABITAT AND BAT ACTIVITY ON MOTH COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND SEASONAL PHENOLOGY ACROSS HABITAT TYPES BY MATTHEW SAFFORD THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Advisor: Assistant Professor Alexandra Harmon-Threatt, Chair and Director of Research ABSTRACT Understanding the factors that influence moth diversity and abundance is important for monitoring moth biodiversity and developing conservation strategies. Studies of moth habitat use have primarily focused on access to host plants used by specific moth species. How vegetation structure influences moth communities within and between habitats and mediates the activity of insectivorous bats is understudied. Previous research into the impact of bat activity on moths has primarily focused on interactions in a single habitat type or a single moth species of interest, leaving a large knowledge gap on how habitat structure and bat activity influence the composition of moth communities across habitat types. I conducted monthly surveys at sites in two habitat types, restoration prairie and forest. Moths were collected using black light bucket traps and identified to species. Bat echolocation calls were recorded using ultrasonic detectors and classified into phonic groups to understand how moth community responds to the presence of these predators. Plant diversity and habitat structure variables, including tree diameter at breast height, ground cover, and vegetation height were measured during summer surveys to document how differences in habitat structure between and within habitats influences moth diversity. I found that moth communities vary significantly between habitat types. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of the Tribe Operophterini (Lepidoptera, Geometridae): a Case Study of the Evolution of Female flightlessness

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 92, 241–252. With 1 figure Phylogenetic relationships of the tribe Operophterini (Lepidoptera, Geometridae): a case study of the evolution of female flightlessness NIINA SNÄLL1,2, TOOMAS TAMMARU4*, NIKLAS WAHLBERG1,5, JAAN VIIDALEPP6, KAI RUOHOMÄKI2, MARJA-LIISA SAVONTAUS1 and KIRSI HUOPONEN3 1Laboratory of Genetics, Department of Biology, 2Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, and 3Department of Medical Genetics, University of Turku, FIN-20014 Turku, Finland 4Institute of Zoology and Hydrobiology, University of Tartu, Vanemuise 46, EE-51014 Tartu, Estonia 5Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 6Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Kreutzwaldi 64, EE-51014 Tartu, Estonia Received 24 April 2006; accepted for publication 20 November 2006 A molecular phylogenetic analysis was conducted in order to reconstruct the evolution of female flightlessness in the geometrid tribe Operophterini (Lepidoptera, Geometridae, Larentiinae). DNA variation in four nuclear gene regions, segments D1 and D2 of 28S rRNA, elongation factor 1a, and wingless, was examined from 22 species representing seven tribes of Larentiinae and six outgroup species. Direct optimization was used to infer a phylogenetic hypothesis from the combined sequence data set. The results obtained confirmed that Operophterini (including Malacodea) is a monophyletic group, and Perizomini is its sister group. Within Operophterini, the genus Malacodea is the sister group to the genera Operophtera and Epirrita, which form a monophyletic group. This relationship is also supported by morphological data. The results suggest that female flightlessness has evolved independently twice: first in the lineage of Malacodea and, for the second time, in the lineage of Operophtera after its separation from the lineage of Epirrita. -

ABHANDLUNGEN Aus Dem Westfälischen Museum Für Naturkunde - Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe

ISS N 0023 - 7906 ABHANDLUNGEN aus dem Westfälischen Museum für Naturkunde - Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe - herausgegeben von P r o f. D r. L. F R A N Z I S K E T Direktor des Westfälischen Museums für Naturkunde, Münster 44. JAHRGANG 1982, HEFT 1 Lepidoptera Westfalica HANS-JOACHIM WEIGT, Unna Westfälische Ve r eindruckerei 4 4 00 Münster Die Abhandlungen aus dem Westfälischen Museum für Naturkunde bringen wi ssenschaftliche Beiträge zur Erforschung des Naturraumes Westfalen. Die Autoren werden gebeten, die Manuskripte in Maschinenschrift (1 112 Zeilen Abstand) druckfertig einzusenden an: Westfälisches Museum für Naturkunde Schriftleitung Abhandlungen, Dr. Brunhild Gries Sentruper Straße 285, 4400 MÜNSTER Lateinische Art- und Rassennamen sind fü r den Kursivdruck mit einer Wellen linie zu unterschlängeln; Wörter, di e in Sperrdruck hervorgehoben werden sollen, sind m it Bleistift mit ei ner unterbrochenen Linie zu unterstreichen. Autorennamen sind in Großbuchstaben zu schreiben. Abschnitte, die in Kl eindruck gebracht wer den kö nnen, sind am linken Rand mit „petit" zu bezeichnen. Abbildungen (Karten, Zeichnungen, Fotos) sollen ni cht direkt, sondern auf einem transparenten mit einem Falz angeklebten Deckblatt beschriftet werden. Unsere Grafikerin über• trägt Ihre Vorlage in das Original. Abbildungen werden nur aufgenommen, wenn sie bei Verkleinerung auf Satzspiegelbreite (12 ,5 cm) noch gut lesbar sind. Die Herstellung größerer Abbildungen kann wegen der Kosten nur in solchen Fällen erfolgen, in denen grafische Darstellungen einen entscheidenden Beitrag der Arbeit ausmachen. Das Literaturverzeichnis ist nach folgendem Muster anzufertigen: BUDDE, H. & W. BROCKHAUS (1954): Die Vegetation des westfälischen Berglandes. - Decheniana 102, 47-275. KRAMER, H. (1962): Zum Vorkom men des Fischreihers in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. -

Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | Umass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment

5/24/2019 Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | UMass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Apply Give Search (/) LNUF Home (/landscape) About (/landscape/about) Newsletters & Updates (/landscape/newsletters-updates) Publications & Resources (/landscape/publications-resources) Services (/landscape/services) Education & Events (/landscape/upcoming-events) Make a Gift (https://securelb.imodules.com/s/1640/alumni/index.aspx? sid=1640&gid=2&pgid=443&cid=1121&dids=2540) (/landscape) Search the Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Search this site Search Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 May 24, 2019 Issue: 9 UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data. The Landscape Message will be updated weekly in May and June. The next message will be posted on May 31. To receive immediate notication when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list (/landscape/email-list). To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content: Scouting Information by Region ag.umass.edu/landscape/landscape-message-may-24-2019 1/18 5/24/2019 Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | UMass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Environmental Data The following data was collected on or about May 22, 2019. -

Local Outbreaks of Operophtera Brumata and Operophtera Fagata Cannot Be Explained by Low Vulnerability to Pupal Predation

Postprint version. Original publication in: Agricultural and Forest Entomology (2010) 12(1): 81-87 doi: 10.1111/j.1461-9563.2009.00455.x Local outbreaks of Operophtera brumata and Operophtera fagata cannot be explained by low vulnerability to pupal predation Annette Heisswolf, Miia Käär, Tero Klemola, Kai Ruohomäki Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland Abstract. One of the unresolved questions in studies on population dynamics of for- est Lepidoptera is why some populations at times reach outbreak densities, whereas oth- ers never do. Resolving this question is especially challenging if populations of the same species in different areas or of closely-related species in the same area are considered. The present study focused on three closely-related geometrid moth species, autumnal Epirrita autumnata, winter Operophtera brumata and northern winter moths Operophtera fagata, in southern Finland. There, winter and northern winter moth populations can reach outbreak densities, whereas autumnal moth densities stay relatively low. We tested the hypothesis that a lower vulnerability to pupal predation may explain the observed differences in population dynamics. The results obtained do not support this hypothesis because pupal predation probabilities were not significantly different between the two genera within or without the Operophtera outbreak area or in years with or without a current Operophtera outbreak. Overall, pupal predation was even higher in winter and northern winter moths than in autumnal moths. Differences in larval predation and parasitism, as well as in the repro- ductive capacities of the species, might be other candidates. Keywords. Epirrita autumnata; forest Lepidoptera; Operophtera brumata; Operoph- tera fagata; outbreak; population dynamics; pupal predation. -

Plant Invasions in Rhode Island Riparian Zones ✴Paleostratigraphy in B Y S U Z a N N E M

Volume 12 • Number 2 • November 2005 What’s Inside… Plant Invasions in Rhode Island Riparian Zones ✴Paleostratigraphy in B Y S U Z A N N E M . L U S S I E R A N D S A R A N . D A S I L V A the Campus Freezer ✴Wandering Hooded Riparian zones opportunistic, they are often the first Methods Seals are the corridors plants to colonize disturbed patches of Selecting the Study Sites ✴Bringing Watershed of land adjacent soil and forest edges. Several research- Health and Land to streams, riv- ers have found that riparian zones sup- By using hydrographical and land Use History into the use/land cover data from the Rhode Classroom ers, and other port a greater abundance and diversity Island Geographic Information System ✴ surface waters, of invasive plants than other habitats The Paleozoology (RIGIS, http://www.edc.uri.edu/rigis/), Collection of the which serve as (Brown and Peet 2003, Burke and Museum of Natural transitional areas Grime 1996, Gregory et al. 1991). we characterized eight subwatersheds History, Roger Wil- between terres- by their percentage of residential land liams Park trial and aquatic Streams within urban and suburban use (4–59%). Stream corridors were de- ✴“The Invasives Beat” systems. Their watersheds characteristically carry lineated using orthophotos and verified ✴Bioblitz 2005 vegetation pro- higher nutrient loads following storm with on-site latitude/longitude readings ✴and lots more... vides valuable events as the first flush of overland run- from a Geographic Positioning System wildlife habitat off transports nonpoint-source (nutri- (GPS). We also calculated the edge- while enhancing ent) pollution into the stream corridors to-area ratio for each riparian zone to instream habitat (Burke and Grime 1996). -

Arboreal Arthropod Predation on Early Instar Douglas-Fir Tussock Moth Redacted for Privacy

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Becky L. Fichter for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomologypresented onApril 23, 1984. Title: Arboreal Arthropod Predation on Early Instar Douglas-fir Tussock Moth Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: William P. StOphen Loss of early instar Douglas-fir tussock moth( Orgyia pseudotsugata McDunnough) (DFTM) has been found to constitute 66-92% of intra-generation mortality and to be a key factor in inter-generation population change. This death has been attributed to dispersal and to arthropod predation, two factors previously judged more important to an endemic than an outbreak population. Polyphagous arthropod predators are abundant in the forest canopy but their predaceous habits are difficult to document or quantify. The purpose of the study was to develop and test a serological assay, ELISA or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, for use as an indirect test of predation. Development of this assay involved production of an antiserum reactive with DFTM but not reactive with material from any coexisting lepidopteran larvae. Two-dimensional immunoelectrophoresis was used to select a minimally cross-reactive fraction of DFTM hemolymph as the antigen source so that a positive response from a field-collected predator would correlate unambiguously with predation on DFTM. Feeding trials using Podisus maculiventris Say (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae) and representative arboreal spiders established the rate of degredation of DFTM antigens ingested by these predators. An arbitrary threshold for deciding which specimens would be considered positive was established as the 95% confidence interval above the mean of controls. Half of the Podisus retained 0 reactivity for 3 days at a constant 24 C. -

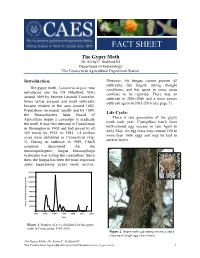

The Gypsy Moth Dr

FACT SHEET The Gypsy Moth Dr. Kirby C. Stafford III Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Introduction: However, the fungus cannot prevent all outbreaks, due largely during drought The gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, was conditions, and hot spots in some areas introduced into the US (Medford, MA) continue to be reported. There was an around 1869 by Etienne Leopold Trouvelot. outbreak in 2005-2006 and a more severe Some larvae escaped and small outbreaks outbreak again in 2015-2016 (see page 7). became evident in the area around 1882. Populations increased rapidly and by 1889, the Massachusetts State Board of Life Cycle: Agriculture began a campaign to eradicate There is one generation of the gypsy the moth. It was first detected in Connecticut moth each year. Caterpillars hatch from in Stonington in 1905 and had spread to all buff-colored egg masses in late April to 169 towns by 1952. In 1981, 1.5 million early May. An egg mass may contain 100 to acres were defoliated in Connecticut (Fig. more than 1000 eggs and may be laid in 1). During an outbreak in 1989, CAES several layers. scientists discovered that the entomopathogenic fungus Entomophaga maimaiga was killing the caterpillars. Since then, the fungus has been the most important agent suppressing gypsy moth activity. 1600000 1400000 1200000 1000000 800000 600000 400000 Acres defoliation bygypsy moth defoliation Acres 200000 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Year Figure 1. Number of acres defoliated by the gypsy moth in Connecticut, 1969-2016. Figure 2. Gypsy moth egg masses on a tree and a close-up of single egg mass (inset).