The Philosophy of Error and Liberty of Thought JS Mill on Logical Fallacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Correspondence of Peter Macowan (1830 - 1909) and George William Clinton (1807 - 1885)

The Correspondence of Peter MacOwan (1830 - 1909) and George William Clinton (1807 - 1885) Res Botanica Missouri Botanical Garden December 13, 2015 Edited by P. M. Eckel, P.O. Box 299, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri, 63166-0299; email: mailto:[email protected] Portrait of Peter MacOwan from the Clinton Correspondence, Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo, New York, USA. Another portrait is noted by Sayre (1975), published by Marloth (1913). The proper citation of this electronic publication is: "Eckel, P. M., ed. 2015. Correspondence of Peter MacOwan(1830–1909) and G. W. Clinton (1807–1885). 60 pp. Res Botanica, Missouri Botanical Garden Web site.” 2 Acknowledgements I thank the following sequence of research librarians of the Buffalo Museum of Science during the decade the correspondence was transcribed: Lisa Seivert, who, with her volunteers, constructed the excellent original digital index and catalogue to these letters, her successors Rachael Brew, David Hemmingway, and Kathy Leacock. I thank John Grehan, Director of Science and Collections, Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo, New York, for his generous assistance in permitting me continued access to the Museum's collections. Angela Todd and Robert Kiger of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie-Melon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, provided the illustration of George Clinton that matches a transcribed letter by Michael Shuck Bebb, used with permission. Terry Hedderson, Keeper, Bolus Herbarium, Capetown, South Africa, provided valuable references to the botany of South Africa and provided an inspirational base for the production of these letters when he visited St. Louis a few years ago. Richard Zander has provided invaluable technical assistance with computer issues, especially presentation on the Web site, manuscript review, data search, and moral support. -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

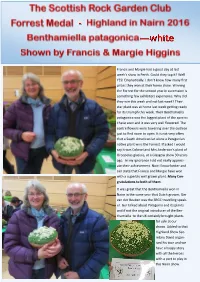

Francis and Margie Had a Good Day at Last Week's Show in Perth. Could They Top It? Well YES! Emphatically. I Don't Know

Francis and Margie had a good day at last week’s show in Perth. Could they top it? Well YES! Emphatically. I don’t know how many first prizes they won at their home show. Winning the Forrest for the second year in succession is something few exhibitors experience. Why did they win this week and not last week? Their star plant was at home last week getting ready for its triumph this week. Their Benthamiella patagonica was the biggest plant of the species I have seen and it was very well flowered. The centre flowers were towering over the cushion just to find room to open. It is not very often that a South American let alone a Patagonian native plant wins the Forrest. If asked I would say it was Colonel and Mrs Anderson’s plant of Oreopolus glaciais, at a Glasgow show 30 years ago. In my ignorance I did not really appreci- ate their achievement. Now I know better and can state that Francis and Margie have won with a superbly well grown plant. Many Con- gratulations to both of them. It was great that the Benthamiella won in Nairn in the same year that Dutch grower, Ger van der Beuken was the SRGC travelling speak- er. Ger talked about Patagonia and its plants and if not the original introducer of the Ben- thamiella to the UK certainly brought plants for sale at our shows. Added to that Highland Show Sec- retary David organ- ised his tour and we have a happy story with all the heroes with a part to play in this Nairn show. -

Asa Gray's Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830S-1860S)

Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray's Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Hung, Kuang-Chi. 2013. Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray's Citation Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 4:20:57 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11181178 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray’s Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) A dissertation presented by Kuang-Chi Hung to The Department of the History of Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts July 2013 © 2013–Kuang-Chi Hung All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Janet E. Browne Kuang-Chi Hung Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray’s Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) Abstract It is well known that American botanist Asa Gray’s 1859 paper on the floristic similarities between Japan and the United States was among the earliest applications of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory in plant geography. Commonly known as Gray’s “disjunction thesis,” Gray's diagnosis of that previously inexplicable pattern not only provoked his famous debate with Louis Agassiz but also secured his role as the foremost advocate of Darwin and Darwinism in the United States. -

Reader 19 05 19 V75 Timeline Pagination

Plant Trivia TimeLine A Chronology of Plants and People The TimeLine presents world history from a botanical viewpoint. It includes brief stories of plant discovery and use that describe the roles of plants and plant science in human civilization. The Time- Line also provides you as an individual the opportunity to reflect on how the history of human interaction with the plant world has shaped and impacted your own life and heritage. Information included comes from secondary sources and compila- tions, which are cited. The author continues to chart events for the TimeLine and appreciates your critique of the many entries as well as suggestions for additions and improvements to the topics cov- ered. Send comments to planted[at]huntington.org 345 Million. This time marks the beginning of the Mississippian period. Together with the Pennsylvanian which followed (through to 225 million years BP), the two periods consti- BP tute the age of coal - often called the Carboniferous. 136 Million. With deposits from the Cretaceous period we see the first evidence of flower- 5-15 Billion+ 6 December. Carbon (the basis of organic life), oxygen, and other elements ing plants. (Bold, Alexopoulos, & Delevoryas, 1980) were created from hydrogen and helium in the fury of burning supernovae. Having arisen when the stars were formed, the elements of which life is built, and thus we ourselves, 49 Million. The Azolla Event (AE). Hypothetically, Earth experienced a melting of Arctic might be thought of as stardust. (Dauber & Muller, 1996) ice and consequent formation of a layered freshwater ocean which supported massive prolif- eration of the fern Azolla. -

Bentham and Hooker Classification Faculty Name - Dr Piyush Kumar Rai Email – [email protected]

Course - B.Sc. Botany Semester - II Paper Code - BOT GE202 Paper Name – Plant Ecology and Taxonomy Topic - Bentham and Hooker Classification Faculty Name - Dr Piyush Kumar Rai Email – [email protected] Bentham and Hooker Classification George Bentham (1800 – 1884) Joseph Hooker (1817 – 1911) It was Proposed by George Bentham ( 1800 – 1884 ) and Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817 – 1911 ) in their Genera Plantarum published during July (1862 ) & April ( 1883 ) George Bentham (1800 – 1884) and Joseph Dalton Hooker ( 1817 ) – 1911) , the two British botanist who were associated with the Royal Botanic garden at kew ( England) gave most important and easily workable system of classification of angiosperms and published it in three volume of ‘Genera plantarum ‘ The first part of Genera plantarum appeared in July 1882 and the last part in April 1883 . This was the greatest taxonomic work ever produced in the united kingdom and ever since been an inspiration to generations of kew botanists . Although Bentham and Hooker’s system of classification was based on that of A.P. de Candolle but greater stress was given on contrast between free and fused petals . Their symptom was widely accepted in Britain and commonwealth countries but in Europe and North America it did not hold the much ground . Bentham and Hooker divided the seed plants into Dicotyledons, Gymnosperms and Monocotyledons. They placed Ranales in beginning and grasses at the end . The following is the summary of Bentham & Hooker’s system. DICOTYLEDONS : A . Polypetalae ( petals are free ) Series l Thalamiflorae Order 1. Ranales eg. Ranunculaceae, Magnollaceae e.t.c Order 2. Parietales eg. Papaveraceae , Cruciferae e.t.c Order 3. -

Sir Joseph Hooker's Collections at the Royal

Fig. 1. Portrait of Sir Joseph Hooker in his study, pencil drawing by Theodore Blake Wirgman, 1886 (Kew Art Collection). SIR JOSEPH HOOKER’S COLLECTIONS AT THE ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS, KEW David Goyder, Pat Griggs, Mark Nesbitt, Lynn Parker and Kiri Ross-Jones Introduction On the December 9, 2011, just one day short of the centenary of the death of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, his life and work were celebrated by over 150 participants at a conference at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The afternoon session consisted of displays of Sir Joseph’s collections in the Herbarium building, ranging from herbarium specimens and economic botany to art, archives and books. This paper attempts to capture the experience in a more permanent form, highlighting the quantity and quality of collections accumulated during Sir Joseph’s career, both in his official role as Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 2012 vol. 29 (1): pp. 66–85 66 © The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2012. Director of Kew, and as an avid collector and scientist from childhood to his death. We aim to demonstrate that these collections are larger and more intact than is usually appreciated, and that they form a rich resource for scientific and historical research. Current work at Kew on cataloguing and digitisation is making many of these collections increasingly accessible. Any one strand of work in Joseph Hooker’s long life, from 1817 to 1911, would have been a remarkable achievement (Endersby, 2004; Griggs, 2011). His travels and collecting in Antarctica and the South Pacific, Sikkim and Nepal, the Near East, Morocco and the western United States led to the discovery of many new species, and important introductions of garden plants to Europe (Desmond, 1999). -

BOTANICAL INVESTIGATION of Appendices Bibliography

BOTANICAL INVESTIGATION OF NEW SOUTH WALES 1811-1880 Volume III Appendices Bibliography L.A. Gilbert, September, 1971. APPENDICES I N.S.W. Collectors acknowledged by George Bentham in Flora Australiensis 1 II Allan Cunninghams Letter to Sir Joseph Banks, 1 December 1817 12 III Manna 15 IV Plants collected during Mitchell's First Three Expeditions, 1831-1836, and described by Dr John Lindley as new species, 1838 25 V Plants collected during Sturts Expedition into the Interior, 1844-1846, and described by Robert Brown, 1849 30 VI Plants described as new from the Collection made by Sir Thomas Mitchell during his Tropical Australia Expedition, 1845-1846 33 VII William Stephenson, M.R.C.S., Surgeon and Naturalist 41 VIII A Sample of Nineteenth Century Uses for Certain N.S.W. Plants indicating the diverse ways in which the settlers used the bush to supply some basic needs 46 IX Further Examples of Bush Buildings 179 X Notes on Captain Daniel Woodriffs "Extracts from Mr Moores Report to Gov. Macquarie on Timber fit for Naval Purposes" 187 XI Lieut. James Tuckey's Report on N.S.W. Timber, 1802-1804 190 XII "List of Prevailing Timber Trees of New South Wales", c.1820. J.T. Bigge: Report (Appendix) 195 XIII Expansion of Settlement in N.S.W. due to the occurrence of Red Cedar 199 XIV Visits by Non-British Scientific and Survey Expeditions to N.S.W., 1788-1858 . 202 XV Botanical Names and Authors of Plants mentioned in this Study 207 APPENDIX I. N.S.I. COLLECTORS ACKNOWLEDGED BY GEORGE BENTHAM IN FLORA AUSTRALIENSIS "Wc find the botanical work of one State sufficiently engrossing, and thus in botanical matters we are rev- ersing the act of federation, which politically unites all our peoples. -

Bentham and Hooker's Classification (1862 – ’83)

Bentham and Hooker's classification (1862 – ’83) George Bentham and Joseph Dalton Hooker - Two English taxonomists who were closely associated with the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew, England have given a detailed classification of plant kingdom, particularly the angiosperms. They gave an outstanding system of classification of phanerogams in their Genera Plantarum which was published in three volumes between the years 1862 to 1883. It is a natural system of classification. However, it does not show the evolutionary relationship between different groups of plants, in the strict sense. Nevertheless, it is the most popular system of classification particularly for angiosperms. The popularity comes from the face that very clear key characters have been listed for each of the families. These key characters enable the students of taxonomy to easily identify and assign any angiosperm plant to its family. Bentham and Hooker have grouped advanced, seed bearing plants into a major division called Phanerogamia. This division has been divided into three classes namely: 1. Dicotyledonae 2. Gymnospermae and 3. Monocotyledoneae 84 45 36 3 34 PhanerogamsSummaryor spermatophyta of Benthamare anddivided Hooker'sinto three classificationclasses - Dicotyledonae (1862 – 83), Gymnospermae and Monocotyledonae Class - Dicotyledonae– two cotyledons, open vascular bundles, reticulate venation I. Sub-Class Polypetalae - The flowers are usually with two distinct whorls of perianth; the segments of the inner whorl or "corolla" are free. A. Series-Thalamiflorae -(The calyx consists of usually distinct sepals, which are free from the ovary; doom shaped thalamus). 6 Orders/Cohort; 34 Families or Natural orders -R B. Series – Disciflorae - The calyx consists of either distinct or united sepals, which may be free or adnate to the ovary; a prominent ring of cushion shaped disc is usually present below the ovary, sometimes broken up into glands; the stamens are usually definite in number, inserted upon, or at the outer or inner base of the disc; the ovary is superior. -

ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS, KEW Records and Collections, 1768-1954 Reels M730-88

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS, KEW Records and collections, 1768-1954 Reels M730-88 Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond London TW9 3AE National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1970-71 CONTENTS Page 4 Historical note 7 Kew collectors series, 1814-55 9 Papers relating to collectors, 1791-1865 10 Official correspondence of Sir William Hooker, 1825-65 17 Official correspondence, 1865-1928 30 Miscellaneous manuscripts 30 Manuscript of James Backhouse 30 Letters to John G. Baker, 1883-90 31 Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, 1768-1819 33 Papers of George Bentham, 1834-1882 35 Papers of Henry Burkill, 1893-1937 35 Records of HMS Challenger, 1874-76 36 Manuscript of Frederick Christian 36 Papers of Charles Baron Clarke 36 Papers of William Colenso, 1841-52 37 Manuscript of Harold Comber, 1929-30 37 Manuscripts of Allan Cunningham, 1826-35 38 Letter of Charles Darwin, 1835 38 Letters to John Duthie, 1878-1905 38 Manuscripts of A.D.E. Elmer, 1907-17 39 Fern lists, 1846-1904 41 Papers of Henry Forbes, 1881-86 41 Correspondence of William Forsyth, 1790 42 Notebook of Henry Guppy, 1885 42 Manuscript of Clara Hemsley, 1898 42 Letters to William Hemsley, 1881-1916 43 Correspondence of John Henslow, 1838-39 43 Diaries of Sir Arthur Hill, 1927-28 43 Papers of Sir Joseph Hooker, 1840-1914 2 48 Manuscript of Janet Hutton 49 Inwards and outwards books, 1793-1895 58 Letters of William Kerr, 1809 59 Correspondence of Aylmer Bourke Lambert, 1821-40 59 Notebooks of L.V. -

John Torrey: a Botanical Biography

Reveal, J.L. 2014. John Torrey: A botanical biography. Phytoneuron 2014-100: 1–64. Published 14 October 2014. ISSN 2153 733X JOHN TORREY: A BOTANICAL BIOGRAPHY JAMES L. REVEAL School of Integrative Plant Science Plant Biology, 412 Mann Building Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853-4301 [email protected] ABSTRACT The role played by the American botanist John Torrey (1796–1873) in the development of floristics and the naming of plants, especially from the American West, is shown to be fundamental not only for present-day taxonomists in their monographic and floristics studies, and to historians in understanding the significance of discovering new and curious objects of nature in the exploration of the West but also the role Torrey directly and indirectly played in the development of such institutions as the New York Botanical Garden and the Smithsonian Institution. For the author of this 2014 paper, the name of John Torrey dates back to his earliest years of interests in botany, some 56 years ago, as even then Torrey was the kind of hero he could admire without resorting to comic books or movies. John Torrey has long been a “founding father” of North American systematic botany. Even so it was probably a bit unusual that a high school kid from the Sierra Nevada of California should know the name and even something about the man. It was Torrey who described plants with the explorer John Charles Frémont 1, and so by fate the three of us were thrown together while I penned a paper for a history class at Sonora Union High School in the spring of 1958.