Dyslexia and Hyperlexia in Bilinguals à R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the Key Concept to Its Definition by Writing the Letter in the Correct Blank

AP HANDOUT 2A Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the key concept to its definition by writing the letter in the correct blank. Set A 1. ______ decoding A. Understanding that the sequence of letters in written words represents the sequence of sounds (or phonemes) in spoken words 2. ______common sound B. Sound that a letter most frequently makes in a word 3. ______decodable texts C. Vowels and certain consonant sounds that can be prolonged during pronunciation and are easier to say without being distorted 4. ______ encoding D. Engaging and coherent texts in which most of the words are comprised of an accumulating sequence of letter-sound correspondences being taught 5. ______ alphabetic E. Process of converting printed words into their spoken principle forms by using knowledge of letter-sound relationships and word structure 6. ______ continuous F. Process of converting spoken words into their written sounds forms (spelling) SET B 7. ______ sounding out G. Words in which some or all of the letters do not represent their most common sounds 8. ______ letter H. Groups of consecutive letters that represent a particular recognition sound(s) in words 9. ______ irregular words I. Ability to distinguish and name each letter of the alphabet, sequence the letters, and distinguish and produce both upper and lowercase letters 10. ______ regular words J. Relationships between common sounds of letters or letter combinations in written words 11. ______ stop sounds K. Words in which the letters make their most common sound 12. ______ letter-sound L. Process of saying each sound that represents a letter(s) in correspondences a word and blending them together to read it 13. -

The End of Illiteracy?

The End of Illiteracy? The Holy Grail of Clackmannanshire TOM BURKARD CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 1999 THE AUTHOR Tom Burkard is the Secretary of the Promethean Trust and has published several articles on how children learn to read. He contributed to the 1997 Daily Telegraph Schools Guide, and is a member of the NASUWT. His main academic interest is the interface between reading theory and classroom practice. His own remedial programme, recently featured in the Dyslexia Review, achieved outstanding results at Costessey High School in Norwich. His last Centre for Policy Study pamphlet, Reading Fever: Why phonics must come first (written with Martin Turner in 1996) proved instrumental in determining important issues in the National Curriculum for teacher training colleges. Acknowledgements Support towards research for this Study was given by the Institute for Policy Research. The Centre for Policy Studies never expresses a corporate view in any of its publications. Contributions are chosen for their independence of thought and cogency of argument. ISBN No. 1 897969 87 2 Centre for Policy Studies, March 1999 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 - 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. A brief history of the ‘reading wars’ 4 3. A comparison of analytic and synthetic phonics 9 4. Problems with the National Literacy Strategy 12 5. The success of synthetic phonics 17 6. Introducing synthetic phonics into the classroom 20 7. Recommendations 22 Appendix A: Problems with SATs 25 Appendix B: A summary of recent research on analytic phonics 27 Appendix C: Research on the effectiveness of synthetic phonics 32 SUMMARY The Government’s recognition of the gravity of the problem of illiteracy in Britain is welcome. -

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

Alphabetic Principle

Alphabetic Principle What is it? The alphabetic principle refers to the understanding that there are predictable and consistent relations between written letters and spoken sounds – the combination of letter knowledge and awareness. The 26 letters are the “key” to the English language. They have names, shapes, sounds, and go together to make words. Why is it important? Children's knowledge of letter names, shapes and sounds is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters. As this becomes internalized we will see writing and reading skills grow. Considerations: (what to think about?) • Be intentional with the purpose and clear with the expectations. “We are going to be learning about the letters of the alphabet. There are 26 letters (use the abc line to count together slowly while you touch them). You all have some of them in your names (check that out with their name cards). Letters have sounds and go together to make words. Your name is a word….” How cool is that!!” Make it interesting and meaningful. Revisit the learning often … “What letters do you know really well? Which ones are still tricky?” Kids can answer this! • Have 2 alphabet strips - one high to teach from and one low for students to access (have a special abc pointer to reach the high one when you teach from it). Have them run in one long line. • Be very explicit when talking about the alphabet and clear when enunciating. -

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research The alphabetic principle is composed of two parts: • Alphabetic Understanding: Words are composed of letters that represent sounds. • Phonological Recoding: Using systematic relationships between letters and phonemes (letter-sound correspondence) to retrieve the pronunciation of an unknown printed string or to spell words. Phonological recoding consists of: o Regular Word Reading o Irregular Word Reading o Advanced Word Analysis Regular Word Reading A regular word is a word in which all the letters represent their most common sounds. Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded). Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1997). Beginning decoding ("phonological recoding") is the ability to: • read from left to right, simple, unfamiliar regular words. • generate the sounds for all letters. • blend sounds into recognizable words. Beginning spelling is the ability to: • translate speech to print using phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter-sounds. Progression of Regular Word Reading Skills Sight Word Sounding Saying the Reading Automatic Out Whole Word (sounding out Word (saying (saying each the word in your Reading each individual sound head, if (reading the individual and pronouncing necessary, and word without sound out the whole word) saying the sounding it -

Building the Alphabetic Principle in Young Children Who Are Deaf Or Hard of Hearing

The Volta Review, Volume 109(2-3), Fall/Winter 2009, 87–119 Building the Alphabetic Principle in Young Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing Jessica Page Bergeron , M.E.D. ; Amy R. Lederberg, Ph.D. ; Susan R. Easterbrooks, Ed.D. ; Elizabeth Malone Miller, M.S. ; and Carol McDonald Connor, Ph.D. Acquisition of phoneme-grapheme correspondences, a key concept of the alphabetic principle, was examined in young children who are deaf or hard of hearing (DHH) using a semantic association strategy embedded in two interventions, the Children’s Early Intervention and Foundations for Literacy. Single-subject design experiments using multiple baselines across content were used to examine the functional relation- ship between student outcomes and the intervention provided. Only students who were able to identify spoken words were included in the studies. Study One was con- ducted with 5 children 3.10–7.10 years of age in oral or signing programs. Study Two was conducted with 5 children 3.10–4.5 years of age in an oral program. All children acquired taught phoneme-grapheme correspondences. These findings provide much- needed evidence that children who are DHH and who have some speech perception abilities can learn critical phoneme-grapheme correspondences through explicit audi- tory skill instruction with language and visual support. Jessica Page Bergeron, M.E.D., is a Cognitive Developmental Specialist in the Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education at Georgia State University; Amy R. Lederberg, Ph.D., is a Professor in the Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education at Georgia State University; Susan R. -

1 the Whole Language Approach to Reading

1 The Whole Language Approach to Reading: An empiricist critique A revised version of: Hempenstall, K. (1996). The whole language approach to reading: An empiricist critique. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 1(3), 22-32. Historically, the consideration of learning disability has emphasised within-person factors to explain the unexpected difficulty that academic skill development poses for students with such disability. Unfortunately, the impact of the quality of initial and subsequent instruction in ameliorating or exacerbating the outcomes of such disability has received rather less exposure until recently. During the 1980’s an approach to education, whole language, became the major model for educational practice in Australia (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Employment, Education, and Training, 1992). Increasing controversy developed, both in the research community (Eldredge, 1991; Fields & Kempe, 1992; Gersten & Dimino, 1993; Liberman & Liberman, 1990; Mather, 1992; McCaslin, 1989; Stahl & Miller, 1989; Vellutino, 1991; Weir, 1990), and in the popular press (Hempenstall, 1994, 1995; Prior, 1993) about the impact of the approach on the attainments of students educated within this framework. In particular, concern was expressed (Bateman, 1991; Blachman, 1991; Liberman, Shankweiler, & Liberman, 1989; Yates, 1988) about the possibly detrimental effects on "at-risk" students (including those with learning disabilities). Whole language: History The whole language approach has its roots in the meaning-emphasis, whole-word model of teaching reading. Its more recent relation was an approach called "language experience" which became popular in the mid-1960's. The language experience approach emphasized the knowledge which children bring to the reading situation - a position diametrically opposed to the Lockian view of "tabula rasa" (the child's mind as a blank slate on which education writes its message). -

What Should Every ESL Teacher Know? What Should Every ESL Teacher Comparing the Features of ESL and EFL Teaching ESL and of Features the Comparing

Table of Contents Introduction ··································································································································· 6 Chapter 1 How Does ESL Diff er from EFL? ······································································ 7 - What Are the Important Features of ESL? ············································································· 8 Chapter 2 Needs Analysis and Environment Analysis and One-to-One Tutoring with Adult ESL Learners ································································· 12 - Needs Analysis ······························································································································· 13 - Environment Analysis ·················································································································· 13 - Needs and Environment Analysis in One-to-One Tutoring ············································ 15 - What Should You Learn from This Chapter? ········································································· 21 Chapter 3 Needs and Environment Analysis When Teaching Small Classes for Adults ···················································································································· 23 - Needs Analysis for Small Classes ····························································································· 23 - Environment Analysis for Small Classes ················································································ 29 - What Should You Learn -

Traditional Phonics, Whole Language, and Spelling Before

A comparison of three approaches to literacy acquisition : traditional phonics, whole language, and spelling before reading by Roxanne L Sporleder A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Montana State University © Copyright by Roxanne L Sporleder (1998) Abstract: A quasi-experimental research design was used to compare three approaches to literacy acquisition in nine first-grade classrooms to determine if there was a significant difference in achievement in phoneme segmentation, reading, and spelling development at the end of twenty-one weeks of instruction. All nine classrooms within one school district with a total of 151 first-grade students received instruction in reading following the district curriculum guidelines and using a newly adopted literature-based reading series. The basal provided a wide variety of opportunities to read, write, and talk about meaning. In addition to the basic reading program, students in the nine classrooms received differentiating instruction. Three classrooms were introduced to phonics within the context of literature and learned spelling using word families. Three classrooms received direct instruction in phonics using a traditional approach to learning letter sounds, blending words, and reading short controlled texts. These also learned spelling using word families. Another three classrooms received instruction in the letter representations of phonemes with an emphasis on metacognition and spelling words before ever reading them. At the beginning of the school year, students were given baseline tests to identify phoneme segmentation skills, letter knowledge, spelling development and reading ability. At the end of twenty-one weeks, these same tests as well as the WRMT-R were administered. -

Evidence-Based Strategies for Improving Early Literacy Part #2

2/25/2020 Welcome to Evidence-Based Strategies for Improving Early Literacy Part #2: Developing Automaticity with Early Phonics Skills 1 My world… 2 My world… 3 1 2/25/2020 Webinar #1: Phonological Awareness Developing Phonological Awareness provides the foundation for students’ reading success in the future. Refine your ability to deliver high quality phonological awareness for both core instruction as well as intervention. Webinar #2: Developing Automaticity with Early Phonics Skills Areas of focus Refine your ability to deliver efficient, high-quality phonics instruction using evidence-based routines. We will investigate the routines and watch examples of effective phonics for each instruction in rural Alaskan classrooms. webinar in Webinar #3: Developing Automaticity with Advanced Phonics Explore how to deliver efficient, high-quality instruction with this series… complex vowel patterns, affixes, and multisyllabic words. Our discussion will be enhanced by examining video of teachers using evidence-based routines in rural Alaskan classrooms. Webinar #4: Developing Accurate and Fluent Readers in Connected Text Strengthen your skills in using decodable text and dictation to support accuracy and fluency in connected text. 4 Learning Intention for today: Learn to provide Phonics instruction so that all students are able to accurately associate spelling patterns with sounds and decode complex spelling patterns in words. Success Criteria: 1. I can identify the Phonics Skills in the Alaska ELA Standards. 2. I can deliver phonics instruction with accuracy and efficiency. 5 Reading Requires… Decoding X Comprehension Phonics Vocabulary PA Fluency Text Comprehension 6 2 2/25/2020 Timeline of Essential Elements of Reading Grade K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Phonemic Awareness Advanced Word Study Phonics (Alphabetic Principle) Accuracy and Fluency with Connected Text Vocabulary Comprehension 7 Recommendations Recommendation 1 - Teach students academic language skills, including the use of inferential and narrative language, and vocabulary knowledge. -

Free Full Text

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 79 (2017) 134–149 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neubiorev Review article Hyperlexia: Systematic review, neurocognitive modelling, and outcome MARK Alexia Ostrolenka,b,c, Baudouin Forgeot d’Arca,b,c, Patricia Jelenica,b, Fabienne Samsona,b, ⁎ Laurent Mottrona,b,c, a Centre d’excellence en Troubles Envahissants du Développement de l’Université de Montréal (CETEDUM), Hôpital Rivière-des-Prairies, 7070 Boulevard Perras, H1E 1A4, Montréal, QC, Canada b Centre de recherche du CIUSSS du Nord de l’Île de Montréal, Québec, Canada c Département de Psychiatrie, Université de Montréal, H3T 1J4, Québec, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Hyperlexia is defined as the co-occurrence of advanced reading skills relative to comprehension skills or general Hyperlexia intelligence, the early acquisition of reading skills without explicit teaching, and a strong orientation toward Autism written material, generally in the context of a neurodevelopmental disorder. In this systematic review of cases Reading (N = 82) and group studies (including 912 participants of which 315 are hyperlexic), we address: whether the Decoding hyperlexic profile is associated with autism and why, whether models of non-autistic reading can teach us about Review hyperlexia, and what additional information we can get from models specific to autistic cognitive functioning. Enhanced perceptual functioning model fi fi Visual word form area We nd that hyperlexia, or a hyperlexic-like pro le, characterises a substantial portion of the autistic spectrum, in which the subcomponents of the typical reading architecture are altered and dissociated. Autistic children follow a chronologically inverted path when learning to read, and make extended use of the perceptual expertise system, specifically the visual word form recognition systems. -

And Sight-Word Instruction

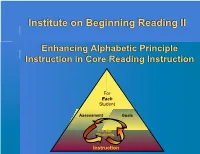

For Each Student Assessment Goals For All Students Instruction . Oregon Department of Education . Institute for the Development of Educational Achievement, College of Education, University of Oregon . U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs Harn, Simmons, & Kame'enui © 2003 2 Content developed by: Edward J. Kame’enui, Ph. D. Deborah C. Simmons, Ph. D. Professor, College of Education Professor, College of Education University of Oregon University of Oregon Beth Harn, Ph.D. Michael D. Coyne, Ph. D. University of Oregon University of Connecticut David Chard, Ph. D. University of Oregon Additional support: Patrick Kennedy-Paine Katie Tate Nicole Sherman-Brewer University of Oregon Oregon Reading First Harn, Simmons, & Kame'enui © 2003 3 . All materials are copy written and should not be reproduced or used without expressed permission of Dr. Edward J. Kame’enui or Dr. Deborah C. Simmons. Selected slides were reproduced from other sources and original references cited. Harn, Simmons, & Kame'enui © 2003 4 Schoolwide: Each & All Prevention Oriented Scientifically Based Harn, Simmons, & Kame'enui © 2003 5 1. Goals: What outcomes do we want for our students in our state, district, and schools? 2. Knowledge: What do we know and what guidance can we gain from scientifically based reading research? 3. Progress Monitoring Assessment: How are we doing? What is our current level of performance as a school? As a grade? As a class? As an individual student? Today’s Focus 4. Outcome Assessment: How far do we need to go to reach our goals and outcomes? 5. Core Instruction: What are the critical components that need to be in place to reach our goals? 6.