PCI Reading Program Research and References Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the Key Concept to Its Definition by Writing the Letter in the Correct Blank

AP HANDOUT 2A Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the key concept to its definition by writing the letter in the correct blank. Set A 1. ______ decoding A. Understanding that the sequence of letters in written words represents the sequence of sounds (or phonemes) in spoken words 2. ______common sound B. Sound that a letter most frequently makes in a word 3. ______decodable texts C. Vowels and certain consonant sounds that can be prolonged during pronunciation and are easier to say without being distorted 4. ______ encoding D. Engaging and coherent texts in which most of the words are comprised of an accumulating sequence of letter-sound correspondences being taught 5. ______ alphabetic E. Process of converting printed words into their spoken principle forms by using knowledge of letter-sound relationships and word structure 6. ______ continuous F. Process of converting spoken words into their written sounds forms (spelling) SET B 7. ______ sounding out G. Words in which some or all of the letters do not represent their most common sounds 8. ______ letter H. Groups of consecutive letters that represent a particular recognition sound(s) in words 9. ______ irregular words I. Ability to distinguish and name each letter of the alphabet, sequence the letters, and distinguish and produce both upper and lowercase letters 10. ______ regular words J. Relationships between common sounds of letters or letter combinations in written words 11. ______ stop sounds K. Words in which the letters make their most common sound 12. ______ letter-sound L. Process of saying each sound that represents a letter(s) in correspondences a word and blending them together to read it 13. -

Fry 1000 Instant Words: Free Flash Cards and Word Lists for Teachers

Fry 1000 Instant Words: Free Flash Cards and Word Lists For Teachers Fry 1000 Instant Words Bulletin Board Display Banner and 26 Letter Cards The Fry 1000 Instant Words are a list of the most common words used for teaching reading, writing, and spelling. These high frequency words should be recognized instantly by readers. Dr. Edward B. Fry's Instant Words (which are often referred to as the "Fry Words") are the most common words used in English ranked in order of frequency. In 1996, Dr. Fry expanded on Dolch's sight word lists and research and published a book titled "Fry 1000 Instant Words." In his research, Dr. Fry found the following results: 25 words make up approximately 1/3 of all items published. 100 words comprise approximately 1/2 of all of the words found in publications. 300 words make up approximately 65% of all written material. Over half of every newspaper article, textbook, children's story, and novel is composed of these 300 words. It is difficult to write a sentence without using several of the first 300 words in the Fry 1000 Instant Words List. Consequently, students need to be able to read the first 300 Instant Words without a moment's hesitation. Do not bother copying these 3 lists. You will be able to download free copies of these lists, plus 7 additional lists that are not shown (words 301 - 1000), using the free download links that are found later on this page. In addition to these 10 free lists of Fry's sight words, I have created 1000 color coded flashcards for all of the Fry 1000 Instant Words. -

Sight Word Poems Easy-To-Read Reproducible Poems That Target & Teach 100 Words from the Dolch List by Rosalie Franzese

10 0 Super Sight Word Poems Easy-to-Read Reproducible Poems That Target & Teach 100 Words From the Dolch List by Rosalie Franzese Edited by Eileen Judge Cover design by Maria Lilja Interior design by Brian LaRossa ISBN: 978-0-545-23830-4 Copyright © 2012 by Rosalie Franzese All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc. Printed in the U.S.A. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 40 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 100 Super Sight Word Poems © Rosalie Franzese, Scholastic Teaching Resources Introduction .................... 4 Our Class (we) ................. 32 Teaching Strategies .............. 5 Where Is My Teacher? (she) ...... 33 Activities ....................... 8 Love, Love, Love (me) ........... 34 Meeting the Common Core What Can I Be? (be) ............ 35 State Standards .................11 Look in the Sky (look). 36 References .....................11 The Library (at) ................ 37 Dolch Word List ................ 12 Look at That! (that) ............. 38 I Ran (ran) .................... 39 POEMS In the Fall (all) ................. 40 A Park (a) ..................... 13 You and Me (you) .............. 41 Me (I) ........................ 14 Do You? (do) .................. 42 The School (the) ............... 15 Setting the Table (here) ......... 43 I Go (go) ...................... 16 You Are My Puppy (are) ......... 44 Where To? (to) ................. 17 In My Room (there) ............. 45 I See the Animals (see) .......... 18 Where, Oh, Where? (where) ...... 46 My Room (my) ................. 19 Going, Going, Going (going) ...... 47 Feelings (am) .................. 20 What Is It For? (for) .............48 I Go In (in) .................... 21 What Is It Good For? (good) ...... 49 Here I Go! (on). 22 Come With Me (come) .......... 50 My Family (is) .................. 23 My Halloween Party (came) ...... 51 What Is It? (it) ................. -

The End of Illiteracy?

The End of Illiteracy? The Holy Grail of Clackmannanshire TOM BURKARD CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 1999 THE AUTHOR Tom Burkard is the Secretary of the Promethean Trust and has published several articles on how children learn to read. He contributed to the 1997 Daily Telegraph Schools Guide, and is a member of the NASUWT. His main academic interest is the interface between reading theory and classroom practice. His own remedial programme, recently featured in the Dyslexia Review, achieved outstanding results at Costessey High School in Norwich. His last Centre for Policy Study pamphlet, Reading Fever: Why phonics must come first (written with Martin Turner in 1996) proved instrumental in determining important issues in the National Curriculum for teacher training colleges. Acknowledgements Support towards research for this Study was given by the Institute for Policy Research. The Centre for Policy Studies never expresses a corporate view in any of its publications. Contributions are chosen for their independence of thought and cogency of argument. ISBN No. 1 897969 87 2 Centre for Policy Studies, March 1999 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 - 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. A brief history of the ‘reading wars’ 4 3. A comparison of analytic and synthetic phonics 9 4. Problems with the National Literacy Strategy 12 5. The success of synthetic phonics 17 6. Introducing synthetic phonics into the classroom 20 7. Recommendations 22 Appendix A: Problems with SATs 25 Appendix B: A summary of recent research on analytic phonics 27 Appendix C: Research on the effectiveness of synthetic phonics 32 SUMMARY The Government’s recognition of the gravity of the problem of illiteracy in Britain is welcome. -

The Effect of Sight Word Instruction on the Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students Mary Riscigno Submitted in Partial Fulf

The Effect of Sight Word Instruction on the Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students Mary Riscigno Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education May 2019 Graduate Programs in Education Goucher College Table of Contents List of Tables i Abstract ii I. Introduction 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Statement of Research Hypothesis 2 Operational Definitions 2 II. Review of the Literature 3 Early Literacy Development 3 Importance of Foundational Skills in Reading Instruction 5 Sight Word Instruction 7 III. Methods 10 Design 10 Participants 10 Instruments 11 Procedure 11 IV. Results 13 V. Discussion 16 References 20 List of Tables 1. t-test for Difference in Sample Mean Pretest Scores 13 2. t-test for Difference in Sample Mean Posttest Scores 14 3. t-test for Difference in Sample Mean Pre-to-Post Gains 15 i Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of sight word instruction on reading fluency for second grade students. The participants in this study were second grade students enrolled in a Baltimore County public school during the 2018-2019 school year. The students were randomly divided into two groups. The treatment group received small group guided instruction with a focus on sight word fluency four days a week for four weeks in addition to traditional whole group reading lessons. The control group received regular small group guided reading instruction and traditional whole group reading lessons. The results of the study indicated that both groups increased their reading levels, however, the hypothesis that sight word instruction would increase reading achievement was not supported when looking at the data. -

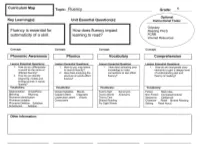

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

Research and the Reading Wars James S

CHAPTER 4 Research and the Reading Wars James S. Kim Controversy over the role of phonics in reading instruction has persisted for over 100 years, making the reading wars seem like an inevitable fact of American history. In the mid-nineteenth century, Horace Mann, the secre- tary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, railed against the teaching of the alphabetic code—the idea that letters represented sounds—as an imped- iment to reading for meaning. Mann excoriated the letters of the alphabet as “bloodless, ghostly apparitions,” and argued that children should first learn to read whole words) The 1886 publication of James Cattell’s pioneer- ing eye movement study showed that adults perceived words more rapidly 2 than letters, providing an ostensibly scientific basis for Mann’s assertions. In the twentieth century, state education officials like Mann have contin- ued to voice strong opinions about reading policy and practice, aiding the rapid implementation of whole language—inspired curriculum frameworks and texts during the late 1980s. And scientists like Cattell have shed light on theprocesses underlying skillful reading, contributing to a growing scientific 3 consensus that culminated in the 2000 National Reading Panel report. This chapter traces the history of the reading wars in both the political arena and the scientific community. The narrative is organized into three sections. The first offers the history of reading research in the 1950s, when the “conventional wisdom” in reading was established by acclaimed lead- ers in the field like William Gray, who encouraged teachers to instruct chil- dren how to read whole words while avoiding isolated phonics drills. -

Alphabetic Principle

Alphabetic Principle What is it? The alphabetic principle refers to the understanding that there are predictable and consistent relations between written letters and spoken sounds – the combination of letter knowledge and awareness. The 26 letters are the “key” to the English language. They have names, shapes, sounds, and go together to make words. Why is it important? Children's knowledge of letter names, shapes and sounds is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters. As this becomes internalized we will see writing and reading skills grow. Considerations: (what to think about?) • Be intentional with the purpose and clear with the expectations. “We are going to be learning about the letters of the alphabet. There are 26 letters (use the abc line to count together slowly while you touch them). You all have some of them in your names (check that out with their name cards). Letters have sounds and go together to make words. Your name is a word….” How cool is that!!” Make it interesting and meaningful. Revisit the learning often … “What letters do you know really well? Which ones are still tricky?” Kids can answer this! • Have 2 alphabet strips - one high to teach from and one low for students to access (have a special abc pointer to reach the high one when you teach from it). Have them run in one long line. • Be very explicit when talking about the alphabet and clear when enunciating. -

What Is a Lexile? Decatur County School System for Parents 2015-2016 Modified for WBE PTO Mtg

What is a Lexile? Decatur County School System For Parents 2015-2016 Modified for WBE PTO Mtg. (Jan. 2016) • A Lexile is a standard score that matches a student’s reading ability with difficulty of text material. • It is a measure of text complexity only. It does not address age-appropriateness of the content, or a reader’s interests. • A Lexile can be interpreted as the level of book that a student can read with 75% comprehension, offering the reader a certain amount of comfort and yet still offering a challenge. What is a Lexile? • K, 1st and 2nd Grade • Istation Reports provide Lexile scores • 3rd and 4th Grade: • Georgia Milestones Parent Reports provide Lexile scores Where do I find my student’s Lexile? • Lexile Targets by grade level are shown below. • College and Career Readiness – Goals for grade level CCRPI Grade Target 3 650 5 850 8 1050 11 1275 What does my student’s Lexile score tell me about his or her reading ability compared to other students in Georgia? • To calculate your student’s Lexile range, add 50 to the student’s reported Lexile score and subtract 100 (Example: 200 L = Range of 100-250L) • The range represents the boundaries between the easiest kind of reading material for your student and the hardest level at which he/she can read successfully. • Consider your child’s interest in topics and the age-appropriateness of the book’s content. Now that I know my student’s Lexile score, what do I do with it? A Quick Walk-Thru: Locating Books within Lexile Ranges @ https://lexile.com/ Enter Lexile Score How to Read a Book -

Reading Fluency

ß What is reading fluency? ß Why is fluency important? Reading ß What instruction helps students Fluency develop fluency? ß How can we adapt instruction for students with special needs? ß How can we monitor students’ progress in fluency? ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Fluency Instruction and Progress Monitoring 1 Fluency: reading quickly, accurately, and with expression ß Combines rate and accuracy ß Requires automaticity Fluency ß Includes reading with prosody Rate + Accuracy Fluency Comprehension ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Fluency Instruction and Progress Monitoring 2 Automaticity: ß Is quick, accurate recognition of letters and words Automaticity ß Frees cognitive resources to process meaning ß Is achieved through corrected practice ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Fluency Instruction and Progress Monitoring 3 What does fluent reading sound like? Fluent Reading . Fluent reading flows. It sounds smooth, with natural pauses. ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Fluency Instruction and Progress Monitoring 4 ß “Fluency provides a bridge between word recognition and comprehension.” —National Institute for Literacy (NIFL), Why Is 2001, p. 22 Reading ß Fluent readers are able to focus Fluency their attention on understanding Important? text. ß Because non-fluent readers focus much of their attention on figuring out words, they have less attention to devote to comprehension. ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Fluency Instruction and Progress Monitoring 5 What ß How to decode words (in isolation and in Students connected text) Need to ß How to automatically -

Reading, Spelling, and Language: Why There Is No Such Thing As a “Sight” Word

7/26/2018 Reading, Spelling, and Language: Why There is No Such Thing as a “Sight” Word DIBELS Super Summit July 9, 2018 Louisa Moats, Ed.D. 1 Topics For This Talk • Prevalence of beliefs about reading and spelling as “visual memory” activities • Common indicators of these beliefs in our classrooms • Review of evidence that orthographic memory relies on language processes and is only incidentally visual • Characteristics of instruction that are aligned with a linguistic theory of reading and spelling 2 Izzy, 2nd Grade Reading, 16th %ile Spelling, 12th %ile Vocabulary, 98th %ile 3 Louisa Moats, Ed.D., 2018 1 7/26/2018 How can teachers help Izzy? 4 Classroom Practices Reflecting the Belief That Reading is Primarily “Visual” • Vision therapy or colored overlays are often recommended when kids can’t read • High frequency words are treated as “sight words,” learned by rote repetition – 100 flash card words required in K – Texts written with high frequency words rather than with pattern-based words – Spelling taught by visual memory (write the word 10 times…) 5 Have You Seen This Conceptual Model of Word Recognition? Graphophonic/ Visual Semantic Syntactic “The Three Cueing Systems” 6 Louisa Moats, Ed.D., 2018 2 7/26/2018 How Reading and Spelling are Treated as “Visual” Skills • “Visual” cueing errors, along with meaning and structure errors, are a category in scoring Running Records • In the cueing systems model, the word “visual” is used interchangeably with “graphophonic” • Phonology has no role in the model 7 Everyday Practice: The Alphabetic -

Developing Early Literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel I

Developing Early Literacy REPORT OF THE NATIONAL EARLY LITERACY PANEL A Scientific Synthesis of Early Literacy Development and Implications for Intervention Developing Early Literacy REPORT OF THE NATIONAL EARLY LITERACY PANEL A Scientific Synthesis of Early Literacy Development and Implications for Intervention 2008 This publication was developed by the National Center for Family Literacy under a grant funded by Inter-agency agreement IAD-01-1701 and IAD-02-1790 between the Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institute for Literacy. It was peer reviewed and copy edited under a contract with RAND Corporation and designed under a contract with Graves Fowler Creative. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the policies of the National Institute for Literacy. No official endorsement by the National Institute for Literacy of any product, commodity, or enterprise in this publication is intended or should be inferred. The National Institute for Literacy, an agency in the Federal government, is authorized to help strengthen literacy across the lifespan. The Institute provides national leadership on literacy issues, including the improvement of reading instruction for children, youth, and adults by dissemination of information on scientifically based research and the application of those findings to instructional practice. Sandra Baxter, Director Lynn Reddy, Deputy Director The Partnership for Reading, a project administered by the National Institute for Literacy, is a collaborative effort of the National Institute for Literacy, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the U.S. Department of Education, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to make scientifically based reading research available to educators, parents, policy makers, and others with an interest in helping all people learn to read well.