The End of Illiteracy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the Key Concept to Its Definition by Writing the Letter in the Correct Blank

AP HANDOUT 2A Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the key concept to its definition by writing the letter in the correct blank. Set A 1. ______ decoding A. Understanding that the sequence of letters in written words represents the sequence of sounds (or phonemes) in spoken words 2. ______common sound B. Sound that a letter most frequently makes in a word 3. ______decodable texts C. Vowels and certain consonant sounds that can be prolonged during pronunciation and are easier to say without being distorted 4. ______ encoding D. Engaging and coherent texts in which most of the words are comprised of an accumulating sequence of letter-sound correspondences being taught 5. ______ alphabetic E. Process of converting printed words into their spoken principle forms by using knowledge of letter-sound relationships and word structure 6. ______ continuous F. Process of converting spoken words into their written sounds forms (spelling) SET B 7. ______ sounding out G. Words in which some or all of the letters do not represent their most common sounds 8. ______ letter H. Groups of consecutive letters that represent a particular recognition sound(s) in words 9. ______ irregular words I. Ability to distinguish and name each letter of the alphabet, sequence the letters, and distinguish and produce both upper and lowercase letters 10. ______ regular words J. Relationships between common sounds of letters or letter combinations in written words 11. ______ stop sounds K. Words in which the letters make their most common sound 12. ______ letter-sound L. Process of saying each sound that represents a letter(s) in correspondences a word and blending them together to read it 13. -

Beginning Reading: Influences on Policy in the United

BEGINNING READING: INFLUENCES ON POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES AND ENGLAND 1998-2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Education of Aurora University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education by Elizabeth Robins April 2010 Beginning Reading: Influences on Policy in the United States and England 1998-2010 by Elizabeth Robins [email protected] Committee members: Ronald Banaszak, Chair Carla Brown, Member Deborah Brotcke, Member Abstract The study investigated the divergence in beginning reading methods between the United States (US) and England from 1998 to 2010. Researchers, policy makers, and publishers were interviewed to explore their knowledge and perceptions concerning how literacy policy was determined. The first three of twelve findings showed that despite the challenges inherent in the political sphere, both governments were driven by low literacy rates to seek greater involvement in literacy education. The intervention was determined by its structure: a central parliamentary system in England, and a federal system of state rights in the US. Three further research-related findings revealed the uneasy relationship existing between policy makers and researchers. Political expediency, the speed of decision making and ideology i also helped shape literacy policy. Secondly, research is viewed differently in each nation. Peer- reviewed, scientifically-based research supporting systematic phonics prevailed in the US, whereas in England additional and more eclectic sources were also included. Thirdly, research showed that educator training in beginning reading was more pervasive and effective in England than the US. English stakeholders proved more knowledgeable about research in the US, whereas little is known about the synthetic phonics approach currently used in England. -

Janet and John: Here We Go Free Download

JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO FREE DOWNLOAD Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series Toral Taank rated it it was amazing Nov 29, All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Visit my eBay shop. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Shelves: beginner-readersfemale-author-or- illustrator. Hardcover40 pages. Reminiscing Read these as a child, Janet and John: Here We Go use with my Grandbabies X Previous image. Books by Mabel O'Donnell. No doubt, Janet and John: Here We Go critics will carp at the daringly minimalist plot and character de In a recent threadsome people stated their objections to literature which fails in its duty to be gender-balanced. Please enter a number less than or equal to Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Watch this item Unwatch. Novels portal Children's literature portal. Janet and John: Here We Go O'Donnell and Rona Munro. Ronne Randall. Learning to read. Inas part of a trend in publishing nostalgic facsimiles of old favourites, Summersdale Publishers reissued two of the original Janet and John books, Here We Go and Off to Play. Analytical phonics Basal reader Guided reading Independent reading Literature circle Phonics Reciprocal teaching Structured word inquiry Synthetic phonics Whole language. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. -

Introduction

1 Introduction Phonics instruction has long been a controversial matter. Emans (1968) points out that the emphasis on phonics instruction has changed several times over the past two centuries. Instruction has shifted from one extreme—no phonics instruction— to the other—phonics instruction as the major method of word-recognition instruction—and back again. Emans also points out that “each time that phonics has been returned to the classroom, it usually has been revised into something quite different from what it was when it was discarded” (p. 607 ). Currently, most beginning reading programs include a significant component of phonics instruc- tion. This is especially true since the implementation of policies related to the No Child Left Behind Act and recommendations by the National Reading Panel (2000) for the use of both instruction and assessments related to explicit pho- nics instruction. It is also likely that the U.S. Department of Education’s initiative Race to the Top, funded as part of the Education Recovery Act of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (AARA), will continue to view phonics instruction as an integral component and focus of reading instruction. Phonics, however, is not the cure-all for reading ills that some believe it to be. Rudolph Flesch’s book Why Johnny Can’t Read (1955), although it did bring the phonics debate to the attention of the public, typifies the kind of literature that takes a naive approach to a complex problem. As Heilman (1981) points out, “Flesch’s suggestions for teaching were quite primitive, consisting pri- marily of lists of words each presenting different letter-sound patterns. -

Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Hempenstall, K

Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Hempenstall, K. (No date). Some issues in phonics instruction. Education News 26/2/2001. [On-line]. Available: http://www.educationnews.org/some_issues_in_phonics_instructi.htm There are essentially two approaches to teaching phonics that influence what is taught: implicit and explicit phonics instruction. What is the difference? In an explicit (synthetic) program, students will learn the associations between the letters and their sounds. This may comprise showing students the graphemes and teaching them the sounds that correspond to them, as in “This letter you are looking at makes the sound sssss”. Alternatively, some teachers prefer teaching students single sounds first, and then later introducing the visual cue (the grapheme) for the sound, as in “You know the mmmm sound we’ve been practising, well here’s the letter used in writing that tells us to make that sound”. In an explicit program, the processes of blending (What word do these sounds make when we put them together mmm-aaa-nnn?”), and segmenting (“Sound out this word for me”) are also taught. It is of little value knowing what are the building blocks of our language’s structure if one does not know how to put those blocks together appropriately to allow written communication, or to separate them to enable decoding of a letter grouping. After letter-sound correspondence has been taught, phonograms (such as: er, ir, ur, wor, ear, sh, ee, th) are introduced, and more complex words can be introduced into reading activities. In conjunction with this approach "controlled vocabulary" stories may be used - books using only words decodable using the students' current knowledge base. -

Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 479 530 CS 512 338 AUTHOR Pearson, P. David TITLE Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-08-00 NOTE 46p.; CIERA Archive #01-08. CONTRACT R305R70004 AVAILABLE FROM CIERA/University of Michigan, 610 E. University Ave., 1600 SEB, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259. Tel: 734-647-6940; Fax: 734- 763 -1229. For full text: http://www.ciera.org/library/archive/ 2001-08/0108pdp.pdf. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070). Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Futures (of Society); Instructional Materials; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Processes; *Reading Research; Reading Skills; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Reading Theories ABSTRACT This paper discusses reading instruction in the 20th century. The paper begins with a tour of the historical pathways that have led people, at the century's end, to the "rocky and highly contested terrain educators currently occupy in reading pedagogy." After the author/educator unfolds his version of a map of that terrain in the paper, he speculates about pedagogical journeys that lie ahead in a new century and a new millennium. Although the focus is reading pedagogy, the paper seeks to connect the pedagogy to the broader scholarly ideas of each period. According to the paper, developments in reading pedagogy over the last century suggest that it is most useful to divide the century into thirds, roughly 1900-1935, 1935- 1970, and 1970-2000. The paper states that, as a guide in constructing a map of past and present, a legend is needed, a common set of criteria for examining ideas and practices in each period--several candidates suggest themselves, such as the dominant materials used by teachers in each period and the dominant pedagogical practices. -

The Effect of Teaching Phonics and Phonemic Awareness Training To

The Effect of Teaching Phonics and Phonemic Awareness Training to Adolescent Struggling Readers by Stephanie Hardesty Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education December 2013 Goucher College Graduate Programs in Education Table of Contents List of Tables i Abstract ii I. Introduction 1 Statement of the Problem 2 Hypothesis 3 Operational Definitions 3 II. Literature Review 6 Phonemic Awareness Training and Phonics 6 Reading Instruction in the High School Setting 7 Reading Remediation 10 Summary 13 III. Methods 14 Participants 14 Instrument 15 Procedure 16 IV. Results 19 V. Discussion 20 Implications 20 Threats to Validity 21 Comparison to Previous Studies 22 Suggestions for Future Research 24 References 25 List of Tables 1. Pre- and Post-SRI Test Results 19 i Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of teaching phonics and phonemic awareness training to adolescent struggling readers. The measurement tool was the Scholastic Reading Inventory (SRI). This study involved the use of a pretest/posttest design to compare data prior to the implementation of the reading intervention, System 44, to data after the intervention was complete (one to two years). Achievement gains were not significant, though results could be attributable to a number of intervening factors. Research in the area of high school reading remediation should continue given the continued disagreement over best practices and the new standards that must be met per the Common Core. ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Advanced or proficient reading abilities are one of the primary yet essential skills that should be mastered by every student. -

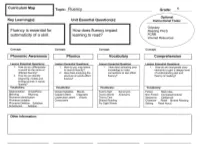

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

Alphabetic Principle

Alphabetic Principle What is it? The alphabetic principle refers to the understanding that there are predictable and consistent relations between written letters and spoken sounds – the combination of letter knowledge and awareness. The 26 letters are the “key” to the English language. They have names, shapes, sounds, and go together to make words. Why is it important? Children's knowledge of letter names, shapes and sounds is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters. As this becomes internalized we will see writing and reading skills grow. Considerations: (what to think about?) • Be intentional with the purpose and clear with the expectations. “We are going to be learning about the letters of the alphabet. There are 26 letters (use the abc line to count together slowly while you touch them). You all have some of them in your names (check that out with their name cards). Letters have sounds and go together to make words. Your name is a word….” How cool is that!!” Make it interesting and meaningful. Revisit the learning often … “What letters do you know really well? Which ones are still tricky?” Kids can answer this! • Have 2 alphabet strips - one high to teach from and one low for students to access (have a special abc pointer to reach the high one when you teach from it). Have them run in one long line. • Be very explicit when talking about the alphabet and clear when enunciating. -

A Dissertation Entitled the Effects of an Orton-Gillingham-Based

A Dissertation entitled The Effects of an Orton-Gillingham-based Reading Intervention on Students with Emotional/Behavior Disorders by James Breckinridge Davis, M.Ed. Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Special Education. Richard Welsch, Ph.D., Committee Chair Laurie Dinnebeil, Ph.D., Committee Member Edward Cancio, Ph.D., Committee Member Lynne Hamer, Ph.D., Committee Member Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Ph.D., Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2011 Copyright. 2011, James Breckinridge Davis This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of The Effects of an Orton-Gillingham-based Reading Intervention on Students with Emotional/Behavior Disorders by James Breckinridge Davis, M.Ed. Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Special Education. The University of Toledo December 2011 This study was performed with 4 male students enrolled in a specialized public school for students with emotional/behavior disorders (E/BD). All of the students participated in a 16-week, one-to-one, multisensory reading intervention. The study was a single subject, multiple baseline design. The independent variable was an Orton- Gillingham-based reading intervention for 45 minute sessions. The dependent variable was the students‘ performance on daily probes of words read correctly and the use of pre- and post-test measures on the Dynamic Indicator of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS). The intervention consisted of 6 different parts: (a) visual, (b) auditory, (c) blending, (d) introduction of a new skill, (e) oral reading, and (f) 10-point probe. -

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research The alphabetic principle is composed of two parts: • Alphabetic Understanding: Words are composed of letters that represent sounds. • Phonological Recoding: Using systematic relationships between letters and phonemes (letter-sound correspondence) to retrieve the pronunciation of an unknown printed string or to spell words. Phonological recoding consists of: o Regular Word Reading o Irregular Word Reading o Advanced Word Analysis Regular Word Reading A regular word is a word in which all the letters represent their most common sounds. Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded). Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1997). Beginning decoding ("phonological recoding") is the ability to: • read from left to right, simple, unfamiliar regular words. • generate the sounds for all letters. • blend sounds into recognizable words. Beginning spelling is the ability to: • translate speech to print using phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter-sounds. Progression of Regular Word Reading Skills Sight Word Sounding Saying the Reading Automatic Out Whole Word (sounding out Word (saying (saying each the word in your Reading each individual sound head, if (reading the individual and pronouncing necessary, and word without sound out the whole word) saying the sounding it -

Teaching Children to Read

House of Commons Education and Skills Committee Teaching Children to Read Eighth Report of Session 2004–05 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 21 March 2005 HC 121 Incorporating HC 1269–i from Session 2003-04 Published on 7 April 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £22.00 The Education and Skills Committee The Education and Skills Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Education and Skills and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Barry Sheerman MP (Labour, Huddersfield) (Chairman) Mr David Chaytor MP (Labour, Bury North) Valerie Davey MP (Labour, Bristol West) Jeff Ennis MP (Labour, Barnsley East & Mexborough) Mr Nick Gibb MP (Conservative, Bognor Regis & Littlehampton) Mr John Greenway MP (Conservative, Ryedale) Paul Holmes MP (Liberal Democrat, Chesterfield) Helen Jones MP (Labour, Warrington North) Mr Kerry Pollard MP (Labour, St Albans) Jonathan Shaw MP (Labour, Chatham and Aylesford) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at: www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/education_and_skills_committee.cfm Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are David Lloyd (Clerk), Dr Sue Griffiths (Second Clerk), Libby Aston (Committee Specialist), Nerys Roberts (Committee Specialist), Lisa Wrobel (Committee Assistant), Susan Monaghan (Committee Assistant), Catherine Jackson (Secretary) and John Kittle (Senior Office Clerk).