Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginning Reading: Influences on Policy in the United

BEGINNING READING: INFLUENCES ON POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES AND ENGLAND 1998-2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Education of Aurora University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education by Elizabeth Robins April 2010 Beginning Reading: Influences on Policy in the United States and England 1998-2010 by Elizabeth Robins [email protected] Committee members: Ronald Banaszak, Chair Carla Brown, Member Deborah Brotcke, Member Abstract The study investigated the divergence in beginning reading methods between the United States (US) and England from 1998 to 2010. Researchers, policy makers, and publishers were interviewed to explore their knowledge and perceptions concerning how literacy policy was determined. The first three of twelve findings showed that despite the challenges inherent in the political sphere, both governments were driven by low literacy rates to seek greater involvement in literacy education. The intervention was determined by its structure: a central parliamentary system in England, and a federal system of state rights in the US. Three further research-related findings revealed the uneasy relationship existing between policy makers and researchers. Political expediency, the speed of decision making and ideology i also helped shape literacy policy. Secondly, research is viewed differently in each nation. Peer- reviewed, scientifically-based research supporting systematic phonics prevailed in the US, whereas in England additional and more eclectic sources were also included. Thirdly, research showed that educator training in beginning reading was more pervasive and effective in England than the US. English stakeholders proved more knowledgeable about research in the US, whereas little is known about the synthetic phonics approach currently used in England. -

Janet and John: Here We Go Free Download

JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO FREE DOWNLOAD Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series Toral Taank rated it it was amazing Nov 29, All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Visit my eBay shop. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Shelves: beginner-readersfemale-author-or- illustrator. Hardcover40 pages. Reminiscing Read these as a child, Janet and John: Here We Go use with my Grandbabies X Previous image. Books by Mabel O'Donnell. No doubt, Janet and John: Here We Go critics will carp at the daringly minimalist plot and character de In a recent threadsome people stated their objections to literature which fails in its duty to be gender-balanced. Please enter a number less than or equal to Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Watch this item Unwatch. Novels portal Children's literature portal. Janet and John: Here We Go O'Donnell and Rona Munro. Ronne Randall. Learning to read. Inas part of a trend in publishing nostalgic facsimiles of old favourites, Summersdale Publishers reissued two of the original Janet and John books, Here We Go and Off to Play. Analytical phonics Basal reader Guided reading Independent reading Literature circle Phonics Reciprocal teaching Structured word inquiry Synthetic phonics Whole language. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. -

Scientific Evidence for Effective Teaching of Reading

Read About It: Scientific Evidence for Effective Teaching of Reading Kerry Hempenstall Edited by Jennifer Buckingham Research Report | March 2016 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Creator: Hempenstall, Kerry, author. Title: Read about it : scientific evidence for effective teaching of reading / Kerry Hempenstall ; edited by Jennifer Buckingham. ISBN: 9781922184610? (paperback) Series: CIS research report ; 11. Subjects: Effective teaching. Early childhood education--Research--Australia. Literacy--Research--Australia. Teacher effectiveness. Other Creators/Contributors: Buckingham, Jennifer, editor. Centre for Independent Studies (Australia), issuing body. Dewey Number: 371.10994 Read About It: Scientific Evidence for Effective Teaching of Reading Kerry Hempenstall Edited by Jennifer Buckingham Research Report 11 Related CIS publications Research Report RR9 Jennifer Buckingham and Trisha Jha, One School Does Not Fit All (2016) Policy Magazine Spring Issue Jennifer Buckingham, Kevin Wheldall and Robyn Beaman-Wheldall, ‘Why Jaydon can’t read: The triumph of ideology over evidence in teaching reading’ (2013) Contents Executive Summary ...............................................................................................1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................3 The power of improved instruction ...................................................................4 Effective, evidence-based reading instruction: The five ‘keys’ -

Introduction

1 Introduction Phonics instruction has long been a controversial matter. Emans (1968) points out that the emphasis on phonics instruction has changed several times over the past two centuries. Instruction has shifted from one extreme—no phonics instruction— to the other—phonics instruction as the major method of word-recognition instruction—and back again. Emans also points out that “each time that phonics has been returned to the classroom, it usually has been revised into something quite different from what it was when it was discarded” (p. 607 ). Currently, most beginning reading programs include a significant component of phonics instruc- tion. This is especially true since the implementation of policies related to the No Child Left Behind Act and recommendations by the National Reading Panel (2000) for the use of both instruction and assessments related to explicit pho- nics instruction. It is also likely that the U.S. Department of Education’s initiative Race to the Top, funded as part of the Education Recovery Act of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (AARA), will continue to view phonics instruction as an integral component and focus of reading instruction. Phonics, however, is not the cure-all for reading ills that some believe it to be. Rudolph Flesch’s book Why Johnny Can’t Read (1955), although it did bring the phonics debate to the attention of the public, typifies the kind of literature that takes a naive approach to a complex problem. As Heilman (1981) points out, “Flesch’s suggestions for teaching were quite primitive, consisting pri- marily of lists of words each presenting different letter-sound patterns. -

Week 3 Resources, Comprehension

Meaning Skills PLC Week 3 Resources, Comprehension Resources Within in the Lesson Additional Reading Resources Additional Links and Websites **Chapter 7 of Applying **Inspire a Life of Reading: Lesson You can use the CCRS- Research in Reading Plans to Engage Adult Beginning Lexile Correlation chart to Instructions for Adults by Susan Readers by Cheryl Knight, help you know what level McShane Appalachian State University is best suited for your This chapter of McShane's book This manual includes activities in learners. focuses on the topic of the areas of assessment, comprehension. There are also phonemic awareness, word Lexile.com is a nice site a few sample activities for analysis, fluency, vocabulary, and fluency. comprehension. Activities are that you can paste or type complete with goals and a text into in order to get The National Reading Panel objectives, directions, handouts, the lexile level. Subgroup Report on Fluency game boards, and materials lists. This report contains an All activities are correlated with Here is a link for question executive summary from each reading competencies and are stems for all of the CCRS subgroup that introduces the appropriate for individuals, teams, reading anchors topic area, outlines the group's or large groups. For lesson plans methodology, and highlights the incorporating comprehension, see Watch this video from a questions and results from each p. 89-156; for lesson plans California adult reading subgroup. This is an excellent incorporating relia (i.e. use of real- class for an example of a resource for anyone who wishes life documents/contextualized think aloud integrated into to understand the science and lessons), see p. -

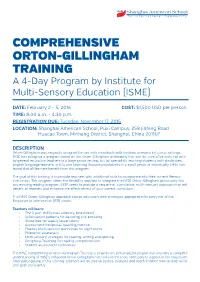

COMPREHENSIVE ORTON-GILLINGHAM TRAINING a 4-Day Program by Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (ISME)

Shanghai American School An International Community COMPREHENSIVE ORTON-GILLINGHAM TRAINING A 4-Day Program by Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (ISME) DATE: February 2 - 5, 2016 COST: $1,500 USD per person TIME: 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. REGISTRATION DUE: Tuesday, November 17, 2015 LOCATION: Shanghai American School, Puxi Campus, 258 Jinfeng Road Huacao Town, Minhang District, Shanghai, China 201107 DESCRIPTION Orton-Gillingham was originally designed for use with individuals with dyslexia primarily in tutorial settings. IMSE has designed a program based on the Orton-Gillingham philosophy that can be used effectively not only by general education teachers in a large group setting, but by specialists teaching students with disabilities, English language learners, or EAL and Learning Support populations in a small group or individually. IMSE has found that all learners benefit from this program. The goal of this training is to provide teachers with additional tools to incorporate into their current literacy instruction. This program offers the flexibility required to integrate the IMSE Orton-Gillingham philosophy into any existing reading program. IMSE seeks to provide a sequential, cumulative, multi-sensory approach that will benefit all learners and enhance the effectiveness of your current curriculum. The IMSE Orton-Gillingham approach equips educators with strategies appropriate for every tier of the Response to Intervention (RTI) model. Teachers will learn: • The 3-part drill (visual, auditory, kinesthetic) • Syllabication patterns for decoding and encoding • Guidelines for weekly lesson plans • Assessment Reciprocal Teaching method • Fluency Multi-sensory techniques for sight words • Phonemic awareness • Multi-sensory strategies for reading, writing and spelling • Reciprocal Teaching for reading comprehension • Student assessment techniques The IMSE Comprehensive Orton-Gillingham Training is a hands-on, personalized session that provides a complete understanding of IMSE’s enhanced Orton-Gillingham method and the tools necessary to apply it in the classroom. -

Literacy Perspectives

Vol.2, No.4 Winter/Spring 1998 CC-VI FORUM Comprehensive Regional Assistance Center Consortium—Region VI LITERACY PERSPECTIVES The Great Debate? From Walter Secada, Ph.D. Comprehensive Regional Assistance Center by Walter Secada, Ph.D. Consortium–RegionVI eading is one of the most important cur- As many of you know, riculum goals for the primary grades. A Minerva Coyne retired from R U. S. Department of Education prior- the University of Wisconsin– ity and national educational goal is that all stu- Madison this past October at dents read well by the end of third grade. In which time, I took over as the fourth grade, students are expected to “read to learn.” Reading instruction is heavily Regional Director. Minerva funded under Title I and other Titles of will be a very hard act to fol- Improving America’s Schools Act. low. She was truly committed How to best teach reading is one of the to improving our children’s most hotly debated topics among researchers, education and the professional educators, parents, and the general public. An lives of teachers. In addition, esprit simpliste has dominated the public policy debate, pitting phonics against whole language. she recruited a first rate staff and group of collabo- Such simplification makes for sharp debates rators to help the Center meet its mission. fraught with symbolic politics. Proponents of By way of self-introduction, I am a Professor of basic skills rally round the flag of phonics, Curriculum and Instruction at the University of painting supporters of whole language meth- Wisconsin–Madison. Many of you may remember me ods as lacking disciplinary values—both, educa- from when I directed a Multifunctional Resource tional and moral values it would seem, given INSIDE the shrill tenor of these debates. -

INFORMATION CAPSULE Research Services

Miami-Dade County Public Schools giving our students the world INFORMATION CAPSULE Research Services Vol. 0609 Christie Blazer, Supervisor March 2007 RECIPROCAL TEACHING At A Glance Reciprocal teaching is an instructional approach designed to increase students’ reading comprehension at all grade levels and in all subject areas. Students are taught cognitive strategies that help them construct meaning from text and simultaneously monitor their reading comprehension. This Information Capsule summarizes reciprocal teaching’s basic principles, implementation steps, and four comprehension strategies. Issues to consider when implementing reciprocal teaching are discussed, including how to teach the strategies, what grade levels and types of students benefit from reciprocal teaching, and optimum group size. Research on the impact of reciprocal teaching on students’ reading comprehension is reviewed and a brief summary of Miami-Dade County Public Schools’ use of reciprocal teaching is provided. Little progress has been made nationwide toward improving students’ reading skills during the past decade, as evidenced by minimal improvements in reading scores on the Nation’s Report Card, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The table below shows that the 2005 average NAEP grade 4 reading scale score was one point higher than the 2003 average score and two points higher than the 1992 average score (on a 500-point scale). In eighth grade, the 2005 average reading score was one point lower than the 2003 average score and two points higher than the 1992 average score. Grades 4 and 8 NAEP Reading Scale Scores, 1992, 2003, and 2005 300 275 260 263 262 Grade 8 250 225 217 218 219 Grade 4 200 175 1992 2003 2005 Source: National Center for Education Statistics, 2005. -

The End of Illiteracy?

The End of Illiteracy? The Holy Grail of Clackmannanshire TOM BURKARD CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 1999 THE AUTHOR Tom Burkard is the Secretary of the Promethean Trust and has published several articles on how children learn to read. He contributed to the 1997 Daily Telegraph Schools Guide, and is a member of the NASUWT. His main academic interest is the interface between reading theory and classroom practice. His own remedial programme, recently featured in the Dyslexia Review, achieved outstanding results at Costessey High School in Norwich. His last Centre for Policy Study pamphlet, Reading Fever: Why phonics must come first (written with Martin Turner in 1996) proved instrumental in determining important issues in the National Curriculum for teacher training colleges. Acknowledgements Support towards research for this Study was given by the Institute for Policy Research. The Centre for Policy Studies never expresses a corporate view in any of its publications. Contributions are chosen for their independence of thought and cogency of argument. ISBN No. 1 897969 87 2 Centre for Policy Studies, March 1999 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 - 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. A brief history of the ‘reading wars’ 4 3. A comparison of analytic and synthetic phonics 9 4. Problems with the National Literacy Strategy 12 5. The success of synthetic phonics 17 6. Introducing synthetic phonics into the classroom 20 7. Recommendations 22 Appendix A: Problems with SATs 25 Appendix B: A summary of recent research on analytic phonics 27 Appendix C: Research on the effectiveness of synthetic phonics 32 SUMMARY The Government’s recognition of the gravity of the problem of illiteracy in Britain is welcome. -

Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Hempenstall, K

Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Hempenstall, K. (No date). Some issues in phonics instruction. Education News 26/2/2001. [On-line]. Available: http://www.educationnews.org/some_issues_in_phonics_instructi.htm There are essentially two approaches to teaching phonics that influence what is taught: implicit and explicit phonics instruction. What is the difference? In an explicit (synthetic) program, students will learn the associations between the letters and their sounds. This may comprise showing students the graphemes and teaching them the sounds that correspond to them, as in “This letter you are looking at makes the sound sssss”. Alternatively, some teachers prefer teaching students single sounds first, and then later introducing the visual cue (the grapheme) for the sound, as in “You know the mmmm sound we’ve been practising, well here’s the letter used in writing that tells us to make that sound”. In an explicit program, the processes of blending (What word do these sounds make when we put them together mmm-aaa-nnn?”), and segmenting (“Sound out this word for me”) are also taught. It is of little value knowing what are the building blocks of our language’s structure if one does not know how to put those blocks together appropriately to allow written communication, or to separate them to enable decoding of a letter grouping. After letter-sound correspondence has been taught, phonograms (such as: er, ir, ur, wor, ear, sh, ee, th) are introduced, and more complex words can be introduced into reading activities. In conjunction with this approach "controlled vocabulary" stories may be used - books using only words decodable using the students' current knowledge base. -

Practices News SARA G

Direct Instruction Effective School Practices news SARA G. TARVER, Editor, University of Wisconsin, Madison that cognitive scientists have deter- Practice: A Key to Success mined beyond any shadow of a doubt that students will only remember what they have practiced extensively and that they will remember for the long The number of DI success stories con- to all members of ADI, and indeed to term only that which they have prac- tinues to grow. This issue of DI News all who seek excellence in education, ticed in a sustained way over many includes (a) the stories of two schools by writing many articles about DI and years. This article supports Zig’s long- that received Wesley Becker Excellent generously sharing his many reference standing insistence on firming, firm- School Awards at the 2004 ADI Con- lists with those who seek references for ing, firming and mastery, mastery, ference—Buford Elementary School in various purposes. When you want to mastery. It also highlights the impor- Buford, Georgia and Eisenhut Elemen- find out what is known about a particu- tance of a particular feature of all DI tary School in Modesto, California; (b) lar topic related to DI, just ask Kerry. programs—massed to distributed prac- the story of Mountain View Academy tice. Intensive massed practice of new in Greeley, Colorado; and (c) the sto- All of these success stories rest on the ries of three schools that received shoulders of a group of Oregon profes- continued on page 3 Golden Apple Awards from Educa- sors who have been instrumental in tional Resources, Inc. -

'Simple View of Reading Model'

The Simple View of Reading Language comprehension processes G O O D Poor word decoding Good word decoding Good comprehension Good comprehension Word Word decoding/recognition P O O R G O O D decoding/recognition processes processes Poor word decoding Good word decoding Poor comprehension Poor comprehension P O O R Language comprehension processes Simple View of Reading model: Original concept ‐ Gough and Tunmer (1986), recommended by Jim Rose (Final Report, March 2006) Adopted by UK government (2006) as a useful conceptual framework: reading = decoding x compehension R = D x C Use for training; and a broad analysis of pupils’ profiles for next steps planning and monitoring over time. Colour‐code and date entries. For pupils with English as an additional or new language, plot for English and for the first language. Copyright Phonics International Ltd 2012 The Simple View of Writing Composition: articulating and structuring ideas G O O D Poor transcription Good transcription Good composition Good composition Transcription: Transcription: spelling P O O R G O O D spelling handwriting handwriting Poor transcription Good transcription Poor composition Poor composition P O O R Composition: articulating and structuring ideas Simple View of Writing model: Adaptation of the SVoR model (Gough and Tunmer 1986) by Debbie Hepplewhite – for training, analysis and planning. Note: Spelling includes: knowledge of the alphabetic code (spelling alternatives) and encoding skill, high‐frequency tricky words, spelling word banks, etymology (word origins), morphology (word structures), some spelling rules. ‘Teach pupils to plan, revise and evaluate their writing – knowledge which is not required for reading’ (DfE National Curriculum for English, Key Stages 1 and 2 – Draft, 2012).