Defending Whole Language: the Limits of Phonics Instruction and the Efficacy of Whole Language Instruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Literature Across the First Grade Curriculum Through Thematic Units

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1992 Integrating literature across the first grade curriculum through thematic units Diana Gomez-Schardein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Education Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Gomez-Schardein, Diana, "Integrating literature across the first grade curriculum through thematic units" (1992). Theses Digitization Project. 710. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/710 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. California State University San Bernardino INTEGRATING LITERATURE ACROSS THE FIRST GRADE CURRICULUM THROUGH THEMATIC UNITS A Project Submitted to The Faculty of the School ofEducation In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts in Education: Reading Option By Diana Gomez-Schardein,M.A. San Bernardino, California 1992 APPROVED BY: Advisor : Dr. Adrla Klein eco/id#{eader : Mr. Jcfe Gray I I SUMMARY Illiteracy is one of the nation's eminent problems. Ongoing controversy exists among educators as to how to best combat this problem of growing proportion. The past practice has been to teach language and reading in a piecemeal,fragmented manner. Research indicates, however,curriculum presented as a meaningful whole is more apt to facilitate learning. The explosion of marvelous literature for children and adolescents provides teachers with the materials necessary for authentic reading programs. -

Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials

Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts Volume 49 Issue 1 October/November 2008 Article 4 10-2008 Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials Arlene Barry Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Barry, A. (2008). Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 49 (1). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol49/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Education and Literacy Studies at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. Reading the Past • 31 Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials Arlene L. Barry, Ph.D. University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas Abstract This article addresses the International Reading Association’s foun- dational knowledge requirement that educators recognize histori- cal antecedents to contemporary reading methods and materials. The historical overview presented here highlights the ineffective methods and restrictive materials that have been discarded and the progress that has been made in the development of more effective and inclusive reading materials. In addition, tributes are paid to seldom-recognized innovators whose early efforts to improve read- ing instruction for their own students resulted in important change still evident in materials used today. Why should an educator be interested in the history of literacy? It has been frequently suggested that knowing history allows us to learn from the past. -

What Is Phonics? Adapted From: Elish-Piper L

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY | JERRY L. JOHNS LITERACY CLINIC Raising Readers: Tips for Parents What is Phonics? Adapted from: Elish-Piper L. (2009/2010). Information and Ideas for parents about phonemic awareness and phonics. Illinois Reading Council Journal, 31(1), 52-54 Phonics is the relationship between letters and sounds. Children usually learn beginning sounds first, short vowels Readers use phonics to decode or sound out unknown next and then three letter words such as “cat,” “sit” and words. For example, when a reader comes to a word they “map.” Next, children learn about the silent “e” that comes don’t know, they can decode the word letter by letter such as at the end of words and makes a vowel a long vowel, meaning in the example “big” where they would identify the sounds that the vowel says its own name such as /a/ in the word /b/ /i/ /g/ to read the word “big.” Other words may have “tape.” Children also learn about other long vowel patterns as chunks or patterns that they can use to figure out unknown well as blends such as the letters /tr/ /br/ and /cl/. words. For example, when they come to the word “jump” Even if parents do not understand all of the phonics rules and they may identify the sound /j/ and then the familiar chunk patterns, they can still help their children develop phonics /ump/ that they knows from other words such as “bump,” skills. Here are 10 fun, easy activities that parents and “lump” and “dump.” children can do to practice phonics skills at home. -

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

Comparing the Word Processing and Reading Comprehension of Skilled and Less Skilled Readers

Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice - 12(4) • Autumn • 2822-2828 ©2012 Educational Consultancy and Research Center www.edam.com.tr/estp Comparing the Word Processing and Reading Comprehension of Skilled and Less Skilled Readers İ. Birkan GULDENOĞLU Tevhide KARGINa Paul MILLER Ankara University Ankara University University of Haifa Abstract The purpose of this study was to compare the word processing and reading comprehension skilled in and less skilled readers. Forty-nine, 2nd graders (26 skilled and 23 less skilled readers) partici- pated in this study. They were tested with two experiments assessing their processing of isolated real word and pseudoword pairs as well as their reading comprehension skills. Findings suggest that there is a significant difference between skilled and less skilled readers both with regard to their word processing skills and their reading comprehension skills. In addition, findings suggest that word processing skills and reading comprehension skills correlate positively both skilled and less skilled readers. Key Words Reading, Reading Comprehension, Word Processing Skills, Reading Theories. Reading is one of the most central aims of school- According to the above mentioned phonologi- ing and all children are expected to acquire this cal reading theory, readers first recognize written skill in school (Güzel, 1998; Moates, 2000). The words phonologically via their spoken lexicon and, ability to read is assumed to rely on two psycho- subsequently, apply their linguistic (syntactic, se- linguistic processes: -

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language Academic Areas of Concern Students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) have severe trouble learning or demonstrating skills in one or more of these academic areas: oral expression reading fluency listening comprehension reading comprehension written expression mathematics calculation and basic reading skill mathematics problem solving Students with SLD often do well in some school subjects but have extreme difficulty with skills like decoding (sounding out) words, calculating math facts, or writing down their thoughts. Even with adequate instruction and intensive intervention, a student with SLD has low classroom achievement when compared to students without disabilities in the same grade. Specific information about how the student has responded to instruction and intensive intervention is used to decide if a student is SLD or if the student is not achieving for other reasons. Referral for Special Education When someone thinks a student might have any disability and needs special education, a referral for a special education evaluation is made to the school. The referral must be in writing and say why the person making the referral thinks the student has a disability. A group of people, called an IEP team, which includes the student’s parents, does an evaluation and decides if the student meets state and federal criteria. Three Criteria to Meet The three criteria (requirements) below must be considered by the IEP team and all 3 of them must be met in order to decide the student has SLD. 1. Inadequate Classroom Achievement - This means a student's academic skills in one or more academic areas of concern are well outside the expected range for students without disabilities of the same age. -

The Synthetic Phonics Teaching Principles June 2015

The Synthetic Phonics Teaching Principles June 2015 Teach the relationship between sounds and letters by systematically introducing the letter/s-sound correspondences of the English alphabetic code (e.g. between three and five correspondences per week at first, including vowels and consonants). Start with mainly one spelling for each of the 42+ sounds (phonemes) identifiable in English speech before broadening out to focus on further spelling and pronunciation variations. (Initial teaching takes 2 to 3 years to teach a comprehensive level of alphabetic code; continue to build on this as required for phonics for spelling.) Model how to put the letter/s-sound correspondences introduced (the alphabetic code knowledge) to immediate use teaching the three skills of: Reading/decoding: synthesise (sound out and blend) all-through-the-printed-word to ‘hear’ the target word. Modify the pronunciation of the word where necessary. Spelling/encoding: orally segment (split up) all-through-the-spoken-word to identify the single sounds (phonemes) and know which letters and letter groups (graphemes) are code for the identified sounds. Handwriting: write the lower case, then the upper case, letters of the alphabet correctly. Hold the pencil with a tripod grip. Practise regular dictation exercises from letter level to text level (as appropriate). Provide cumulative, decodable words, sentences and texts which match the level of alphabetic code knowledge and blending skills taught to date, when asking the learner to read independently. Emphasise letter sounds at first and not letter names. (Learn letter names in the first instance by chanting the alphabet or singing an alphabet song.) Do not teach an initial sight vocabulary where learners are expected to memorise words as whole shapes. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Reading Comprehension Difficulties Handout for Students

Reading Comprehension Difficulties Definition: Reading comprehension is a process in which knowledge of language, knowledge of the world, and knowledge of a topic interact to make complex meaning. It involves decoding, word association, context association, summary, analogy, integration, and critique. The Symptoms: Students who have difficulty with reading comprehension may have trouble identifying and understanding important ideas in reading passages, may have trouble with basic reading skills such as word recognition, may not remember what they’ve read, and may frequently avoid reading due to frustration. How to improve your reading comprehension: It is important to note that this is not just an English issue—all school subjects require reading comprehension. The following techniques can help to improve your comprehension: Take a look at subheadings and any editor’s introduction before you begin reading so that you can predict what the reading will be about. Ask yourself what you know about a subject before you begin reading to activate prior knowledge. Ask questions about the text as you read—this engages your brain. Take notes as you read, either in the book or on separate paper: make note of questions you may have, interesting ideas, and important concepts, anything that strikes your fancy. This engages your brain as you read and gives you something to look back on so that you remember what to discuss with your instructor and/or classmates or possibly use in your work for the class. Make note of how texts in the subject area are structured you know how and where to look for different types of information. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

Effective Vocabulary Instruction by Joan Sedita

Published in “Insights on Learning Disabilities” 2(1) 33-45, 2005 Effective Vocabulary Instruction By Joan Sedita Why is vocabulary instruction important? Vocabulary is one of five core components of reading instruction that are essential to successfully teach children how to read. These core components include phonemic awareness, phonics and word study, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension (National Reading Panel, 2000). Vocabulary knowledge is important because it encompasses all the words we must know to access our background knowledge, express our ideas and communicate effectively, and learn about new concepts. “Vocabulary is the glue that holds stories, ideas and content together… making comprehension accessible for children.” (Rupley, Logan & Nichols, 1998/99). Students’ word knowledge is linked strongly to academic success because students who have large vocabularies can understand new ideas and concepts more quickly than students with limited vocabularies. The high correlation in the research literature of word knowledge with reading comprehension indicates that if students do not adequately and steadily grow their vocabulary knowledge, reading comprehension will be affected (Chall & Jacobs, 2003). There is a tremendous need for more vocabulary instruction at all grade levels by all teachers. The number of words that students need to learn is exceedingly large; on average students should add 2,000 to 3,000 new words a year to their reading vocabularies (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2002). For some categories of students, there are significant obstacles to developing sufficient vocabulary to be successful in school: • Students with limited or no knowledge of English. Literate English (English used in textbooks and printed material) is different from spoken or conversational English. -

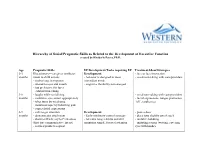

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple,