Free Full Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working with Students on the Autism Spectrum

Supporting students on the autism spectrum student mentor guidelines By Catriona Mowat, Anna Cooper and Lee Gilson Supporting students on the autism spectrum All rights reserved. No part of this book can be reproduced, stored in a retrievable system or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other wise without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published by The National Autistic Society 2011 Printed by RAP Spiderweb © The National Autistic Society 2011 Chapters Introduction 3 1. Understanding the autism spectrum 4-9 2. Your role as a student mentor 10-15 3. Getting started 16-23 4. Supporting a student with Asperger syndrome to… 24-29 5. Useful resources 30-33 6. Further reading 34 7. Glossary of terms 35 1 2 Introduction These guidelines were initially prepared as a resource for newly appointed student mentors supporting students with autism and Asperger syndrome at the University of Strathclyde. This guide has been rewritten as a useful resource for any university employing and training its own student mentors, or considering doing so. Readers may reproduce the guidelines, or relevant sections of the guidelines, as long as they acknowledge the source. This new version was made possible by a grant from the Scottish Funding Council in 2009, which has supported not only this publication, but also a research project (led by Charlene Tait of the National Centre for Autism Studies, University of Strathclyde) into transition and retention for students on the autism spectrum, and the delivery of a series of workshops on this topic (jointly delivered by the University of Strathclyde and The National Autistic Society Scotland). -

Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the Key Concept to Its Definition by Writing the Letter in the Correct Blank

AP HANDOUT 2A Alphabetic Principle, Word Study, and Spelling Definitions Match the key concept to its definition by writing the letter in the correct blank. Set A 1. ______ decoding A. Understanding that the sequence of letters in written words represents the sequence of sounds (or phonemes) in spoken words 2. ______common sound B. Sound that a letter most frequently makes in a word 3. ______decodable texts C. Vowels and certain consonant sounds that can be prolonged during pronunciation and are easier to say without being distorted 4. ______ encoding D. Engaging and coherent texts in which most of the words are comprised of an accumulating sequence of letter-sound correspondences being taught 5. ______ alphabetic E. Process of converting printed words into their spoken principle forms by using knowledge of letter-sound relationships and word structure 6. ______ continuous F. Process of converting spoken words into their written sounds forms (spelling) SET B 7. ______ sounding out G. Words in which some or all of the letters do not represent their most common sounds 8. ______ letter H. Groups of consecutive letters that represent a particular recognition sound(s) in words 9. ______ irregular words I. Ability to distinguish and name each letter of the alphabet, sequence the letters, and distinguish and produce both upper and lowercase letters 10. ______ regular words J. Relationships between common sounds of letters or letter combinations in written words 11. ______ stop sounds K. Words in which the letters make their most common sound 12. ______ letter-sound L. Process of saying each sound that represents a letter(s) in correspondences a word and blending them together to read it 13. -

Autism Entangled – Controversies Over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture

Autism Entangled – Controversies over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture Toby Atkinson BA, MA This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Lancaster University February 2021 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Furthermore, I declare that the word count of this thesis, 76940 words, does not exceed the permitted maximum. Toby Atkinson February 2021 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank my supervisors Hannah Morgan, Vicky Singleton, and Adrian Mackenzie for the invaluable support they offered throughout the writing of this thesis. I am grateful as well to Celia Roberts and Debra Ferreday for reading earlier drafts of material featured in several chapters. The research was made possible by financial support from Lancaster University and the Economic and Social Research Council. I also want to thank the countless friends, colleagues, and family members who have supported me during the research process over the last four years. 3 Contents DECLARATION ......................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. 9 PART ONE: ........................................................................................ -

The End of Illiteracy?

The End of Illiteracy? The Holy Grail of Clackmannanshire TOM BURKARD CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 1999 THE AUTHOR Tom Burkard is the Secretary of the Promethean Trust and has published several articles on how children learn to read. He contributed to the 1997 Daily Telegraph Schools Guide, and is a member of the NASUWT. His main academic interest is the interface between reading theory and classroom practice. His own remedial programme, recently featured in the Dyslexia Review, achieved outstanding results at Costessey High School in Norwich. His last Centre for Policy Study pamphlet, Reading Fever: Why phonics must come first (written with Martin Turner in 1996) proved instrumental in determining important issues in the National Curriculum for teacher training colleges. Acknowledgements Support towards research for this Study was given by the Institute for Policy Research. The Centre for Policy Studies never expresses a corporate view in any of its publications. Contributions are chosen for their independence of thought and cogency of argument. ISBN No. 1 897969 87 2 Centre for Policy Studies, March 1999 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 - 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. A brief history of the ‘reading wars’ 4 3. A comparison of analytic and synthetic phonics 9 4. Problems with the National Literacy Strategy 12 5. The success of synthetic phonics 17 6. Introducing synthetic phonics into the classroom 20 7. Recommendations 22 Appendix A: Problems with SATs 25 Appendix B: A summary of recent research on analytic phonics 27 Appendix C: Research on the effectiveness of synthetic phonics 32 SUMMARY The Government’s recognition of the gravity of the problem of illiteracy in Britain is welcome. -

Girls on the Autism Spectrum

GIRLS ON THE AUTISM SPECTRUM Girls are typically diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders at a later age than boys and may be less likely to be diagnosed at an early age. They may present as shy or dependent on others rather than disruptive like boys. They are less likely to behave aggressively and tend to be passive or withdrawn. Girls can appear to be socially competent as they copy other girls’ behaviours and are often taken under the wing of other nurturing friends. The need to fit in is more important to girls than boys, so they will find ways to disguise their difficulties. Like boys, girls can have obsessive special interests, but they are more likely to be typical female topics such as horses, pop stars or TV programmes/celebrities, and the depth and intensity of them will be less noticeable as unusual at first. Girls are more likely to respond to non-verbal communication such as gestures, pointing or gaze-following as they tend to be more focused and less prone to distraction than boys. Anxiety and depression are often worse in girls than boys especially as their difference becomes more noticeable as they approach adolescence. This is when they may struggle with social chat and appropriate small-talk, or the complex world of young girls’ friendships and being part of the in-crowd. There are books available that help support the learning of social skills aimed at both girls and boys such as The Asperkid’s Secret Book of Social Rules, by Jennifer Cook O’Toole and Asperger’s Rules: How to make sense of school and friends, by Blythe Grossberg. -

Autism & Faith Resources

AUTISM & FAITH RESOURCES BOOKS: Autism and Spirituality: Psyche, Self, and Spirit in People on the Autism Spectrum Olga Bogdashina The author argues persuasively that the spiritual development of those on the autism spectrum is in fact way ahead of that of their neurotypical peers. She describes differences in sensory perceptual, cognitive and linguistic development that make spiritual and religious experiences come more easily to those on the autism spectrum, and presents a coherent framework for understanding the routes of spiritual development and spiritual intelligence of giftedness within this group. Using research evidence and many real examples to illustrate her hypotheses, she suggests practical ways of supporting the spiritual needs of people on the autism spectrum and their families. Autism and Alleluias Kathleen Deyer Bolduc Almost everyone knows a family that has been affected by autism. What is the role that faith plays in helping families cope? In this series of slice-of-life vignettes, God's grace glimmers through as Joel, an intellectually challenged young adult with autism, teaches those who love him that life requires a childlike faith, humility, trust, and forgiveness. A Place Called Acceptance: Ministry With Families of Children With Disabilities Kathleen Deyer Bolduc The book describes how to welcome and minister to families of children with disabilities. The author discusses theology and disability, the grief process some parents experience, and the impact of disabilities on family systems. Including People with Disabilities in Faith Communities: A Guide for Service Providers, Families & Congregations Eric Carter This book addresses how faith communities, service providers, and families can work together to support the full participation of individuals with disabilities in the faith community of their choice. -

Autism Terminology Guidelines

The language we use to talk about autism is important. A paper published in our journal (Kenny, Hattersley, Molins, Buckley, Povey & Pellicano, 2016) reported the results of a survey of UK stakeholders connected to autism, to enquire about preferences regarding the use of language. Based on the survey results, we have created guidelines on terms which are most acceptable to stakeholders in writing about autism. Whilst these guidelines are flexible, we would like researchers to be sensitive to the preferences expressed to us by the UK autism community. Preferred language The survey highlighted that there is no one preferred way to talk about autism, and researchers must be sensitive to the differing perspectives on this issue. Amongst autistic adults, the term ‘autistic person/people’ was the most commonly preferred term. The most preferred term amongst all stakeholders, on average, was ‘people on the autism spectrum’. Non-preferred language: 1. Suffers from OR is a victim of autism. Consider using the following terms instead: o is autistic o is on the autism spectrum o has autism / an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) / an autism spectrum condition (ASC) (Note: The term ASD is used by many people but some prefer the term 'autism spectrum condition' or 'on the autism spectrum' because it avoids the negative connotations of 'disability' or 'disorder'.) 2. Kanner’s autism 3. Referring to autism as a disease / illness. Consider using the following instead: o autism is a disability o autism is a condition 4. Retarded / mentally handicapped / backward. These terms are considered derogatory and offensive by members of the autism community and we would advise that they not be used. -

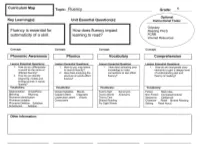

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

Alphabetic Principle

Alphabetic Principle What is it? The alphabetic principle refers to the understanding that there are predictable and consistent relations between written letters and spoken sounds – the combination of letter knowledge and awareness. The 26 letters are the “key” to the English language. They have names, shapes, sounds, and go together to make words. Why is it important? Children's knowledge of letter names, shapes and sounds is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters. As this becomes internalized we will see writing and reading skills grow. Considerations: (what to think about?) • Be intentional with the purpose and clear with the expectations. “We are going to be learning about the letters of the alphabet. There are 26 letters (use the abc line to count together slowly while you touch them). You all have some of them in your names (check that out with their name cards). Letters have sounds and go together to make words. Your name is a word….” How cool is that!!” Make it interesting and meaningful. Revisit the learning often … “What letters do you know really well? Which ones are still tricky?” Kids can answer this! • Have 2 alphabet strips - one high to teach from and one low for students to access (have a special abc pointer to reach the high one when you teach from it). Have them run in one long line. • Be very explicit when talking about the alphabet and clear when enunciating. -

Connections Between Sensory Sensitivities in Autism

PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal Volume 13 Issue 1 Underrepresented Content: Original Article 11 Contributions in Undergraduate Research 2019 Connections Between Sensory Sensitivities in Autism; the Importance of Sensory Friendly Environments for Accessibility and Increased Quality of Life for the Neurodivergent Autistic Minority. Heidi Morgan Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcnair Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Morgan, Heidi (2019) "Connections Between Sensory Sensitivities in Autism; the Importance of Sensory Friendly Environments for Accessibility and Increased Quality of Life for the Neurodivergent Autistic Minority.," PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 1, Article 11. https://doi.org/10.15760/mcnair.2019.13.1.11 This open access Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team. Portland State University McNair Research Journal 2019 Connections Between Sensory Sensitivities in Autism; the Importance of Sensory Friendly Environments for Accessibility and Increased Quality of Life for the Neurodivergent Autistic Minority. by Heidi Morgan Faculty Mentor: Miranda Cunningham Citation: Morgan H. (2019). Connections between sensory sensitivities in autism; the importance of sensory friendly environments for accessibility and increased quality of life for the neurodivergent autistic minority. Portland State University McNair Scholars Online Journal, Vol. 0 Connections Between Sensory Sensitivities in Autism; the Importance of Sensory Friendly Environments for Accessibility and Increased Quality of Life for the Neurodivergent Autistic Minority. -

Child-Centered Play Therapy and Young Children with Autism Katherine Elizabeth Carrizales

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-1-2015 Transcendence through Play: Child-Centered Play Therapy and Young Children with Autism Katherine Elizabeth Carrizales Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Carrizales, Katherine Elizabeth, "Transcendence through Play: Child-Centered Play Therapy and Young Children with Autism" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 13. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2015 KATHERINE ELIZABETH CARRIZALES ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School TRANSCENDENCE THROUGH PLAY: CHILD-CENTERED PLAY THERAPY AND YOUNG CHILDREN WITH AUTISM A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Katherine Elizabeth Carrizales College of Education and Behavioral Sciences Department of School Psychology May 2015 This Dissertation by: Katherine Elizabeth Carrizales Entitled: Transcendence Through Play: Child-Centered Play Therapy and Young Children with Autism has been approved as meeting the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in College of Education and Behavioral Sciences in Department of School Psychology -

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research The alphabetic principle is composed of two parts: • Alphabetic Understanding: Words are composed of letters that represent sounds. • Phonological Recoding: Using systematic relationships between letters and phonemes (letter-sound correspondence) to retrieve the pronunciation of an unknown printed string or to spell words. Phonological recoding consists of: o Regular Word Reading o Irregular Word Reading o Advanced Word Analysis Regular Word Reading A regular word is a word in which all the letters represent their most common sounds. Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded). Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1997). Beginning decoding ("phonological recoding") is the ability to: • read from left to right, simple, unfamiliar regular words. • generate the sounds for all letters. • blend sounds into recognizable words. Beginning spelling is the ability to: • translate speech to print using phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter-sounds. Progression of Regular Word Reading Skills Sight Word Sounding Saying the Reading Automatic Out Whole Word (sounding out Word (saying (saying each the word in your Reading each individual sound head, if (reading the individual and pronouncing necessary, and word without sound out the whole word) saying the sounding it