Khlevniukmaster.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Communism and Bolshevik Ideals" Is Devoted to a Case I N Point: the Dispute Over the Motivation of War Communism (The Name Given T O

TITLE : WAR COMMUNISM AND BOLSHEVIK IDEAL S AUTHOR : LARS T . LIH THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEA N RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION : ' CONTRACTOR : Wellesley Colleg e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Lars T. Li h COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 807-1 9 DATE : January 25, 199 4 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded b y Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within th e Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, o r make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without th e written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom o f information Act 5 U.S. C. 552, or other applicable law. The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (th e Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983) . The analysis and interpretations contained in th e report are those of the author. NCSEER NOTE This interpretive analysis of War Communism (1918-1921) may be of interest to those wh o anticipate further decline in the Russian economy and contemplate the possible purposes an d policies of a more authoritarian regime . -

Course Handbook

SL12 Page 1 of 29 UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE DEPARTMENT OF SLAVONIC STUDIES PAPER SL12: SOCIALIST RUSSIA 1917-1991 HANDBOOK Daria Mattingly [email protected] SL12 Page 2 of 29 INTRODUCTION COURSE AIMS The course is designed to provide you with a thorough grounding in and advanced understanding of Russia’s social, political and economic history in the period under review and to prepare you for the exam, all the while fostering in you deep interest in Soviet history. BEFORE THE COURSE BEGINS Familiarise yourself with the general progression of Soviet history by reading through one or more of the following: Applebaum, A. Red Famine. Stalin's War on Ukraine (2017) Figes, Orlando Revolutionary Russia, 1891-1991 (2014) Hobsbawm, E. J. The Age of Extremes 1914-1991 (1994) Kenez, Peter A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End (2006) Lovell, Stephen The Soviet Union: A Very Short Introduction (2009) Suny, Ronald Grigor The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States (2010) Briefing meeting: There’ll be a meeting on the Wednesday before the first teaching day of Michaelmas. Check with the departmental secretary for time and venue. It’s essential that you attend and bring this handbook with you. COURSE STRUCTURE The course comprises four elements: lectures, seminars, supervisions and reading. Lectures: you’ll have sixteen lectures, eight in Michaelmas and eight in Lent. The lectures provide an introduction to and overview of the course, but no more. It’s important to understand that the lectures alone won’t enable you to cover the course, nor will they by themselves prepare you for the exam. -

A Chronology Ofv. I. Lenin's Life (1870-1924)

A Chronology ofV. I. Lenin's Life (1870-1924) 1870 April: V. I. Lenin (born Vladimir Illich Ulyanov) is born in 1870 in the town of Simbirsk on the Volga River 1887 June: Lenin graduates from gymnasium (high school) 1887 May: Lenin's brother Alexander is executed 1887 August: Lenin enters the University of Kazan 1887 December: Lenin is arrested for participating in student protests 1887 December: Lenin is expelled from the University and exiled to the village of Kokushkino near Kazan' for one year 1891 November: Lenin graduates from the University of St. Petersburg 1893 Autumn: Lenin joins a Marxist circle in St. Petersburg 1894 Nicholas II becomes tsar 1895 December: Lenin is arrested and spends 14 months in prison. 1897 February: Lenin is sentenced to three years exile in Eastern Siberia 1898 July: Lenin marries Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaia 1898- 1900 In exile, Lenin writes The Development of Capitalism in Russia 1900 July: On returning from exile, Lenin goes abroad to Switzerland and other countries 1901 Lenin, who has been known until this point as Ulyanov, adopts the name N. Lenin 1901- 1902 Lenin writes What Is to Be Done? and edits Iskra (The Spark) 1903 July-August: Lenin attends the Second Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers' Party and helps to split the party into factions: Bolsheviks and Mensheviks 1904 February: Beginning of Russo-Japanese War 162 CHRONOLOGY 163 1904 December: Surrender of Port Arthur to Japanese 1905 january: The "Bloody Sunday" massacre; The First Russian Rev olution begins 1905 june-july. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Conspiracy of Peace: the Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956

The London School of Economics and Political Science Conspiracy of Peace: The Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956 Vladimir Dobrenko A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 90,957 words. Statement of conjoint work I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by John Clifton of www.proofreading247.co.uk/ I have followed the Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition, for referencing. 2 Abstract This thesis deals with the Soviet Union’s Peace Campaign during the first decade of the Cold War as it sought to establish the Iron Curtain. The thesis focuses on the primary institutions engaged in the Peace Campaign: the World Peace Council and the Soviet Peace Committee. -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

State-Sponsored Violence in the Soviet Union: Skeletal Trauma and Burial Organization in a Post-World War Ii Lithuanian Sample

STATE-SPONSORED VIOLENCE IN THE SOVIET UNION: SKELETAL TRAUMA AND BURIAL ORGANIZATION IN A POST-WORLD WAR II LITHUANIAN SAMPLE By Catherine Elizabeth Bird A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Anthropology- Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT STATE-SPONSORED VIOLENCE IN THE SOVIET UNION: SKELETAL TRAUMA AND BURIAL ORGANIZATION IN A POST WORLD WAR II LITHUANIAN SAMPLE By Catherine Elizabeth Bird The Stalinist period represented one of the worst eras of human rights abuse in the Soviet Union. This dissertation investigates both the victims and perpetrators of violence in the Soviet Union during the Stalinist period through a site specific and regional evaluation of burial treatment and perimortem trauma. Specifically, it compares burial treatment and perimortem trauma in a sample (n = 155) of prisoners executed in the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (L.S.S.R.) by the Soviet security apparatus from 1944 to 1947, known as the Tuskulenai case. Skeletal and mortuary variables are compared both over time and between security personnel in the Tuskulenai case. However, the Tuskulenai case does not represent an isolated event. Numerous other sites of state-sponsored violence are well known. In order to understand the temporal and geographical distribution of Soviet violence, this study subsequently compares burial treatment and perimortem trauma observed in the Tuskulenai case to data published in site reports for three other cases of Soviet state-sponsored violence (Vinnytsia, Katyn, and Rainiai). This dissertation discusses state-sponsored violence in the Soviet Union in the context of social and political theory advocated by Max Weber and within a principal-agent framework. -

David Brandenberger

DAVID BRANDENBERGER University of Richmond [email protected] Department of History Tel. (804) 289-8667 28 Westhampton Way Fax: (804) 287-6875 Richmond, VA 23173 facultystaff.richmond.edu/~dbranden E D U C A T I O N Harvard University. Ph.D., Department of History, November 16, 1999. Dissertation advisors: Richard Pipes, Roman Szporluk, Loren Graham & Terry Martin. Harvard University. A. M., Department of History, June 8, 1995. Macalester College. B.A., magna cum laude, History, Soviet/E. European Studies, May 23, 1992. S P E C I A L I Z A T I O N Russo-Soviet history; European & East European history; nationalism & national identity formation; ideology; Marxism; propaganda. E M P L O Y M E N T Professor, Department of History, University of Richmond (2016-) Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Richmond (2010-2016). Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Richmond (2003-2010). Visiting Lecturer in Russian History, Amherst College (2004-2005). Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, Connecticut College (2001). Lecturer, Department of History, Yale University (2000-2001). Lecturer, Committee on Degrees in History & Literature, Harvard University (1999-2002). B O O K M A N U S C R I P T S 1. Stalin’s Usable Past: A Critical Edition of the 1937 Short History of the USSR (in preparation, 2020-) 2. The Leningrad Affair: The Purge of Stalin’s Would-Be Successors, co-authored with K. A. Boldovskii and N. Iu. Pivovarov (in preparation, 2016-). 3. The Purge-Era Politburo Diaries of G. I. Petrovskii, co-edited with N. Iu. -

The Downgrading of Stalin As Seen from the Free World

• Address by Honorable William P. Rogers, Deputy Attorney General of the United States, on the occasion of Bryant College 93rd Commencement, Providence, Rhode Island Friday, August 3, 1956-10 a.m. The Downgrading of Stalin As Seen from the Free World resident Jacobs, Members of the Graduating Class, Distin guished Guests: It is with a great deal of pleasure that I P have looked forward to this occasion which permits me to participate in the Nintey-third Annual Commencement Exercises of Bryant College. It is a privilege to be asked to appear on this rostrum where so many distinguished persons have stood before and to address this year's graduating class and their friends and relatives. I am both indebted and pleased for the signal honor you have conferred in bestowing on me your Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws. To have been selected as a member of the Honor ary Alumni of Bryant College is a recognition which I shall always prize and for which I am deeply grateful. You members of the graduating class are soon to become re sponsible working members of our free society. I thought that I would talk to you LOday about recent events in Russia which point up, by startling contrast, the meaning of that free society in which we are privileged to live. Our laws are not the directives of any man or any group of men. They are the moral code of a free people. In the free world laws go hand in hand with religion. Our laws express what our people regard as right and what they regard as wrong-and they apply with equal force to all of our people, regardless of their station in life. -

Harvard Historical Studies • 173

HARVARD HISTORICAL STUDIES • 173 Published under the auspices of the Department of History from the income of the Paul Revere Frothingham Bequest Robert Louis Stroock Fund Henry Warren Torrey Fund Brought to you by | provisional account Unauthenticated Download Date | 4/11/15 12:32 PM Brought to you by | provisional account Unauthenticated Download Date | 4/11/15 12:32 PM WILLIAM JAY RISCH The Ukrainian West Culture and the Fate of Empire in Soviet Lviv HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2011 Brought to you by | provisional account Unauthenticated Download Date | 4/11/15 12:32 PM Copyright © 2011 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Risch, William Jay. The Ukrainian West : culture and the fate of empire in Soviet Lviv / William Jay Risch. p. cm.—(Harvard historical studies ; 173) Includes bibliographical references and index. I S B N 9 7 8 - 0 - 6 7 4 - 0 5 0 0 1 - 3 ( a l k . p a p e r ) 1 . L ’ v i v ( U k r a i n e ) — H i s t o r y — 2 0 t h c e n t u r y . 2 . L ’ v i v ( U k r a i n e ) — P o l i t i c s a n d government— 20th century. 3. L’viv (Ukraine)— Social conditions— 20th century 4. Nationalism— Ukraine—L’viv—History—20th century. 5. Ethnicity— Ukraine—L’viv— History—20th century. -

Fbarry-PATEJ Development Cannot Be Viewed with Complacency

'he was an alternate in the* THE EVENING STAR. Washington, D. C. •• ruling Politburo and obviously A-3 Malenkov Gets a Stalin favorite. He was one of five (with Stalin, Molotov. Beria and Marshal Klementi Voroshilov) on the top direc- 1,800 j jritrjfr torate for World War n. Job Miles ¦ In charge of reconstruction after the war, Malenkov did the impossible. As a reward he climbed to full Politburo From Moscow membership along with Beria. in 1946. But LONDON, July 11 ambitious Andrei /MOSCOW*'\ Kiro* \ Zhdanov, long considered Sta- cow radio says none of the de- 1 J lin's heir apparent, was gun- posed Kremlin leaders is being j ning for him. At Stalin's or- persecuted. It made that dec- ders, Zhdanov was preparing an laration in announcing that extensive party purge. Zhdan- ov, conveniently for Malen- Georgi Malenjov ißSljt Is being hus- kov, did in September, 1948. li|B . n°s power jl,-' tled off to run a plant Malenkov moved in and purged 1.800 miles from Moscow and Zhdanov men. Prominent rzi i jjjß CHANEL |jgjj^|J|Bl the other ousted leaders are Communists went to oblivion getting other and death. unspecified jobs. UST Got Stalin's Mantle Wk jr|SK m The broadcast last night ./J By October, c 1952. and the iMm ®fk$t wlt #¦ $ also asserted that the appoint- 19th party congress it was clear ! o BoAhoth - A TV ¦ J^SLr ment of the former Premier as A Malenkov could succeed Stalin ¦¦ premier. Others, including manager hydroelectric as of the Khrushchev, hitched their station at Ust Kamenogorsk is * • Tashkent wagons to his star. -

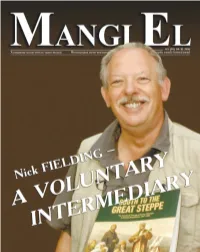

Тарих Толқынында В Потоке Истории in the Stream of History 1 Осы Санда in This Issue

ТАРИХ ТОЛҚЫНЫНДА В ПОТОКЕ ИСТОРИИ IN THE STREAM OF HISTORY 1 ОСЫ САНДА IN THIS ISSUE РЕДАКЦИЯ АЛҚАСЫ РЕДАКЦИОННАЯ КОЛЛЕГИЯ EDITORIAL BOARD РЕСПУБЛИКА КАЗАХСТАН И Ахмет ТОҚТАБАЕВ ЕВРАЗИЙСКОЕ ПРОСТРАНСТВО: Әбсаттар ДЕРБІСӘЛІ Бағлан МАЙЛЫБАЕВ Бауыржан БАЙТАНАЕВ Бүркітбай АЯҒАН РЕАЛИИ И ПЕРСПЕКТИВЫ Георгий КАН Ғаділбек ШАЛАХМЕТОВ Дихан ҚАМЗАБЕКҰЛЫ Ерлан СЫДЫҚОВ Жұлдызбек ӘБІЛХОЖИН Зиябек ҚАБЫЛДИНОВ Иманғали ТАСМАҒАМБЕТОВ Қаржаубай САРТҚОЖАҰЛЫ Марат ТАЖИН Махмұд ҚАСЫМБЕКОВ Мұхтар ҚҰЛ-МҰХАММЕД Нұрcан ӘЛІМБАЙ Уәлихан ҚАЛИЖАН Хангелді ӘБЖАНОВ Roxana SADVOKASSOVA. Ахмет ТОКТАБАЕВ Абсаттар ДЕРБИСАЛИ Баглан МАЙЛЫБАЕВ Буркитбай АЯГАН Nick FIELDING – Георгий КАН Гадильбек ШАЛАХМЕТОВ Дихан КАМЗАБЕКУЛЫ Ерлан СЫДЫКОВ A VOLUNTARY INTERMEDIARY Жулдызбек АБЫЛХОЖИН Зиябек КАБУЛЬДИНОВ Имангали ТАСМАГАМБЕТОВ Каржаубай САРТКОЖАУЛЫ Марат ТАЖИН Махмуд КАСЫМБЕКОВ Мухтар КУЛ-МУХАММЕД Нурсан АЛИМБАЙ Уалихан КАЛИЖАН Ханкельды АБЖАНОВ Akhmet TOKTABAYEV Absattar DERBISALI Baglan MAYLYBAYEV Bauirzhan BAYTANAYEV Burkitbay AYAGAN Дастан ЕЛЬДЕСОВ. Gadilbek SHALAKHMETOV Georgy KAN Dikhan KAMZABEKULY Yerlan SYDYKOV МАСТЕР, Zhuldyzbek ABYLKHOZHYN Ziyabek KABUL’DINOV Imangali TASMAGAMBETOV ОПЕРЕЖАЮЩИЙ ВРЕМЯ Karzhaubay SARTKOZHAULY Marat TAZHIN Mukhtar KUL-MUKHAMMED Makhmud KASSYMBEKOV Nursan ALIMBAY Ualikhan KALIZHAN Khangeldi ABZHANOV Басуға қол қойылды 10.10.2016 Подписано в печать 10.10.2016 Signed to print 10.10.2016 «Mangi El» халықаралық ғылыми-көпшілік тарихи журналы Международный научно-популярный исторический журнал «Mangi Еl» International popular scientific historical