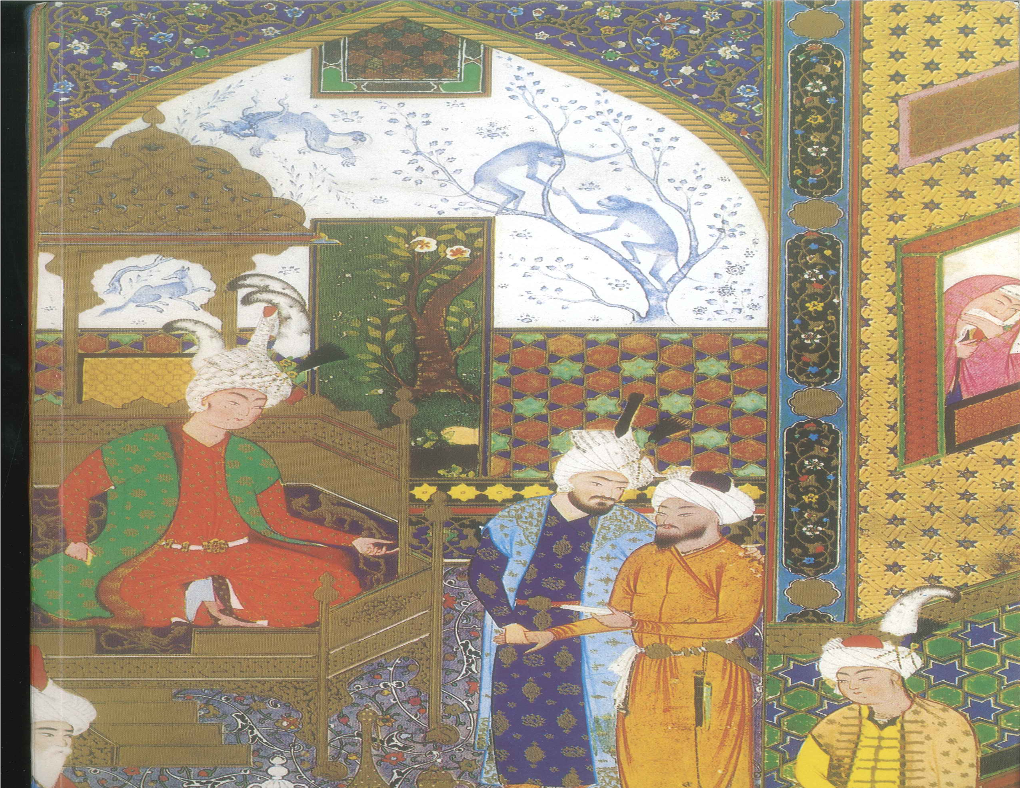

An Annotated Micro-History and Bibliography of the Houghton Shahnama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Persian 2704 SP15.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Persian 2704 Introduction to Persian Epic Instructor: Office Hours: Office: Email: No laptops, phones, or other mobile devices may be used in class. This course is about the Persian Book of Kings, Shahnameh, of the Persian poet Abulqasim Firdawsi. The Persian Book of Kings combines mythical themes and historical narratives of Iran into a mytho-historical narrative, which has served as a source of national and imperial consciousness over centuries. At the same time, it is considered one of the finest specimen of Classical Persian literature and one of the world's great epic tragedies. It has had an immense presence in the historical memory and political culture of various societies from Medieval to Modern, in Iran, India, Central Asia, and the Ottoman Empire. Yet a third aspect of this monumental piece of world literature is its presence in popular story telling tradition and mixing with folk tales. As such, a millennium after its composition, it remains fresh and rife in cultural circles. We will pursue all of those lines in this course, as a comprehensive introduction to the text and tradition. Specifically, we will discuss the following in detail: • The creation of Shahname in its historical context • The myth and the imperial image in the Shahname • Shahname as a cornerstone of “Iranian” identity. COURSE MATERIAL: • Shahname is available in English translation. -

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

ANNUAL REPORT for Fiscal Year 2018

ANNUAL REPORT for Fiscal Year 2018 MIRAMAR RANCH NORTH MAINTENANCE ASSESSMENT DISTRICT under the provisions of the San Diego Maintenance Assessment District Procedural Ordinance of the San Diego Municipal Code Prepared For City of San Diego, California Prepared By EFS Engineering, Inc. P.O. Box 22370 San Diego, CA 92192-2370 (858) 752-3490 June 2017 CITY OF SAN DIEGO Mayor Kevin Faulconer City Council Members Barbara Bry Mark Kersey District 1 District 5 (Council President Pro Tem) Lorie Zapf Chris Cate District 2 District 6 Chris Ward Scott Sherman District 3 District 7 Myrtle Cole David Alvarez District 4 (Council President) District 8 Georgette Gómez District 9 City Attorney Mara W. Elliott Chief Operating Officer Scott Chadwick City Clerk Elizabeth Maland Independent Budget Analyst Andrea Tevlin City Engineer James Nagelvoort Table of Contents Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2018 Miramar Ranch North Maintenance Assessment District Preamble........................................................................1 Executive Summary ......................................................2 Background ...................................................................3 District Boundary ..........................................................3 Project Description........................................................3 Separation of General and Special Benefits..................4 Cost Estimate.................................................................4 Annual Cost-Indexing .............................................5 Method of Apportionment.............................................5 -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

12 Magin.Pdf

Chicago Open 2014: A Redoubtable Coupling of Editors Packet by Moose Drool. Cool, Cool, Cool. (Stephen Liu, Sriram Pendyala, Jonathan Magin, Ryan Westbrook) Edited by Austin Brownlow, Andrew Hart, Ike Jose, Gautam & Gaurav Kandlikar, and Jacob Reed Tossups 1. In the book with this number from Silius Italicus’s Punica, Hannibal and Varro rouse their troops to fight the Battle of Cannae. Juvenal’s satire of this number concerns Naevolus, a male prostitute upset because his patron won’t give him money. Neifile sings the song “Io mi son giovinetta” at the end of this day of The Decameron, which is the only day besides the first in which the stories follow no prescribed theme. The line “no day shall erase you from the memory of time” is taken from this numbered book of The Aeneid, in which Nisus and Euryalus massacre sleeping Rutuli soldiers. Dante kicks the head of Bocca degli Abati in this circle of Hell, which is divided into regions including Antenora and Ptolomea. In a Petrarchan sonnet, this numbered line begins after the “volta,” or “turn.” Antaeus lowers Dante and Virgil into this circle of Hell, where Dante encounters Count Ugolino eating the head of Ruggieri. For 10 points, name this circle of Hell in which traitors are frozen in a lake of ice, the lowest circle of Dante’s Inferno. ANSWER: nine [or ninth; or nove if you have an Italian speaker] 2. An essay by William Hazlitt praises a fictional member of this profession named “Madame Pasta.” In the 18th century, Aaron Hill wrote many works to instruct members of this profession, who were lampooned in Charles Churchill’s satire The Rosciad. -

Mesaʼs 51St Annual Meeting

PRELIMINARY PROGRAM VER. 10-12-17 Jake McGuire Destination DC MESAʼs 51st Annual Meeting Washington DC November 18-21 We return to DC for MESA’s 51st annual meeting at the Washington Marriott Wardman Park Hotel where we have met every three years since 1999. The hotel is located in a lovely residential area near the National Zoo, but a nearby stop on the metro red line makes all parts of DC easily accessible. The program of 230+ sessions (see pages 12-51) spread over four days will offer a smorgasbord to whet the appetite of any Middle East studies aficionado. MESA’s affiliate groups meet mostly on Saturday, November 18 (see pages 10-11) and the first program session begins that day at 5:30pm. Panels run all day Sunday and Monday and end at 3pm on Tuesday. The book bazaar will be open Sunday and Monday from 9am to 6pm and on Tuesday from 8am to 12pm (see pages 8-9). MESAʼs ever-popular FilmFest (see the teaser on pages 6-7) begins screenings on Saturday morning and runs through Tuesday until around 2pm. The MESA Presidential Address & Awards will be held Sunday evening from 6pm to 7:30pm, and the MESA Members Meeting on Monday evening from 6pm to 8:00pm. As you will see, it’s business as usual, except of course for a new administration that is determined to ban nationals of six Muslim majority countries from traveling to the US, and MESA having joined a lawsuit against the ban that is making its way to the US Supreme Court in October. -

MCMPL NEWSLETTER Mary C

MCMPL NEWSLETTER Mary C. Moore Public Library Announcements & Events About Us Online newsletter: http://www.lacombelibrary.com/newsletter/ Hours Monthly feature display: Come hither and check out our display of fiction set in Medieval Monday-Thursday times! 10am-8pm Friday Join our Reading Challenge!: Explore new authors and titles, and grow as a reader. Pick up a 10am-5pm Reading Challenge bookmark at the library and read a book for each category listed. When you com- Saturday plete your challenge, fill in your info and drop off your bookmark at the library to be entered into the 10am-5pm draw for a fabulous prize, before September 28. You can also post book reviews on our facebook Sunday & Stat Holidays page or hand in a written review to be posted on the bulletin board in the library and featured in our Closed newsletter! For even more reading fun, do your challenge with your friends and family! Colouring Club for Adults: Wednesdays, September 7 & 21, drop-in 6-8pm in the library. Relax, Library Services unwind and enjoy quiet conversation while being creative! All materials provided. This program is free to attend! Adults only and older teens only, please. See our website for upcoming dates. Free Wi-Fi Film Club: For our September 27 meeting we are watching Still M ine, directed by Michael Free public computer access McGowan. Still Mine is an exquisitely crafted and deeply affecting love story about a couple in their twilight years. Based on true events and laced with wry humor, Still Mine tells the heartfelt tale of Printing Craig Morrison, who comes up against the system when he sets out to build a more suitable house for Faxing his ailing wife Irene. -

Abstracta Iranica, Volume 30 | 2010 « the Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 »

Abstracta Iranica Revue bibliographique pour le domaine irano-aryen Volume 30 | 2010 Comptes rendus des publications de 2007 « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The Journal of History, 90-1, 2007, pp. 62-91. [in Japanese] Akihiko Yamaguchi Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/abstractairanica/37797 DOI : 10.4000/abstractairanica.37797 ISSN : 1961-960X Éditeur : CNRS (UMR 7528 Mondes iraniens et indiens), Éditions de l’IFRI Édition imprimée Date de publication : 8 avril 2010 ISSN : 0240-8910 Référence électronique Akihiko Yamaguchi, « « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The Journal of History, 90-1, 2007, pp. 62-91. [in Japanese] », Abstracta Iranica [En ligne], Volume 30 | 2010, document 149, mis en ligne le 08 avril 2010, consulté le 27 septembre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/abstractairanica/37797 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/abstractairanica. 37797 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 27 septembre 2020. Tous droits réservés « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The ... 1 « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The Journal of History, 90-1, 2007, pp. 62-91. [in Japanese] Akihiko Yamaguchi 1 This is not only a useful overview on the formation process of the Ottoman-Iran border, which eventually offered today’s Iran with its western frontiers with Turkey and Iraq, but also a good case study on the introduction of the modern Western frontier concept into Islamic Middle East states. Showing that the demarcation process in the region goes back to the Ottoman-Safavid conflicts, the author argues that the second Erzurum treaty (1847), which finally established the Ottoman-Qajar boundary, adhered fundamentally to the preceding treaties concluded between successive Iranian dynasties and the Ottomans. -

From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Between the Cracks: From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 Amanda S. Wasielewski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3125 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BETWEEN THE CRACKS: FROM SQUATTING TO TACTICAL MEDIA ART IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1979–1993 by AMANDA WASIELEWSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 AMANDA WASIELEWSKI ALL Rights Reserved ii Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. Date David JoseLit Chair of Examining Committee Date RacheL Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marta Gutman Lev Manovich Marga van MecheLen THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski Advisor: David JoseLit In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was a battLeground. During this time, conflicts between squatters, property owners, and the police frequentLy escaLated into fulL-scaLe riots. -

Studies and Sources in Islamic Art and Architecture

STUDIES AND SOURCES IN ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE SUPPLEMENTS TO MUQARNAS Sponsored by the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. VOLUME IX PREFACING THE IMAGE THE WRITING OF ART HISTORY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY IRAN BY DAVID J. ROXBURGH BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roxburgh, David J. Prefacing the image : the writing of art history in sixteenth-century Iran / David J. Roxburgh. p. cm. — (Studies and sources in Islamic art and architecture. Supplements to Muqarnas, ISSN 0921 0326 ; v. 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9004113762 (alk. papier) 1. Art, Safavid—Historiography—Sources. 2. Art, Islamic—Iran– –Historiography—Sources. 3. Art criticism—Iran—History—Sources. I. Title. II. Series. N7283 .R69 2000 701’.18’095509024—dc21 00-062126 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Roxburgh, David J.: Prefacing the image : the writing of art history in sixteenth century Iran / by David J. Roxburgh. – Leiden; Boston; Köln : Brill, 2000 (Studies and sources in Islamic art and architectue; Vol 9) ISBN 90-04-11376-2 ISSN 0921-0326 ISBN 90 04 11376 2 © Copyright 2001 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA.