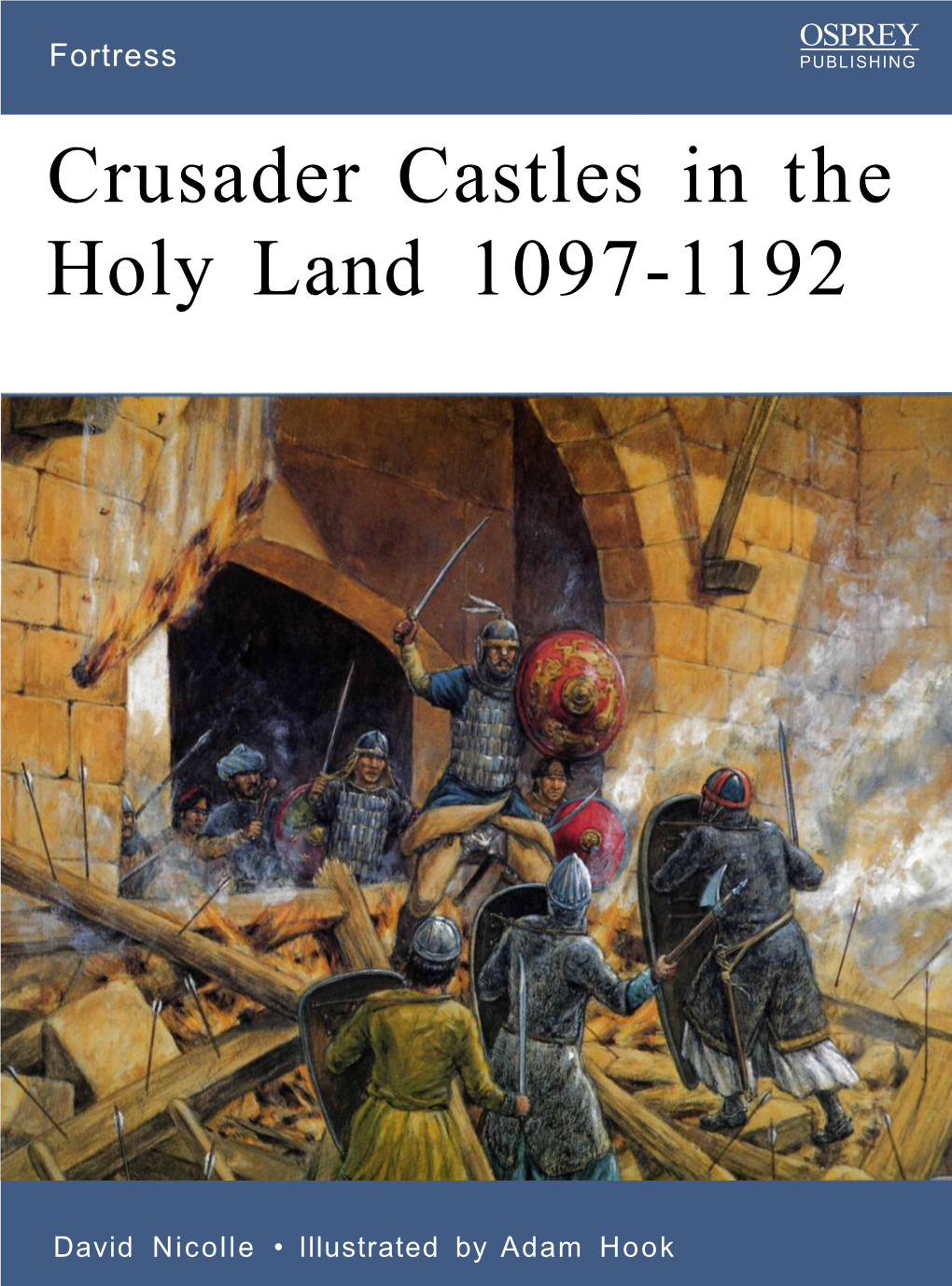

Crusader Castles in the Holy Land 1097-1192

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crusades -Medieval Social Formations

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN-II MODULE II-MEDIEVAL SOCIAL FORMATIONS TOPIC: CRUSADES Dr.Sr.Valsa M A ASSISTNT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY I BA ENGLISH COMPLEMENTARY PAPER CRUSADES The crusading movement was a series of military campaigns against the Muslims in the Middle east. It rooted from the act of pilgrimage supported by the church’s Gregorian reforms. Ecclesiastical reforms during the early medieval period caused drastic changes in the church governance and its relationship with the imperial sovereign They comprise a major chapter of medieval history . Extending over three centuries , they attracted every social class in central Europe , Kings and commoners, barons and bishops, knights and knaves- All participated in these expeditions to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. The rise and fall of the crusading movement was closely related to the fortunes of the high – medieval papal monarchy. Thus ,the Crusades can be seen as part of a chapter in papal and religious history. In addition , the Crusades opened the first chapter in the history of western colonialism. A long war series of wars between Christians and Muslims. Christian knights wanted to take the holy land (Jerusalem) and give it back to Christians. First Crusade (1095-1099) The First Crusade was a military campaign by Western European forces to recapture Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control. After about 2 years of traveling, the crusaders arrived in Jerusalem. After 2month siege, the city fell and the crusaders won Jerusalem back. This victory was brief, the Muslims soon retook Jerusalem under their control. Second crusades Muslim began retaking lands lost in First Crusade. -

The Crusades: 1

17/06/2020 THE CRUSADES: 1. AN ALTERNATE VIEW. U3A Stonnington. 17th JUNE 2020. (Albert Isaacs) INTRODUCTION: An 1850 painting by A MODERN PERSPECTIVE ON J. J. Dassy, depicting the Siege of Antioch, THE CRUSADES. during the First Crusade, 1095. 1 2 WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? According to the Oxford Dictionary, the first definition of the word “crusader” Today, most people only know of the Crusades fought in the Middle East (and is: a fighter in the medieval Crusades. The Oxford Dictionary’s second in Europe by Crusaders on their way to the Middle East). However, there definition is: a person who campaigns vigorously for political, social, or were Crusades prior to 1095, the time of the First Crusade in the Levant. religious change; a campaigner. By the 20th century, the second definition was the commonly accepted meaning, and many people using the word Any battle designed to convert so-called heathens to Christianity was usually didn’t give a thought to the word’s derivation in conflict. described as a Crusade and, as we’ll discuss later, there were many such fights in Europe prior to 1095. Even so, this presentation will mainly concentrate on In September 2001, just after 9/11 and on the eve of the Second Iraqi War, the Middle East. President George W. Bush declared: “a crusade against terrorism”. Most European encounters continued after the last battles in the Holy Land had commentators believe that President concluded. In fact, it could be argued that the Inquisitions, established by the Bush naively meant this within the Catholic Church in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, etc., were really continuations of context of the second definition of the the Crusades (). -

French Riviera Côte D'azur

10 20 FRENCH RIVIERA CÔTE D’AZUR SUGGESTIONS OF EXCURSIONS FROM THE PORT OF SUGGESTIONS D’EXCURSIONS AU DÉPART DU PORT DE CANNES EXCURSIONS FROM DEPARTURE EXCURSIONS AU DÉPART DE CANNES WE WELCOME YOU TO THE FRENCH RIVIERA Nous vous souhaitons la bienvenue sur la Côte d’Azur www.frenchriviera-tourism.com The Comité Régional du Tourisme (Regional Tourism Council) Riviera Côte d’Azur, has put together this document, following the specific request from individual cruise companies, presenting the different discovery itineraries of the towns and villages of the region pos- sible from the port, or directly the town of Cannes. To help you work out the time needed for each excursion, we have given an approximate time of each visit according the departure point. The time calculated takes into account the potential wait for public transport (train or bus), however, it does not include a lunch stop. We do advice that you chose an excursion that gives you ample time to enjoy the visit in complete serenity. If you wish to contact an established incoming tour company for your requirements, either a minibus company with a chauffeur or a large tour agency we invite you to consult the web site: www.frenchriviera-cb.com for a full list of the same. Or send us an e-mail with your specific requirements to: [email protected] Thank-you for your interest in our destination and we wish you a most enjoyable cruise. Monaco/Monte-Carlo Cap d’Ail Saint-Paul-de-Vence Villefranche-sur-Mer Nice Grasse Cagnes-sur-Mer Villeneuve-Loubet Mougins Biot Antibes Vallauris Cannes Saint-Tropez www.cotedazur-tourisme.com Le Comité Régional du Tourisme Riviera Côte d’Azur, à la demande d’excursionnistes croisiéristes individuels, a réalisé ce document qui recense des suggestions d’itinéraires de découverte de villes et villages au départ du port de croisières de Cannes. -

Red Sea Entanglement Initial Latin European Intellectual Development Regarding Nubia and Ethiopia During the Twelfth Century

DOI: 10.46586/er.11.2020.8826 Entangled Religions 11.5 (2020) License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 er.ceres.rub.de Red Sea Entanglement Initial Latin European Intellectual Development Regarding Nubia and Ethiopia during the Twelfth Century ADAM SIMMONS Nottingham Trent University, Great Britain ABSTRACT What happens to the ability to retrace networks when individual agents can- not be named and current archaeology is limited? In these circumstances, such networks cannot be traced, but, as this case study will show, they can be reconstructed and their effects can still be witnessed. This article will highlight how Latin European intellectual development regarding the Christian African kingdoms of Nubia and Ethiopia is due to multiple and far-reaching networks between Latin Europeans, Africans, and other Eastern groups, especially in the wider Red Sea region, despite scant direct evidence for the exis- tence of such extensive intellectual networks. Instead, the absence of direct evidence for Latin European engagement with the Red Sea needs to be situated within the wider devel- opment of Latin European understandings of Nubia and Ethiopia throughout the twelfth century as a result of interaction with varied peoples, not least with Africans themselves. The developing Latin European understanding of Nubia was a result of multiple and varied exchanges. KEYWORDS Crusades, Nubia, Ethiopia, Red Sea, twelfth century, intellectual history Introduction The establishment of the Crusader States at the turn of the twelfth century acted as a catalyst [1] for the development of Latin European knowledge of the wider Levant (e.g., Hamilton 2004). This knowledge was principally gained through direct and indirect interactions with various religious and ethnic groups, each of which acted as individual catalysts for a greater shared development of knowledge. -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

THE LOGISTICS of the FIRST CRUSADE 1095-1099 a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Wester

FEEDING VICTORY: THE LOGISTICS OF THE FIRST CRUSADE 1095-1099 A Thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By William Donald O’Dell, Jr. Director: Dr. Vicki Szabo Associate Professor of Ancient and Medieval History History Department Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History Dr. Robert Ferguson, History October, 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members and director for their assistance and encouragements. In particular, Dr. Vicki Szabo, without whose guidance and feedback this thesis would not exist, Dr. David Dorondo, whose guidance on the roles of logistics in cavalry warfare have helped shaped this thesis’ handling of such considerations and Dr. Robert Ferguson whose advice and recommendations for environmental historiography helped shaped my understanding on how such considerations influence every aspect of history, especially military logistics. I also offer my warmest regards and thanks to my parents, brothers, and extended family for their continued support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 -

The Crusades – from Christian, Jewish and Muslim Perspectives

1. What do the different accounts of the Crusades have in common? What commonalities, if any, do you detect between the religious ideas of the crusaders and those whom they attacked? What were the similarities and what were the differences in the experiences of the Jews in Rhineland cities and the Arabs in Jerusalem? Why do you think the response of the Jews was so different from the response of the Muslims? 2. What reasons does Pope Urban give for urging the Franks to take up arms and go to the Holy Land? What is the tone of his speech in presenting these reasons? Is this a rational appeal, or an emotional one? Or both? How important is religion in the appeal? What motivations other than religious ones does Urban give? Does his presentation of the reasons for this war conform to the requirements for a just war laid out by Augustine and Aquinas [it must (1) be defensive in nature; (2) violence must be proportionate, doing no more violence than it prevents; (3) aim must be the restoration of peace; and (4) be waged by a legal authority]? 3. Does what happened to the Jews in Germany and the Muslims in Jerusalem strike you as a logical outcome of Urban‘s appeal? 4. According to al-Athir‘s narrative, what is the cause of the Crusades to the Holy Land? How does his description of these causes and events compare with the Christian accounts of the launching of the First Crusade? How do you account for the different views of the same events? 5. -

Military Orders (Helen Nicholson) Alan V. Murray, Ed. the Crusades

Military Orders (Helen Nicholson) activities such as prayer and attending church services. Members were admitted in a formal religious ceremony. They wore a religious habit, but did not follow a fully enclosed lifestyle. Lay members Alan V. Murray, ed. The Crusades. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2006, pp. 825–829. predominated over priests in the early years, while the orders were still active in military affairs. The military order was a form of religious order first established in the first quarter of the twelfth The military orders were part of a religious trend of the late eleventh and early twelfth century toward century with the function of defending Christians, as well as observing the three monastic vows of wider participation in the religious life and more emphasis on action as against contemplation. The poverty, chastity, and obedience. The first military order was the Order of the Temple, formally Cistercian Order, founded at the end of the eleventh century, allowed laity from nonnoble families to established in the kingdom of Jerusalem in January 1120, while the Order of the Hospital (or Order of enter their order to perform manual tasks; orders of canons, founded in the late eleventh and early St. John of Jerusalem) began in the eleventh century as a hospice for pilgrims in Jerusalem and later twelfth centuries, could play an active role in society as priests working in the community, unlike on developed military responsibilities, perhaps as early as the mid-1120s. The Templars and traditional monks who lived enclosed lives in their monasteries. In the same way, the military orders Hospitallers became supranational religious orders, whose operations on the frontiers of Christendom did not follow a fully enclosed lifestyle, followed an active vocation, and were composed largely of laity: were supported by donations of land, money, and privileges from across Latin Christendom. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Jerusalem by Night…

Jerusalem by Night… www.feelJerusalem.com [email protected] Photo & edit: Ron Peled 2008 The roof of the Holy Sepulchre (Christ Tomb - the Golgotha) King David Citadel (The Tower of David ) The entrance to the Jaffa Gate Jerusalem's citadel, known as the ''Tower of David'', is a historical and archaeological site of world importance. Over the generations it has become both a landmark and a symbol of the city Inside the guardrooms of the citadel, the exhibition presents Jerusalem's history through a series of specially-designed models, illustrations, moving and static, and multi-media displays that relate the history in a chronological manner, focusing on the main events of each period This is essentially a medieval fortress, with later additions. Its towers and ramparts offer splendid views of that part of Jerusalem where Old and New merge. The site of the citadel has always been the weak point in the city's defenses, compelling its rulers throughout history to fortify the site Important Royal Discovery at the Museum. During the archaeological excavations of the Kishle in the grounds of the Tower of David Museum, remains from King Herod's palace were found World-breaking record of visitors to exhibition - Over 1.3 million visitors came to the Tower of David Museum in 2000 to see Chihuly's Glass exhibition making it the most popular temporary exhibition for the millennium year Mishkenot Sheananim - the first Jewish neighborhood outside the Old City walls Mishkenot Sheananim The Basilica of the Agony at Gethsemane (Church of All Nations) – Mount of Olives The Temple Mount – Mosque of El Aqza (left) and the Dome of the Rock Mosque of Al - Aqsa - according to Islamic tradition, Mohammad arrived on the back of a winged horse named “el-Buraq” (“The Lightning”). -

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 1 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract The Latin principality of Antioch was founded during the First Crusade (1095-1099), and survived for 170 years until its destruction by the Mamluks in 1268. This thesis offers the first full assessment of the thirteenth century principality of Antioch since the publication of Claude Cahen’s La Syrie du nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche in 1940. It examines the Latin principality from its devastation by Saladin in 1188 until the fall of Antioch eighty years later, with a particular focus on its relationship with the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. This thesis shows how the fate of the two states was closely intertwined for much of this period. The failure of the principality to recover from the major territorial losses it suffered in 1188 can be partly explained by the threat posed by the Cilician Armenians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. -

Urban Warfare in 15Th-Century Castile

Urban warfare in 15th-century Castile Guerra urbana en el siglo XV castellano Ekaitz Etxeberria Gallastegi* Universidad del País Vasco Abstract Urban warfare evokes unequivocally contemporary images. However, the Mid- dle Ages frequently witnessed combats inside cities. These confrontations usu- ally arose in two contexts: factional struggles to achieve local power, and street fighting derived from an enemy army entering the city after a successful as- sault. The aim of this paper is to analyse urban warfare in 15th-century Castile, examining its tactics and common characteristics. Keywords Urban Warfare, Castile, 15th century, Tactics. Resumen El combate urbano remite a unos referentes inequívocamente contemporáneos. Sin embargo, la Edad Media también fue escenario de frecuentes combates en el interior de las ciudades. Estos enfrentamientos solían responder a dos realida- des: la lucha entre bandos locales enfrentados por el poder y el combate calle- jero que podía suceder a la expugnación de la muralla por un ejército atacante. * Correo electrónico: [email protected]. Departamento de Historia Medieval, Moderna y América. Facultad de Letras de la Universidad del País Vasco. This paper was written within the framework of the Ministry of Science & Innovation funded Research Project De la Lucha de Bandos a la hidalguía universal: transformaciones so- ciales, políticas e ideológicas en el País Vasco (siglos XIV y XV), (HAR2017-83980-P) and of the Basque Government’s Consolidated Reseach Group Sociedad, poder y cultura (siglos XIV-XVIII), (IT-896-16). http://www.journal-estrategica.com/ E-STRATÉGICA, 3, 2019 • ISSN 2530-9951, pp. 125-143 125 EKAITZ ETXEBERRIA GALLASTEGI El presente artículo pretende definir las formas que adoptó el combate urbano en los enfrentamientos que tuvieron este escenario en la Castilla del siglo XV, estableciendo sus pautas e intentando discernir las características comunes de esta forma de enfrentamiento.