Balaam in Text and Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Expositor

THE EXPOSITOR. BALAAM: AN EXPOSITION AND STUDY. III. The Conclusion. WE have now studied all the Scriptures which relate to Balaam, and if our study has added but few new features to his character, it has served, I hope, to bring out his features more clearly, to cast higher lights and deeper shadows upon them, and to define and enlarge our conceptions both of the good and of the evil qualities of the man. The problem of his character-how a good man could be so. bad and a great man so base-has not yet been solved ; we are as far per haps from its solution as ever : but something-much has been gained if only we have the terms of that problem more distinctly and fully before our minds. To reach the solution of it, in so far as we can reach it, we must fall back on the second method of inquiry which, at the outset, I proposed to employ. We must apply the comparative method to the history and character of Balaam ; we must place him beside other prophets as faulty and sinful as himself, and in whom the elements were as strangely mixed as they were in him : we must endeavour to classify him, and to read the problem of his life in the light of that of men of his own order and type. Yet that is by no means easy to do without putting him to a grave disadvantage. For the only prophets with whom We can compare him are the Hebrew prophets ; and ·Balaam JULY, 1883. -

Japheth and Balaam

Redemption 304: Further Study on Japheth and Balaam biblestudying.net Brian K. McPherson and Scott McPherson Copyright 2012 Melchizedek (Shem), Japheth, and Balaam Summary of Relevant Information from Genesis Regarding Melchizedek and Abraham This exploratory paper assumes the conclusions of section three of our “Priesthood and the Kinsman Redeemer” study which identifies Melchizedek as Noah’s son Shem. Melchizedek was priest of Jerusalem (Salem) and possibly of the region in general. Shem was granted dominion over all the Canaanites by Noah. Genesis 9:22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without. 23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness. 24 And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him. 25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. 26 And he said, Blessed be the LORD God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. Melchizedek is clearly presented as a king. And Abraham clearly pays tithes or tribute to this king after a victory in battle. Genesis 14:18 And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God. 19 And he blessed him, and said, Blessed be Abram of the most high God, possessor of heaven and earth: 20 And blessed be the most high God, which hath delivered thine enemies into thy hand. -

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik Subject Area: Torah (Prophets) Multi-unit lesson plan Target age: 5th – 8th grades, 9th – 12th grades Objectives: • To acquaint students with prophets they may be unfamiliar with. • To familiarize the students with the social and moral message of selected prophets by engaging their analytical minds and visual senses. • To have students reflect in various media on the message of each of these prophets. • To introduce the students to contemporary examples of individuals who seem to live in the spirit of the prophets and their teachings. Materials: Descriptions of various forms of poetry including haiku, cinquain, acrostic, and free verse. Poster board, paper, markers, crayons, pencils, erasers. Quotations from the specific prophet being studied. Students may choose to use any of the materials available to create their sketches and posters. Class 1 through 3: Introduction to the prophets. The prophet Jonah. Teacher briefly talks about the role of the prophets. (See What is a Prophet, below) Teacher asks the students to relate the story of Jonah. Teacher briefly discusses the historical and social background of the prophet. Teacher asks if they can think of any fictional characters named Jonah. Why is the son in Sleepless in Seattle named Jonah? Teacher briefly talks about different forms of poetry. (see Poetry Forms, below) Students are asked to write a poem (any format) about the prophet Jonah. Students then draw a sketch that illustrates the Jonah story. Students create a poster based on the sketch and incorporating the poem they have written. Classes 4 through 8: The prophet Micah. -

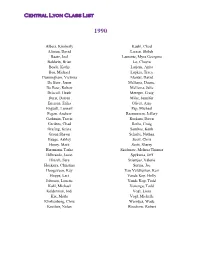

Central Lyon Class List

Central Lyon Class List 1990 Albers, Kimberly Kuehl, Chad Altman, David Larsen, Shiloh Baatz, Joel Laurente, Myra Georgina Baldwin, Brian Lo, Chayra Boyle, Kathy Lutjens, Anita Bus, Michael Lupkes, Tracy Cunningham, Victoria Mantal, David De Beor, Jason Mellema, Duane, De Boer, Robert Mellema, Julie Driscoll, Heath Metzger, Craig Durst, Darren Milar, Jennifer Enersen, Erika Oliver, Amy Enguall, Lennart Pap, Michael Fegan, Andrew Rasmussem, Jeffery Gathman, Travis Roskam, Dawn Gerdees, Chad Roths, Craig Grafing, Krista Sambos, Keith Groen Shawn Schulte, Nathan Hauge, Ashley Scott, Chris Henry, Mark Scott, Sherry Herrmann, Tasha Skidmore, Melissa Thinner Hilbrands, Jason Spyksma, Jeff Hinsch, Sara Stientjes, Valerie Hoekstra, Christina Surma, Joe Hoogeveen, Kay Van Veldhuizen, Keri Hoppe, Lari Vande Kop, Holly Johnson, Lonette Vande Kop, Todd Kahl, Michael Venenga, Todd Kelderman, Jodi Vogl, Lissa Kix, Marla Vogl, Michelle Klinkenborg, Chris Warntjes, Wade Kooiker, Nolan Woodrow, Robert Central Lyon Class List 1991 Andy, Anderson Mantle, Mark Lewis, Anderson Matson, Sherry Rachel, Baatz McDonald, Chad Lyle, Bauer Miller, Bobby Darcy, Berg Miller, Penny Paul, Berg Moser, Jason Shane, Boeve Mowry, Lisa Borman, Zachary Mulder, Daniel Breuker, Theodore Olsen, Lisa Christians, Amy Popkes, Wade De Yong, Jana Rath, Todd Delfs, Rodney Rau, Gary Ellsworth, Jason Roths, June Fegan, Carrie Schillings, Roth Gardner, Sara Schubert, Traci Gingras, Cindy Scott, Chuck Goette, Holly Solheim, Bill Grafing, Jennifer Steenblock, Amy Grafing, Robin Stettnichs, -

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title the Jews used in their Hebrew Old Testament for this book comes from the fifth word in the book in the Hebrew text, bemidbar: "in the wilderness." This is, of course, appropriate since the Israelites spent most of the time covered in the narrative of Numbers in the wilderness. The English title "Numbers" is a translation of the Greek title Arithmoi. The Septuagint translators chose this title because of the two censuses of the Israelites that Moses recorded at the beginning (chs. 1—4) and toward the end (ch. 26) of the book. These "numberings" of the people took place at the beginning and end of the wilderness wanderings and frame the contents of Numbers. DATE AND WRITER Moses wrote Numbers (cf. Num. 1:1; 33:2; Matt. 8:4; 19:7; Luke 24:44; John 1:45; et al.). He apparently wrote it late in his life, across the Jordan from the Promised Land, on the Plains of Moab.1 Moses evidently died close to 1406 B.C., since the Exodus happened about 1446 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1), the Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years (Num. 32:13), and he died shortly before they entered the Promised Land (Deut. 34:5). There are also a few passages that appear to have been added after Moses' time: 12:3; 21:14-15; and 32:34-42. However, it is impossible to say how much later. 1See the commentaries for fuller discussions of these subjects, e.g., Gordon J. -

Numbers 17-22

The Weekly Word August 31- September 6, 2020 September is here… Fall, my favorite season of the year, will soon be with us. Happy reading… Grace and Peace, Bill To hear the Bible read click this link… http://www.biblegateway.com/resources/audio/. Monday, August 31: Numbers 17- How God led me to his grace… The Lord uses a creative miracle to mark His leadership for Israel. Sometimes a show of force is necessary. Sometimes other measures can be used. This is one of the latter cases. Korah’s rebellion resulted in the death of 14,600 Israelites. The earth swallowed up Korah and his followers. After that a plague ravaged the camp. I can only imagine that the plague bred fear in the camp. With this as the background I see the brilliance of God choosing a creative miracle to set Aaron apart. This miracle I imagine inspired awe and wonder. I know it did in me. Having a staff sprout, bud and flower! Spectacular! The Lord has so many ways to display His power and glory. Different ways connect with different people. I know people who have experienced healings and this led them to the Lord. I know others who had dreams that brought them to the Lord. Others came to believe in the Lord through the witness of a friend and still others believe in the Lord because of the faithful living of their parents and families. Different means for different people all guided by the one Lord God almighty. I sat and remembered the many means God used to lead me to Jesus. -

A Star Was Born... About the Bifocal Reception History of Balaam

Scriptura 116 (2017:2): pp. 1-14 http://scriptura.journals.ac.za http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/116-2-1311 A STAR WAS BORN... ABOUT THE BIFOCAL RECEPTION HISTORY OF BALAAM Hans Ausloos University of the Free State Université catholique de Louvain – F.R.S.-FNRS Abstract Balaam counts among the most enigmatic characters within the Old Testament. Not everyone has the privilege of meeting an angel, and being addressed by a donkey. Moreover, the Biblical Balaam, as he is presented in Num. 22-24, has given rise to multiple interpretations: did the biblical authors want to narrate about a pagan diviner, who intended to curse the Israelites, but who was manipulated – against his will – by God in order to bless them, or was he rather considered to be a real prophet like Elijah or Isaiah? Anyway, that is at least the way he has been perceived by a segment of Christianity, considering him as one of the prophets who announced Jesus as the Christ? In the first section of this contribution, which I warmheartedly dedicate to Professor Hendrik ‘Bossie’ Bosman – we first met precisely twenty years ago during a research stay at Stellenbosch University in August 1997 – I will present the ambiguous presentation of Balaam that is given in Numbers 22-24 concisely. Secondly, I will concentrate on Balaam’s presentation in the other books of the Bible. Being aware of the fact that the reception history of the Pentateuch is one of Bossie’s fields of interest, in the last section I will show how the bifocal Biblical presentation of Balaam has left its traces on the reception of this personage in Christian arts. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

STUDY GUIDE The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Balak NUMBERS 22:2-25:9 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Parashat Balak Study Guide Themes Theme 1: The Seer Balaam—Have Vision Will Travel Theme 2: It’s a Slippery Slope—the Dangers of Foreign Women INTRODUCTION n Parashat Balak the Israelites are camped on the plains of Moab, ready Ito enter Canaan. In the midst of their final preparations to enter the land God promised to their ancestors, yet another obstacle emerges. Balak, king of Moab, grows concerned about the fierce reputation of the Israelites, which he observed in the Israelites’ encounter with the Amorites (Numbers 21:21–32). Balak’s subjects worry that the Israelites, due to their large numbers, will devour the resources of Moab. In response, Balak hires a well-known seer named Balaam to curse the Israelites, thus reflecting the widely held belief in the ancient world that putting a curse on someone was an effective means of subduing an enemy. The standoff between the powers of the God of Israel and those of a foreign seer proves to be no contest. Even Balaam’s talking female donkey, who represents the biblical ideal of wisdom, recognizes the efficacy of God’s power—unlike her human master, the professional seer. Although hired to curse the Israelites, Balaam ends up blessing them instead. In a series of four oracles, Balaam ultimately does the opposite of what Balak desires and establishes that the power of Israel’s God is greater than even the most skilled human seers. -

The Bible, King James Version, Book 5: Deuteronomy

The Bible, King James version, Book 5: Deuteronomy Project Gutenberg EBook The Bible, King James, Book 5: Deuteronomy Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **EBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These EBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers***** Title: The Bible, King James version, Book 5: Deuteronomy Release Date: May, 2005 [EBook #8005] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on June 7, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, THE BIBLE, KING JAMES, BOOK 5 *** This eBook was produced by David Widger [[email protected]] with the help of Derek Andrew's text from January 1992 and the work of Bryan Taylor in November 2002. Book 05 Deuteronomy 05:001:001 These be the words which Moses spake unto all Israel on this side Jordan in the wilderness, in the plain over against the Red sea, between Paran, and Tophel, and Laban, and Hazeroth, and Dizahab. -

The Zeal of Pinchas (Phinehas)

Kehilat Kol Simcha July 27, 2019 Gainesville, Florida Shabbat Teaching The Zeal of Pinchas (Phinehas) 10 Then Adonai spoke to Moses saying, 11 “Phinehas son of Eleazar son of Aaron the kohen has turned away My anger from Bnei-Yisrael because he was very zealous for Me among them, so that I did not put an end to Bnei-Yisrael in My zeal. 12 So now say: See, I am making with him a covenant of shalom! 13 It will be for him and his descendants a cove- nant of an everlasting priesthood—because he was zealous for his God and atoned for Bnei-Yisrael” (Nu. 25:10-13). It is advantageous to read/review the context of the beginning Parashat Pinchas when the Torah celebrates Pinchas’ zeal. Israel falls prey to the sin of immorality and idolatry. In last week’s Torah Reading (Balak) the gentile prophet Balaam was unable to curse Israel even though Moabite King Balak offered him a great reward. After blessing Israel in Numbers 24 Balaam and Balak depart from each other without Balaam getting any reward: “25 Then Balaam got up and went and returned to his own place, and Balak went on his way” (Numbers 24:25). That was not the end of Balaam’s influence and evil doings. Yeshua elucidates on the doctrine/teaching of Balaam to the Messianic Congregation at Pergamum: “14 But I have a few things against you. You have some there who hold to the teaching of Balaam, who was teaching Balak to put a stumbling block before Bnei-Yisrael, to eat food sacrificed to idols and to commit sexual immorality” (Rev. -

Matot-Masei – July 10, 2021

Stollen Moments – Matot-Masei – July 10, 2021 PARASHA SUMMARY FROM WWW. REFORMJUDAISM.ORG • Moses explains to the Israelites the laws concerning vows made by men and women. (30:2—17) • Israel wages war against the Midianites. (31:1—18) • The laws regarding the spoils of war are outlined. (31:19—54) • The tribes of Reuben and Gad are granted permission to stay on the east bank of the Jordan River. (32:1—42) • The itinerary of the Israelites through the wilderness from Egypt to Jordan is delineated. (33:1-49) • Moses tells Israel to remove the current inhabitants of the land that God will give them and to destroy their gods. (33:50-56) • The boundaries of the Land of Israel are defined, along with those of the Levitical cities and the cities of refuge. (34:1-35:15) • God makes a precise distinction between murder and manslaughter. (35:16-34) • The laws of inheritance as they apply to Israelite women are delineated. (36:1-13) Numbers Chapter 31 1 The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, 2 "Avenge the Israelite people on the Midianites; then you shall be gathered to your kin." 3 Moses spoke to the people, saying, "Let men be picked out from among you for a campaign, and let them fall upon Midian to wreak the Lord's vengeance on Midian. 4 You shall dispatch on the campaign a thousand from every one of the tribes of Israel." 5 So a thousand from each tribe were furnished from the divisions of Israel, twelve thousand picked for the campaign. -

The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 40 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2001 Joseph Smith's Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation Kent P. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Kent P. (2001) "Joseph Smith's Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 40 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackson: Joseph Smith's Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the B joseph smithssmithes Cooperscooperstowntown bible the historical context ofthe bible used in the joseph smith translation kent P jackson in october 1829 joseph smith and oliver cowdery obtained the bible that was later used in the preparation of joseph smiths new translation of the holy scriptures it was a quarto size king james translation published in 1828 by the H and E phinney company of Cooperscooperstowntown new york 1 the prophet and his scribe likely did not know that their new book would one day become an important artifact of the restoration and they proba- bly also never considered the position in