"Moses Wrote His Book and the Portion of Balaam" (Tb Bava Batra 14B)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Expositor

THE EXPOSITOR. BALAAM: AN EXPOSITION AND STUDY. III. The Conclusion. WE have now studied all the Scriptures which relate to Balaam, and if our study has added but few new features to his character, it has served, I hope, to bring out his features more clearly, to cast higher lights and deeper shadows upon them, and to define and enlarge our conceptions both of the good and of the evil qualities of the man. The problem of his character-how a good man could be so. bad and a great man so base-has not yet been solved ; we are as far per haps from its solution as ever : but something-much has been gained if only we have the terms of that problem more distinctly and fully before our minds. To reach the solution of it, in so far as we can reach it, we must fall back on the second method of inquiry which, at the outset, I proposed to employ. We must apply the comparative method to the history and character of Balaam ; we must place him beside other prophets as faulty and sinful as himself, and in whom the elements were as strangely mixed as they were in him : we must endeavour to classify him, and to read the problem of his life in the light of that of men of his own order and type. Yet that is by no means easy to do without putting him to a grave disadvantage. For the only prophets with whom We can compare him are the Hebrew prophets ; and ·Balaam JULY, 1883. -

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik Subject Area: Torah (Prophets) Multi-unit lesson plan Target age: 5th – 8th grades, 9th – 12th grades Objectives: • To acquaint students with prophets they may be unfamiliar with. • To familiarize the students with the social and moral message of selected prophets by engaging their analytical minds and visual senses. • To have students reflect in various media on the message of each of these prophets. • To introduce the students to contemporary examples of individuals who seem to live in the spirit of the prophets and their teachings. Materials: Descriptions of various forms of poetry including haiku, cinquain, acrostic, and free verse. Poster board, paper, markers, crayons, pencils, erasers. Quotations from the specific prophet being studied. Students may choose to use any of the materials available to create their sketches and posters. Class 1 through 3: Introduction to the prophets. The prophet Jonah. Teacher briefly talks about the role of the prophets. (See What is a Prophet, below) Teacher asks the students to relate the story of Jonah. Teacher briefly discusses the historical and social background of the prophet. Teacher asks if they can think of any fictional characters named Jonah. Why is the son in Sleepless in Seattle named Jonah? Teacher briefly talks about different forms of poetry. (see Poetry Forms, below) Students are asked to write a poem (any format) about the prophet Jonah. Students then draw a sketch that illustrates the Jonah story. Students create a poster based on the sketch and incorporating the poem they have written. Classes 4 through 8: The prophet Micah. -

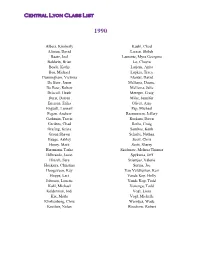

Central Lyon Class List

Central Lyon Class List 1990 Albers, Kimberly Kuehl, Chad Altman, David Larsen, Shiloh Baatz, Joel Laurente, Myra Georgina Baldwin, Brian Lo, Chayra Boyle, Kathy Lutjens, Anita Bus, Michael Lupkes, Tracy Cunningham, Victoria Mantal, David De Beor, Jason Mellema, Duane, De Boer, Robert Mellema, Julie Driscoll, Heath Metzger, Craig Durst, Darren Milar, Jennifer Enersen, Erika Oliver, Amy Enguall, Lennart Pap, Michael Fegan, Andrew Rasmussem, Jeffery Gathman, Travis Roskam, Dawn Gerdees, Chad Roths, Craig Grafing, Krista Sambos, Keith Groen Shawn Schulte, Nathan Hauge, Ashley Scott, Chris Henry, Mark Scott, Sherry Herrmann, Tasha Skidmore, Melissa Thinner Hilbrands, Jason Spyksma, Jeff Hinsch, Sara Stientjes, Valerie Hoekstra, Christina Surma, Joe Hoogeveen, Kay Van Veldhuizen, Keri Hoppe, Lari Vande Kop, Holly Johnson, Lonette Vande Kop, Todd Kahl, Michael Venenga, Todd Kelderman, Jodi Vogl, Lissa Kix, Marla Vogl, Michelle Klinkenborg, Chris Warntjes, Wade Kooiker, Nolan Woodrow, Robert Central Lyon Class List 1991 Andy, Anderson Mantle, Mark Lewis, Anderson Matson, Sherry Rachel, Baatz McDonald, Chad Lyle, Bauer Miller, Bobby Darcy, Berg Miller, Penny Paul, Berg Moser, Jason Shane, Boeve Mowry, Lisa Borman, Zachary Mulder, Daniel Breuker, Theodore Olsen, Lisa Christians, Amy Popkes, Wade De Yong, Jana Rath, Todd Delfs, Rodney Rau, Gary Ellsworth, Jason Roths, June Fegan, Carrie Schillings, Roth Gardner, Sara Schubert, Traci Gingras, Cindy Scott, Chuck Goette, Holly Solheim, Bill Grafing, Jennifer Steenblock, Amy Grafing, Robin Stettnichs, -

Manasseh: Reflections on Tribe, Territory and Text

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive MANASSEH: REFLECTIONS ON TRIBE, TERRITORY AND TEXT By Ellen Renee Lerner Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion August, 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Douglas A. Knight Professor Jack M. Sasson Professor Annalisa Azzoni Professor Herbert Marbury Professor Tom D. Dillehay Copyright © 2014 by Ellen Renee Lerner All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people I would like to thank for their role in helping me complete this project. First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee: Professor Douglas A. Knight, Professor Jack M. Sasson, Professor Annalisa Azzoni, Professor Herbert Marbury, and Professor Tom Dillehay. It has been a true privilege to work with them and I hope to one day emulate their erudition and the kind, generous manner in which they support their students. I would especially like to thank Douglas Knight for his mentorship, encouragement and humor throughout this dissertation and my time at Vanderbilt, and Annalisa Azzoni for her incredible, fabulous kindness and for being a sounding board for so many things. I have been lucky to have had a number of smart, thoughtful colleagues in Vanderbilt’s greater Graduate Dept. of Religion but I must give an extra special thanks to Linzie Treadway and Daniel Fisher -- two people whose friendship and wit means more to me than they know. -

Chukat Artscroll P.838 | Haftarah P.1187 Hertz P.652 | Haftarah P.664 Soncino P.898 | Haftarah P.911

13 July 2019 10 Tammuz 5779 Shabbat ends London 10.16pm Jerusalem 8.28pm Volume 31 No. 45 Chukat Artscroll p.838 | Haftarah p.1187 Hertz p.652 | Haftarah p.664 Soncino p.898 | Haftarah p.911 In loving memory of Yehuda ben Yaakov HaCohen “Speak to the Children of Israel, and they shall take to you a completely red cow, which is without blemish, and upon which a yoke has not come” (Bemidbar 19:2). 1 Sidrah Summary: Chukat 1st Aliya (Kohen) – Bemidbar 19:1-17 Kadesh through his land. Despite Moshe’s God tells Moshe and Aharon to teach the nation assurances that they will not take any of his the laws of the Red Heifer ( ). The resources, Edom refuses and comes out to unblemished animal, which hPaasr anhe vAedr uhmada h a yoke threaten the Israelites militarily. The Israelites upon it, is to be given to Elazar, Aharon’s son, who turn away. must slaughter it outside the camp. It is then to be 5th Aliya (Chamishi) – 20:22-21:9 burned by a different Kohen, who must also throw The nation travels from Kadesh to Mount Hor. some cedar wood, hyssop and crimson thread Upon God’s command, Moshe, Aharon and Elazar into the fire. Both he and Elazar will become ritually ascend Mount Hor. Elazar dons Aharon’s special impure ( ) through this preparatory process. (High Priest) garments, after which In contratasmt, ethe ashes of the Heifer, when mixed AKhohareonn G daiedso.l The nation mourns Aharon’s death with water, are used to purify someone who has for 30 days (see p.3 article). -

Balaam and Balak

Unit 7 • Session 3 Use Week of: Unit 7 • Session 3 Balaam and Balak BIBLE PASSAGE: Numbers 22–24 STORY POINT: God commanded Balaam to bless His people. KEY PASSAGE: Proverbs 3:5-6 BIG PICTURE QUESTION: What does it mean to sin? To sin is to think, speak, or behave in any way that goes against God and His commands. • Countdown • Review (4 min.) • Introduce the session (2 min.) • Key passage (5 min.) • Big picture question (1 min.) • Group game (5–10 min.) • Giant timeline (1 min.) • Sing and give offering (3–12 min.) • Tell the Bible story (10 min.) • Missions moment (6 min.) • Christ connection • Announcements (2 min.) • Group demonstration (5 min.) • Prayer (2 min.) • Additional idea Additional resources are available at gospelproject.com. For free training and session-by- session help, visit www.ministrygrid.com/web/thegospelproject. Kids Worship Guide 34 Unit 7 • Session 3 © 2018 LifeWay LEADER Bible Study God’s people, the Israelites, were in the wilderness. They had arrived at the promised land decades earlier, but the people had rebelled—refusing to trust God to give them the land. They believed it would be better to die in the wilderness than follow God (Num. 14:2), so God sent them into the wilderness for 40 years (vv. 28-29). In time, all of the adults died except for Joshua, Caleb, and Moses. The children grew up and more children were born. The Israelites disobeyed God time and again, but God still provided for them. He planned to keep His promise to give Israel the promised land. -

Deuteronomy 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Deuteronomy 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible was its first two words, 'elleh haddebarim, which translate into English as "these are the words" (1:1). Ancient Near Eastern suzerainty treaties began the same way.1 So the Jewish title gives a strong clue to the literary character of Deuteronomy. The English title comes from a Latinized form of the Septuagint (Greek) translation title. "Deuteronomy" means "second law" in Greek. We might suppose that this title arose from the idea that Deuteronomy records the law as Moses repeated it to the new generation of Israelites who were preparing to enter the land, but this is not the case. It came from a mistranslation of a phrase in 17:18. In that passage, God commanded Israel's kings to prepare "a copy of this law" for themselves. The Septuagint translators mistakenly rendered this phrase "this second [repeated] law." The Vulgate (Latin) translation, influenced by the Septuagint, translated the phrase "second law" as deuteronomium, from which "Deuteronomy" is a transliteration. The Book of Deuteronomy is, to some extent, however, a repetition to the new generation of the Law that God gave at Mt. Sinai. For example, about 50 percent of the "Book of the Covenant" (Exod. 20:23— 23:33) is paralleled in Deuteronomy.2 Thus God overruled the translators' error, and gave us a title for the book in English that is appropriate, in view of the contents of the book.3 1Meredith G. Kline, "Deuteronomy," in The Wycliffe Bible Commentary, p. -

The Story of Balaam

Primary Education www.GodsAcres.org Church of God Sunday School THE STORY OF BALAAM Numbers 21:21 — 24:25; 31:1-16 Deuteronomy 18:10; 23:4 As the people of honour" and to do whatever Balaam asked if he would Israel continued to trav- only come and curse Israel. Balaam's answer was, "If el toward Canaan, God Balak would give me his house full of silver and gold, gave them great victo- I cannot go beyond the word of the LORD my God, to ries over two mighty kings—Sihon (SAI-hon), king of do less or more." the Amorites (AM-uh-rights), and Og, king of Bashan That should have been the end of the story. How- (BAY-shuhn). Soon Israel came to the land of the Moa- ever, Balaam then asked the men to stay overnight to bites (MO-uh-bites). The people of Moab were afraid see what God would say. (Was he hoping that God of the Israelites, "because they were many." would change His mind?) That night God told Balaam, Balak (BAY-lak), the king of the Moabites, had a "If the men come to call thee, rise up, and go with plan. He sent messengers on a long journey to Pethor them; but yet the word which I shall say unto thee, that (peth-ORE), a distance of almost 400 miles. These shalt thou do." The next morning, Balaam got up, sad- messengers were to find a man by the name of Balaam dled his ass (donkey), and went with the Moabite men. -

Connection to Numbers 22:22-35 Balak Was King of the Moabites And

Numbers; Deuteronomy Sermon Series Supports Session 5: God Calls Sermon Title: “Blessing from Curses” Passage: Numbers 23–24 Connection to Numbers 22:22-35 Balak was king of the Moabites and feared what the Israelites might do to him and his kingdom. Balak hired Balaam to come and pronounce a curse upon the people of Israel. God would not allow Balaam to curse His people; instead, Balaam blessed Israel. Introduction/Opening God’s promises will come to pass. Nothing can stop God’s promises from being fulfilled. No amount of money, greed, or people can keep what God has promised from coming to pass. This is seen in the account of Balak and Balaam. King Balak of the Moabites has hired Balaam to curse the people of Israel. However, God did not allow Balaam to curse Israel, because He had promised to bless Israel. Outline 1. First Attempt at Cursing (Num. 23:7-12) a. Balaam was hired to curse Israel; however, the Lord met with Balaam and put a message in Balaam’s mouth (v. 5). b. Balaam delivered the message to Balak and was unable to curse Israel. Instead Balaam spoke of his inability to curse those whom God had not cursed (v. 8). Balak was upset that Balaam did not curse Israel (v. 11). 2. Second Attempt at Cursing (Num. 23:13-26) a. Balak took Balaam to a second location so that he could see the outskirts of Israel’s camp and asked him again to curse Israel (v. 13). b. The Lord met Balaam again and gave Balaam a message. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

STUDY GUIDE The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Balak NUMBERS 22:2-25:9 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Parashat Balak Study Guide Themes Theme 1: The Seer Balaam—Have Vision Will Travel Theme 2: It’s a Slippery Slope—the Dangers of Foreign Women INTRODUCTION n Parashat Balak the Israelites are camped on the plains of Moab, ready Ito enter Canaan. In the midst of their final preparations to enter the land God promised to their ancestors, yet another obstacle emerges. Balak, king of Moab, grows concerned about the fierce reputation of the Israelites, which he observed in the Israelites’ encounter with the Amorites (Numbers 21:21–32). Balak’s subjects worry that the Israelites, due to their large numbers, will devour the resources of Moab. In response, Balak hires a well-known seer named Balaam to curse the Israelites, thus reflecting the widely held belief in the ancient world that putting a curse on someone was an effective means of subduing an enemy. The standoff between the powers of the God of Israel and those of a foreign seer proves to be no contest. Even Balaam’s talking female donkey, who represents the biblical ideal of wisdom, recognizes the efficacy of God’s power—unlike her human master, the professional seer. Although hired to curse the Israelites, Balaam ends up blessing them instead. In a series of four oracles, Balaam ultimately does the opposite of what Balak desires and establishes that the power of Israel’s God is greater than even the most skilled human seers. -

Finding God in the Book of Moses Part 2

Finding God in The Book of Moses Part 2 Santa Barbara Community Church Summer Calendar 2007 Teaching Study Text Title Date 6/3 13 Leviticus 9:1— Unforgettable Fire: God’s Glory 10:11 6/10 14 Leviticus 16 The Day of Atonement: Grace Foreshadowed 6/17 15 Leviticus 18 A Third Culture: God and Purity 6/24 16 Leviticus 19 Leaving the Edges: God and Society 7/1 17 Numbers 11 Grumbling and Grace 7/8 18 Numbers 13-14 Surveillance and Rebellion: God and Faithfulness 7/15 19 Numbers 20:1— The Water and the Snake: God, 21:9 Discipline and Grace 7/22 20 Numbers 22-25 Balaam’s Funky Prophecy: A Promise of Messiah 7/29 21 Deuteronomy Obedience to a Jealous God 4:1-40 8/5 22 Deuteronomy Hearing God 4:44—6:25 8/12 23 Deuteronomy Circumcised Hearts: God’s Salvation 10:12—11:32 8/19 24 Deuteronomy The Problem of Idolatry 12—13 8/26 25 Deuteronomy The Choice is Yours 29-30 The text of this study was written and prepared by Reed Jolley. Thanks to, Erin Patterson, and Susi Lamoutte for proof reading the study. And thanks to Kat McLean (cover and studies 13, 15, 19, 21, 23, 25) and Andy Patterson (studies 14, 16, 17, 18, 20, 22, 24) for providing the illustrations. All Scripture citations unless otherwise noted are from the English Standard Version. May God bless Santa Barbara Community Church as we study his word! SOURCES/ABBREVIATIONS Brown Raymond Brown. The Message of Numbers, IVP, 2002 Childs Brevard Childs. -

The Zeal of Pinchas (Phinehas)

Kehilat Kol Simcha July 27, 2019 Gainesville, Florida Shabbat Teaching The Zeal of Pinchas (Phinehas) 10 Then Adonai spoke to Moses saying, 11 “Phinehas son of Eleazar son of Aaron the kohen has turned away My anger from Bnei-Yisrael because he was very zealous for Me among them, so that I did not put an end to Bnei-Yisrael in My zeal. 12 So now say: See, I am making with him a covenant of shalom! 13 It will be for him and his descendants a cove- nant of an everlasting priesthood—because he was zealous for his God and atoned for Bnei-Yisrael” (Nu. 25:10-13). It is advantageous to read/review the context of the beginning Parashat Pinchas when the Torah celebrates Pinchas’ zeal. Israel falls prey to the sin of immorality and idolatry. In last week’s Torah Reading (Balak) the gentile prophet Balaam was unable to curse Israel even though Moabite King Balak offered him a great reward. After blessing Israel in Numbers 24 Balaam and Balak depart from each other without Balaam getting any reward: “25 Then Balaam got up and went and returned to his own place, and Balak went on his way” (Numbers 24:25). That was not the end of Balaam’s influence and evil doings. Yeshua elucidates on the doctrine/teaching of Balaam to the Messianic Congregation at Pergamum: “14 But I have a few things against you. You have some there who hold to the teaching of Balaam, who was teaching Balak to put a stumbling block before Bnei-Yisrael, to eat food sacrificed to idols and to commit sexual immorality” (Rev.