The Expositor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Urging All of Us to Open Our Minds and Hearts So That We Can Know Beyond

CHAPTER 1 HOLISTIC READING We have left the land and embarked. We have burned our bridges behind us- indeed we have gone farther and destroyed the land behind us. Now, little ship, look out! Beside you is the ocean: to be sure, it does not always roar, and at times it lies spread out like silk and gold and reveries of graciousness. But hours will come when you realize that it is infinite and that there is nothing more awesome than infinity... Oh, the poor bird that felt free now strikes the walls of this cage! Woe, when you feel homesick for the land as if it had offered more freedom- and there is no longer any ―land.‖ - Nietzsche Each man‘s life represents a road toward himself, an attempt at such a road, the intimation of a path. No man has ever been entirely and completely himself. Yet each one strives to become that- one in an awkward, the other in a more intelligent way, each as best he can. Each man carries the vestiges of his birth- the slime and eggshells of his primeval past-… to the end of his days... Each represents a gamble on the part of nature in creation of the human. We all share the same origin, our mothers; all of us come in at the same door. But each of us- experiments of the depths- strives toward his own destiny. We can understand one another; but each is able to interpret himself alone. – Herman Hesse 1 In this chapter I suggest a new method of reading, which I call “holistic reading.” Building on the spiritual model of the Self offered by Jiddu Krishnamurti and the psychological model of “self” offered by Dr. -

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik Subject Area: Torah (Prophets) Multi-unit lesson plan Target age: 5th – 8th grades, 9th – 12th grades Objectives: • To acquaint students with prophets they may be unfamiliar with. • To familiarize the students with the social and moral message of selected prophets by engaging their analytical minds and visual senses. • To have students reflect in various media on the message of each of these prophets. • To introduce the students to contemporary examples of individuals who seem to live in the spirit of the prophets and their teachings. Materials: Descriptions of various forms of poetry including haiku, cinquain, acrostic, and free verse. Poster board, paper, markers, crayons, pencils, erasers. Quotations from the specific prophet being studied. Students may choose to use any of the materials available to create their sketches and posters. Class 1 through 3: Introduction to the prophets. The prophet Jonah. Teacher briefly talks about the role of the prophets. (See What is a Prophet, below) Teacher asks the students to relate the story of Jonah. Teacher briefly discusses the historical and social background of the prophet. Teacher asks if they can think of any fictional characters named Jonah. Why is the son in Sleepless in Seattle named Jonah? Teacher briefly talks about different forms of poetry. (see Poetry Forms, below) Students are asked to write a poem (any format) about the prophet Jonah. Students then draw a sketch that illustrates the Jonah story. Students create a poster based on the sketch and incorporating the poem they have written. Classes 4 through 8: The prophet Micah. -

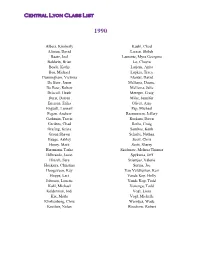

Central Lyon Class List

Central Lyon Class List 1990 Albers, Kimberly Kuehl, Chad Altman, David Larsen, Shiloh Baatz, Joel Laurente, Myra Georgina Baldwin, Brian Lo, Chayra Boyle, Kathy Lutjens, Anita Bus, Michael Lupkes, Tracy Cunningham, Victoria Mantal, David De Beor, Jason Mellema, Duane, De Boer, Robert Mellema, Julie Driscoll, Heath Metzger, Craig Durst, Darren Milar, Jennifer Enersen, Erika Oliver, Amy Enguall, Lennart Pap, Michael Fegan, Andrew Rasmussem, Jeffery Gathman, Travis Roskam, Dawn Gerdees, Chad Roths, Craig Grafing, Krista Sambos, Keith Groen Shawn Schulte, Nathan Hauge, Ashley Scott, Chris Henry, Mark Scott, Sherry Herrmann, Tasha Skidmore, Melissa Thinner Hilbrands, Jason Spyksma, Jeff Hinsch, Sara Stientjes, Valerie Hoekstra, Christina Surma, Joe Hoogeveen, Kay Van Veldhuizen, Keri Hoppe, Lari Vande Kop, Holly Johnson, Lonette Vande Kop, Todd Kahl, Michael Venenga, Todd Kelderman, Jodi Vogl, Lissa Kix, Marla Vogl, Michelle Klinkenborg, Chris Warntjes, Wade Kooiker, Nolan Woodrow, Robert Central Lyon Class List 1991 Andy, Anderson Mantle, Mark Lewis, Anderson Matson, Sherry Rachel, Baatz McDonald, Chad Lyle, Bauer Miller, Bobby Darcy, Berg Miller, Penny Paul, Berg Moser, Jason Shane, Boeve Mowry, Lisa Borman, Zachary Mulder, Daniel Breuker, Theodore Olsen, Lisa Christians, Amy Popkes, Wade De Yong, Jana Rath, Todd Delfs, Rodney Rau, Gary Ellsworth, Jason Roths, June Fegan, Carrie Schillings, Roth Gardner, Sara Schubert, Traci Gingras, Cindy Scott, Chuck Goette, Holly Solheim, Bill Grafing, Jennifer Steenblock, Amy Grafing, Robin Stettnichs, -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

STUDY GUIDE The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Balak NUMBERS 22:2-25:9 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Parashat Balak Study Guide Themes Theme 1: The Seer Balaam—Have Vision Will Travel Theme 2: It’s a Slippery Slope—the Dangers of Foreign Women INTRODUCTION n Parashat Balak the Israelites are camped on the plains of Moab, ready Ito enter Canaan. In the midst of their final preparations to enter the land God promised to their ancestors, yet another obstacle emerges. Balak, king of Moab, grows concerned about the fierce reputation of the Israelites, which he observed in the Israelites’ encounter with the Amorites (Numbers 21:21–32). Balak’s subjects worry that the Israelites, due to their large numbers, will devour the resources of Moab. In response, Balak hires a well-known seer named Balaam to curse the Israelites, thus reflecting the widely held belief in the ancient world that putting a curse on someone was an effective means of subduing an enemy. The standoff between the powers of the God of Israel and those of a foreign seer proves to be no contest. Even Balaam’s talking female donkey, who represents the biblical ideal of wisdom, recognizes the efficacy of God’s power—unlike her human master, the professional seer. Although hired to curse the Israelites, Balaam ends up blessing them instead. In a series of four oracles, Balaam ultimately does the opposite of what Balak desires and establishes that the power of Israel’s God is greater than even the most skilled human seers. -

The Zeal of Pinchas (Phinehas)

Kehilat Kol Simcha July 27, 2019 Gainesville, Florida Shabbat Teaching The Zeal of Pinchas (Phinehas) 10 Then Adonai spoke to Moses saying, 11 “Phinehas son of Eleazar son of Aaron the kohen has turned away My anger from Bnei-Yisrael because he was very zealous for Me among them, so that I did not put an end to Bnei-Yisrael in My zeal. 12 So now say: See, I am making with him a covenant of shalom! 13 It will be for him and his descendants a cove- nant of an everlasting priesthood—because he was zealous for his God and atoned for Bnei-Yisrael” (Nu. 25:10-13). It is advantageous to read/review the context of the beginning Parashat Pinchas when the Torah celebrates Pinchas’ zeal. Israel falls prey to the sin of immorality and idolatry. In last week’s Torah Reading (Balak) the gentile prophet Balaam was unable to curse Israel even though Moabite King Balak offered him a great reward. After blessing Israel in Numbers 24 Balaam and Balak depart from each other without Balaam getting any reward: “25 Then Balaam got up and went and returned to his own place, and Balak went on his way” (Numbers 24:25). That was not the end of Balaam’s influence and evil doings. Yeshua elucidates on the doctrine/teaching of Balaam to the Messianic Congregation at Pergamum: “14 But I have a few things against you. You have some there who hold to the teaching of Balaam, who was teaching Balak to put a stumbling block before Bnei-Yisrael, to eat food sacrificed to idols and to commit sexual immorality” (Rev. -

Matot-Masei – July 10, 2021

Stollen Moments – Matot-Masei – July 10, 2021 PARASHA SUMMARY FROM WWW. REFORMJUDAISM.ORG • Moses explains to the Israelites the laws concerning vows made by men and women. (30:2—17) • Israel wages war against the Midianites. (31:1—18) • The laws regarding the spoils of war are outlined. (31:19—54) • The tribes of Reuben and Gad are granted permission to stay on the east bank of the Jordan River. (32:1—42) • The itinerary of the Israelites through the wilderness from Egypt to Jordan is delineated. (33:1-49) • Moses tells Israel to remove the current inhabitants of the land that God will give them and to destroy their gods. (33:50-56) • The boundaries of the Land of Israel are defined, along with those of the Levitical cities and the cities of refuge. (34:1-35:15) • God makes a precise distinction between murder and manslaughter. (35:16-34) • The laws of inheritance as they apply to Israelite women are delineated. (36:1-13) Numbers Chapter 31 1 The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, 2 "Avenge the Israelite people on the Midianites; then you shall be gathered to your kin." 3 Moses spoke to the people, saying, "Let men be picked out from among you for a campaign, and let them fall upon Midian to wreak the Lord's vengeance on Midian. 4 You shall dispatch on the campaign a thousand from every one of the tribes of Israel." 5 So a thousand from each tribe were furnished from the divisions of Israel, twelve thousand picked for the campaign. -

The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 40 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2001 Joseph Smith's Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation Kent P. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Kent P. (2001) "Joseph Smith's Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 40 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackson: Joseph Smith's Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the B joseph smithssmithes Cooperscooperstowntown bible the historical context ofthe bible used in the joseph smith translation kent P jackson in october 1829 joseph smith and oliver cowdery obtained the bible that was later used in the preparation of joseph smiths new translation of the holy scriptures it was a quarto size king james translation published in 1828 by the H and E phinney company of Cooperscooperstowntown new york 1 the prophet and his scribe likely did not know that their new book would one day become an important artifact of the restoration and they proba- bly also never considered the position in -

Characters and Events of Roman History, from Csar to Nero

LIBRARY UMtVEMSITY Of CAUFORNIA 1 SANOtEGO J Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/characterseventsOOferriala ^- uJ^ THE GREATNESS AND DECLINE OF ROME BY GUGLIELMO FERRERO Authorited Translation 5 vols. 8vo. Each |2. 50 net Vol. I.—The Empire Builders Vol. II.—Julius Caesar Vol. III. —The Fall of an Aristocracy Vol. IV.—Rome and Egypt Vol. V. —The Republic of Augustus CHARACTERS AND EVENTS OF ROMAN HISTORY From Caesar to Nero (60 B.C.-70 A.D.) AMthorited Translation by Frances Lance Ftrrero 8vo. \e^i6i Characters and Events of Roman History From Caesar to Nero iTbe XoweU Xectuces of 1908 By Guglielmo Ferrero, Litt. D. Author of "The Greatness and Decline of Rome," etc. Translated by Frances Lance Ferrero G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London ^be ftniclierbocher press 1909 Copyright, iqoq BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Published, May, 1909 Reprinted, October, 1909 «be fmicketbociiec fhress, «ew Vwk PREFACE IN the spring of 1906, the College de France in- * vited me to deliver, during November of that year, a course of lectures on Roman history. I accepted, giving a r6sum6, in eight lectures, of the history of the government of Augustus from the end of the civil wars to his death ; that is, a r6sum6 of the matter contained in the fourth and fifth volumes of the English edition of my work. The Greatness and Decline of Rome. Following these lectures came a request from M. Emilio Mitre, Editor of the chief newspaper of the Argentine Republic, the Nacion, and one from the Academia Brazileira de Lettras of Rio de Janeiro, to deliver a course of lectures in the Argentine and Brazilian capitals. -

The Anteby Family History and Heritage As Well As in Hebrew

The Anteby Family History and Heritage By Dr Elioz Antebi Hefer (Surname has several relevant equivalents: Antebi, Anteby Antibi, Entebi Enteby etc. (…etc ענתבי ענתיבי עינתיבי : As well as in Hebrew About the family name The Antebi's family roots go back to the expulsion from Spain in 1492. Some family elders claimed that we belong to a group of Jews who stayed in the area since biblical times (called "Musta'arevin" ) but neither of the assumption can be proved. Members of the family settled in a small town Ein Tab which is situated in the Diar Bakir Turkish district, the meaning of its Arabic name is "the Good Fountain". After the Turk have concurred the area they have added a Turkish prefix to the name Eintab : "Gazi" which means in Turkey "the conqueror". Thus the modern name of the city is today Gaziantep . After immigrating from Ein-Tab to Aleppo the family was named Antebi (= derived from Ein Tab) , and the original Spanish (or Musta'arev) name of the family was forgotten. Many members of this family were famous Torah scholars, rabbis and leaders of the Jewish community in Aleppo Damascus Egypt and Eretz Israel. Finding the roots - conducting an historical inquiry back in time My "return travel" back in time through 11 generations of ancestors until the small historical town "Ein Tab" has been conducted for thirty years. I have collected along that way shreds of information left by family elders : Memoires and autobiographies , childhood stories , past newspaper articles collected carefully regarding different family members , photographs (though those 1 were occasionally rare) Archive data, History books and research articles written about historical events in which the family was involved . -

"Moses Wrote His Book and the Portion of Balaam" (Tb Bava Batra 14B)

"MOSES WROTE HIS BOOK AND THE PORTION OF BALAAM" (TB BAVA BATRA 14B) SHUBERT SPERO The story of Balaam in the Book of Numbers (Chapters 22-24) has over time elicited a number of serious questions both structural, pertaining to the story as a whole, its authorship and place in the canon, and internal, pertain- ing to the plot and its characters. Its location in the Book of Numbers seems appropriate as one of the events which occurred on the east side of the Jor- dan. However, it is told completely from the vantage point of Balak, King of Moab: what he thought, how he invited a sorcerer from Mesopotamia to curse Israel, what God told Balaam, and how Balaam responded. The ques- tion is: how did this information get to Moses, since he was not at all in- volved in the event? There is no indication in the text that this was revealed to him by means of prophecy. I believe that these questions prompted the Rabbis in the above title to insist that it was, nevertheless, Moses who com- posed the Portion of Balaam. I will return to this later. In terms of the story itself, the main questions have been: 1) Why does God initially forbid Balaam to accept Balak's invitation and, when the delegation returns with a better offer, why does God tells him to go with them? 2) Why is Balak so insistent on urging Balaam to try again and again, when the sorcerer has repeated over and over that God, not he, is in control? 3) How are we to understand the inclusion of a story about a pagan sorcerer and a talking donkey in the Torah? But perhaps the most interesting question of all centers around the character and personality of Balaam who, the Rabbis decided, was a rasha – "wicked" and dissolute. -

Dier 'Alla Inscription Confirming the Existence of Balaam Son of Beor

Dier 'Alla Inscription Confirming the existence of Balaam son of Beor Approximately 5 miles east of the Jordan River and .7 miles north of the Jabbok River lies the ancient ruins of Deir 'Alla in Jordan. Deir 'Alla suffered widespread destruction around the 13th-12th century B.C. and was rebuilt and continuously inhabited until the 5th century B.C. when it was destroyed by an earthquake. In March 1967, a team of archeologists led by Dr. Henk Franken discovered lettering on 119 fragments of plaster littering the floor of a large Bronze Age sanctuary in the earthquake's debris field. Painted in red and black ink, the recovered fragments formed an inscription that was written in Aramaic. In their reconstruction, archeologists believe that the inscription was in a long column with more than 50 lines. Despite the damaged and fragmentary nature of the inscription, archeologists have reconstructed enough to see that it mentions "Balaam son of Boer" three times in the first four lines, and it tells of a prophecy by Balaam foretelling of the destruction of his people. The best Dier 'Alla Inscription reconstruction can be seen at the end of this article. Carbon dating places the Dier 'Alla Inscription in the period of 840-760 B.C. Balaam of Beor existed some 600 years or so earlier. Scholars, aware of this discrepancy, note that the inscription refers to the "Book of Balaam" which indicates the presence of a pre-existing manuscript or scroll; thus, the date of the material is certainly earlier. Other evidence attesting to the historical reality of Balaam of Beor is the geographical proximity of the Dier 'Alla Inscription to the biblical accounts of Balaam of Beor.