Threatened Species Strategy Year 3 Scorecard – Regent Honeyeater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

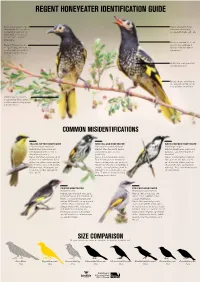

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands

Conservation Management Zones of Australia South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Yanga or Murrumbidgee Valley National Park – Paul Childs/OEH Page 4: River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) – Allan Fox Page 10: Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) – Trent Browning Page 16: Gunbower Creek – Arthur Mostead Page 19: Eastern Grey -

Regent Honeyeater Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

#41 This Action Statement was first published in 1993 and remains current. This Regent Honeyeater version has been prepared for web publication. It Xanthomyza phrygia retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Regent Honeyeater (Xanthomyza phrygia) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, (Illustration by John Las Gourgues) East Melbourne, distributed within about 300 km of the Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution The Regent Honeyeater (Xanthomyza eastern Australian coast from about 100 km This publication may be of phrygia Shaw 1794) is a specialised, north of Brisbane to Adelaide. However, it is assistance to you but the medium-size honeyeater (Family no longer found in South Australia (Franklin State of Victoria and its Meliphagidae) inhabiting drier open forests & Menkhorst 1988) or western Victoria employees do not guarantee and woodlands in south-eastern Australia. (Franklin et al. 1989). Further, population that the publication is Adults weigh 41 to 46 g. Plumage is dispersion within this distribution is now without flaw of any kind or predominantly black with bright yellow patchy. The species is highly mobile, but is wholly appropriate for little information is available on movement your particular purposes edges to tail and wing feathers. Body patterns. and therefore disclaims all feathers, except for the head and neck, are liability for any error, loss broadly edged in pale yellow or white In Victoria, Regent Honeyeaters occur or other consequence which (Longmore 1991). -

REGENT HONEYEATER Anthochaera Phrygia Critically Endangered

Zoos Victoria’s Fighting Extinction Species REGENT HONEYEATER Anthochaera phrygia Critically Endangered Fewer than 400 Regent Honeyeaters are A successful captive-breeding and release thought to occur in the wild, the result of program, led by Taronga Conservation ongoing declines over the past 30 years. Society Australia, Birdlife Australia and the Population modelling indicates a higher than Victorian Department of Environment, Land, 50% probability of extinction during the next Water and Planning has been underway 20 years, placing it among Australia’s most since 1995 to bolster the wild population. imperilled birds. The ongoing declines of Regent Zoos Victoria will increase its support for Honeyeaters in the wild indicate that it is time this species by increasing the holding and to expand the captive program to provide a breeding capacity of Regent Honeyeaters greater level of insurance against extinction. across the captive breeding program. Zoos Victoria is committed to Fighting Extinction We are focused on working with partners to secure the survival of our priority species before it is too late. The ongoing declines of Regent Honeyeaters in the wild indicate that it is time to expand the captive program to provide a greater level of insurance against extinction. Halting the declining trend for this iconic honeyeater requires the dedicated efforts of many partners. Strong foundations are in place, but it will take time to increase the extent and quality of Regent Honeyeater habitat. Importantly, critical support measures are in place, including field surveys, while efforts to mitigate threats in the wild take effect. KEY PROGRAM OBJECTIVES A successful captive-breeding and release • Increase the size of the insurance program, led by Taronga Conservation population. -

Regent Honeyeater: Icon Threatened Species

Regent Honeyeater: icon threatened species Scientific name: Xanthomyza phrygia Other common names: Turkey Bird, Embroidered Honeyeater Conservation status: Endangered in NSW and Australia How do I recognise it? blakelyi) and River Oak (Casuarina cunninghamiana). The Regent Honeyeater is a medium sized bird (about the size of a starling). What does it eat? A spectacularly marked bird, it has a black beak, black head and a bare Regent Honeyeaters principally feed cream to pinkish patch of warty skin on: around their eye. The back and • Nectar of eucalypts (see those breast appear scaly (pale lemon and listed above). black), while the wings and tail are • Nectar and fruit of mistle- edged with bright yellow. Males and toes including; Needle-leaf females are similarly coloured. Regent Honeyeater (Photo: N Lazarus) Mistletoe (Amyema cambagei), A. miquelii It is often found high in the tree the western slopes, especially box- Box Mistletoe ( ) and A. pendu- canopy of flowering eucalypts, and ironbark and riparian woodlands. Drooping Mistletoe ( lum often occurs with Lorikeets and Key habitat trees include: Mugga ) Friarbirds. Ironbark (Eucalyptus sideroxylon), • Sugary exudates from insects Yellow Box (E. melliodora), White when nectar is scarce, and Within the Border Rivers Gwydir Box (E. albens), Grey Box (E. • Insects themselves during the Catchment, the only similarly sized moluccana), Blakely’s Red Gum (E. breeding season. and coloured bird is the Painted Honeyeater. The Painted Honeyeater Mature Grassy Box Woodlands are important Regent Honeyeater habitat (Photo: W Hawes) is distinguished by its solid black back, white throat and breast, lack of a warty patch about the eye and pink beak. -

Loss of Vocal Culture and Fitness Costs in a Critically Endangered Songbird

Loss of vocal culture and fitness costs in a royalsocietypublishing.org/journal/rspb critically endangered songbird Ross Crates1, Naomi Langmore2, Louis Ranjard2, Dejan Stojanovic1, Laura Rayner1, Dean Ingwersen3 and Robert Heinsohn1 Research 1Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Linnaeus Way, Acton, Canberra 2601, Australia Cite this article: Crates R, Langmore N, 2Research School of Biology, Australian National University, 46 Sullivan’s Creek Rd, Acton, Ranjard L, Stojanovic D, Rayner L, Ingwersen Canberra 2601, Australia 3BirdLife Australia, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia D, Heinsohn R. 2021 Loss of vocal culture and fitness costs in a critically endangered RC, 0000-0002-7660-309X; NL, 0000-0003-3368-6697; DS, 0000-0002-1176-3244; RH, 0000-0002-2514-9448 songbird. Proc. R. Soc. B 288: 20210225. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0225 Cultures in humans and other species are maintained through interactions among conspecifics. Declines in population density could be exacerbated by culture loss, thereby linking culture to conservation. We combined his- torical recordings, citizen science and breeding data to assess the impact Received: 28 January 2021 of severe population decline on song culture, song complexity and individ- Accepted: 19 February 2021 ual fitness in critically endangered regent honeyeaters (Anthochaera phrygia). Song production in the remaining wild males varied dramatically, with 27% singing songs that differed from the regional cultural norm. Twelve per cent of males, occurring in areas of particularly low population density, comple- tely failed to sing any species-specific songs and instead sang other species’ Subject Category: songs. Atypical song production was associated with reduced individual fit- Global change and conservation ness, as males singing atypical songs were less likely to pair or nest than males that sang the regional cultural norm. -

Regent Honeyeater Disease Risk Analysis

Regent Honeyeater Disease Risk Analysis February, 2015 1 Acknowledgements The following individuals and organisations contributed to the compilation of information on which this risk analysis is based: Larry Vogelnest, Michael Shiels, Paul Andrew (Taronga Conservation Society Australia), Dean Ingwersen (BirdLife Australia), Karrie Rose (Australian Registry of Wildlife Health) and Tiggy Grillo (Wildlife Health Australia). Contributors to a workshop held on 15-16 October 2014 to elicit expert opinion and discussion of issues relevant to this DRA included, in addition to the above, Glen Johnson, Peter Menkhorst (Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning), Peter Christie, David Geering (Office of Environment and Heritage, New South Wales), Judith Gillespie, Frances Hulst, Cheryl Sangster (Taronga Conservation Society Australia), Jan Slapeta (University of Sydney), Rupert Baker (Zoos Victoria) and Andrea Reiss (Zoo and Aquarium Association). The generosity of workshop participants and their affiliated organisations in sharing their knowledge and expertise and in providing the time and resources to attend this workshop is greatly appreciated Claudia Carraro, John Ewen and Stefano Canessa donated their time and expertise free of charge as a contribution to the Regent Honeyeater Recovery Program. This work was further sponsored by the IUCN-SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (Australasia), Auckland Zoo, Taronga Conservation Society Australia, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (Victoria), BirdLife Australia, and the Zoological Society of London. Cover photo: Regent Honeyeater, Anthochaera phrygia by Dean Ingwersen. © Copyright 2014 CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. -

Canberra Bird Notes Is Published Quarterly by the Canberra Ornithologists Group Inc

ISSN 0314-8211 CANBERRA Volume 13 Number 2 BIRD June 1988 NOTES Registered by Australia Post - publication No NBH 0255 NOTES ON CURRAWONG - SPARROWHAWK INTERACTIONS E.C. (Slim) Metcalf, 11 Peel St, O'CONNOR ACT 2601 Received: 10 February 1988 In a previous paper (R. & E.C. Metcalf 1986) I reported that the Pied Currawong Strepera graculina was the instigator and receiver of most of the physical harassment at the nest of a pair of Collared Sparrowhawks Accipiter cirrocephalus. Here I discuss this aspect in greater detail. As is clear from observation and many published reports, the Pied Currawong is a versatile feeder but takes a considerable number of small birds, mainly nestlings and fledglings. The Collared Sparrowhawk by contrast feeds almost entirely on small flying birds (Czechura, Debus and Mooney 1987). Thus whilst there is a small ecological overlap it appears that the Sparrowhawk is of little threat to the Currawong but being so small, it probably suffers by virtue of the latter's antagonism towards hawks, attempts at thieving prey and presumably risk of predation on young chicks. J. & P. Olsen have an adult female Sparrowhawk that is missing an eye due to attack by Currawongs. Pied Currawongs appear to be capable of 'urban drift'. It has been suggested that in 1987/8 the Currawongs' previously marked summer migration to the ranges to breed has just about ceased. Certainly there were much greater numbers of these birds in Canberra seeking nest sites than in prior years. This may be having significant effect on the breeding success of many other birds. -

THE Victorian Naturalist

THE Victorian Naturalist THE JOURNAL AND MAGAZINE of the FIELD NATURALISTS' CLUB OF VICTORIA VOL. 61 MAY, 1944. TO' APRIL, 1945 Hon. Editor: A. H. CHISHOLM, F.R.Z.S. The Author of each Article is responsible for the facts and opinions recorded Melbourne : Brown, Prior, Anderson Pty. Ltd., 430 Little Bourke Street 1945 Boo. Trmumt Mr, S. S, tJM^t99i6dck^S&ti^iRmAW(i^Q:, jfefira - Hoi* UJwartim: llr, p. *EJ CT£J^Woai)H 85^Gr&T^^^GroVp,^^^^ Hcil AflfiisU'iU LOrffttba:-"Mat/:*. SUfikl^T ChaiftsMbtSt MSta^SSE — — — • The Victorian Naturalist VoL 61.—No. i ._ May 4, 1944 No. 725 PROCEEDINGS The monthly meeting of the Club was held on Monday, April 10, 1944, at the Royal Society's Hail. Mr, Tvo C Ilammet, vice-presideit, presided in the absence of the president, and some 80 members and friends attended. Reports of excursions were given a* follows; Queen's Park, Miss Wigan (who reported noting five species of ducks, including die Musk Duck, as well as Moor liens, Grebes, Coots, etc.) ; Willis. Seaholme, Mr. J. H. The following were elected as ordinaiy members: Mr. and Mrs. .Burgess, Mrs. C\ W. Connery, Miss Nellie Stewart, Mr. Albert P. Dunn; as country members; Mr. A. Teesc and Mr. S* C- Nicul; and as associate member: Miss Valda Ralcy, NATURE PROBLEMS Hie subject for the evening was "Quest Night/* wherein members were invited to submit queries that: were passed by the Chair for discussion and reply by other members. Following are the items (with rep/tes) that came before the meeting; BOTANICAL QUESTIONS 1. -

Regent Honeyeater– Profile

APPENDIX 5: THREATENED FAUNA SPECIES PROFILES The following profiles are sourced from the Department of Environment and Climate Change. Regent Honeyeater – profile Scientific name: Xanthomyza phrygia Conservation status in NSW: Endangered National conservation status: Endangered Description The Regent Honeyeater is a striking and distinctive, medium-sized, black and yellow honeyeater with a sturdy, curved bill. Adults weigh 35 - 50 grams, are 20 - 24 cm long and have a wings-pan of 30 cm. Its head, neck, throat, upper breast and bill are black and the back and lower breast are pale lemon in colour with a black scalloped pattern. Its flight and tail feathers are edged with bright yellow. There is a characteristic patch of dark pink or cream-coloured facial-skin around the eye. Sexes are similar, though males are larger, darker and have larger patch of bare facial-skin. The call is a soft metallic bell- like song; birds are most vocal in non-breeding season. Distribution The Regent Honeyeater mainly inhabits temperate woodlands and open forests of the inland slopes of south-east Australia. Birds are also found in drier coastal woodlands and forests in some years. Once recorded between Adelaide and the central coast of Queensland, its range has contracted dramatically in the last 30 years to between northeastern Victoria and south- eastern Queensland. There are only three known key breeding regions remaining: north-east Victoria (Chiltern-Albury), and in NSW at Capertee Valley and the Bundarra-Barraba region. In NSW the distribution is very patchy and mainly confined to the two main breeding areas and surrounding fragmented woodlands. -

Regent Honeyeater) Conservation Advice 2019

Australian Capital Territory Nature Conservation (Regent Honeyeater) Conservation Advice 2019 Notifiable instrument NI2019–252 made under the Nature Conservation Act 2014, s 90C (Conservation advice) 1 Name of instrument This instrument is the Nature Conservation (Regent Honeyeater) Conservation Advice 2019. 2 Commencement This instrument commences on the day after its notification day. 3 Conservation advice for the Regent Honeyeater Schedule 1 sets out the conservation advice for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia). Arthur Georges Chair, Scientific Committee 1 May 2019 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au Schedule 1 (see s 3) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au CONSERVATION ADVICE REGENT HONEYEATER Anthochaera phrygia CONSERVATION STATUS The Regent Honeyeater Anthochaera phrygia (Shaw, 1794) is recognised as threatened in the following jurisdictions: International Critically Endangered, International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List National Critically Endangered, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Critically Endangered, Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010 ACT Critically Endangered, Nature Conservation Act 2014 NSW Critically Endangered, Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 VIC Threatened, Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Critically Endangered, Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna 2013 QLD Endangered, Nature Conservation Act 1992 SA Endangered, National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 ELIGIBILITY The Regent Honeyeater is listed as Critically Endangered in the ACT Threatened Native Species List under IUCN Criterion A —A2a. The factors that make it eligible include a very severe population decline (≥80%) over the past three generations (24 years) and the decline and its cause have not ceased (Department of the Environment (DoE) 2015).